Gene Ammons getting funky. Now, that makes sense. But...Gil Mellé?

Well, maybe funk for star people is a little different. Maybe it varies from asteroid to asteroid. Or maybe Mellé really is getting funky. Or maybe some combination of all of the above.

Mellé was getting ready to leave for Hollywood, and beyond: the Andromeda galaxy, and next stop...the Twilight Zone (or at least Rod Serling's Night Gallery). But meanwhile, he was still in New York, still in Hackensack, still doing a Friday with Rudy, and still working with some of the best jazz musicians New York had to offer.

Unfortunately, if he was planning to take this album with him as a keepsake to remember New York by, it was not to happen. The session was never released until many years later, as bonus tracks on the CD reissue of Gil's Guests. And because that CD threw together three different sessions with different musicians, these tracks are generally credited to Gil Mellé with Donald Byrd and Phil Woods, neither of whom actually appear on them.

But not to worry, there are plenty of great musicians, and guys who could get funky. Mellé follows his earlier formula of billing the session as a quartet plus guests, although actually the guests are more familiar to a Mellé session than half of the quartet. Art Farmer has appeared before as a Gil's Guest, and so has Hal McKusick (twice). Seldon Powell, primarily a rhythm and blues player, provides plenty of funk (and as jazz got funkier, he would be called on more and more for jazz sessions).

Teddy Charles provides the intergalactic balance, cool and clear and distant, particularly on "Golden Age."

Joe Cinderella is back as Mellé's right hand man, but the bass and drums are new--to Mellé, that is. Certainly not to jazz. And they are very much of this earth, rooted to the roots of jazz. They also aren't guys you'd grab up because they were just hanging around the studio, or because you'd seen their names on other Prestige sessions (although Shadow Wilson had done three, with Tadd Dameron, Earl Coleman and Sonny Stitt). Mellé must have given these selections a lot of thought, and reached out for players who had those roots. Wilson went back to the rhythm and blues of Lucky Millinder and Tiny Bradshaw, and the big band swing of Earl Hines, Lionel Hampton and Count Basie, although he was only 40 when he died, two years later, of a heroin overdose.

George Duvivier also went back to Lucky Millinder and Cab Calloway, although he made perhaps his

greatest mark with his 1953 recordings as a member of Bud Powell's trio. New to Prestige, he would be back with the label, and with funk, as the bassist on a number of Gene Ammons' recordings. It's hard to overestimate what he contributes here. He swings, he funks, he solos.

All the compositions are Mellé's, of course. He was looking very much in his own direction, and he wasn't going to find it improvising on the chord changes to "Stella by Starlight." He wasn't particularly an improviser either, and his future didn't lie in jazz, but he was drawn to jazz for a reason, and that included using gifted improvisers like Art Farmer.

Mellé was a very talented guy. He was a graphic artist, an inventor of electronic instruments, a composer. Jazz is a demanding mistress It's not an art that you dabble in, and a jack-of-all-trades isn't necessarily going to be able to pull it off. But Mellé did. He made a contribution to the music. And he discovered Rudy Van Gelder.

No picture of the album cover this time, since this session only became a years-later afterthought to a CD reissue. It deserved better.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

Tad Richards' odyssey through the catalog of Prestige Records:an unofficial and idiosyncratic history of jazz in the 50s and 60s. With occasional digressions.

Wednesday, August 31, 2016

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Listening to Prestige 203: Gene Ammons

1957 began as a year of Fridays with Rudy, and a year of all stars. The Prestige All Stars had kicked off the new year's celebration, and before 1957 was out, there would be 15 albums by one configuration or another of All Stars, two by the Art Taylor All Stars, and three more by the Prestige Jazz 4. If that sounds like a rather static year, it was anything but. As we know, the All Stars were never exactly the same aggregation, and as we also know, Prestige was capturing a core group of musicians who were evolving and growing over one of the great decades in jazz, as noted for innovation as it was for pleasure. And on top of that, there were to be plenty of new names, new sounds, new surprises.

This Gene Ammons album, although not labeled as such, was certainly an all star outing, and would later be repackaged as the Gene Ammons All Stars. Art Farmer, Jackie McLean and Kenny Burrell would make anyone's list of most important musicians of their era; Gene Ammons is probably more remembered as one of the good guys who made a contribution.

But Ammons made music that people liked to hear. This would be his 18th session for Prestige, either as leader, co-leader with Sonny Stitt, or sideman with Stitt. He would go on to record 45 more, and to be the only artist to continue to make new music for Prestige after the label's 1972 sale to Fantasy. So he must have been doing something right, and he was.

I don't completely understand why "Prestige All Stars" became what today would be called a brand in 1956-57. Was Weinstock trying out a theory that the label's name would sell more records than the individual artists? If so, Gene Ammons certainly would seem to be the exception.

Weinstock certainly knew what he had in Kenny Burrell, both as player and composer. He's responsible for the title cut on this album, "Funky." Funk would loom larger and larger as a musical concept in the next couple of decades, but it had always been around.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2188544-1268776791.jpeg.jpg)

Ammons generally had his own ideas of what to play. The tunes for a session were worked out between leader and producer, and Ammons quite likely chose "Stella by Starlight," probably with very little discussion. He loved standards, and Prestige artists did record a lot of standards. He may have caught Weinstock a little more by surprise with his other two selections. Record company owners in those days were very much aware of the value of publishing rights, which is why so many rock 'n roll and rhythm and blues artists got screwed. So here are two songs, "Pint Size" and "King Size," that have neither the name viability of a standard nor publishing rights in the family. They were written by Jimmy Mundy, a swing era veteran best known for his work as an arranger for Benny Goodman and Count Basie--and most recently as the composer of the score for a 1955 Broadway musical,The Vamp, which starred Carol Channing and ran for only 60 performances, but 60 performances on Broadway isn't nothing. Anyway, Ammons liked the tunes, and they sound good--although the phone book would sound good if these guys played it.

Ammons generally had his own ideas of what to play. The tunes for a session were worked out between leader and producer, and Ammons quite likely chose "Stella by Starlight," probably with very little discussion. He loved standards, and Prestige artists did record a lot of standards. He may have caught Weinstock a little more by surprise with his other two selections. Record company owners in those days were very much aware of the value of publishing rights, which is why so many rock 'n roll and rhythm and blues artists got screwed. So here are two songs, "Pint Size" and "King Size," that have neither the name viability of a standard nor publishing rights in the family. They were written by Jimmy Mundy, a swing era veteran best known for his work as an arranger for Benny Goodman and Count Basie--and most recently as the composer of the score for a 1955 Broadway musical,The Vamp, which starred Carol Channing and ran for only 60 performances, but 60 performances on Broadway isn't nothing. Anyway, Ammons liked the tunes, and they sound good--although the phone book would sound good if these guys played it.

I have a test for music called the Shopping List Test, which is, if you're driving a long listening to an album and thinking about what you need to pick up at Sam's Club, what suddenly seizes you out of your reverie and says "You've got to listen to this part right now!" This is not a test that particularly proves anything, because with music of this caliber it could be almost anything, but for me, yesterday afternoon, it was Mal Waldron on "Funky" and Art Farmer on "Stella." This is, of course, a meaningless test, because on the drive home it could be something completely different, but it makes me feel good.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

This Gene Ammons album, although not labeled as such, was certainly an all star outing, and would later be repackaged as the Gene Ammons All Stars. Art Farmer, Jackie McLean and Kenny Burrell would make anyone's list of most important musicians of their era; Gene Ammons is probably more remembered as one of the good guys who made a contribution.

But Ammons made music that people liked to hear. This would be his 18th session for Prestige, either as leader, co-leader with Sonny Stitt, or sideman with Stitt. He would go on to record 45 more, and to be the only artist to continue to make new music for Prestige after the label's 1972 sale to Fantasy. So he must have been doing something right, and he was.

I don't completely understand why "Prestige All Stars" became what today would be called a brand in 1956-57. Was Weinstock trying out a theory that the label's name would sell more records than the individual artists? If so, Gene Ammons certainly would seem to be the exception.

Weinstock certainly knew what he had in Kenny Burrell, both as player and composer. He's responsible for the title cut on this album, "Funky." Funk would loom larger and larger as a musical concept in the next couple of decades, but it had always been around.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2188544-1268776791.jpeg.jpg)

Ammons generally had his own ideas of what to play. The tunes for a session were worked out between leader and producer, and Ammons quite likely chose "Stella by Starlight," probably with very little discussion. He loved standards, and Prestige artists did record a lot of standards. He may have caught Weinstock a little more by surprise with his other two selections. Record company owners in those days were very much aware of the value of publishing rights, which is why so many rock 'n roll and rhythm and blues artists got screwed. So here are two songs, "Pint Size" and "King Size," that have neither the name viability of a standard nor publishing rights in the family. They were written by Jimmy Mundy, a swing era veteran best known for his work as an arranger for Benny Goodman and Count Basie--and most recently as the composer of the score for a 1955 Broadway musical,The Vamp, which starred Carol Channing and ran for only 60 performances, but 60 performances on Broadway isn't nothing. Anyway, Ammons liked the tunes, and they sound good--although the phone book would sound good if these guys played it.

