Tad Richards' odyssey through the catalog of Prestige Records:an unofficial and idiosyncratic history of jazz in the 50s and 60s. With occasional digressions.

Friday, August 29, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records, part 26: Stan Getz

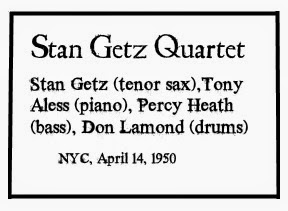

You know how when you hear a word you've never heard before, suddenly everyone seems to be using it -- seems like everyone else except you knew it all the time? Jimmy Hatlo even devoted one of his "They'll Do It Every Time" cartoons to this theme, so thanx and a tip of the Hatlo hat, Jimmy, and it's happening to me with musicians instead of words. No sooner do I mention never having heard of Tony Aless than he shows up again, this time as part of a Stan Getz Quartet.

Perhaps there's something to be said for the theory that a jazz recording session is quite likely to involve a group made up of whoever's around. Tony Aless and Don Lamond had both played on the Chubby Jackson session a month earlier and so were quite likely still kicking around 52nd Street. And Getz would have known them because they were both -- as were so many early Prestige artists -- Woody Herman veterans.

Percy Heath has a credit that I'd venture to guess no other jazzman has: he was a member of the Tuskegee Airmen, the famed African-American military aviators of World War II. He has impressive jazz credits, too, including being a member, with his brothers, of one of the first families of jazz.

One of the joys that the great balladeers like Stan Getz bring to jazz is their way with classic songs from what has come to be known as the Great American Songbook. These are vivid and memorable melodies, with chord changes and melodic structures that lend themselves to jazz interpretation and improvisation.

But they're more than that. They're songs, with the emotional and thematic power that only a song can deliver. Lester Young said that he always heard the words to a song in his head as he played it. The fictional Dale Turner, played by Dexter Gordon in the movie "Round Midnight," has a moment when he realizes he's losing his ability to produce the music he wants to, and says, "I forgot the words." I don't know if Stan Getz played the words in his head when he recorded a ballad, but he captures the feeling of each of these.

Of course, music is abstract. If you didn't know the story of Peter and the Wolf, you wouldn't just be able to conjure up ducks and wolves and hunters from the music itself. But if you know the songs, Getz brings something palpable to them.

In "You Stepped Out of a Dream," that rapt wonder that only the person you've suddenly, unreservedly fallen in love with can evoke. Written by Nacio Herb Brown and Gus Kahn, it was originally sung by Tony Martin for the 1941 musical Ziegfeld Girl, to the visual of Lana Turner descending a staircase. Brown isn't quite on the Olympus of American songwriters, but he was good enough to dream, and good enough to write some melodies that are remembered.

"My Old Flame" is a song that was brilliantly subverted and destroyed by Spike Jones. It was written by Arthur Johnston and Sam Coslow, who also saw their other hit, "Cocktails for Two," similarly demolished by Spike Jones. So Getz is not going her for the A-list of American composers, but he's finding some fine melodies, and in this case, restoring the feeling that Johnston and Coslow must have meant it to have: sweet nostalgia, regret.

I didn't know "The Lady in Red," so I listened to the Mark Murphy version and the Louis Prima version. I missed the Bugs Bunny version, "The Rabbit in Red," so I guess this was an eminently wreckable song too -- and again by a good, but B-list composer, Allie Wrubel. And this one bright, vivacious, sparkling. All these not-quite-great songwriters taken over the top, into immortality, by a true great, Stan Getz.

"Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams," by songwriters I really hadn't heard of - Harry Barris, Ted Koehler, Billy Moll. Getz captures the dreamy optimism that comes out sadness. You wouldn't have to wrap your troubles in dreams and dream your troubles away if you didn't have troubles.

All these songs are about loss, and about an at best evanescent reality. Losses that you have to dream away, but you never really can. The fading memory of an old flame. The girl who steps out of a dream -- she's Lana Turner, and you'll never have her. She'll never really detach from that dream. Even the vivacious, snazzy lady in red -- you'll never have her either.

Stan Getz was a poet of loss, right up to that girl walking across the beach, looking straight ahead, not at you.

Released on Prestige and New Jazz 78s and 10-inchers, Prestige EP, even a 45 (My Old Flame/The Lady in Red), and later on a 7000-series reissue, a 24000-series double LP, even on an New Jazz LP when that line was briefly restarted.

Wednesday, August 27, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records, part 25: Lee Konitz

Lee Konitz back in the Prestige studios again, April 7, 1950, seven months after the first session. still in the Tristano circle, this time without Warne Marsh or Denzil Best. In Best's place, Jeff Morton, about whom I can find no information whatsoever, which seems strange, given that he played on quite a number of sessions within the Tristano circle, and you had to be pretty advanced musically to play in that circle. Sal Mosca, in an interview, says that he was usually the drummer at Tristano's Saturday night jam sessions. His presence is felt here, especially on the uptempo numbers, and it's a strong one.

And on guitar, Billy Bauer. And he is a treat to listen to, whether playing the guitar like a percussion instrument, chording, or playing single-string runs.

And on guitar, Billy Bauer. And he is a treat to listen to, whether playing the guitar like a percussion instrument, chording, or playing single-string runs.

The tunes today are two ballads, "Rebecca" and "You Go to My Head," and two uptempo numbers, "Ice Cream Konitz" and "Palo Alto." The ballads are demanding, but far from emotionally barren. The uptempo numbers are virtuoso performances from all concerned. "Ice Cream Konitz" is a good argument for why modern jazz players should maybe have retired the fad of punning on their own names; "Palo Alto" is a subtler pun, more befitting a Tristano acolyte. Either way, they swing both subtly and forcefully, and interplay between guitar, piano and alto is more than satisfying,

I had a friend who took lessons from Bauer many years ago. He said that for the first half-hour, Bauer had him do nothing but play the same note on the same string, over and over, while he kept saying, "Swing...swing." "And when it was over," my friend said, "I was swinging!"

I linked above to an interview with Sal Mosca. Here are a couple of excerpts from it.

These sessions were released on both Prestige and New Jazz 78s, on an EP called Lee Konitz with Billy Bauer, on a 10-inch called Stan Getz/Lee Konitz - The New Sounds, and on 7000-series LP called Lee Konitz With Tristano, Marsh And Bauer.

And on guitar, Billy Bauer. And he is a treat to listen to, whether playing the guitar like a percussion instrument, chording, or playing single-string runs.

And on guitar, Billy Bauer. And he is a treat to listen to, whether playing the guitar like a percussion instrument, chording, or playing single-string runs.The tunes today are two ballads, "Rebecca" and "You Go to My Head," and two uptempo numbers, "Ice Cream Konitz" and "Palo Alto." The ballads are demanding, but far from emotionally barren. The uptempo numbers are virtuoso performances from all concerned. "Ice Cream Konitz" is a good argument for why modern jazz players should maybe have retired the fad of punning on their own names; "Palo Alto" is a subtler pun, more befitting a Tristano acolyte. Either way, they swing both subtly and forcefully, and interplay between guitar, piano and alto is more than satisfying,

I had a friend who took lessons from Bauer many years ago. He said that for the first half-hour, Bauer had him do nothing but play the same note on the same string, over and over, while he kept saying, "Swing...swing." "And when it was over," my friend said, "I was swinging!"

I linked above to an interview with Sal Mosca. Here are a couple of excerpts from it.

At first, I did not like Charlie Parker. Lennie Tristano had me sing a solo of Parker’s. It was Scrapple From the Apple. It took me one and ½ years to learn to sing it, and another six months to play it on the piano. When I was able to play it, I began to love Charlie Parker and my love of his playing grew and continued after that.

[On classical pianists] I prefer Horowitz. He is more romantic. He’s the closest to jazz of all the classical pianists. I heard a recording of Horowitz playing Mozart, it sounded like stride piano. Did you know that he went often to hear Tatum?

These sessions were released on both Prestige and New Jazz 78s, on an EP called Lee Konitz with Billy Bauer, on a 10-inch called Stan Getz/Lee Konitz - The New Sounds, and on 7000-series LP called Lee Konitz With Tristano, Marsh And Bauer.

