LISTEN TO ONE: Evidence

Lacy is a particularly interesting figure in American music. His devotion to the compositions of Thelonious Monk are a part of it, and a not insignificant part. No one before him had treated a composer in the pure jazz idiom with this kind of seriousness. I'm hedging my bet here, categorizing Ellington as a crossover between jazz and popular song, Gershwin as crossover between jazz, Broadway and classical, thus violating all my principles about pigeonholing people into categories, but what the heck. It's still a valid point. And I don't think any progressive jazz musician had devoted a whole album to Ellington or Gershwin by 1961, either.

Lacy was also unusual in that he began by playing Dixieland, and went straight from there to the avant garde, with none of the usual stops in between. And he was unusual in that soprano sax. which is most commonly someone's "other instrument," was his only instrument. He discussed all of this in a 1980 interview in Calcutta, India, with two jazz enthusiasts, Ajoy Ray and Arthur Gracias. He began with his beginnings in music, at a later date than most, buying a soprano sax at age 16 after hearing a Sidney Bechet record. Interviewer Ray pointed out that the soprano is considered a particularly difficult instrument to play. Lacy laughed and said, "I didn't know that at the time!" Asked why he stuck with it to the exclusion of all other reed instruments, he said:

Because I found out how hard it was and therefore, I needed all my time to devote to that, do what I wanted to do, and I didn‟t have the time to do it. It's like having two wives, or 3 wives or 4 wives: couldn't do it, couldn't handle 'em.

By 19, he had progressed enough on this difficult instrument to begin playing professionally ("I didn't know what I was doing, but I didn't know I didn't know"), and the love of Bechet's music led him to gravitate toward traditional jazz:

I started playing with... mostly old guys. These were people 60years old, old pioneers who were still active in New York, like Red Allen, Hot Lips Page, Buck Clayton, Jimmy Rushing, Zutty Singleton, Pops Foster, the older cats. And I was just a kid, just 19 years old. And they were 65, but they were beautiful. They really encouraged me and showed me a lot of things.

But then...

In the middle of all that, I met Cecil Taylor and he just plucked me right out of all that and put me in the fire! Put me right into the deep waters you know! And I didn't know how deep the water was! So I swum across there for about 6 years with him. From '53 to '59.That was where I learnt a lot of stuff, playing with him.Ray: Wasn’t it a big switch; from the New Orleans style to C. Taylor? From one extreme to another?Lacy: Yeah, again I didn't know how big a switch it was! Didn't seem so big to me. And it still doesn't, in a way, because Jazz is much the same really. Surface characteristics and all that, it still contains the same spirit. Not so far really.

Ray Bryant felt much the same way when he would spend afternoons at the at the Metropole Cafe sitting in with Henry "Red" Allen, and the same evening downtown at the Five Spot playing with Benny Golson and Curtis Fuller: "A C chord is a C chord no matter where you find it. I never made a conscious effort to play differently with anyone."

This album features the only Prestige appearance of one of the most significant musicians of that era: Don Cherry, who came to New York with Ornette Coleman for the two weeks that shook the world, their groundbreaking Five Spot stay. Steve Lacy, in the 198o interview, recalls that group.

Oh, that was a revelation for everybody in New York. That was like the Message, the Writing on the Wall. Nobody could ignore that really. Either you're against it or for it. I mean it was like a big flash. Everybody was talking about it. You either liked it or you didn't. I liked it right away. But I had already played with Cecil (Taylor) for 6 years by the time I heard that. So it was revolutionary all right. But I had been involved in another revolution, or maybe the same revolution. So I felt right at home with that. We loved it.

Cherry remained in the vanguard of music for three decades, playing with avant garde musicians like Coleman, Lacy and Albert Ayler, playing with mainstream musicians like Sonny Rollins, playing world music, collaborating with classical composers.

Lacy bypassed many of the modern genres--bebop, hard bop, cool jazz, soul jazz. He told his 1980 interviewers:

I got there a little too late. Yeah very profound! I studied that music a lot. Charlie Parker was one of my masters. Dizzy Gillespie and Bud Powell and Kenny Clarke and Max Roach and Thelonious Monk. I think I was too young, too late for bebop. I started in 1950, and the height of bebop was '46, '47, '48, '49. By the '50s, it had already done its thing. It was going into a kind of repetition, the cool phase and what they call hard bop. I studied it the best I could and I tried to play it, but I was in the next generation, you know what I mean? I was in the generation after that. I tried to play the best I could, but I was too late really.

It's interesting, then, that Lacy should have become such an interpreter of Monk, who is so closely identified with the bebop era. But Monk was always a special case. He was in the bebop era but not entirely of it, and his compositions are his own, a unique music portfolio. The beboppers played Monk's tunes--not as many or as often as you might think--but the staples of their repertoire were standards, and compositions based on the chord changes of the standards, like the near-ubiquitous "I Got Rhythm."

