Here follows a blizzard of names, and I could have included more, if I'd used the entire rateyourmusic list for the year. But it gives you some idea of the richness and vitality of jazz in mid-decade.

Surely the biggest news from the Prestige label in 1956 was the wrapping up of the

Miles Davis Contractual Marathon. He recorded fourteen songs in May, then twelve more in October, then Miles was off into the future, and one of the most storied careers in jazz, although Prestige would continue releasing albums from these sessions into 1961. The cuts were all first takes, and if Miles was rushing through them...well, he wasn't. The four albums that came out of the Contractual Marathon sessions, with John Coltrane and what became known as the First Great Quintet, remain some of Miles's most beloved work.

And they actually weren't all he did for Prestige that year. He led another quintet, with Sonny Rollins and Tommy Flanagan, in March.

And he left another legacy with Prestige, namely, his rhythm section. Bob Weinstock signed Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones to their own contract, and the trio, generally with Art Taylor on drums, would record nearly 30 albums for the label under Garland's name, and a bunch more backing up others.

Prestige was amassing one of the great rosters of rhythm section men in jazz history. In 1956 alone,

Garland would play seven recording sessions,

Paul Chambers ten, and

Philly Joe Jones ten. And that was just the start of it.

Mal Waldron appeared on six sessions,

Doug Watkins on ten,

Art Taylor on 14. So some cats were getting steady work, if they weren't exactly getting rich off it.

And others became very familiar with Hackensack. The summer of 1956 saw the Fridays with Rudy, as every weekend was preceded by one or even two Friday recording sessions. All in all, 48 sessions went down under the Prestige auspices, 41 of them in Rudy Van Gelder's studio