Monday, August 25, 2014

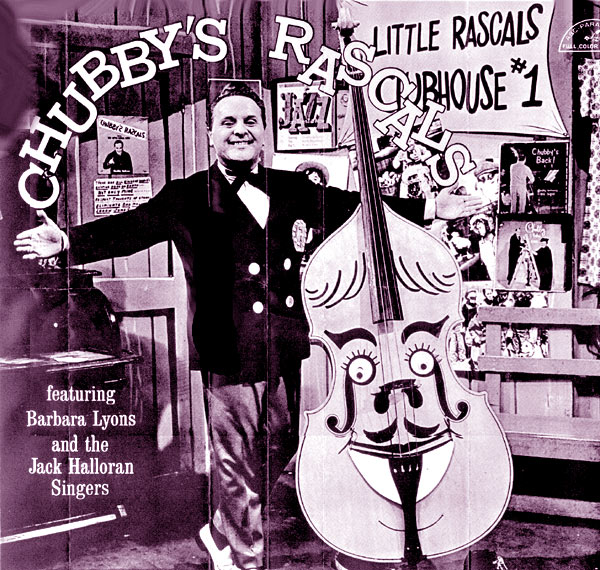

Listening to Prestige Records, part 24: Chubby Jackson

The most recent rerelease of this 1950 Prestige session is on an Original Jazz Classics CD (Concord's reissue label - they currently own the Prestige catalog) along with some of the classic Gerry Mulligan/Chet Baker quartet recordings. Most of the consumer reviews on Amazon praise the quartet sessions, understandably, but then they tend to say some variation of "oh, and there's also some stuff by a big band."

I wonder if it had been called the Gerry Mulligan Big Band, would that have earned it more respect? But this is a terrific band, a terrific group of songs.

Arranged by Mulligan? Probably. Maybe. There's no arranger credit for the session, but at this stage of his career Mulligan was better known as an arranger than as a saxophone player, and it's likely that if he was on the session, he'd also have been hired to arrange. Some of the tunes certainly sound like Mulligan arrangements, some not so much. We know that Al Cohn did some arranging for the 1949 version of the Chubby Jackson Big Band, and Tiny Kahn was its chief arranger, so one or both of them may have had a hand, although neither played on this date.

Big band bebop is almost an oxymoron. Bebop was a product of the breakup of the big bands, a style that favored listening over dancing, extended virtuoso solos over ensemble section play. But it was always part of the scene. The Billy Eckstine band hired Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker; also a Miles Davis, Fats Navarro and Dexter Gordon. Gillespie had his own big band. The Woody Herman Herd, where Chubby Jackson got his start, wasn't exactly bebop, but it wasn't exactly the swing of the Thirties, either.

And this band of Jackson's is as good as a bebop big band gets. It has swinging but ambitious ensemble parts, lots of room for experimental solos.

Chubby Jackson himself had a checkered career (note to self: when you make an accidental bad pun, for God's sake take it out in the second draft! Reply from self: What second draft?) -- anyone who has performed with both Louis Armstong and Lennie Tristano has run a fairly complete gamut, and let's not forget his twist album. And he's probably the only serious jazz musician who was also a TV kiddie show host (Chubby Jackson's Little Rascals).

Chubby Jackson himself had a checkered career (note to self: when you make an accidental bad pun, for God's sake take it out in the second draft! Reply from self: What second draft?) -- anyone who has performed with both Louis Armstong and Lennie Tristano has run a fairly complete gamut, and let's not forget his twist album. And he's probably the only serious jazz musician who was also a TV kiddie show host (Chubby Jackson's Little Rascals).

I listened to these sides a couple of times before I really looked at the lineup of musicians. I'd noticed that Mulligan and Zoot Sims were included, hadn't paid close attention to the others. So when I found myself particularly taken by the piano solos, I went back to see which of the bebop legends Jackson had recruited for this date, I was surprised to find a name I'd never heard: Tony Aless. But Aless did some impressive work, going back to Bunny Berrigan in the Thirties, and including sessions with Woody Herman, Stan Getz and Charlie Parker.

Peter Jones, who knows more about jazz than I do, was familiar with Aless, but asked, "who is Charlie Kennedy on alto-- he sounds a lot like Lee Konitz?"

So many great jazzmen who didn't break through to create major names for themselves. Charlie Kennedy started with Louis Prima, went on to become a soloist with Gene Krupa's big band. His last major gig was with Terry Gibbs' Dream Band, before he retired from music in the early 60s.

The rest of the band is a dream band, and they play like it.

"I May Be Wrong," which Mulligan was later to recreate as a cool, wryly romantic ballad with his quartet, is given as a joyous romp here - with Mulligan's fingerprints on it. "Sax Appeal" has some particularly appealing work between ensemble and soloists.

And what's this number called "So What"? It appears to be a Mulligan composition. Surely it's a Mulligan arrangement. The notes say it is not the composition of the same name by Miles Davis for the "Kind of Blue" album, and certainly there's a world of difference between the hip, cool modality of the Miles Davis number and this piece of beboppery. You could say that the Davis piece makes the Jackson band's piece sound old-fashioned, except it doesn't -- bebop still has the freshness and power to excite, and so does Mulligan at every phase of his career.

Here's "So What," from a new site to me, but it looks like a good one, called Jukebo. I can't seem to get their embed code to work, so I'm just providing a link. In this version, the song has a subtitle, "Hoo Hah," which I suspect is to differentiate it from the Davis number.

Prestige issued these as 78s on both Prestige and New Jazz, with records credited variously to Jackson, Mulligan and Zoot Sims, then on 45 RPM EPs and a 10-inch LP, and finally as part of a 7000-series LP called Chubby Jackson Sextet and Big Band -- nice of them to give the credit to Jackson, as Mulligan by then was by far the bigger star.

Friday, August 22, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records, Part 23: Gene Ammons/Sonny Stitt

So I'm sitting in a club listening to a group led by J. R. Monterose, at a front table, and after a solo J. R. comes and sits with me, and we're talking a little -- quietly, respectfully, listening to the music -- as the other members of the group go through their solos. Suddenly, in mid-sentence, he stands up, gets back up on the bandstand, waits a couple of beats, and comes in right on cue.

But what cue? A nod of the head or a hand signal that he was watching for and I wasn't? A prearrangement that each soloist would play a certain number of bars, and while sitting and chatting with me he's also counting them out? I couldn't even do that if I were in an isolation booth, tapping it out with my feet. A sixth sense that tells him when the soloist is going to run out of ideas? We know that John Coltrane could solo virtually forever. When Miles Davis commented on it, Coltrane said that sometimes he just didn't know how to stop. Davis's suggestion: "Try taking the horn out of your mouth."

Which conceivably could have cued J. R. - the other guy takes the horn out of his mouth, or lifts his hands up off the keyboard -- if J. R. Is standing next to him on the bandstand, not anticipating and getting out of his chair and climbing back up on the bandstand.

All of which goes to make my oft-made point that I am not writing this as a music professor, or musicologist, or musician, or musical anything but fan. Larry Audette, or some other jazz musician who might be reading this, can certainly tell me how this works.

And all of which brings me around to Sonny Stitt once again, back in the studio for two more Prestige sessions, the first with Gene Ammons -- two classic bebop tenors, playing off a loose structure that gives plenty of room for improvisation trading lines of unequal length back and forth with casual intricacy that leaves me wondering "how do they do it?" But mostly just appreciating that they're doing it.

We know it wasn't rehearsed, because Bob Weinstock didn't allow for rehearsal, and in any case, you couldn't really rehearse that sort of improvisational give and take. I guess you could write a chart -- I'll take twelve bars and then you take four and then I'll take four and then you take eight but I'll overlap the last one...but I don't think so.

I only found two selections - "Blues Up and Down" and "You Can Depend on Me" - on a Spotify, so they were my car listening, but a third, "Bye Bye," with some propulsive drumming by Jo Jones, was on a site that was new to me -- Shelf3d. I can't embed it, but i can link to it. "Blues Up and Down" and "You Can Depend on Me"are both just the quintet, Stitt, Ammons, rhythm section.

"Blues Up and Down" Is represented in three takes. Sometimes a plethora of alternate takes can be a nuisance if you're listening to a CD, but if you're doing a close and repeated listen to just a few tunes, it's fascinating. The first take of "Blues Up and Down" is good (though incomplete - they stop halfway through), but the second take is where it really comes together. The opening chorus is now more than just a riff, and the solos take flight. The third take may be tighter, or it may just be that they needed a third because it's the only one they actually finish, but I do love the second. I don't hear a lot of difference in the two takes of "You Can Depend on Me" (and there's only a couple of seconds difference in time) but they both sound good.

"Blues Up and Down" Is represented in three takes. Sometimes a plethora of alternate takes can be a nuisance if you're listening to a CD, but if you're doing a close and repeated listen to just a few tunes, it's fascinating. The first take of "Blues Up and Down" is good (though incomplete - they stop halfway through), but the second take is where it really comes together. The opening chorus is now more than just a riff, and the solos take flight. The third take may be tighter, or it may just be that they needed a third because it's the only one they actually finish, but I do love the second. I don't hear a lot of difference in the two takes of "You Can Depend on Me" (and there's only a couple of seconds difference in time) but they both sound good.