Lacy hardly ever played a standard. He liked to explore the work of other jazz composers, like Charles Mingus, Herbie Nichols, and Mal Waldron, with whom he oftened collaborated in Europe when they had both gone the expatriate route.

And Duke Ellington, but you would hardly expect a disciple of Cecil Taylor and a compatriot of Ornette Coleman to play in the style of the Duke. The two Ellington compositions on this album, "The Mystery Song" and "Something to Live For" are not among the composer's best known, and I'm not sure that Duke's mother would recognize these versions of them.

The structure of these performances is not so strange. It would be recognizable to a bebop fan: head, series of solos, restatement of head. But what solos! Cherry brings his awareness that jazz has changed to this new setting, but he doesn't just bring over his Ornette Coleman Quartet style. He is very much working with Lacy here, and working with Monk. And both of them are creating something new and arresting, abetted by Coleman's drummer Billy Higgins, a presence throughout.

Bassist Carl Brown is something of a mystery. He only has two recording credits, this one and an unreleased trio session for Atlantic, with Billy Higgins. It has been speculated that this is Charlie Haden playing under an alias, but a contributor to a thread on an Organissimo.org forum (one of the best gathering spots for jazz insiders on the web) verifies that there was a real Carl Brown ("I heard him with Billy Higgins and Clarence "C" Sharpe in the Village early sixties").

This is a particularly interesting session, just for the pure enjoyment of the music, but also for the historical interest of two giants of two different avant garde schools of the mid-twentieth century, meeting and finding common ground. And for a new way of experiencing the composing genius of Thelonious Monk.

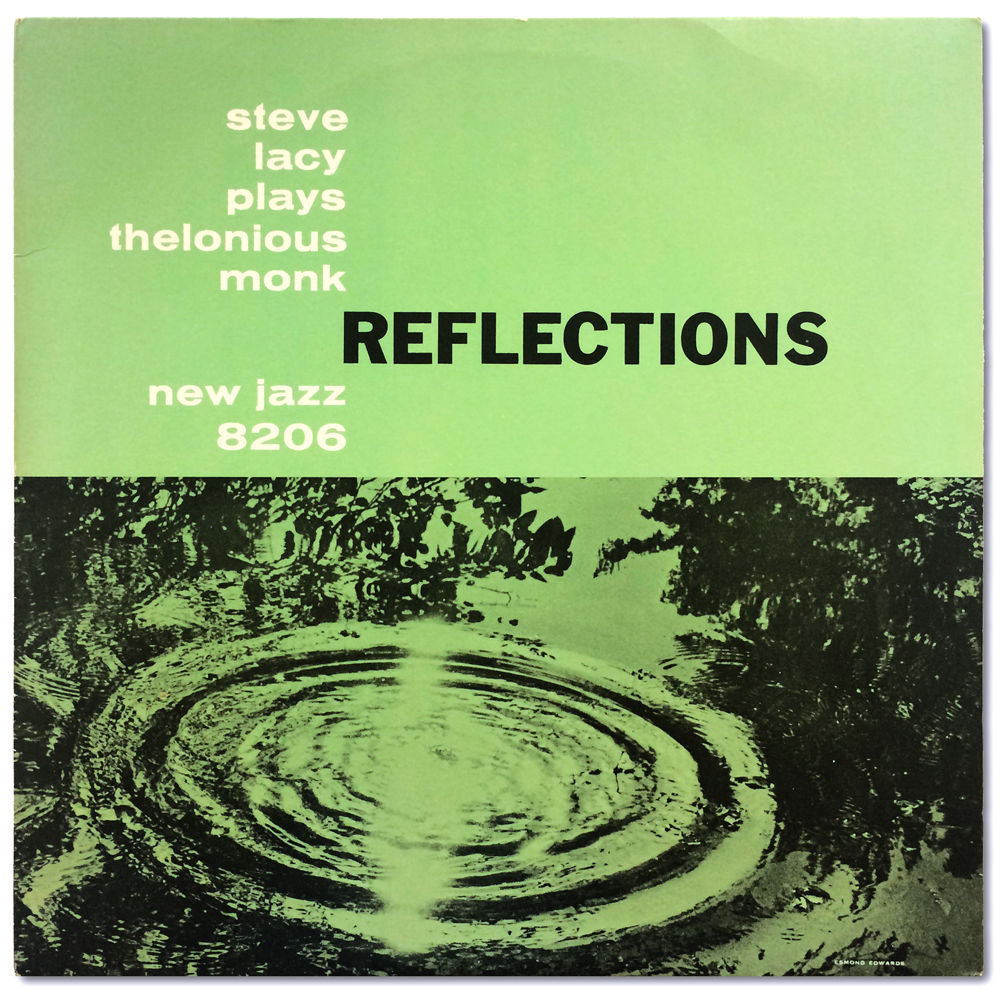

Esmond Edwards produced. The album, titled Evidence, was released on New Jazz.