Ammons generally had his own ideas of what to play. The tunes for a session were worked out between leader and producer, and Ammons quite likely chose "Stella by Starlight," probably with very little discussion. He loved standards, and Prestige artists did record a lot of standards. He may have caught Weinstock a little more by surprise with his other two selections. Record company owners in those days were very much aware of the value of publishing rights, which is why so many rock 'n roll and rhythm and blues artists got screwed. So here are two songs, "Pint Size" and "King Size," that have neither the name viability of a standard nor publishing rights in the family. They were written by Jimmy Mundy, a swing era veteran best known for his work as an arranger for Benny Goodman and Count Basie--and most recently as the composer of the score for a 1955 Broadway musical,The Vamp, which starred Carol Channing and ran for only 60 performances, but 60 performances on Broadway isn't nothing. Anyway, Ammons liked the tunes, and they sound good--although the phone book would sound good if these guys played it.I have a test for music called the Shopping List Test, which is, if you're driving a long listening to an album and thinking about what you need to pick up at Sam's Club, what suddenly seizes you out of your reverie and says "You've got to listen to this part right now!" This is not a test that particularly proves anything, because with music of this caliber it could be almost anything, but for me, yesterday afternoon, it was Mal Waldron on "Funky" and Art Farmer on "Stella." This is, of course, a meaningless test, because on the drive home it could be something completely different, but it makes me feel good.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

Sunday, August 28, 2016

Listening to Prestige 202: Prestige All-Stars

Starting in 1954, virtually every Prestige recording session bore the words "Rudy Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ." Later it would be Englewood Cliffs. But always Rudy Van Gelder, He's the one whom Miles Davis calls out to, when tension is rising between him and Thelonious Monk, and Monk is mockingly asking him when Miles wants it to play, "Hey Rudy, put this on the record, man – all of it!".

Rudy put all of it on the record...all that belonged. Because of his innovative engineering genius, jazz musicians sounded, on record, the way they really did sound. Jazz music, all music, owes him an incalculable debt. Goodbye, Rudy, who died this week at age 91, and the angels are finally getting their mikes adjusted right.

I don't really remember ever seeing a record by the Prestige All-Stars, perhaps because all of them were re-released later under the name of one or more of the musicians on the session. And maybe that was the idea all along--to get two releases out of each album. Bob Weinstock was known to have a good head for marketing.

The groups who recorded under that name fluctuated from album to album, and are generally described today as musicians who were under contract to Prestige, but surely Frank Foster couldn't have been? Foster is best known for his many years with the Basie band, and for assuming its leadership after the Count passed away, and by 1957, although he did make other records, he was a well-established Basie-ite, since 1953.

He had recorded for Prestige, with Monk in 1954 and as co-leader with Elmo Hope in 1955, and he would lead another session ten years later, but that doesn't exactly seem to make him a contract player. I'm not sure Tommy Flanagan really fits the picture, either, athough he had made a fairly solid debut in the New York recording scene for Prestige, accompanying Miles Davis, Phil Woods and Sonny Rollins (on the classic Saxophone Colossus album)

Still, who's complaining? Foster brings his Basie swing and his grasp of modernity, and Flanagan joins Kenny Burrell in another Detroit reunion. Actually, the whole session is a Detroit reunion, with Art Taylor the only New York outsider (although he's the only one to have a tune dedicated to him, Foster's "A.T."). Foster wasn't a native Detroiter, but he cut his musical teeth there.

Like the previous All-Stars a week earlier, this one was anchored by a Kenny Burrell composition that encompassed one whole album side. Foster took Jerome Richardson's place, doubling on flute and tenor sax, but unlike Richardson, he concentrated on tenor. He contributed one tune to the second half of the session, which also featured two originals by Donald Byrd.

All Day Long is the title of both the original Prestige All-Stars issue and the Kenny Burrell reissue. The original vinyl can also be found offered for sale as by the Frank Foster Sextet, perhaps because Foster's name is first on the lineup of musicians strung across the cover under the Verrazzano Narrows Bridge.

All Day Long is the title of both the original Prestige All-Stars issue and the Kenny Burrell reissue. The original vinyl can also be found offered for sale as by the Frank Foster Sextet, perhaps because Foster's name is first on the lineup of musicians strung across the cover under the Verrazzano Narrows Bridge.

And a subsequent CD release included the final Foster composition, "C.P.W.," left off the All-Stars and Burrell vinyl, but included in a Status low-budget compilation album.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

Rudy put all of it on the record...all that belonged. Because of his innovative engineering genius, jazz musicians sounded, on record, the way they really did sound. Jazz music, all music, owes him an incalculable debt. Goodbye, Rudy, who died this week at age 91, and the angels are finally getting their mikes adjusted right.

I don't really remember ever seeing a record by the Prestige All-Stars, perhaps because all of them were re-released later under the name of one or more of the musicians on the session. And maybe that was the idea all along--to get two releases out of each album. Bob Weinstock was known to have a good head for marketing.

The groups who recorded under that name fluctuated from album to album, and are generally described today as musicians who were under contract to Prestige, but surely Frank Foster couldn't have been? Foster is best known for his many years with the Basie band, and for assuming its leadership after the Count passed away, and by 1957, although he did make other records, he was a well-established Basie-ite, since 1953.

He had recorded for Prestige, with Monk in 1954 and as co-leader with Elmo Hope in 1955, and he would lead another session ten years later, but that doesn't exactly seem to make him a contract player. I'm not sure Tommy Flanagan really fits the picture, either, athough he had made a fairly solid debut in the New York recording scene for Prestige, accompanying Miles Davis, Phil Woods and Sonny Rollins (on the classic Saxophone Colossus album)

Still, who's complaining? Foster brings his Basie swing and his grasp of modernity, and Flanagan joins Kenny Burrell in another Detroit reunion. Actually, the whole session is a Detroit reunion, with Art Taylor the only New York outsider (although he's the only one to have a tune dedicated to him, Foster's "A.T."). Foster wasn't a native Detroiter, but he cut his musical teeth there.

Like the previous All-Stars a week earlier, this one was anchored by a Kenny Burrell composition that encompassed one whole album side. Foster took Jerome Richardson's place, doubling on flute and tenor sax, but unlike Richardson, he concentrated on tenor. He contributed one tune to the second half of the session, which also featured two originals by Donald Byrd.

All Day Long is the title of both the original Prestige All-Stars issue and the Kenny Burrell reissue. The original vinyl can also be found offered for sale as by the Frank Foster Sextet, perhaps because Foster's name is first on the lineup of musicians strung across the cover under the Verrazzano Narrows Bridge.

All Day Long is the title of both the original Prestige All-Stars issue and the Kenny Burrell reissue. The original vinyl can also be found offered for sale as by the Frank Foster Sextet, perhaps because Foster's name is first on the lineup of musicians strung across the cover under the Verrazzano Narrows Bridge.And a subsequent CD release included the final Foster composition, "C.P.W.," left off the All-Stars and Burrell vinyl, but included in a Status low-budget compilation album.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

Listening to Prestige 201: Wrapping up 1956

Here follows a blizzard of names, and I could have included more, if I'd used the entire rateyourmusic list for the year. But it gives you some idea of the richness and vitality of jazz in mid-decade.

Surely the biggest news from the Prestige label in 1956 was the wrapping up of the Miles Davis Contractual Marathon. He recorded fourteen songs in May, then twelve more in October, then Miles was off into the future, and one of the most storied careers in jazz, although Prestige would continue releasing albums from these sessions into 1961. The cuts were all first takes, and if Miles was rushing through them...well, he wasn't. The four albums that came out of the Contractual Marathon sessions, with John Coltrane and what became known as the First Great Quintet, remain some of Miles's most beloved work.

And they actually weren't all he did for Prestige that year. He led another quintet, with Sonny Rollins and Tommy Flanagan, in March.

And he left another legacy with Prestige, namely, his rhythm section. Bob Weinstock signed Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones to their own contract, and the trio, generally with Art Taylor on drums, would record nearly 30 albums for the label under Garland's name, and a bunch more backing up others.

Prestige was amassing one of the great rosters of rhythm section men in jazz history. In 1956 alone, Garland would play seven recording sessions, Paul Chambers ten, and Philly Joe Jones ten. And that was just the start of it. Mal Waldron appeared on six sessions, Doug Watkins on ten, Art Taylor on 14. So some cats were getting steady work, if they weren't exactly getting rich off it.

And others became very familiar with Hackensack. The summer of 1956 saw the Fridays with Rudy, as every weekend was preceded by one or even two Friday recording sessions. All in all, 48 sessions went down under the Prestige auspices, 41 of them in Rudy Van Gelder's studio

Jackie McLean recorded five sessions as leader, four more as sideman. Sonny Rollins did five as leader, one with Miles Davis. One of these was the only recording session to bring Rollins and John Coltrane together, on the epic "Tenor Madness." Like Miles, he moved on from Prestige after 1956. Donald Byrd was around a lot, with eight sessions as a sideman, one as a co-leader with Phil Woods, and two as a member of the Prestige All-Stars (one of these would be re-released as 2 Trumpets, leader credit shared by Byrd and Art Farmer). Hank Mobley also did two Prestige All-Stars sessions, three more as sideman and two as leader. Both Byrd and Mobley were to move over to Blue Note, where Mobley would stay for the rest of his recording career, whereas Byrd would eventually move on to new sounds with new labels. John Coltrane made the two Contractual Marathon sessions, and also played with Elmo Hope, Sonny Rollins, the Prestige All-Stars and Tadd Dameron.