On the same day, they backed up a vocalist named Teddy Williams -- essentially the same session, but it's listed as a Teddy Williams session because the 78 was issued under his name - later rereleased on LP as both a Stitt Session and an Ammons session -- and much later, as part of a box set called "Stitt's Bits: The Bebop Recordings," although there's not much bebop in evidence on these two tracks, although lord knows they're different enough from each other. They're both on Spotify.

On the first, "A Touch of the Blues," Williams is not particularly singing much more than a touch of the blues. It's a ballad in that Billy Eckstine style - more like Al Hibbler, really - and Stitt and Ammons play a chart that seems to have been written for a big band reed section. On the second, "Dumb Woman Blues," Williams belts out a conventional 12 bar blues in the style of Wynonie Harris or Roy Brown. And the horns play riffs that could easily be from a Wynonie Harris session, with one solo break (Ammons? I'm not good enough to be sure) that takes into that blue-gray area between bebop and rhythm and blues -- an area that's always interested me. Back in the day, the jazz tastemakers disdained rhythm and blues. Symphony Sid, if a caller requested Ray Charles, would answer scornfully, "We don't play rock and roll." But the same was not true of musicians. On Slim Gaillard's "Slim's Jam," Charlie Parker jams with "MacVoutie" - Jack McVea, best known for the R&B novelty smash "Open the Door, Richard," and another R&B bandleader, Paul Williams, had his biggest success with "The Hucklebuck," which is essentially Charlie Parker's "Now's the Time." Many jazz musicians, including such pinnacles of refinement as the MJQ's Connie Kay, played R&B dates.

Oh, and maybe I'm not the musical dunce I think I am. Well, I am, but maybe I'm not the only one. The reviewer of the Stitt-Ammons sessions on AllMusic.com says "at times, when [Stitt] and Gene Ammons are dueling on tenors, it's difficult to tell the difference between them," whereas the Amazon reviewer talks about "the contrast between Stitt's swift, complex phrases and Ammons's gruff passion" (how's that for bebop meets R&B?) I'm with the Amazon guy.

Monday, August 18, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records, Part 22: Al Haig

Next up on the Jazz Discography Project is a Charlie Parker session, and that got my juices flowing, because there's still no more magical name in jazz than Charlie Parker. But I can't include it. Jazzdisco lists every session that eventually got released by Prestige, so this one is included, but it was only a rerelease package put out in 1973, by which time there was really no more Prestige. In 1971 it had been sold to Fantasy, a West Coast label, and it was essentially just a reissue house.

I don't know yet how long I'll keep this blog going. Maybe 1971 is a good year to stop. I'd been thinking 1969, which would give me a twenty year run. I'll have to see how thin the pickings get as we get farther into the 60s -- I'm making a point of not looking ahead, but letting things unfold to me as they unfolded in those years. And remember, to me this is still history. I was ten years old in 1950, and had never heard of jazz.

So anyway, the Charlie Parker set is a live recording from St. Nicholas Arena, mostly known for boxing, so fight fan Miles Davis would have felt right at home had he still been with the group, but he wasn't. Red Rodney was the trumpeter, and the rhythm section was Al Haig, Tommy Potter, and Roy Haynes.

Stick around with that rhythm section, however, because they're next on deck. There are two more European recordings (the Jacques Dieval Quintet with Peck and Moody again, this time Annie Ross one song, but it can't be found at any of my sources; a Swedish group led by Arne Domnerus), and on February 27, the Al Haig Trio.

They recorded four songs -- "Liza," "Stars Fell on Alabama," "Stairway to the Stars," and "Opus Caprice" -- the last an Al Haig composition, and all of them, for whatever reason, songs he had also recorded with Stan Getz.

Of them, none can be found on YouTube, and only "Liza" on Spotify. If you want to share this listening experience with me, and you're a Spotify subscriber, you can follow me, or connect with me through Facebook, and I'll share my "Prestige" playlist with you -- whatever Prestige recording session I'm listening to on that day. Or you can just find the songs yourself. If you have a really great vinyl collection, of course, you can just go straight to the source -- like this 45 RPM EP.

Today, my playlist only has one song on it -- "Liza." So plenty of leisure to give it several listens, and really appreciate how good Al Haig -- not just as an accompanist, but as a soloist. Influenced as much by Monk as by Bud Powell, but very much his own man. I'm guessing he wasn't in that much demand as a leader, but if this is any guide, he should have been.

Tommy Potter steps out in front too, and acquits himself wonderfully. I'm trying to think if there were any superstars of the bass during this period, other than Charles Mingus. People like Paul Chambers came later. Ray Brown was around, but I don't think he was out front much in those years. Oscar Pettiford, probably. Jimmy Blanton, certainly, but he died so young. Slam Stewart, but in a different context. Tommy Potter and Curly Russell were the backbone of so much of bebop, and you read so little about them, but they were so important.

I can't hear Roy Haynes's name in my head without hearing Sarah Vaughan, on "Shulie a Bop" (on Mercury), introducing "Roy...(drumroll)...Haynes (drumroll)!" Haynes is still alive, still performing, still great.

And me...listening to "Liza" one more time. and wishing I had the rest of the session.

I don't know yet how long I'll keep this blog going. Maybe 1971 is a good year to stop. I'd been thinking 1969, which would give me a twenty year run. I'll have to see how thin the pickings get as we get farther into the 60s -- I'm making a point of not looking ahead, but letting things unfold to me as they unfolded in those years. And remember, to me this is still history. I was ten years old in 1950, and had never heard of jazz.

So anyway, the Charlie Parker set is a live recording from St. Nicholas Arena, mostly known for boxing, so fight fan Miles Davis would have felt right at home had he still been with the group, but he wasn't. Red Rodney was the trumpeter, and the rhythm section was Al Haig, Tommy Potter, and Roy Haynes.

Stick around with that rhythm section, however, because they're next on deck. There are two more European recordings (the Jacques Dieval Quintet with Peck and Moody again, this time Annie Ross one song, but it can't be found at any of my sources; a Swedish group led by Arne Domnerus), and on February 27, the Al Haig Trio.

They recorded four songs -- "Liza," "Stars Fell on Alabama," "Stairway to the Stars," and "Opus Caprice" -- the last an Al Haig composition, and all of them, for whatever reason, songs he had also recorded with Stan Getz.

Of them, none can be found on YouTube, and only "Liza" on Spotify. If you want to share this listening experience with me, and you're a Spotify subscriber, you can follow me, or connect with me through Facebook, and I'll share my "Prestige" playlist with you -- whatever Prestige recording session I'm listening to on that day. Or you can just find the songs yourself. If you have a really great vinyl collection, of course, you can just go straight to the source -- like this 45 RPM EP.

Today, my playlist only has one song on it -- "Liza." So plenty of leisure to give it several listens, and really appreciate how good Al Haig -- not just as an accompanist, but as a soloist. Influenced as much by Monk as by Bud Powell, but very much his own man. I'm guessing he wasn't in that much demand as a leader, but if this is any guide, he should have been.

Tommy Potter steps out in front too, and acquits himself wonderfully. I'm trying to think if there were any superstars of the bass during this period, other than Charles Mingus. People like Paul Chambers came later. Ray Brown was around, but I don't think he was out front much in those years. Oscar Pettiford, probably. Jimmy Blanton, certainly, but he died so young. Slam Stewart, but in a different context. Tommy Potter and Curly Russell were the backbone of so much of bebop, and you read so little about them, but they were so important.

I can't hear Roy Haynes's name in my head without hearing Sarah Vaughan, on "Shulie a Bop" (on Mercury), introducing "Roy...(drumroll)...Haynes (drumroll)!" Haynes is still alive, still performing, still great.

And me...listening to "Liza" one more time. and wishing I had the rest of the session.

Listening to Prestige Records, Part 21: Sonny Stitt

A gap in the timeline. Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis recorded four sides for Prestige on February 7, 1950, but while Davis is widely represented on both Spotify and YouTube, I can't find this session anywhere. Too bad. Davis was joined by Al Casey, already an oldtimer in 1950 (I heard him play in the '90s with the Harlem Blues and Jazz Band), a veteran of Fats Waller's band among others; and 19-year-old Wynton Kelly, in his first recording session. Two cuts had vocals by R&B vocalist "Chicago" Carl Davis, which makes me really sorry not to have found it -- I'm always interested in the overlap between modern jazz and rhythm and blues in this time period.