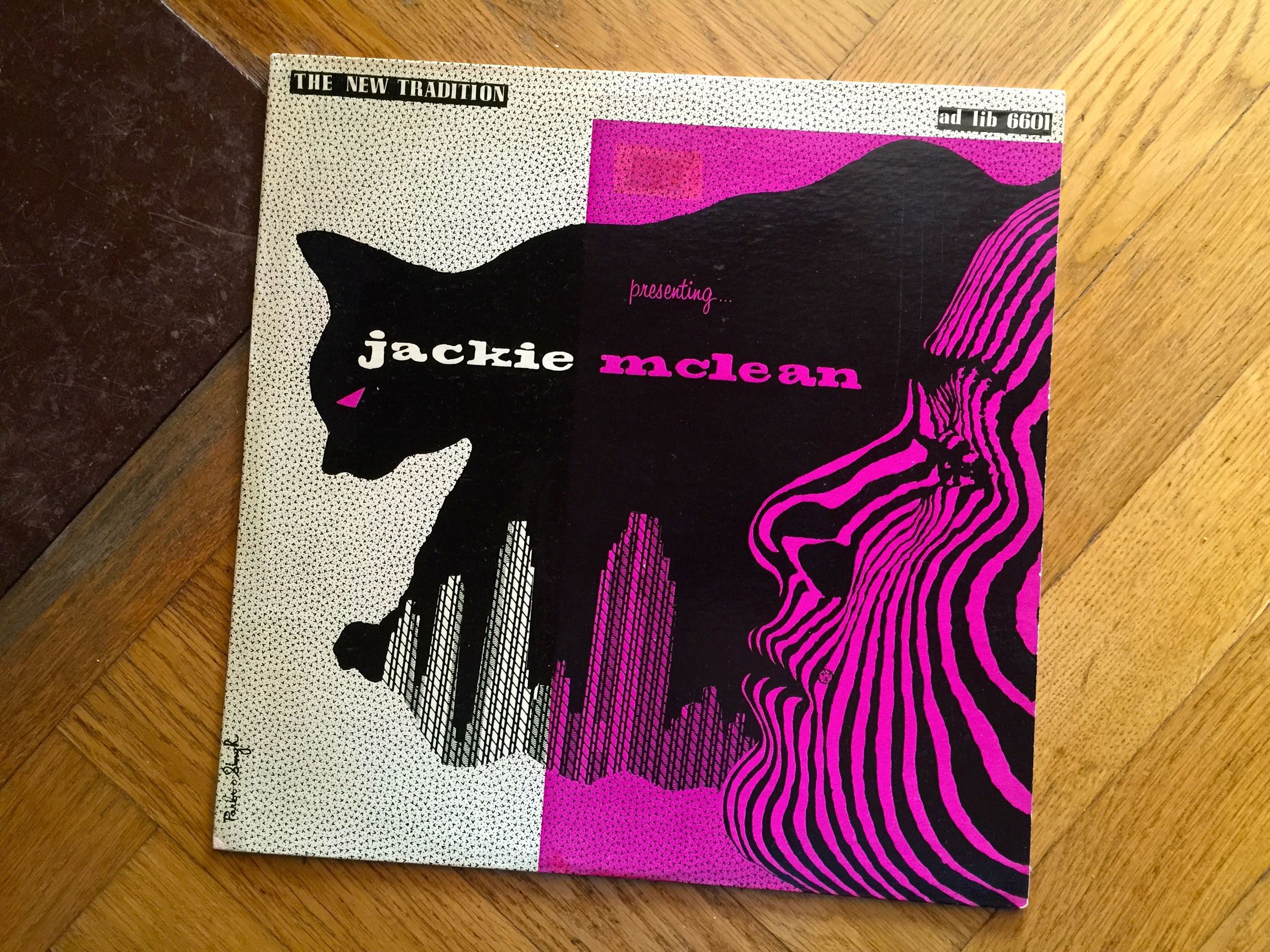

Jackie McLean recorded five sessions as leader, four more as sideman.

Sonny Rollins did five as leader, one with Miles Davis. One of these was the only recording session to bring Rollins and John Coltrane together, on the epic "Tenor Madness." Like Miles, he moved on from Prestige after 1956.

Donald Byrd was around a lot, with eight sessions as a sideman, one as a co-leader with Phil Woods, and two as a member of the Prestige All-Stars (one of these would be re-released as

2 Trumpets, leader credit shared by Byrd and Art Farmer).

Hank Mobley also did two Prestige All-Stars sessions, three more as sideman and two as leader. Both Byrd and Mobley were to move over to Blue Note, where Mobley would stay for the rest of his recording career, whereas Byrd would eventually move on to new sounds with new labels.

John Coltrane made the two Contractual Marathon sessions, and also played with Elmo Hope, Sonny Rollins, the Prestige All-Stars and Tadd Dameron.

Some were passing through.

Jon Eardley made his fourth and last record for Prestige in January, then faded into obscurity for 20 years until he started recording again in Europe.

George Wallington led a group with Donald Byrd and Phil Woods. He would make a few more records over the next year (one for New Jazz) before retiring to join the family's air conditioning business; it would be 30 years before he recorded again.

Tadd Dameron recorded far too little. His lasting reputation and legacy in jazz circles is testimony to how much we would have liked to get more of him, how lucky we were to get what we did. He went into the studio twice for Prestige in 1956, once with an octet, once with a quartet featuring John Coltrane. He would only make one more record after this, for Riverside in 1962.

Bennie Green would make his last Prestige albums during the year, as would

Elmo Hope, with one album as leader and two as sideman.

Gil Melle was actually quite active, cutting four sessions for Prestige in 1956, but he was shortly to take off for Hollywood and a career as composer of electronica and film scores.

Prestige recorded a few singers in 1956.

Earl Coleman actually did go on recording, off and on, into the 1980s, but his career never really took off. At his best, he was very good.

Barbara Lea's sessions for Prestige won her

DownBeat's Critics' Award as Best New Singer of 1956, but she left singing for acting, to return to it years later.

Blind Willie McTell was recorded in Atlanta in 1956, and his songs were later released on Prestige subsidiary Bluesville.

So, a good year for Bob Weinstock's label, as he continued to be at the hot epicenter of what was happening in jazz,

Clifford Brown appeared on one Prestige album along with Max Roach and Sonny Rollins -- it was the same group that had made such great records for EmArcy, but here under Rollins's name as leader. And Brown was to die that same year in a tragic auto accident that also claimed pianist Richie Powell.

Also departing the scene in 1956 were Art Tatum, Tommy Dorsey and Frankie Trumbauer.

Variety listed the top-selling jazz albums of the year:

Ella and Louis, Verve

Stan Kenton--

Cuban Fire, Capitol

Jai and Kai plus 6, Columbia

Ella Fitzgerald sings the Cole Porter Songbook, Verve

Errol Garner--

Concert by the Sea, Columbia

Kenton in Hi-Fi, Capitol

Chris Connor--

He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not, Atlantic

Modern Jazz Quartet--

Fontessa, Atlantic

Ella and Louis is undoubtedly still a jazz best-seller. So, probably, are

Concert by the Sea, the MJQ album, and Ella singing Cole Porter, the first of her

Songbook albums.

Other major releases for the year: Monk's

Brilliant Corners, Mingus's

Pithecanthropus Erectus, Rollins's

Saxophone Colossus, Quincy Jones's

This is How I Feel About Jazz, and of course, the obligation to Prestige having been filled, Miles's

Round About Midnight for Columbia

Live releases from the Newport Jazz Festival included Dave Brubeck with Jay and Kai, and, most significantly, Duke Ellington. The classic

Ellington at Newport was actually not the Duke's only live album from the festival: Check out the lesser-known

Duke Ellington and the Buck Clayton All-Stars at Newport.