Some were passing through. Jon Eardley made his fourth and last record for Prestige in January, then faded into obscurity for 20 years until he started recording again in Europe. George Wallington led a group with Donald Byrd and Phil Woods. He would make a few more records over the next year (one for New Jazz) before retiring to join the family's air conditioning business; it would be 30 years before he recorded again.

Tadd Dameron recorded far too little. His lasting reputation and legacy in jazz circles is testimony to how much we would have liked to get more of him, how lucky we were to get what we did. He went into the studio twice for Prestige in 1956, once with an octet, once with a quartet featuring John Coltrane. He would only make one more record after this, for Riverside in 1962. Bennie Green would make his last Prestige albums during the year, as would Elmo Hope, with one album as leader and two as sideman.

Gil Melle was actually quite active, cutting four sessions for Prestige in 1956, but he was shortly to take off for Hollywood and a career as composer of electronica and film scores.

Prestige recorded a few singers in 1956. Earl Coleman actually did go on recording, off and on, into the 1980s, but his career never really took off. At his best, he was very good. Barbara Lea's sessions for Prestige won her DownBeat's Critics' Award as Best New Singer of 1956, but she left singing for acting, to return to it years later. Blind Willie McTell was recorded in Atlanta in 1956, and his songs were later released on Prestige subsidiary Bluesville.

So, a good year for Bob Weinstock's label, as he continued to be at the hot epicenter of what was happening in jazz,

Clifford Brown appeared on one Prestige album along with Max Roach and Sonny Rollins -- it was the same group that had made such great records for EmArcy, but here under Rollins's name as leader. And Brown was to die that same year in a tragic auto accident that also claimed pianist Richie Powell.

Also departing the scene in 1956 were Art Tatum, Tommy Dorsey and Frankie Trumbauer.

Variety listed the top-selling jazz albums of the year:

Ella and Louis, Verve

Stan Kenton--Cuban Fire, Capitol

Jai and Kai plus 6, Columbia

Ella Fitzgerald sings the Cole Porter Songbook, Verve

Errol Garner--Concert by the Sea, Columbia

Kenton in Hi-Fi, Capitol

Chris Connor--He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not, Atlantic

Modern Jazz Quartet--Fontessa, Atlantic

Ella and Louis is undoubtedly still a jazz best-seller. So, probably, are Concert by the Sea, the MJQ album, and Ella singing Cole Porter, the first of her Songbook albums.

Other major releases for the year: Monk's Brilliant Corners, Mingus's Pithecanthropus Erectus, Rollins's Saxophone Colossus, Quincy Jones's This is How I Feel About Jazz, and of course, the obligation to Prestige having been filled, Miles's Round About Midnight for Columbia

Live releases from the Newport Jazz Festival included Dave Brubeck with Jay and Kai, and, most significantly, Duke Ellington. The classic Ellington at Newport was actually not the Duke's only live album from the festival: Check out the lesser-known Duke Ellington and the Buck Clayton All-Stars at Newport.

Metronome was DownBeat's chief competitor as a jazz magazine in the 40s and 50s, though it had actually been around since 1881, originally focusing on marching band music. Periodically, it would issue a Metronome Poll Winners LP, featuring a jam session of as many of the winners or near-winners as the staff (which included Leonard Feather) could get together. 1956 was their last dance, a 21-minute version of Charlie Parker's "Billie's Bounce," with solos by Thad Jones (trumpet), Lee Konitz (alto), Al Cohn and Zoot Sims (tenor), Tony Scott (clarinet), Serge Chaloff (baritone), Eddie Bert (trombone), Teddy Charles (vibes), Tal Farlow (guitar, Billy Taylor (piano), Charles Mingus (bass) and Art Blakey (drums). Metronome would cease publication in 1961.

A TV series hosted by Bobby Troup and called Stars of Jazz debuted on KABC-TV in Los Angeles. Its first show featured the Stan Getz Quartet and Kid Ory and his Creole Jazz Band

Here is my annual gripe about the crime against culture of not preserving all of DownBeat on digital archive. And as I write this, one cannot even access the readers' and critics' polls. Here's hoping that's a temporary glitch.

But here is the wonderfully bizarre RateYourMusic poll for the year, just including the jazz selections (#1 is Glenn Gould's Goldberg Variations). Don't forget these are 1956 releases, not recordings, which explains the presence of older sessions like the MJQ's Django.

2 Ellington at Newport

3 Pithecanthropus Erectus

The Charlie Mingus Jazz Workshop

4 Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Song Book

5 Lady Sings the Blues

Billie Holiday

6 Ella and Louis

9 Songs for Swingin' Lovers!

Frank Sinatra

11 Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Rodgers and Hart Song Book

12 Clifford Brown & Max Roach At Basin Street

14 The Jazz Messengers at the Cafe Bohemia, Volume 1

15 The Jazz Messengers

16 Sonny Rollins Plus 4

17 Tenor Madness

Sonny Rollins Quartet

20 Mingus at the Bohemia

21 Jazz Giant

Bud Powell

22 Concert by the Sea

23 Lennie Tristano

24 The Jazz Messengers at the Cafe Bohemia, Volume 2

26 Fontessa

28 Stan Getz Plays

33 Blue Serge

Serge Chaloff

34 Django

The Modern Jazz Quartet

35 Moondog

36 Moonlight in Vermont

Johnny Smith featuring Stan Getz

37 Jazz at Oberlin

The Dave Brubeck Quartet

38 The Unique Thelonious Monk

40 Here Is Phineas: The Piano Artistry of Phineas Newborn

42 Herbie Nichols Trio

43 Count Basie Swings - Joe Williams Sings

45 Whims of Chambers

Paul Chambers Sextet

46 The Boss of the Blues: Joe Turner Sings Kansas City Jazz

47 Ambassador Satch

Louis Armstrong

48 The Genius of Bud Powell

49 Russ Freeman / Chet Baker Quartet

50 Blossom Dearie

51 Miles

The New Miles Davis Quintet

52 Hi Fidelity Jam Session

Gene Ammons

54 Chris Connor

56 Modern Jazz Performances of Songs From My Fair Lady

Shelly Manne & His Friends

57 Jazz Workshop

George Russell

58 Jazz Immortal

Clifford Brown

59 Quintet / Sextet

Miles Davis and Milt Jackson

60 Lonely Girl

Julie London

61 Lights Out!

The Jackie McLean Quintet with Donald Byrd and Elmo Hope

62 Grand Encounter: 2° East / 3° West

John Lewis

63 Chamber Music of the New Jazz

Ahmad Jamal

64 Chet Baker Quartet Vol. 2

66 Work Time

Sonny Rollins

69 The Modern Jazz Sextet (Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Stitt, John Lewis, Percy Heath, Skeeter Best, Charlie Persip)

73 The Jazz Giants '56

Lester Young, Teddy Wilson, Roy Eldridge, Vic Dickenson, Jo Jones, Freddie Green & Gene Ramey

75 The Kenny Drew Trio

76 Kenton in Hi-Fi

77 Collectors' Items

Miles Davis

78 The Oscar Peterson Trio at the Stratford Shakespearean Festival

79 Calendar Girl

Julie London

80 Sarah Vaughan in the Land of Hi-Fi

I always get carried away with this list because it's so exhaustive. It goes on through #1200. Anyway, other jazz artists included farther down the list are Kenny Burrell, Rosemary Clooney, June Christy, Mel Tormé With Marty Paich, Jimmy Smith, Harry Edison, Gene Krupa, Tito Puente, Jimmy Giuffre, Tal Farlow, Teddy Charles, Elmo Hope, Chico Hamilton, the High Society soundtrack, Thad Jones, Gene Ammons, Cannonball Adderley, Hampton Hawes, Art Tatum, Curtis Counce, Sonny Criss, Warne Marsh, Gil Mellé, Dexter Gordon, Herb Ellis, Vince Guaraldi, Art Pepper, Art Farmer, Dinah Washington, George Shearing, Tadd Dameron, Phil Woods, Alain Goraguer, Jon Eardley, Betty Carter & Ray Bryant, Maxine Sullivan, Shelly Manne, Gene Quill, Al Cohn & Zoot Sims, Coleman Hawkins with Billy Byers, Kid Ory, Buddy Rich, Cal Tjader, Shorty Rogers, Tommy Dorsey, Gerry Mulligan, James Moody, Jimmy Cleveland, Betty Roché, Lee Konitz, Kenny Clarke, Jackie McLean, Bill Perkins, Carl Perkins, Randy Weston, Toni Harper, Carmen McRae, Meade Lux Lewis, Herbie Mann, Billy Bauer, Johnny Hodges, George Van Eps, Benny Goodman, Lennie Niehaus, Ernie Henry, Lee Wiley, Jack Teagarden, Doug Watkins, Cecil Payne, Annie Ross, Roy Eldridge, Mundell Lowe, Dorothy Carless, Jutta Hipp, Bud Shank, Muggsy Spanier, Allen Eager & Brew Moore, Jane Fielding, Bob Brookmeyer, Charlie Mariano, Sam Most, Chico Hamilton, Barbara Lea, Joe Wilder, Hank Jones, Billy Taylor, Candido, Bennie Green, Jimmy Raney, Eddie Costa & Vinnie Burke, Buddy Collette, George Wallington, Tony Scott...and that's just from the first 400. The list actually encompasses 1200 albums, with Teddy Wilson on the penultimate page. In other words, if you wanted to do a blog just listening to 1956, you'd have your work cut out for you.