Then two European sessions, one led by French pianist Jacques Dieval, about whom even the French Wikipedia has next to nothing (but James Moody and Nat Peck played on the two-song date), and the other by a Swedish group led by vibraphonist Ulf Linde.

So the next session we have access to is Sonny Stitt again, this time with a different group of sidemen, including Art Blakey, who's most associated with Blue Note, where the Jazz Messengers recorded a lot of their albums, but who had a Prestige presence as well. Blakey, ageless and prolific, actually recorded for a lot of labels.

So the next session we have access to is Sonny Stitt again, this time with a different group of sidemen, including Art Blakey, who's most associated with Blue Note, where the Jazz Messengers recorded a lot of their albums, but who had a Prestige presence as well. Blakey, ageless and prolific, actually recorded for a lot of labels.

Without Bud Powell, most of the solo space here goes to Stitt, and the session is more ballad-oriented. Of the selections, I especially liked "Mean to Me," which is a beautiful melody, and lends itself to bluesy improvisation.

This was another of the handful of recordings originally released on the Birdland label.

Then two European sessions, one led by French pianist Jacques Dieval, about whom even the French Wikipedia has next to nothing (but James Moody and Nat Peck played on the two-song date), and the other by a Swedish group led by vibraphonist Ulf Linde.

So the next session we have access to is Sonny Stitt again, this time with a different group of sidemen, including Art Blakey, who's most associated with Blue Note, where the Jazz Messengers recorded a lot of their albums, but who had a Prestige presence as well. Blakey, ageless and prolific, actually recorded for a lot of labels.

So the next session we have access to is Sonny Stitt again, this time with a different group of sidemen, including Art Blakey, who's most associated with Blue Note, where the Jazz Messengers recorded a lot of their albums, but who had a Prestige presence as well. Blakey, ageless and prolific, actually recorded for a lot of labels.Without Bud Powell, most of the solo space here goes to Stitt, and the session is more ballad-oriented. Of the selections, I especially liked "Mean to Me," which is a beautiful melody, and lends itself to bluesy improvisation.

This was another of the handful of recordings originally released on the Birdland label.

Saturday, August 16, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records, Part 20: Sonny Stitt/Bud Powell

When Chuck Berry said he had no kick against modern jazz, except they try to play it too darn fast, he had to have been thinking of sessions like this one -- Sonny Stitt leading the same group six weeks later, and this time tearing through four uptempo numbers - five if you count the alternate take on "Fine and Dandy."

This group features the men who revolutionized modern music, but two who especially revolutionized it. Max Roach, with Kenny Clarke, changed the way that drums were played, moving the beat to the lighter, more flexible high-hat cymbal, and using the bass drum for accents. Bud Powell changed the way that the piano was played, giving a different role to the left hand. This led to the denigration of modern players as one-handed. Art Tatum, in particular, was initially disdainful of Powell, declaring that he could only play with one hand, until Powell proved him wrong by playing a tricky uptempo solo entirely with his left hand.

But Berry was wrong, of course. It's fast, but not too darn fast. In the hands of masters like these, the speed is exhilarating and joyous, and the complexity and surprises of bebop only make it more so.

These are songs I wouldn't have thought of as jazz standards, especially "Strike up the Band" and "I Want to Be Happy," but actually they've been recorded by others -- Art Farmer, Stan Getz and Red Garland have all found ways to jazz up George Gershwin's version of marching band music, and Ella Fitzgerald and princess of Cool Chris Connor have done vocal versions.

This is great stuff, alive and thrilling. You've gotta listen.

This group features the men who revolutionized modern music, but two who especially revolutionized it. Max Roach, with Kenny Clarke, changed the way that drums were played, moving the beat to the lighter, more flexible high-hat cymbal, and using the bass drum for accents. Bud Powell changed the way that the piano was played, giving a different role to the left hand. This led to the denigration of modern players as one-handed. Art Tatum, in particular, was initially disdainful of Powell, declaring that he could only play with one hand, until Powell proved him wrong by playing a tricky uptempo solo entirely with his left hand.

But Berry was wrong, of course. It's fast, but not too darn fast. In the hands of masters like these, the speed is exhilarating and joyous, and the complexity and surprises of bebop only make it more so.

These are songs I wouldn't have thought of as jazz standards, especially "Strike up the Band" and "I Want to Be Happy," but actually they've been recorded by others -- Art Farmer, Stan Getz and Red Garland have all found ways to jazz up George Gershwin's version of marching band music, and Ella Fitzgerald and princess of Cool Chris Connor have done vocal versions.

This is great stuff, alive and thrilling. You've gotta listen.

Thursday, August 14, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records, Part 19: Stan Getz

Bob Weinstock seems to have entered into a short-lived partnership with Morris Levy, who was among other things the owner of Birdland, to form a record company called Birdland Records. It's probably just as well for Weinstock that it was short-lived, since Levy was quite likely the crookedest crook in a business not entirely known for honesty. Levy was known, among other things, for his skill with white-out -- taking the names of actual songwriters off of the papers filed with the US copyright office and substituting his own. In a posthumous suit against Levy, Herman Santiago and Daniel Negron, two of the writers of "Why Do Fools Fall In Love," one of the biggest hit songs of all time, testified that they had made a total of $1000 off the song, and that Levy had threatened to kill Santiago if he came around asking for more.

In any event, Birdland Records seems to have put out a handful of 78s in 1950, the first of them coming from this session with Stan Getz and a half-new quartet from his June 1949 session -- Al Haig is there, but now he's joined by Tommy Potter and Roy Haynes -- a quintessential bebop lineup. On two of the cuts there are vocals by Junior Parker, later to become known as one of the great rhythm and blues singers.*

In any event, Birdland Records seems to have put out a handful of 78s in 1950, the first of them coming from this session with Stan Getz and a half-new quartet from his June 1949 session -- Al Haig is there, but now he's joined by Tommy Potter and Roy Haynes -- a quintessential bebop lineup. On two of the cuts there are vocals by Junior Parker, later to become known as one of the great rhythm and blues singers.*

Jazzdisco.org is a stunningly complete discography of Prestige's catalog by recording date, and invaluable. Another site, rateyourmusic.com, which has a dizzying plethora of lists compiled by fans and organized by some algorithm I couldn't begin to guess at, is less complete but pretty accurate as near as I can make out, and they have a variety of lists by release date. They have both the Birdland 78s and the Prestige 700-series of this session coming out in 1950, so Birdland must have been very short-lived indeed.

The songs on this date are mostly standards --"Stardust," "Goodnight, My Love," "There's A Small Hotel," "Too Marvelous For Words," "I've Got You Under My Skin," "What's New," "Intoit." "Goodnight, My Love" (not the rhythm and blues standard by Jesse Belvin; this is a song originally introduced by Shirley Temple) and "Stardust" get the Junior Parker vocals, and he is singing in a style distinctly different from his later R&B recordings. Here he seems to have been heavily influenced by Billy Eckstine.

The songs on this date are mostly standards --"Stardust," "Goodnight, My Love," "There's A Small Hotel," "Too Marvelous For Words," "I've Got You Under My Skin," "What's New," "Intoit." "Goodnight, My Love" (not the rhythm and blues standard by Jesse Belvin; this is a song originally introduced by Shirley Temple) and "Stardust" get the Junior Parker vocals, and he is singing in a style distinctly different from his later R&B recordings. Here he seems to have been heavily influenced by Billy Eckstine.

Eckstine is probably not as highly regarded today as he once was -- too florid to be a really successful jazz singer. But he was important in the history of modern jazz -- the first bandleader to give Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie a prominent role. And he influenced other jazz singers who are little remembered, like Kenny "Pancho" Hagood and -- had he not returned to his blues roots -- Junior Parker.

Eckstine was a little too florid, and his imitators a lot too florid -- especially when matched with Getz, who is certainly a romantic, but a drier, more modern romantic. He can unquestionably work with a singer -- "The Girl From Ipanema" proves that -- but he's not a good fit with Parker, or Parker is not a good fit for him. They say that along with the violin, the tenor saxophone is the instrument most alike in quality to the human voice, and on these standards, Getz sings. I love all of them -- even the Parker "Stardust," which grows on you, but mostly the instrumentals -- but perhaps "Too Marvelous for Words" more than any. "Too Marvelous" has a beautiful melody by Richard Whiting, and clever lyrics by Johnny Mercer, but...rather than hearing someone expend a whole lot of words to tell me that words won't do the job, I'd rather hear someone use words to do the job, as in "There's a Small Hotel" (Lorenz Hart) or "I've Got You Under My Skin" (Cole Porter).