Metronome was

DownBeat's chief competitor as a jazz magazine in the 40s and 50s, though it had actually been around since 1881, originally focusing on marching band music. Periodically, it would issue a Metronome Poll Winners LP, featuring a jam session of as many of the winners or near-winners as the staff (which included Leonard Feather) could get together. 1956 was their last dance, a 21-minute version of Charlie Parker's "Billie's Bounce," with solos by Thad Jones (trumpet), Lee Konitz (alto), Al Cohn and Zoot Sims (tenor), Tony Scott (clarinet), Serge Chaloff (baritone), Eddie Bert (trombone), Teddy Charles (vibes), Tal Farlow (guitar, Billy Taylor (piano), Charles Mingus (bass) and Art Blakey (drums).

Metronome would cease publication in 1961.

A TV series hosted by Bobby Troup and called

Stars of Jazz debuted on KABC-TV in Los Angeles. Its first show featured the Stan Getz Quartet and Kid Ory and his Creole Jazz Band

Here is my annual gripe about the crime against culture of not preserving all of

DownBeat on digital archive. And as I write this, one cannot even access the readers' and critics' polls. Here's hoping that's a temporary glitch.

But here is the wonderfully bizarre RateYourMusic poll for the year, just including the jazz selections (#1 is Glenn Gould's

Goldberg Variations). Don't forget these are 1956 releases, not recordings, which explains the presence of older sessions like the MJQ's Django.

2

Ellington at Newport

3

Pithecanthropus Erectus

The Charlie Mingus Jazz Workshop

4

Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Song Book

5

Lady Sings the Blues

Billie Holiday

6

Ella and Louis

9

Songs for Swingin' Lovers!

Frank Sinatra

11

Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Rodgers and Hart Song Book

12

Clifford Brown & Max Roach At Basin Street

14

The Jazz Messengers at the Cafe Bohemia, Volume 1

15

The Jazz Messengers

16

Sonny Rollins Plus 4

17

Tenor Madness

Sonny Rollins Quartet

20

Mingus at the Bohemia

21

Jazz Giant

Bud Powell

22

Concert by the Sea

23

Lennie Tristano

24

The Jazz Messengers at the Cafe Bohemia, Volume 2

26

Fontessa

28

Stan Getz Plays

33

Blue Serge

Serge Chaloff

34

Django

The Modern Jazz Quartet

35

Moondog

36

Moonlight in Vermont

Johnny Smith featuring Stan Getz

37

Jazz at Oberlin

The Dave Brubeck Quartet

38

The Unique Thelonious Monk

40

Here Is Phineas: The Piano Artistry of Phineas Newborn

42

Herbie Nichols Trio

43

Count Basie Swings - Joe Williams Sings

45

Whims of Chambers

Paul Chambers Sextet

46

The Boss of the Blues: Joe Turner Sings Kansas City Jazz

47

Ambassador Satch

Louis Armstrong

48

The Genius of Bud Powell

49

Russ Freeman / Chet Baker Quartet

50

Blossom Dearie

51

Miles

The New Miles Davis Quintet

52

Hi Fidelity Jam Session

Gene Ammons

54

Chris Connor

56

Modern Jazz Performances of Songs From My Fair Lady

Shelly Manne & His Friends

57

Jazz Workshop

George Russell

58

Jazz Immortal

Clifford Brown

59

Quintet / Sextet

Miles Davis and Milt Jackson

60

Lonely Girl

Julie London

61

Lights Out!

The Jackie McLean Quintet with Donald Byrd and Elmo Hope

62

Grand Encounter: 2° East / 3° West

John Lewis

63

Chamber Music of the New Jazz

Ahmad Jamal

64

Chet Baker Quartet Vol. 2

66

Work Time

Sonny Rollins

69

The Modern Jazz Sextet (Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Stitt, John Lewis, Percy Heath, Skeeter Best, Charlie Persip)

73

The Jazz Giants '56

Lester Young, Teddy Wilson, Roy Eldridge, Vic Dickenson, Jo Jones, Freddie Green & Gene Ramey