The New Yorker continued to favor Dixieland and trad jazz spots. The Five Spot opened in 1956, with Cecil Taylor leading the house trio, but it gets no mention. Still, they're beginning to do a little better. And New York was New York, the Big Apple. It was where musicians came, and you were always going to be able to hear great music. 52nd Street was mostly gone, except for the Dixieland at Jimmy Ryan's, but there was a surprising amount of jazz in midtown. Birdland was a relatively recent arrival on the venerable street of jazz, and a powerhouse, featuring Count Basie, Chris Connor, the MJQ, and Phineas Newborn.

The Metropole, on Times Square, always had an amazing retinue of traditional players. Louis Armstrong was at Basin Street at 51st and Broadway. Also Cameo, on E. 53rd, alternated Barbara Carroll and Teddy Wilson on piano, and a block north, The Embers had a quartet of Tyree Glenn, Jo Jones, Tommy Potter and Dick Katz. Childs Paramount, which can't have lasted very long but must have been some sort of joint venture between the Childs restaurant chain and the Paramount Hotel, had a heck of a New Year's Eve show with Buck Clayton Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge and PeeWee Russell leading an all star lineup.

In Greenwich Village, the Village Vanguard was already an institution, but not always a jazz institution. To usher in the new year, however, they presented Abbey Lincoln. The Cafe Bohemia on Barrow Street, home to some classic live albums, alternated quintets led by Max Roach and Lester Young, and would have been a great place to spend New Year's Eve.

Surely the biggest news from the Prestige label in 1956 was the wrapping up of the Miles Davis Contractual Marathon. He recorded fourteen songs in May, then twelve more in October, then Miles was off into the future, and one of the most storied careers in jazz, although Prestige would continue releasing albums from these sessions into 1961. The cuts were all first takes, and if Miles was rushing through them...well, he wasn't. The four albums that came out of the Contractual Marathon sessions, with John Coltrane and what became known as the First Great Quintet, remain some of Miles's most beloved work.

And they actually weren't all he did for Prestige that year. He led another quintet, with Sonny Rollins and Tommy Flanagan, in March.

And he left another legacy with Prestige, namely, his rhythm section. Bob Weinstock signed Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones to their own contract, and the trio, generally with Art Taylor on drums, would record nearly 30 albums for the label under Garland's name, and a bunch more backing up others.

Prestige was amassing one of the great rosters of rhythm section men in jazz history. In 1956 alone, Garland would play seven recording sessions, Paul Chambers ten, and Philly Joe Jones ten. And that was just the start of it. Mal Waldron appeared on six sessions, Doug Watkins on ten, Art Taylor on 14. So some cats were getting steady work, if they weren't exactly getting rich off it.

And others became very familiar with Hackensack. The summer of 1956 saw the Fridays with Rudy, as every weekend was preceded by one or even two Friday recording sessions. All in all, 48 sessions went down under the Prestige auspices, 41 of them in Rudy Van Gelder's studio

Jackie McLean recorded five sessions as leader, four more as sideman. Sonny Rollins did five as leader, one with Miles Davis. One of these was the only recording session to bring Rollins and John Coltrane together, on the epic "Tenor Madness." Like Miles, he moved on from Prestige after 1956. Donald Byrd was around a lot, with eight sessions as a sideman, one as a co-leader with Phil Woods, and two as a member of the Prestige All-Stars (one of these would be re-released as 2 Trumpets, leader credit shared by Byrd and Art Farmer). Hank Mobley also did two Prestige All-Stars sessions, three more as sideman and two as leader. Both Byrd and Mobley were to move over to Blue Note, where Mobley would stay for the rest of his recording career, whereas Byrd would eventually move on to new sounds with new labels. John Coltrane made the two Contractual Marathon sessions, and also played with Elmo Hope, Sonny Rollins, the Prestige All-Stars and Tadd Dameron.

Some were passing through. Jon Eardley made his fourth and last record for Prestige in January, then faded into obscurity for 20 years until he started recording again in Europe. George Wallington led a group with Donald Byrd and Phil Woods. He would make a few more records over the next year (one for New Jazz) before retiring to join the family's air conditioning business; it would be 30 years before he recorded again.

Tadd Dameron recorded far too little. His lasting reputation and legacy in jazz circles is testimony to how much we would have liked to get more of him, how lucky we were to get what we did. He went into the studio twice for Prestige in 1956, once with an octet, once with a quartet featuring John Coltrane. He would only make one more record after this, for Riverside in 1962. Bennie Green would make his last Prestige albums during the year, as would Elmo Hope, with one album as leader and two as sideman.

Gil Melle was actually quite active, cutting four sessions for Prestige in 1956, but he was shortly to take off for Hollywood and a career as composer of electronica and film scores.

Prestige recorded a few singers in 1956. Earl Coleman actually did go on recording, off and on, into the 1980s, but his career never really took off. At his best, he was very good. Barbara Lea's sessions for Prestige won her DownBeat's Critics' Award as Best New Singer of 1956, but she left singing for acting, to return to it years later. Blind Willie McTell was recorded in Atlanta in 1956, and his songs were later released on Prestige subsidiary Bluesville.

So, a good year for Bob Weinstock's label, as he continued to be at the hot epicenter of what was happening in jazz,

Clifford Brown appeared on one Prestige album along with Max Roach and Sonny Rollins -- it was the same group that had made such great records for EmArcy, but here under Rollins's name as leader. And Brown was to die that same year in a tragic auto accident that also claimed pianist Richie Powell.

Also departing the scene in 1956 were Art Tatum, Tommy Dorsey and Frankie Trumbauer.

Variety listed the top-selling jazz albums of the year:

Ella and Louis, Verve

Stan Kenton--Cuban Fire, Capitol

Jai and Kai plus 6, Columbia

Ella Fitzgerald sings the Cole Porter Songbook, Verve

Errol Garner--Concert by the Sea, Columbia

Kenton in Hi-Fi, Capitol

Chris Connor--He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not, Atlantic

Modern Jazz Quartet--Fontessa, Atlantic

Ella and Louis is undoubtedly still a jazz best-seller. So, probably, are Concert by the Sea, the MJQ album, and Ella singing Cole Porter, the first of her Songbook albums.

Other major releases for the year: Monk's Brilliant Corners, Mingus's Pithecanthropus Erectus, Rollins's Saxophone Colossus, Quincy Jones's This is How I Feel About Jazz, and of course, the obligation to Prestige having been filled, Miles's Round About Midnight for Columbia

Live releases from the Newport Jazz Festival included Dave Brubeck with Jay and Kai, and, most significantly, Duke Ellington. The classic Ellington at Newport was actually not the Duke's only live album from the festival: Check out the lesser-known Duke Ellington and the Buck Clayton All-Stars at Newport.

Metronome was DownBeat's chief competitor as a jazz magazine in the 40s and 50s, though it had actually been around since 1881, originally focusing on marching band music. Periodically, it would issue a Metronome Poll Winners LP, featuring a jam session of as many of the winners or near-winners as the staff (which included Leonard Feather) could get together. 1956 was their last dance, a 21-minute version of Charlie Parker's "Billie's Bounce," with solos by Thad Jones (trumpet), Lee Konitz (alto), Al Cohn and Zoot Sims (tenor), Tony Scott (clarinet), Serge Chaloff (baritone), Eddie Bert (trombone), Teddy Charles (vibes), Tal Farlow (guitar, Billy Taylor (piano), Charles Mingus (bass) and Art Blakey (drums). Metronome would cease publication in 1961.

A TV series hosted by Bobby Troup and called Stars of Jazz debuted on KABC-TV in Los Angeles. Its first show featured the Stan Getz Quartet and Kid Ory and his Creole Jazz Band

Here is my annual gripe about the crime against culture of not preserving all of DownBeat on digital archive. And as I write this, one cannot even access the readers' and critics' polls. Here's hoping that's a temporary glitch.

But here is the wonderfully bizarre RateYourMusic poll for the year, just including the jazz selections (#1 is Glenn Gould's Goldberg Variations). Don't forget these are 1956 releases, not recordings, which explains the presence of older sessions like the MJQ's Django.