Al Haig takes some terrific solos here too, but mostly it's Getz, Getz, Getz, and Getz at his youthful best.

Al Haig takes some terrific solos here too, but mostly it's Getz, Getz, Getz, and Getz at his youthful best.

These also came out on 45 RPM -- rateyourmusic.com is a little vague on the 45s, but I'd guess maybe still in 1950, more likely in 1951 -- and on their 10 inch LP series -- along with the previous Getz session -- in 1951.

* In no biography or discography of Junior Parker that I've been able to find online -- and some of them are pretty complete -- is there a reference to this session with Stan Getz. All the ones I've seen have him first recording with Modern in 1952. But I'm fairly certain it's the same guy. If it turns out I'm wrong, and this is just a curious coincidence of names, I will eat crow. For now, I claim a discovery.

In any event, Birdland Records seems to have put out a handful of 78s in 1950, the first of them coming from this session with Stan Getz and a half-new quartet from his June 1949 session -- Al Haig is there, but now he's joined by Tommy Potter and Roy Haynes -- a quintessential bebop lineup. On two of the cuts there are vocals by Junior Parker, later to become known as one of the great rhythm and blues singers.*

In any event, Birdland Records seems to have put out a handful of 78s in 1950, the first of them coming from this session with Stan Getz and a half-new quartet from his June 1949 session -- Al Haig is there, but now he's joined by Tommy Potter and Roy Haynes -- a quintessential bebop lineup. On two of the cuts there are vocals by Junior Parker, later to become known as one of the great rhythm and blues singers.*Jazzdisco.org is a stunningly complete discography of Prestige's catalog by recording date, and invaluable. Another site, rateyourmusic.com, which has a dizzying plethora of lists compiled by fans and organized by some algorithm I couldn't begin to guess at, is less complete but pretty accurate as near as I can make out, and they have a variety of lists by release date. They have both the Birdland 78s and the Prestige 700-series of this session coming out in 1950, so Birdland must have been very short-lived indeed.

The songs on this date are mostly standards --"Stardust," "Goodnight, My Love," "There's A Small Hotel," "Too Marvelous For Words," "I've Got You Under My Skin," "What's New," "Intoit." "Goodnight, My Love" (not the rhythm and blues standard by Jesse Belvin; this is a song originally introduced by Shirley Temple) and "Stardust" get the Junior Parker vocals, and he is singing in a style distinctly different from his later R&B recordings. Here he seems to have been heavily influenced by Billy Eckstine.

The songs on this date are mostly standards --"Stardust," "Goodnight, My Love," "There's A Small Hotel," "Too Marvelous For Words," "I've Got You Under My Skin," "What's New," "Intoit." "Goodnight, My Love" (not the rhythm and blues standard by Jesse Belvin; this is a song originally introduced by Shirley Temple) and "Stardust" get the Junior Parker vocals, and he is singing in a style distinctly different from his later R&B recordings. Here he seems to have been heavily influenced by Billy Eckstine.Eckstine is probably not as highly regarded today as he once was -- too florid to be a really successful jazz singer. But he was important in the history of modern jazz -- the first bandleader to give Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie a prominent role. And he influenced other jazz singers who are little remembered, like Kenny "Pancho" Hagood and -- had he not returned to his blues roots -- Junior Parker.

Eckstine was a little too florid, and his imitators a lot too florid -- especially when matched with Getz, who is certainly a romantic, but a drier, more modern romantic. He can unquestionably work with a singer -- "The Girl From Ipanema" proves that -- but he's not a good fit with Parker, or Parker is not a good fit for him. They say that along with the violin, the tenor saxophone is the instrument most alike in quality to the human voice, and on these standards, Getz sings. I love all of them -- even the Parker "Stardust," which grows on you, but mostly the instrumentals -- but perhaps "Too Marvelous for Words" more than any. "Too Marvelous" has a beautiful melody by Richard Whiting, and clever lyrics by Johnny Mercer, but...rather than hearing someone expend a whole lot of words to tell me that words won't do the job, I'd rather hear someone use words to do the job, as in "There's a Small Hotel" (Lorenz Hart) or "I've Got You Under My Skin" (Cole Porter).

Al Haig takes some terrific solos here too, but mostly it's Getz, Getz, Getz, and Getz at his youthful best.

Al Haig takes some terrific solos here too, but mostly it's Getz, Getz, Getz, and Getz at his youthful best.These also came out on 45 RPM -- rateyourmusic.com is a little vague on the 45s, but I'd guess maybe still in 1950, more likely in 1951 -- and on their 10 inch LP series -- along with the previous Getz session -- in 1951.

* In no biography or discography of Junior Parker that I've been able to find online -- and some of them are pretty complete -- is there a reference to this session with Stan Getz. All the ones I've seen have him first recording with Modern in 1952. But I'm fairly certain it's the same guy. If it turns out I'm wrong, and this is just a curious coincidence of names, I will eat crow. For now, I claim a discovery.

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records, Part 18: Coleman Hawkins

This finishes off 1949, Prestige's first year of operation, and a year that saw them still releasing exclusively on 78, though these early cuts would be re-released as they moved into the still-new LP field - and some on 45 RPM EPs. Many of these early records were originally recorded for European labels, then licensed to the fledgling Prestige for American distribution, giving Bob Weinstock the beginnings of a substantial catalog, and one hit: James Moody's "I'm in the Mood for Love."

December 21, 1949, saw Coleman Hawkins in Paris, with a group of ex-pats and French players, cutting a bunch of songs that never seem to have been released on any European label -- at least according to jazzdiscoorg -- and seem never to have received any exposure at all until years later, when they were finally released as part of the Prestige 7000 series. It may have originally been a radio broadcast.

Hawkins had lived the ex-pat life in Europe during the late 1930s, and throughout the 40s made several trips back across the Atlantic. Most notably with him on this date was Kenny Clarke, the bebop drumming pioneer who at this stage of his life was still back and forth to Paris, but would eventually (after a stint as the original drummer for the Modern Jazz Quartet) settle in Paris permanently. The other ex-pat was trombonist Nat Peck, who according to Wikipedia is still alive -- and someone should be interviewing him! He could almost have made my "living artists who played with Bird" series -- he did play with Dizzy Gillespie in 1953.

Of the French artists, Hubert Fol's bio can only be found on the German Wikipedia, but he played a lot with Django Reinhardt, as well as working with Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie and Howard McGhee on European tours. Pierre Michelot, who died in 2005, has an impressive resume with American ex-pats and touring musicians, but these two stand out for me. He was the bass player in a regular trio with Bud Powell and Kenny Clarke. And he worked with Miles Davis in creating the score for Ascenseur pour l'echafaud.

The session included six songs -- "Sih-Sah," "It's Only A Paper Moon," "Bean's Talking Again," "Bay-U-Bah," "I Surrender Dear," and "Sophisticated Lady." I only found "Sih-Sah" and "Bean's Talking Again"on Spotify, so those were the two I listened to most closely. They're billed as sextet records, but the other two horns play on very short opening and closing choruses, then stay out of the way. Which is a wise choice. Hawkins is strong, mellow, lyrical, beautiful. Both are ballads -- in fact. they're very similar.

You can find all or most of the cuts on YouTube thanks to a channel created by Heinz Becker. Here's "Sih-Sah":

December 21, 1949, saw Coleman Hawkins in Paris, with a group of ex-pats and French players, cutting a bunch of songs that never seem to have been released on any European label -- at least according to jazzdiscoorg -- and seem never to have received any exposure at all until years later, when they were finally released as part of the Prestige 7000 series. It may have originally been a radio broadcast.

|

| Coleman Hawkins |

Hawkins had lived the ex-pat life in Europe during the late 1930s, and throughout the 40s made several trips back across the Atlantic. Most notably with him on this date was Kenny Clarke, the bebop drumming pioneer who at this stage of his life was still back and forth to Paris, but would eventually (after a stint as the original drummer for the Modern Jazz Quartet) settle in Paris permanently. The other ex-pat was trombonist Nat Peck, who according to Wikipedia is still alive -- and someone should be interviewing him! He could almost have made my "living artists who played with Bird" series -- he did play with Dizzy Gillespie in 1953.

Of the French artists, Hubert Fol's bio can only be found on the German Wikipedia, but he played a lot with Django Reinhardt, as well as working with Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie and Howard McGhee on European tours. Pierre Michelot, who died in 2005, has an impressive resume with American ex-pats and touring musicians, but these two stand out for me. He was the bass player in a regular trio with Bud Powell and Kenny Clarke. And he worked with Miles Davis in creating the score for Ascenseur pour l'echafaud.