75

The Kenny Drew Trio

76

Kenton in Hi-Fi

77

Collectors' Items

Miles Davis

78

The Oscar Peterson Trio at the Stratford Shakespearean Festival

79

Calendar Girl

Julie London

80

Sarah Vaughan in the Land of Hi-Fi

I always get carried away with this list because it's so exhaustive. It goes on through #1200. Anyway, other jazz artists included farther down the list are Kenny Burrell, Rosemary Clooney, June Christy, Mel Tormé With Marty Paich, Jimmy Smith, Harry Edison, Gene Krupa, Tito Puente, Jimmy Giuffre, Tal Farlow, Teddy Charles, Elmo Hope, Chico Hamilton, the High Society soundtrack, Thad Jones, Gene Ammons, Cannonball Adderley, Hampton Hawes, Art Tatum, Curtis Counce, Sonny Criss, Warne Marsh, Gil Mellé, Dexter Gordon, Herb Ellis, Vince Guaraldi, Art Pepper, Art Farmer, Dinah Washington, George Shearing, Tadd Dameron, Phil Woods, Alain Goraguer, Jon Eardley, Betty Carter & Ray Bryant, Maxine Sullivan, Shelly Manne, Gene Quill, Al Cohn & Zoot Sims, Coleman Hawkins with Billy Byers, Kid Ory, Buddy Rich, Cal Tjader, Shorty Rogers, Tommy Dorsey, Gerry Mulligan, James Moody, Jimmy Cleveland, Betty Roché, Lee Konitz, Kenny Clarke, Jackie McLean, Bill Perkins, Carl Perkins, Randy Weston, Toni Harper, Carmen McRae, Meade Lux Lewis, Herbie Mann, Billy Bauer, Johnny Hodges, George Van Eps, Benny Goodman, Lennie Niehaus, Ernie Henry, Lee Wiley, Jack Teagarden, Doug Watkins, Cecil Payne, Annie Ross, Roy Eldridge, Mundell Lowe, Dorothy Carless, Jutta Hipp, Bud Shank, Muggsy Spanier, Allen Eager & Brew Moore, Jane Fielding, Bob Brookmeyer, Charlie Mariano, Sam Most, Chico Hamilton, Barbara Lea, Joe Wilder, Hank Jones, Billy Taylor, Candido, Bennie Green, Jimmy Raney, Eddie Costa & Vinnie Burke, Buddy Collette, George Wallington, Tony Scott...and that's just from the first 400. The list actually encompasses 1200 albums, with Teddy Wilson on the penultimate page. In other words, if you wanted to do a blog just listening to 1956, you'd have your work cut out for you.

The New Yorker continued to favor Dixieland and trad jazz spots. The Five Spot opened in 1956, with Cecil Taylor leading the house trio, but it gets no mention. Still, they're beginning to do a little better. And New York was New York, the Big Apple. It was where musicians came, and you were always going to be able to hear great music. 52nd Street was mostly gone, except for the Dixieland at Jimmy Ryan's, but there was a surprising amount of jazz in midtown. Birdland was a relatively recent arrival on the venerable street of jazz, and a powerhouse, featuring Count Basie, Chris Connor, the MJQ, and Phineas Newborn.

The Metropole, on Times Square, always had an amazing retinue of traditional players. Louis Armstrong was at Basin Street at 51st and Broadway. Also Cameo, on E. 53rd, alternated Barbara Carroll and Teddy Wilson on piano, and a block north, The Embers had a quartet of Tyree Glenn, Jo Jones, Tommy Potter and Dick Katz. Childs Paramount, which can't have lasted very long but must have been some sort of joint venture between the Childs restaurant chain and the Paramount Hotel, had a heck of a New Year's Eve show with Buck Clayton Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge and PeeWee Russell leading an all star lineup.

In Greenwich Village, the Village Vanguard was already an institution, but not always a jazz institution. To usher in the new year, however, they presented Abbey Lincoln. The Cafe Bohemia on Barrow Street, home to some classic live albums, alternated quintets led by Max Roach and Lester Young, and would have been a great place to spend New Year's Eve.

On to 1957.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-6766535-1426183977-4881.jpeg.jpg) write one?" As Weinstock recalled, he recoiled from the idea--one thing he was sure of, he didn't know how to write a song. But Trane kept teasing him: "How about this?" and he'd play a few notes. If Weinstock said OK, he'd play a few more: "How about this?" Before long, they had strung something together, and Trane said, "OK, you wrote it."

write one?" As Weinstock recalled, he recoiled from the idea--one thing he was sure of, he didn't know how to write a song. But Trane kept teasing him: "How about this?" and he'd play a few notes. If Weinstock said OK, he'd play a few more: "How about this?" Before long, they had strung something together, and Trane said, "OK, you wrote it."

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1324250-1457055496-1590.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-831406-1254766358.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2937631-1308161023.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4728185-1378736078-7897.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7395628-1440590107-2769.jpeg.jpg)