2 Ellington at Newport

3 Pithecanthropus Erectus

The Charlie Mingus Jazz Workshop

4 Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Song Book

5 Lady Sings the Blues

Billie Holiday

6 Ella and Louis

9 Songs for Swingin' Lovers!

Frank Sinatra

11 Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Rodgers and Hart Song Book

12 Clifford Brown & Max Roach At Basin Street

14 The Jazz Messengers at the Cafe Bohemia, Volume 1

15 The Jazz Messengers

16 Sonny Rollins Plus 4

17 Tenor Madness

Sonny Rollins Quartet

20 Mingus at the Bohemia

21 Jazz Giant

Bud Powell

22 Concert by the Sea

23 Lennie Tristano

24 The Jazz Messengers at the Cafe Bohemia, Volume 2

26 Fontessa

28 Stan Getz Plays

33 Blue Serge

Serge Chaloff

34 Django

The Modern Jazz Quartet

35 Moondog

36 Moonlight in Vermont

Johnny Smith featuring Stan Getz

37 Jazz at Oberlin

The Dave Brubeck Quartet

38 The Unique Thelonious Monk

40 Here Is Phineas: The Piano Artistry of Phineas Newborn

42 Herbie Nichols Trio

43 Count Basie Swings - Joe Williams Sings

45 Whims of Chambers

Paul Chambers Sextet

46 The Boss of the Blues: Joe Turner Sings Kansas City Jazz

47 Ambassador Satch

Louis Armstrong

48 The Genius of Bud Powell

49 Russ Freeman / Chet Baker Quartet

50 Blossom Dearie

51 Miles

The New Miles Davis Quintet

52 Hi Fidelity Jam Session

Gene Ammons

54 Chris Connor

56 Modern Jazz Performances of Songs From My Fair Lady

Shelly Manne & His Friends

57 Jazz Workshop

George Russell

58 Jazz Immortal

Clifford Brown

59 Quintet / Sextet

Miles Davis and Milt Jackson

60 Lonely Girl

Julie London

61 Lights Out!

The Jackie McLean Quintet with Donald Byrd and Elmo Hope

62 Grand Encounter: 2° East / 3° West

John Lewis

63 Chamber Music of the New Jazz

Ahmad Jamal

64 Chet Baker Quartet Vol. 2

66 Work Time

Sonny Rollins

69 The Modern Jazz Sextet (Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Stitt, John Lewis, Percy Heath, Skeeter Best, Charlie Persip)

73 The Jazz Giants '56

Lester Young, Teddy Wilson, Roy Eldridge, Vic Dickenson, Jo Jones, Freddie Green & Gene Ramey

75 The Kenny Drew Trio

76 Kenton in Hi-Fi

77 Collectors' Items

Miles Davis

78 The Oscar Peterson Trio at the Stratford Shakespearean Festival

79 Calendar Girl

Julie London

80 Sarah Vaughan in the Land of Hi-Fi

I always get carried away with this list because it's so exhaustive. It goes on through #1200. Anyway, other jazz artists included farther down the list are Kenny Burrell, Rosemary Clooney, June Christy, Mel Tormé With Marty Paich, Jimmy Smith, Harry Edison, Gene Krupa, Tito Puente, Jimmy Giuffre, Tal Farlow, Teddy Charles, Elmo Hope, Chico Hamilton, the High Society soundtrack, Thad Jones, Gene Ammons, Cannonball Adderley, Hampton Hawes, Art Tatum, Curtis Counce, Sonny Criss, Warne Marsh, Gil Mellé, Dexter Gordon, Herb Ellis, Vince Guaraldi, Art Pepper, Art Farmer, Dinah Washington, George Shearing, Tadd Dameron, Phil Woods, Alain Goraguer, Jon Eardley, Betty Carter & Ray Bryant, Maxine Sullivan, Shelly Manne, Gene Quill, Al Cohn & Zoot Sims, Coleman Hawkins with Billy Byers, Kid Ory, Buddy Rich, Cal Tjader, Shorty Rogers, Tommy Dorsey, Gerry Mulligan, James Moody, Jimmy Cleveland, Betty Roché, Lee Konitz, Kenny Clarke, Jackie McLean, Bill Perkins, Carl Perkins, Randy Weston, Toni Harper, Carmen McRae, Meade Lux Lewis, Herbie Mann, Billy Bauer, Johnny Hodges, George Van Eps, Benny Goodman, Lennie Niehaus, Ernie Henry, Lee Wiley, Jack Teagarden, Doug Watkins, Cecil Payne, Annie Ross, Roy Eldridge, Mundell Lowe, Dorothy Carless, Jutta Hipp, Bud Shank, Muggsy Spanier, Allen Eager & Brew Moore, Jane Fielding, Bob Brookmeyer, Charlie Mariano, Sam Most, Chico Hamilton, Barbara Lea, Joe Wilder, Hank Jones, Billy Taylor, Candido, Bennie Green, Jimmy Raney, Eddie Costa & Vinnie Burke, Buddy Collette, George Wallington, Tony Scott...and that's just from the first 400. The list actually encompasses 1200 albums, with Teddy Wilson on the penultimate page. In other words, if you wanted to do a blog just listening to 1956, you'd have your work cut out for you.

The New Yorker continued to favor Dixieland and trad jazz spots. The Five Spot opened in 1956, with Cecil Taylor leading the house trio, but it gets no mention. Still, they're beginning to do a little better. And New York was New York, the Big Apple. It was where musicians came, and you were always going to be able to hear great music. 52nd Street was mostly gone, except for the Dixieland at Jimmy Ryan's, but there was a surprising amount of jazz in midtown. Birdland was a relatively recent arrival on the venerable street of jazz, and a powerhouse, featuring Count Basie, Chris Connor, the MJQ, and Phineas Newborn.

The Metropole, on Times Square, always had an amazing retinue of traditional players. Louis Armstrong was at Basin Street at 51st and Broadway. Also Cameo, on E. 53rd, alternated Barbara Carroll and Teddy Wilson on piano, and a block north, The Embers had a quartet of Tyree Glenn, Jo Jones, Tommy Potter and Dick Katz. Childs Paramount, which can't have lasted very long but must have been some sort of joint venture between the Childs restaurant chain and the Paramount Hotel, had a heck of a New Year's Eve show with Buck Clayton Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge and PeeWee Russell leading an all star lineup.

In Greenwich Village, the Village Vanguard was already an institution, but not always a jazz institution. To usher in the new year, however, they presented Abbey Lincoln. The Cafe Bohemia on Barrow Street, home to some classic live albums, alternated quintets led by Max Roach and Lester Young, and would have been a great place to spend New Year's Eve.

On to 1957.

Monday, August 22, 2016

Listening to Prestige 200: Moondog

In perfect symmetry, I'm finishing up 1956 with blog entry 200. In perfect asymmetry, I'm finishing up 1956 with something completely different.

Growing up in this era, even though I didn't live in New York City and visited it only sporadically, I knew about Moondog. Everyone did. The giant bearded street musician, who wore a viking helmet and carried a spear He was a New York character, one who stood out even in a city full of eight million stories and at least a few thousand eccentrics.

As a devotee and somewhat serious student of rock and roll (I was turned down for a faculty grant in 1965 to do a study of doo-wop, surely the first such request they had ever gotten), I knew that Alan Freed had called himself Moondog when he began playing rhythm and blues music on the radio in Cleveland, but had had to change it when he arrived in New York, home of the real and original Moondog. That's when Freed began calling the music he played rock 'n roll.

But I never knew anything about Moondog's music.

Alan Freed did. He had taken the name from an early 78 RPM recording called "Moondog Symphony," one of Moondog's first.

It was a curious choice in every way. It was a symphony of percussion: Drums, maracas, claves, gourds, hollow log, Chinese block and cymbals. All Moondog. And there wasn't much in the way of multitracking for a self-made 78 in 1949, so he invented his own system, working back and forth between two tape recorders.

It was curious that Freed found it at all. The record only sold a few hundred copies.

It was perhaps even more curious that he liked it, and used it as the theme song for a radio show playing black rhythm and blues for white teenagers. One might have expected that a swing-era cat like Freed would have chosen a Gene Krupa recording as theme music, but Moondog's was as far from swing as could be imagined. He called it snaketime music: "a slithery rhythm, in times that are not ordinary ... I'm not gonna die in 4/4 time."

I knew that Freed had had to stop using Moondog's name. I didn't know that he had taken Freed to court, and that the case had gone all the way to the New York State Supreme Court. Moondog himself later said that the courts would most likely have ruled against a Viking-accoutred street person, had not Benny Goodman and Arturo Toscanini testified to his importance as a composer.

I didn't know lots of other things. That his real name was Louis Hardin, that he was related to the old Western gunslinger John Wesley Hardin, that he had gone blind at age 16, that he had married a socially prominent older woman in Arkansas but had left her to come to New York, live on the street and make music.

Mostly, I didn't know his music. I had never listened to it until encountering it as the next step in my

Prestige journey. And a surprising step it was. My general policy has been not to look ahead, preferring to take the music as it comes. So where did Moondog fit into Bob Weinstock's universe?

It's hard to say. There don't seem to exist any interviews with Weinstock where he discusses this particular choice, but actually there's more of Moondog on Prestige than anywhere else, and these recordings capture an important part of his oeuvre. He had actually recorded for a jazz label once before--Woody Herman's short-lived Mars label.

The music amazed me. I'm a fan of the avant-garde music of the mid- and late-twentieth century: Terry Riley, LaMonte Young, Pauline Oliveros, Gavin Bryars. And Moondog is one of the finest avant-garde composers I have ever heard.