The session included six songs -- "Sih-Sah," "It's Only A Paper Moon," "Bean's Talking Again," "Bay-U-Bah," "I Surrender Dear," and "Sophisticated Lady." I only found "Sih-Sah" and "Bean's Talking Again"on Spotify, so those were the two I listened to most closely. They're billed as sextet records, but the other two horns play on very short opening and closing choruses, then stay out of the way. Which is a wise choice. Hawkins is strong, mellow, lyrical, beautiful. Both are ballads -- in fact. they're very similar.

You can find all or most of the cuts on YouTube thanks to a channel created by Heinz Becker. Here's "Sih-Sah":

Thursday, August 07, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records - Part 17: Sonny Stitt/Bud Powell

Interesting exchange of notes on Jazz Collector's blog:

Something I’ve long wondered is — if an artist without a regular working band came in to record, how were the sidemen chosen? At Blue Note, for example, did Alfred and Frank assemble the players, or would a guy with some pull like Dexter Gordon say, “Hey this is who I want to play with?” Could a name artist veto a sideman? Maybe the leader would come in with a couple of guys and then Lion would fill in the holes? It’s pretty clear that a lot of artists tended to record together, but overall it’s just something I’ve always wondered about.

First response:

My understanding from numerous jazz biographies, liner notes, etc is that the choice of sidemen was a combination of who the label knew; who the leader knew; and, often most importantly, who was in town on the days set for recording. Aside from steady bands (or pre-planned dates with written material), it was just catch-as-catch-can with the limited number of top guys who lived in town (or who happened to be in town for a while). I’m sure some folks with experience in the industry can provide more color (or correct my impression).

And another:

I would also bet that the label would pick sidemen that might bring some new tunes to the session, and that the label in turn might be able to extract publishing rights from those tunes. (Not that this ever happened of course)

And a third:

The sidemen story makes a lot of the great recordings seem like a stroke of dumb luck. Similarly, could some records have achieved legendary status in jazz history if so-and-so had been in town to play bass that day?

In the sixties, when three pretty good (all right, very good) guitarists got together, they were called a supergroup, and the recording was called a super session. In the jazz of the 40s and 50s, that happened all the time.

On December 11, 1949, Sonny Stitt came into the Prestige studios to record four tunes with a quartet, and the other members of the quartet were Curly Russell, Max Roach, and Bud Powell. Why these four, on that day? Hard to say. Bob Weinstock started Prestige because he had access to a lot of jazz players, because they hung out at his record store. Were they playing gigs in town? No way to find out that I've discovered. The New Yorker's Goings on About Town listings for that week include trad jazz clubs like Eddie Condon's and Jimmy Ryan's, but no club that featured modern jazz. Snobbery?

Racism? They just didn't get it? Lord knows, modern jazz was being played in New York. Bird land opened in 1949. 52nd Street had passed its prime, but there were still clubs there besides Jimmy Ryan's. Miles Davis had his Birth of the Cool nonet at the Royal Roost. The Famous Door was still around, although the Onyx had traded in jazz for strippers.

But for whatever reason, talk about a supergroup! And yes, this sort of thing happened all the time.

The four tunes are "All God's Chillun Got Rhythm," "Sonny Side," "Bud's Blues," and "Sunset." All are available on Spotify, either as the Sonny Stitt Quartet or the Bud Powell Quartet.

Sonny Stitt was 25 in 1949. He had met Charlie Parker six years earlier, and he was considered by many to be the player stylistically closest to Bird. It would be interesting -- for someone with a better than mine, and more musical knowledge -- to compare the

styles of the beboppers who spent their formative years playing in swing or rhythm and blues bands, and those who were virtually weaned on bebop.

These are four amazing cuts. If I had to pick a favorite moment, perhaps it's the trading back and forth of riffs between Stitt and Powell at the beginning of "Bud's Blues,"and the way Stitt takes it off from there, but all of it is wonderful. The composition of "Bud's Blues" is variously attributed to Bud Powell and Sonny Stitt - probably they both had a hand in it. It's become a jazz standard.

I suppose this could be considered, to use an Internet cliche, "I listen to the Prestige catalog so you don't have to," but you do have to. Listen to at least one cut from this session. "Bud's Blues" is a good one, but they're all good.

These sides were released on 78, on a 1951 10-inch release entitled Sonny Stitt and Bud Powell, and on a couple of different 7000-series LPs. including one called Sonny Stitt with Bud Powell and J. J. Johnson, incorporating the earlier J. J. Johnson's Boppers session.

Monday, August 04, 2014

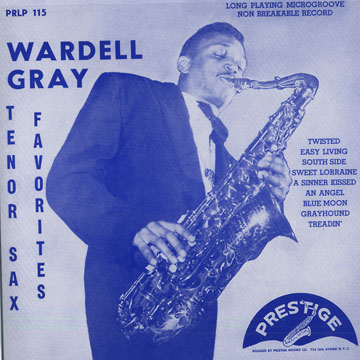

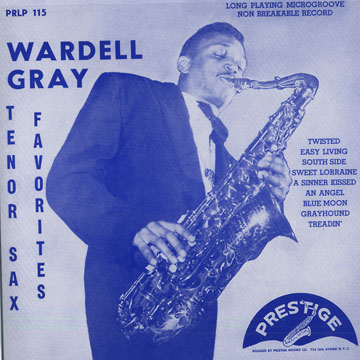

Listening to Prestige Records -- Part 16: Wardell Gray

Wardell Gray is known to aficionados of American literature as being one of the jazz musicians mentioned in Jack Kerouac's On The Road, along with George Shearing, Slim Gaillard, and Dexter Gordon, with whom Gray's name is forever linked as one of the great tenor sax pairings in jazz history.

He was known to younger musicians on the West Coast as a role model for music...and more:

After Bird, the skinny tenor man from the Billy Eckstine band was the musician most admired and respected by the younger players. He spoke quietly and articulately, admired the philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre and the politics of Henry Wallace, boosted the NAACP and advised fledgling jazzmen on music and life, particularly in regard to the futility of messing with drugs.

But he is most importantly known as a musician's musician, a man who could--and did--play with mastery in any style, from swing to rhythm and blues to be bebop. Benny Goodman, who at first rejected the new music, had his opinion changed by one man:

Goodman play bebop, and he abandoned the experiment), Wardell Gray was the first person he hired. In fact, Gray is most likely the only musician to have recorded with Benny Goodman, Count Basie and Charlie Parker.

Most famously, as a West Coast tenor player energized by Charlie Parker's ill-fated California tour, he engaged in a series of tenor battles that were captured on wax in "The Chase."

And perhaps second most famously, from his first session for Prestige, "Twisted," which became another vocalese hit, this one for Annie Ross, and later Bette Midler.

Gray was mostly known as a West Coast musician, but he did spend

enough time in New York to cut a few sessions for Prestige. This first

one, with as classic a bebop rhythm section as one could wish for,

includes "Sweet Lorraine," "Southside," "Twisted," and "Easy Living."

They capture everything that was great about Grey: lyricism, edginess,

tone, inventiveness. And this is the sort of album that I started this blog looking forward to finding: brilliant musicians, a tight group, inspired blowing, spontaneity.

Gray was mostly known as a West Coast musician, but he did spend

enough time in New York to cut a few sessions for Prestige. This first

one, with as classic a bebop rhythm section as one could wish for,

includes "Sweet Lorraine," "Southside," "Twisted," and "Easy Living."

They capture everything that was great about Grey: lyricism, edginess,

tone, inventiveness. And this is the sort of album that I started this blog looking forward to finding: brilliant musicians, a tight group, inspired blowing, spontaneity.

These four tunes were originally released by Prestige on their New Jazz 78 RPM series (817 and 828). and Southside/Sweet Lorraine also on a Prestige 78 (711). They were part of a 100-series 10-inch LP (Prestige PRLP 115--Wardell Gray Tenor Sax) and later on a couple of 7000-series albums, including the very complete Wardell Gray Memorial Album (PR 7343). All of Gray's work can be found on Spotify, and he's well represented on YouTube. Here's "Twisted."

And here is a segment from the documentary on Gray, Forgotten Tenor.

If Wardell Gray plays bop, it’s great. Because he’s wonderful.And when Goodman experimentally formed a bebop group (they played good music, but no one wanted to hear

Goodman play bebop, and he abandoned the experiment), Wardell Gray was the first person he hired. In fact, Gray is most likely the only musician to have recorded with Benny Goodman, Count Basie and Charlie Parker.

Most famously, as a West Coast tenor player energized by Charlie Parker's ill-fated California tour, he engaged in a series of tenor battles that were captured on wax in "The Chase."

And perhaps second most famously, from his first session for Prestige, "Twisted," which became another vocalese hit, this one for Annie Ross, and later Bette Midler.

Gray was mostly known as a West Coast musician, but he did spend

enough time in New York to cut a few sessions for Prestige. This first

one, with as classic a bebop rhythm section as one could wish for,

includes "Sweet Lorraine," "Southside," "Twisted," and "Easy Living."

They capture everything that was great about Grey: lyricism, edginess,

tone, inventiveness. And this is the sort of album that I started this blog looking forward to finding: brilliant musicians, a tight group, inspired blowing, spontaneity.

Gray was mostly known as a West Coast musician, but he did spend

enough time in New York to cut a few sessions for Prestige. This first

one, with as classic a bebop rhythm section as one could wish for,

includes "Sweet Lorraine," "Southside," "Twisted," and "Easy Living."

They capture everything that was great about Grey: lyricism, edginess,

tone, inventiveness. And this is the sort of album that I started this blog looking forward to finding: brilliant musicians, a tight group, inspired blowing, spontaneity. These four tunes were originally released by Prestige on their New Jazz 78 RPM series (817 and 828). and Southside/Sweet Lorraine also on a Prestige 78 (711). They were part of a 100-series 10-inch LP (Prestige PRLP 115--Wardell Gray Tenor Sax) and later on a couple of 7000-series albums, including the very complete Wardell Gray Memorial Album (PR 7343). All of Gray's work can be found on Spotify, and he's well represented on YouTube. Here's "Twisted."

And here is a segment from the documentary on Gray, Forgotten Tenor.

Sunday, August 03, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records - Part 15: James Moody

Well, it seems that for the nonce, we can't get away from Scandinavia. I'm moving on today from a Danish expat in New York to a New York expat in Sweden: James Moody.

But we're not leaving behind the bad bop puns -- or, for that matter, the boppified classics. One of Moody's cuts here is "Flight of the Bopple Bee."

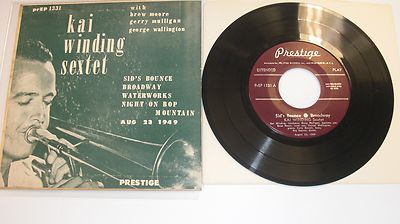

Stan Getz is forever linked with "Desafinado" and "Girl From Ipanema." Louis Armstrong? If you don't know anything else, you know "Hello Dolly" and "Wonderful World." Kai Winding may be most often remembered for his minor hit recording of "More (Theme from Mondo Cane)."

But possibly no other jazz musician, at least no other jazz musician with a lengthy and distinguished career, is as inextricably linked with one recording as James Moody and his classic "Moody's Mood for Love."

And that's interesting for a couple of reasons. First, his inextricable linkedness is not even due to his own recording, as good as it is -- it comes from the vocalese version by King Pleasure and Blossom Dearie (also on Prestige, so we'll get to that later). And for that matter, Moody passed up the pun on his name that would become iconic.

Second, and I hadn't realized this, the recording was made with an all-Swedish band of sidemen.

James Moody entered the studio in Stockholm on October 7, with a group he called James Moody's Swedish Crowns: Leppe Sundevall (tpt), Arne Domnerus (as), James Moody (ts), Per-Arne Croona (bar), Gosta Theselius (p), Yngve Akerberg (b), Anders Burman (d). They cut two songs -- "These Foolish Things" and "Out of Nowhere." "These Foolish Things" is a ballad, showcasing Moody's lyricism, and trying out a lot of ideas that would be developed and used again in "I'm in the Mood for Love."

On October 12, jazzdisco.com credits him with three different recording sessions, so either someone got the dates wrong, or quite possibly, it was a heavy work day for Mr. Moody. The first session is the James Moody Quintet, with Sundevall, Thore Swanerud (p). Yngve Akerberg (b), Jack Noren (d), and the numbers are "Flight of the Bopple Bee" and "I'm in the Mood for Bop" -- not the pun you were expecting, and not the song you were expecting, either. That comes later. "I'm in the Mood For Bop" is bebop, uptempo and bracing.

Then, still October 12, another session with the Swedish Crowns - same front line, Swanerud, Akerberg and Berman as rhythm section, and one with the James Moody Sextet (same without Theselius on tenor), and the songs are "Body and Soul," "I'm in the Mood for Love" (yes, that version), and "Lester Leaps In." All of this is a listening delight, but on "Lester Leaps In" you can hear the Swedes trying to be the Basie horn section and falling a little short.

A word on improvisation. It's not "just making it up as you go along," unless maybe you're Keith Jarrett. and it's not going to be entirely new every time. If Lester Young is playing a series of one-nighters with Count Basie, and he gets to the point where he stands up to play his solo on "Lester Leaps In," it's going to be more or less the same solo, with variations. So it's interesting to compare two totally different versions of the same song, done in the same recording session. "These Foolish Things" is closer to "I'm in the Mood for Love" than is "I'm in the Mood for Bop." Check it out. All are available on Spotify, as is yet another version from the same time period, "Moody's Mode."

"I'm in the Mood" became "Moody's Mood" when Eddie Jefferson wrote lyrics to it, and most famously when King Pleasure recorded it.

In an essay on rhyme, the poet Donald Justice points out that while rhyme is a great mnemonic, it's not enough to make something rhyme to make it memorable. It has to be true, too. "Red sky at night / Sailor's delight / Red sky at morning / Sailors take warning" has a catchy rhyme, but no one would remember it if it weren't also useful meteorological advice to sailors.

And such is also true for "Moody's Mood." Just setting lyrics to a jazz improvisation is no guarantee of immortality, It has to be the right tune, and "Moody's Mood" is. It is so lyrical, so melodic, so inventive. More about it later, since King Pleasure's version was also recorded for Prestige, but I will add that Moody himself did the vocal version many times later, including this -- one of my favorites -- with Tito Puente:

Here's James Moody talking about the famous "There I go, there I go, there I go..." opening -- just trying to learn how to find the notes on an unfamiliar alto sax.

And finally, just because it's so cool: From jazzcollector's website, an autographed copy of the original 78, which jazzcollector has no recollection of actually collecting, but there it is:

A week later, Moody came back and recorded two more sides with a quartet billed as James Moody and his Cool Cats: "Over the Rainbow" and "Blue and Moody."

Originally issued on the Swedish Metronome label, these sides were brought out by Prestige on 78 RPM, 45 RPM EP, and in various LP collections.

But we're not leaving behind the bad bop puns -- or, for that matter, the boppified classics. One of Moody's cuts here is "Flight of the Bopple Bee."

Stan Getz is forever linked with "Desafinado" and "Girl From Ipanema." Louis Armstrong? If you don't know anything else, you know "Hello Dolly" and "Wonderful World." Kai Winding may be most often remembered for his minor hit recording of "More (Theme from Mondo Cane)."

But possibly no other jazz musician, at least no other jazz musician with a lengthy and distinguished career, is as inextricably linked with one recording as James Moody and his classic "Moody's Mood for Love."

And that's interesting for a couple of reasons. First, his inextricable linkedness is not even due to his own recording, as good as it is -- it comes from the vocalese version by King Pleasure and Blossom Dearie (also on Prestige, so we'll get to that later). And for that matter, Moody passed up the pun on his name that would become iconic.

Second, and I hadn't realized this, the recording was made with an all-Swedish band of sidemen.

James Moody entered the studio in Stockholm on October 7, with a group he called James Moody's Swedish Crowns: Leppe Sundevall (tpt), Arne Domnerus (as), James Moody (ts), Per-Arne Croona (bar), Gosta Theselius (p), Yngve Akerberg (b), Anders Burman (d). They cut two songs -- "These Foolish Things" and "Out of Nowhere." "These Foolish Things" is a ballad, showcasing Moody's lyricism, and trying out a lot of ideas that would be developed and used again in "I'm in the Mood for Love."

On October 12, jazzdisco.com credits him with three different recording sessions, so either someone got the dates wrong, or quite possibly, it was a heavy work day for Mr. Moody. The first session is the James Moody Quintet, with Sundevall, Thore Swanerud (p). Yngve Akerberg (b), Jack Noren (d), and the numbers are "Flight of the Bopple Bee" and "I'm in the Mood for Bop" -- not the pun you were expecting, and not the song you were expecting, either. That comes later. "I'm in the Mood For Bop" is bebop, uptempo and bracing.