As other avant-garde composers have done, and as was certainly appropriate for a street musician, he used a lot of ambient sound. There's the Queen Elizabeth in the harbor, its "deep-throated whistle" blending with, and extended by, Moondog's bamboo pipe. There's the horn of a tugboat, as eerily melodic as the songs of the humpbacked whale that would become popular a generation or so later, blended into an almost, but not exactly orchestral blend of instruments. And the sounds move away from the street, too. Moondog was married for a second time in 1952, to a Japanese-American woman named Suzuko Whiteing, so he wasn't entirely homeless, though he still lived, by choice, mostly on the streets. "Lullabye" combines the cries of their six-week-old baby with Suzuko singing (or chanting) a lullabye in what I guess is Japanese, and music by a sextet composed in something like a pentatonic Japanese scale.

Moondog also experimented with a wide variety of instruments, many of his own invention. He was particularly drawn to the oo, a triangular-shaped 25-string harp struck with a clava. He also created a variety of percussion instruments, and percussion played an important part in his compositions. His music was always rhythmic, but rhythmic in his own way, with the slithery snaketime rhythms. On Oo Debut," a short piece (as were most of his compositions), he simultaneously played the oo and the trimba, a triangular drum that is still used by musicians today.

The "and other" musicians that are mentioned in the session notes are also varied. Sometimes he worked alone, sometimes with a quintet or sextet. Most of the compositions are quite short, "Surf Session" being the exception at nearly seven minutes.

The first of these sessions was released by Prestige as Moondog, the second as More Moondog. More Moondog was largely recorded by Tony Schwartz, who was known as a sound archivist, and whose collections of street sounds were released by Folkways. One would have thought of Folkways as a more likely home for Moondog, but his work was much admired by modern jazz icons like Charlie Parker and Charles Mingus, and PRestige is the richer for it.

The first album sold respectably--enough for Moondog to buy property upstate near Owego, which became his retreat from the city. Probably its sales were due to its novelty value, as there isn't much of a market for serious avant garde music. The second two -- there would be one more -- did not do so well.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

Growing up in this era, even though I didn't live in New York City and visited it only sporadically, I knew about Moondog. Everyone did. The giant bearded street musician, who wore a viking helmet and carried a spear He was a New York character, one who stood out even in a city full of eight million stories and at least a few thousand eccentrics.

As a devotee and somewhat serious student of rock and roll (I was turned down for a faculty grant in 1965 to do a study of doo-wop, surely the first such request they had ever gotten), I knew that Alan Freed had called himself Moondog when he began playing rhythm and blues music on the radio in Cleveland, but had had to change it when he arrived in New York, home of the real and original Moondog. That's when Freed began calling the music he played rock 'n roll.

But I never knew anything about Moondog's music.

Alan Freed did. He had taken the name from an early 78 RPM recording called "Moondog Symphony," one of Moondog's first.

It was a curious choice in every way. It was a symphony of percussion: Drums, maracas, claves, gourds, hollow log, Chinese block and cymbals. All Moondog. And there wasn't much in the way of multitracking for a self-made 78 in 1949, so he invented his own system, working back and forth between two tape recorders.

It was curious that Freed found it at all. The record only sold a few hundred copies.

It was perhaps even more curious that he liked it, and used it as the theme song for a radio show playing black rhythm and blues for white teenagers. One might have expected that a swing-era cat like Freed would have chosen a Gene Krupa recording as theme music, but Moondog's was as far from swing as could be imagined. He called it snaketime music: "a slithery rhythm, in times that are not ordinary ... I'm not gonna die in 4/4 time."

I knew that Freed had had to stop using Moondog's name. I didn't know that he had taken Freed to court, and that the case had gone all the way to the New York State Supreme Court. Moondog himself later said that the courts would most likely have ruled against a Viking-accoutred street person, had not Benny Goodman and Arturo Toscanini testified to his importance as a composer.

I didn't know lots of other things. That his real name was Louis Hardin, that he was related to the old Western gunslinger John Wesley Hardin, that he had gone blind at age 16, that he had married a socially prominent older woman in Arkansas but had left her to come to New York, live on the street and make music.

Mostly, I didn't know his music. I had never listened to it until encountering it as the next step in my

Prestige journey. And a surprising step it was. My general policy has been not to look ahead, preferring to take the music as it comes. So where did Moondog fit into Bob Weinstock's universe?

It's hard to say. There don't seem to exist any interviews with Weinstock where he discusses this particular choice, but actually there's more of Moondog on Prestige than anywhere else, and these recordings capture an important part of his oeuvre. He had actually recorded for a jazz label once before--Woody Herman's short-lived Mars label.

The music amazed me. I'm a fan of the avant-garde music of the mid- and late-twentieth century: Terry Riley, LaMonte Young, Pauline Oliveros, Gavin Bryars. And Moondog is one of the finest avant-garde composers I have ever heard.

As other avant-garde composers have done, and as was certainly appropriate for a street musician, he used a lot of ambient sound. There's the Queen Elizabeth in the harbor, its "deep-throated whistle" blending with, and extended by, Moondog's bamboo pipe. There's the horn of a tugboat, as eerily melodic as the songs of the humpbacked whale that would become popular a generation or so later, blended into an almost, but not exactly orchestral blend of instruments. And the sounds move away from the street, too. Moondog was married for a second time in 1952, to a Japanese-American woman named Suzuko Whiteing, so he wasn't entirely homeless, though he still lived, by choice, mostly on the streets. "Lullabye" combines the cries of their six-week-old baby with Suzuko singing (or chanting) a lullabye in what I guess is Japanese, and music by a sextet composed in something like a pentatonic Japanese scale.

|

| The trimba |

Moondog also experimented with a wide variety of instruments, many of his own invention. He was particularly drawn to the oo, a triangular-shaped 25-string harp struck with a clava. He also created a variety of percussion instruments, and percussion played an important part in his compositions. His music was always rhythmic, but rhythmic in his own way, with the slithery snaketime rhythms. On Oo Debut," a short piece (as were most of his compositions), he simultaneously played the oo and the trimba, a triangular drum that is still used by musicians today.

The "and other" musicians that are mentioned in the session notes are also varied. Sometimes he worked alone, sometimes with a quintet or sextet. Most of the compositions are quite short, "Surf Session" being the exception at nearly seven minutes.

The first album sold respectably--enough for Moondog to buy property upstate near Owego, which became his retreat from the city. Probably its sales were due to its novelty value, as there isn't much of a market for serious avant garde music. The second two -- there would be one more -- did not do so well.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

Listening to Prestige 199: The Prestige All-Stars

This is the familiar -- and magnificent -- core of the Prestige All-Stars, with two new additions, and what a difference they make! The veterans are Donald Byrd, Hank Mobley, and the rhythm section of Mal Waldron, Doug Watkins and Art Taylor. The new additions are Jerome Richardson and Kenny Burrell, and with them, Prestige takes a step forward into what will become the jazz sound of the Sixties.

A lot of this has to do with the instrumentation. Richardson was proficient on pretty much anything that could be played with a reed, and a few instruments that couldn't. On this album he doubles on flute and tenor sax, but it's the flute that really stands out.

These aren't the first instance of flute and guitar playing a major role on a Prestige recording session. Herbie Mann, Sam Most and Bobby Jaspar all recorded for Prestige. The label's most prominent guitarist was probably Jimmy Raney, who recorded with his own group, and played with Bob Brookmeyer and Teddy Charles (and who would later do an album with Kenny Burrell for Prestige). Billy Bauer also contributed some memorable sessions with Lee Konitz.

But this is different, and different all around. The instrumentation makes it different, but that's not all. It's a sound that's really looking toward the future. That future would be irrevocably ushered in the following year, with a recording made in 1949, but buried by Capitol Records until it finally got its LP release in 1957: the Miles Davis nonet's Birth of the Cool.

This session still has all the passionate heat of bop, but the flute is an instrument that lends itself to the cool sound, and jazz is forever evolving. It's interesting that this session was recorded under the Prestige All-Stars banner, but fitting. The Prestige veterans were not standing still, either. Donald Byd in particular, was still at the cusp of a career that would see him in more than one vanguard.

The opening salvo of "All Night Long" is by Art Taylor, and creates a different rhythmic pattern from any we've heard before, which leads right into a Kenny Burrell solo, followed by Richardson on flute. By this time, we're well into the LP era, and long cuts are common, but "All Night Long" is long even by 1956 standards, checking at 17:11, and giving all the All-Stars plenty of room to develop. Which they do. Every solo on it is wonderful. Burrell and Richardson stand out, but it's hard to take the record off without marveling at Mal Waldron's solo.

"All Night Long" is a Burrell original, and Burrell was hitting the scene hard. He was born and raised

in the jazz hotbed of Detroit, and went to college there, at Wayne State, where he studied music composition and theory, and founded an organization called the New World Music Society, which included fellow Detroiters Pepper Adams, Yusef Lateef, Donald Byrd and Elvin Jones.

He graduated in 1955 and joined the Oscar Peterson Trio, a gig for which his early admiration for guitarist Oscar Moore of the Nat "King" Cole Trio and Johnny Moore's Three Blazers had well prepared him.

He then headed for New York where his reputation preceded him. As well it might have. As a 19-year-old, he had already recorded with a group including Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane in Detroit, but had resisted the invitation to tour with Dizzy. opting for college and music theory. He hit New York right after graduation, and not only did he find work right away, he found a leader's role right away, recording three albums under his own name for Blue Note (one of his later Blue Note albums, Midnight Blue, was such a favorite of Alfred Lion's that it was one of the albums he was buried with). He also joined the house band at Minton's Playhouse (Minton's is best known as the birthplace of bebop in the 1940s, but it continued to be a jazz proving ground through the 50sand 60s), which was led at the time by Jerome Richardson.

The first Blue Note album featured all original Burrell compositions, showing that those years at Wayne State paid off.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-831406-1254766358.jpeg.jpg) The rest of this album is given over to two other world class composers, Mal Waldron and Hank Mobley. I particularly loved "Boo-Lu" and the irresistible riff it's built around. One (or two) more numbers were included on the session, but not on the album. One or two because on the session notes, they're listed as a medley: "Body and Soul" and "Tune Up." Which is a cool and unusual medley -- a standard from the Great American Songbook and a jazz standard by Miles Davis. But when they were included as bonus tracks on a CD release of the album, they became separate tunes. "Body and Soul" was also released as part of a compilation album of various artists doing the Eyton/Green/Heyman/Sour composition, on the Prestige subsidiary label Status, which the invaluable London Jazz Collector describes as:

The rest of this album is given over to two other world class composers, Mal Waldron and Hank Mobley. I particularly loved "Boo-Lu" and the irresistible riff it's built around. One (or two) more numbers were included on the session, but not on the album. One or two because on the session notes, they're listed as a medley: "Body and Soul" and "Tune Up." Which is a cool and unusual medley -- a standard from the Great American Songbook and a jazz standard by Miles Davis. But when they were included as bonus tracks on a CD release of the album, they became separate tunes. "Body and Soul" was also released as part of a compilation album of various artists doing the Eyton/Green/Heyman/Sour composition, on the Prestige subsidiary label Status, which the invaluable London Jazz Collector describes as:

The original release was called All Night Long and credited to the Prestige All-Stars, but then, when subsequent Burrell session became All Day Long, the Night version was rereleased as a Kenny Burrell album.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

A lot of this has to do with the instrumentation. Richardson was proficient on pretty much anything that could be played with a reed, and a few instruments that couldn't. On this album he doubles on flute and tenor sax, but it's the flute that really stands out.

These aren't the first instance of flute and guitar playing a major role on a Prestige recording session. Herbie Mann, Sam Most and Bobby Jaspar all recorded for Prestige. The label's most prominent guitarist was probably Jimmy Raney, who recorded with his own group, and played with Bob Brookmeyer and Teddy Charles (and who would later do an album with Kenny Burrell for Prestige). Billy Bauer also contributed some memorable sessions with Lee Konitz.

But this is different, and different all around. The instrumentation makes it different, but that's not all. It's a sound that's really looking toward the future. That future would be irrevocably ushered in the following year, with a recording made in 1949, but buried by Capitol Records until it finally got its LP release in 1957: the Miles Davis nonet's Birth of the Cool.

This session still has all the passionate heat of bop, but the flute is an instrument that lends itself to the cool sound, and jazz is forever evolving. It's interesting that this session was recorded under the Prestige All-Stars banner, but fitting. The Prestige veterans were not standing still, either. Donald Byd in particular, was still at the cusp of a career that would see him in more than one vanguard.

The opening salvo of "All Night Long" is by Art Taylor, and creates a different rhythmic pattern from any we've heard before, which leads right into a Kenny Burrell solo, followed by Richardson on flute. By this time, we're well into the LP era, and long cuts are common, but "All Night Long" is long even by 1956 standards, checking at 17:11, and giving all the All-Stars plenty of room to develop. Which they do. Every solo on it is wonderful. Burrell and Richardson stand out, but it's hard to take the record off without marveling at Mal Waldron's solo.

"All Night Long" is a Burrell original, and Burrell was hitting the scene hard. He was born and raised

in the jazz hotbed of Detroit, and went to college there, at Wayne State, where he studied music composition and theory, and founded an organization called the New World Music Society, which included fellow Detroiters Pepper Adams, Yusef Lateef, Donald Byrd and Elvin Jones.

He graduated in 1955 and joined the Oscar Peterson Trio, a gig for which his early admiration for guitarist Oscar Moore of the Nat "King" Cole Trio and Johnny Moore's Three Blazers had well prepared him.

He then headed for New York where his reputation preceded him. As well it might have. As a 19-year-old, he had already recorded with a group including Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane in Detroit, but had resisted the invitation to tour with Dizzy. opting for college and music theory. He hit New York right after graduation, and not only did he find work right away, he found a leader's role right away, recording three albums under his own name for Blue Note (one of his later Blue Note albums, Midnight Blue, was such a favorite of Alfred Lion's that it was one of the albums he was buried with). He also joined the house band at Minton's Playhouse (Minton's is best known as the birthplace of bebop in the 1940s, but it continued to be a jazz proving ground through the 50sand 60s), which was led at the time by Jerome Richardson.

The first Blue Note album featured all original Burrell compositions, showing that those years at Wayne State paid off.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-831406-1254766358.jpeg.jpg) The rest of this album is given over to two other world class composers, Mal Waldron and Hank Mobley. I particularly loved "Boo-Lu" and the irresistible riff it's built around. One (or two) more numbers were included on the session, but not on the album. One or two because on the session notes, they're listed as a medley: "Body and Soul" and "Tune Up." Which is a cool and unusual medley -- a standard from the Great American Songbook and a jazz standard by Miles Davis. But when they were included as bonus tracks on a CD release of the album, they became separate tunes. "Body and Soul" was also released as part of a compilation album of various artists doing the Eyton/Green/Heyman/Sour composition, on the Prestige subsidiary label Status, which the invaluable London Jazz Collector describes as:

The rest of this album is given over to two other world class composers, Mal Waldron and Hank Mobley. I particularly loved "Boo-Lu" and the irresistible riff it's built around. One (or two) more numbers were included on the session, but not on the album. One or two because on the session notes, they're listed as a medley: "Body and Soul" and "Tune Up." Which is a cool and unusual medley -- a standard from the Great American Songbook and a jazz standard by Miles Davis. But when they were included as bonus tracks on a CD release of the album, they became separate tunes. "Body and Soul" was also released as part of a compilation album of various artists doing the Eyton/Green/Heyman/Sour composition, on the Prestige subsidiary label Status, which the invaluable London Jazz Collector describes as:Difficult to see what was budget apart from saving on ink, providing minimal information saved nothing, but made it look budget. Working in Marketing in the Seventies, the big fear was always “cannibalisation”. You wanted all the sales you could get at the premium price, and extra sales at the budget price, without losing the one to the other. Extra effort was incurred to make things look less attractive. More marketing genius from Weinstock.

The original release was called All Night Long and credited to the Prestige All-Stars, but then, when subsequent Burrell session became All Day Long, the Night version was rereleased as a Kenny Burrell album.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

Sunday, August 14, 2016

Listening to Prestige 198: Red Garland

This is what happened after Jackie and his pal left to down a couple of cold ones and talk about what they could have done better (hint: not much). The rest of the afternoon was given over to Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Art Taylor: once again, not a full album's worth of music, so the session would be issued piecemeal.

Garland had just recorded Frank Loesser's "If I Were a Bell" three months earlier as part of the final Miles Davis contractual marathon series. He opens his version of it with the same memorable chime-like intro, so I went back to listen to that version.

Garland actually had relatively little solo space on the Miles recording--when you have Miles and Trane, there's not a lot of space left oer--and what there was, was mostly duets with Chambers, so here he really has room to stretch out and show what he can do, which is a lot. Fascinating to listen to both versions.

"Willow Weep for Me" is a great standard both for singers and instrumentalists, and both have a debt

to Ann Ronell, who wrote words and music. You might guess that "Willow Weep for Me" is Ronell's best known song, and it sort of is, but that depends on who you talk to. She also wrote "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf." A protege of George Gershwin, Ronell was one of the first women to break into the boys' club of popular songwriting. Along with Loesser, she was one of the few composers who wrote their own lyrics.

Like the McLean session, this was broken up and mixed with a later date. "If I Were a Bell" and "I Know Why" came out on Red Garland's Piano, "Willow Weep for Me" and "What Can I Say Dear" on Groovy, another one of my purchases in my very early days of jazz collecting.

Like the McLean session, this was broken up and mixed with a later date. "If I Were a Bell" and "I Know Why" came out on Red Garland's Piano, "Willow Weep for Me" and "What Can I Say Dear" on Groovy, another one of my purchases in my very early days of jazz collecting.Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

Friday, August 05, 2016

Listening to Prestige 197: Jackie McLean

Jackie McLean was by now a veteran of Prestige sessions, but not quite as much of a veteran as you'd think. Yes, he goes back to the early days--1951, and the notorious Miles Davis "Dig" session (notorious for Miles having appropriated the composition as his own). But after that, a long hiatus, not just from Prestige, but from recording altogether. There was a live recording of a couple of nights at Birdland, and session a few days later for Blue Note, all in 1952 but not, I believe, released till much later. Then nothing at all until 1955, and it's hard to say why not. He was battling addiction, but lots of musicians were fighting this fight at the time, and many of them still recorded. When Jackie did come back into the studio in 1955, with Miles again, he was only used on two tunes of a four-tune session, and Miles said later that Jackie was so high, he could barely play. Miles never used him again.