Then, still October 12, another session with the Swedish Crowns - same front line, Swanerud, Akerberg and Berman as rhythm section, and one with the James Moody Sextet (same without Theselius on tenor), and the songs are "Body and Soul," "I'm in the Mood for Love" (yes, that version), and "Lester Leaps In." All of this is a listening delight, but on "Lester Leaps In" you can hear the Swedes trying to be the Basie horn section and falling a little short.

A word on improvisation. It's not "just making it up as you go along," unless maybe you're Keith Jarrett. and it's not going to be entirely new every time. If Lester Young is playing a series of one-nighters with Count Basie, and he gets to the point where he stands up to play his solo on "Lester Leaps In," it's going to be more or less the same solo, with variations. So it's interesting to compare two totally different versions of the same song, done in the same recording session. "These Foolish Things" is closer to "I'm in the Mood for Love" than is "I'm in the Mood for Bop." Check it out. All are available on Spotify, as is yet another version from the same time period, "Moody's Mode."

"I'm in the Mood" became "Moody's Mood" when Eddie Jefferson wrote lyrics to it, and most famously when King Pleasure recorded it.

In an essay on rhyme, the poet Donald Justice points out that while rhyme is a great mnemonic, it's not enough to make something rhyme to make it memorable. It has to be true, too. "Red sky at night / Sailor's delight / Red sky at morning / Sailors take warning" has a catchy rhyme, but no one would remember it if it weren't also useful meteorological advice to sailors.

And such is also true for "Moody's Mood." Just setting lyrics to a jazz improvisation is no guarantee of immortality, It has to be the right tune, and "Moody's Mood" is. It is so lyrical, so melodic, so inventive. More about it later, since King Pleasure's version was also recorded for Prestige, but I will add that Moody himself did the vocal version many times later, including this -- one of my favorites -- with Tito Puente:

Here's James Moody talking about the famous "There I go, there I go, there I go..." opening -- just trying to learn how to find the notes on an unfamiliar alto sax.

And finally, just because it's so cool: From jazzcollector's website, an autographed copy of the original 78, which jazzcollector has no recollection of actually collecting, but there it is:

A week later, Moody came back and recorded two more sides with a quartet billed as James Moody and his Cool Cats: "Over the Rainbow" and "Blue and Moody."

Originally issued on the Swedish Metronome label, these sides were brought out by Prestige on 78 RPM, 45 RPM EP, and in various LP collections.

Saturday, August 02, 2014

Listening to Prestige Records - Part 14: Kai Winding

Some jazz musicians object to the word "jazz" as a name for their music, arguing that its origins as a slang word for sex trivialize the music it's attached to. But that same delicate sensibility doesn't seem to have extended to beboppers, if their propensity for making "bop" puns is any indication.

Take this Kai Winding session, for example, and "A Night on Bop Mountain." I'm not complaining, you understand. I love all these bad bop puns, and the bad puns on the names of the performers. And I love this boppified version of "A Night on Bald Mountain."

File this under Stuff I've never heard before. I really only knew Kai Winding from the J.J. and Kai recordings, so this is a chance to catch up on him earlier in his career. And file this under I Thought I Was Getting Away From Scandinavians For a While: Winding was Danish. Family emigrated to America when he was 12.

As noted before, this is a music lover blog, not a music critic blog and certainly not a music educator blog, but I'm always willing to learn something new, so here, from Barbara (BJBear) Major's Kai Winding site, a little music education:

The group here is the Kai Winding Sextette, featuring Brew Moore (ts), Gerry Mulligan (bs), George Wallington (p),Curly Russell (b), Max Roach (d), and the recording date is August 23, 1949. They may not have made a lot of waves - most Winding bios seem to skip over this part of his career, mentioning his work with big bands and then jumping to the J.J. and Kai group, but they made some impressive music.

In 1949, Gerry Mulligan had yet to lead his own group, and he was better known as an arranger, but this session doesn't sound Mulligan-arranged. It's a little harsher than I'd expect from Mulligan arrangements.

And this is interesting: a Gerry Mulligan discography lists a few 1949 sessions led by. Kai Winding and featuring Mulligan. One in April, which featured the same front line of Winding, Moore and Mulligan, and two thirds of the same rhythm section* -- Wallington and Russell, but with Kenny Clarke on drums, lists Mulligan as both baritone sax and arranger.The April recordings included "Godchild," later to be a part of the iconic Miles Davis Birth of the Cool sessions, also featuring Winding on trombone and Mulligan's arrangements.

However, the August recording lists him only as baritone sax player. His playing has a little harsher tone than the mellow sound he developed -- almost Lester Young on the baritone sax, which sounds pretty close to impossible when you say it, but because of Mulligan we take it for granted that a baritone sax can do that. On this set, in some places, his sax sounds more like the rhythm instrument that a baritone sax had mostly been -- and brilliant even at that -- but in a few solos he really stretches out.

Mulligan is certainly in the Jazz Hall of Fame. Kai Winding is probably in the fall of Jazz Lovers Know Who He Is, and Brew Moore in the hall of Really Serious Jazz Lovers Know Who He Is, but they all complement each other on these recordings.

"Sid's Bounce" and "A Night on Bop Mountain" were one New Jazz 78; "Broadway" and "Waterworks" were the other. Alternate takes of Broadway" and "Waterworks" made it onto the 45 RPM EP of the session, and onto PRLP 109, which brought Winding and J. J. Johnson together but separate.

* These guys seem to have played together a lot in 1949. Essentially the same group also recorded as the George Wallington Septet and the Brew Moore Septet.

Take this Kai Winding session, for example, and "A Night on Bop Mountain." I'm not complaining, you understand. I love all these bad bop puns, and the bad puns on the names of the performers. And I love this boppified version of "A Night on Bald Mountain."

File this under Stuff I've never heard before. I really only knew Kai Winding from the J.J. and Kai recordings, so this is a chance to catch up on him earlier in his career. And file this under I Thought I Was Getting Away From Scandinavians For a While: Winding was Danish. Family emigrated to America when he was 12.

As noted before, this is a music lover blog, not a music critic blog and certainly not a music educator blog, but I'm always willing to learn something new, so here, from Barbara (BJBear) Major's Kai Winding site, a little music education:

Kai was an "upstream" player and a form of Type IV in the Pivot System (mouthpiece low on the embouchure and airstream directed upwards into the mouthpiece). This produces a totally different tonal quality on the instrument than someone who is a "downstream" player.

The group here is the Kai Winding Sextette, featuring Brew Moore (ts), Gerry Mulligan (bs), George Wallington (p),Curly Russell (b), Max Roach (d), and the recording date is August 23, 1949. They may not have made a lot of waves - most Winding bios seem to skip over this part of his career, mentioning his work with big bands and then jumping to the J.J. and Kai group, but they made some impressive music.

In 1949, Gerry Mulligan had yet to lead his own group, and he was better known as an arranger, but this session doesn't sound Mulligan-arranged. It's a little harsher than I'd expect from Mulligan arrangements.

And this is interesting: a Gerry Mulligan discography lists a few 1949 sessions led by. Kai Winding and featuring Mulligan. One in April, which featured the same front line of Winding, Moore and Mulligan, and two thirds of the same rhythm section* -- Wallington and Russell, but with Kenny Clarke on drums, lists Mulligan as both baritone sax and arranger.The April recordings included "Godchild," later to be a part of the iconic Miles Davis Birth of the Cool sessions, also featuring Winding on trombone and Mulligan's arrangements.

However, the August recording lists him only as baritone sax player. His playing has a little harsher tone than the mellow sound he developed -- almost Lester Young on the baritone sax, which sounds pretty close to impossible when you say it, but because of Mulligan we take it for granted that a baritone sax can do that. On this set, in some places, his sax sounds more like the rhythm instrument that a baritone sax had mostly been -- and brilliant even at that -- but in a few solos he really stretches out.

Mulligan is certainly in the Jazz Hall of Fame. Kai Winding is probably in the fall of Jazz Lovers Know Who He Is, and Brew Moore in the hall of Really Serious Jazz Lovers Know Who He Is, but they all complement each other on these recordings.

"Sid's Bounce" and "A Night on Bop Mountain" were one New Jazz 78; "Broadway" and "Waterworks" were the other. Alternate takes of Broadway" and "Waterworks" made it onto the 45 RPM EP of the session, and onto PRLP 109, which brought Winding and J. J. Johnson together but separate.

* These guys seem to have played together a lot in 1949. Essentially the same group also recorded as the George Wallington Septet and the Brew Moore Septet.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)