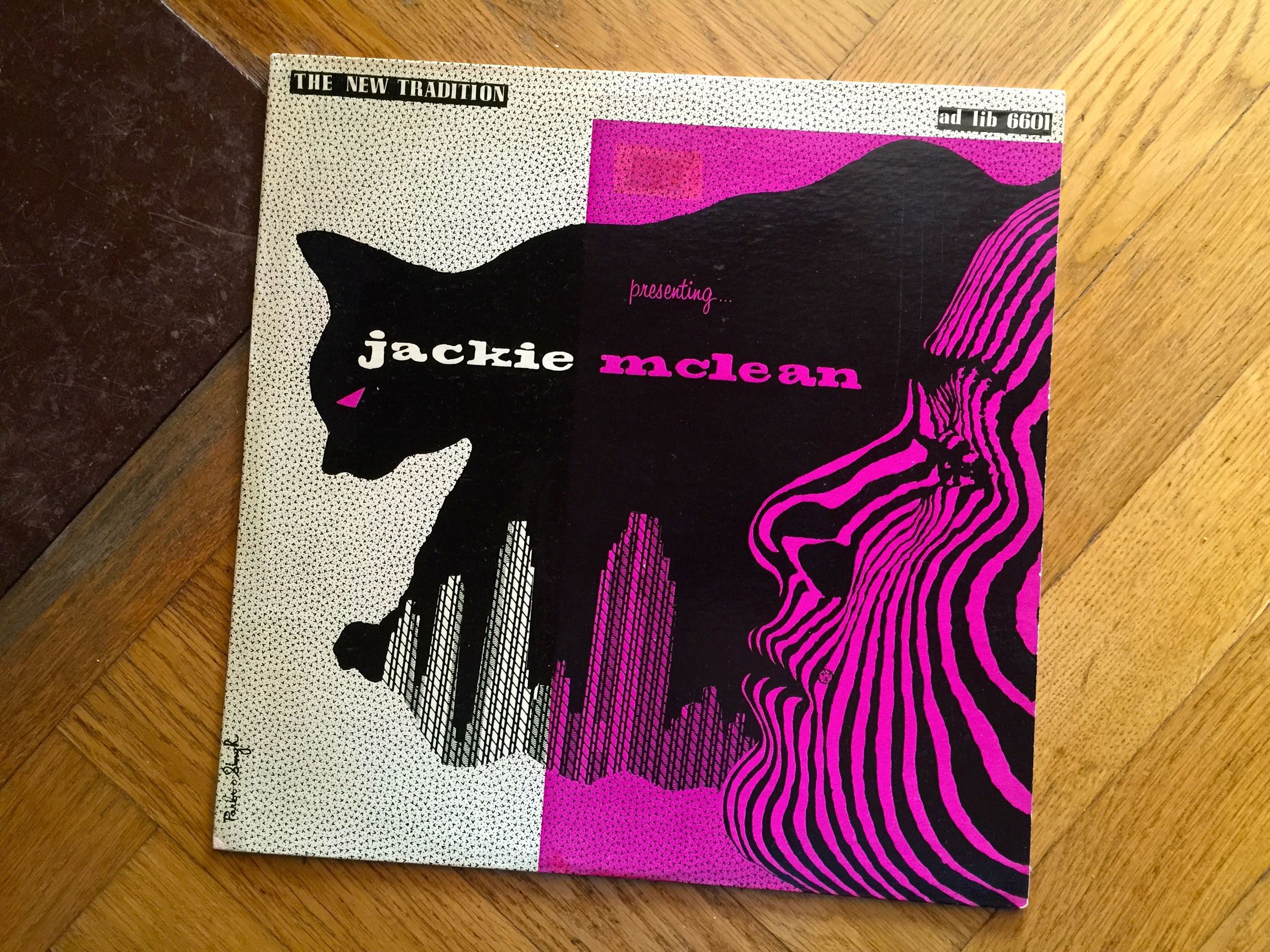

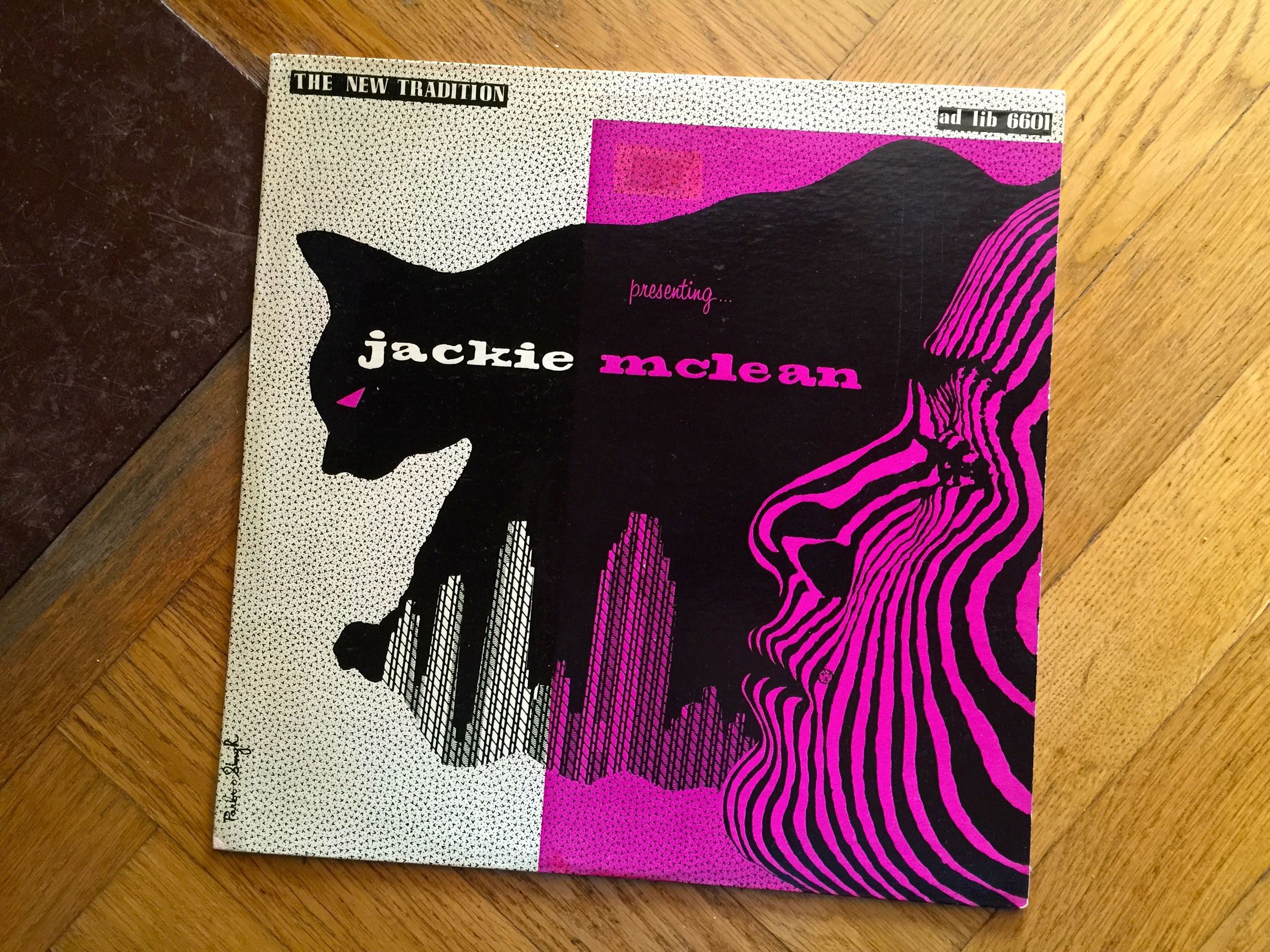

He played on a couple more sessions in '55--one with George Wallington, the other under his own leadership, Both were released on tiny labels: the Wallington live album on Progressive, the McLean Sextet album on Ad Lib. This one, according to the Rare Vinyl Jazz Collector (and aren't you glad such people exist), is "possibly the rarest of all the jazz collectibles out there." So since, like the ivory-billed woodpecker, it may never actually be seen in the wild, here's a picture of the album cover. I don't know who did the art, but it's a gem.

He played on a couple more sessions in '55--one with George Wallington, the other under his own leadership, Both were released on tiny labels: the Wallington live album on Progressive, the McLean Sextet album on Ad Lib. This one, according to the Rare Vinyl Jazz Collector (and aren't you glad such people exist), is "possibly the rarest of all the jazz collectibles out there." So since, like the ivory-billed woodpecker, it may never actually be seen in the wild, here's a picture of the album cover. I don't know who did the art, but it's a gem.

So, veteran or no, 1956 was really his debut year as a jazz force. He recorded for Prestige, Atlantic (with Mingus) and Columbia (with Blakey). By August, he was considered enough of a star that Bill Hardman was introduced on his first recording session as ""Jackie's Pal."

Jackie's pal is back with him for this abbreviated session, along with Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Art Taylor, who would take center stage as a trio for the rest of the afternoon. They do two standards and an original.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2937631-1308161023.jpeg.jpg) It's wonderful listening. The interplay between the two pals is intricate and yet straightforward, especially on "McLean's Scene." And this rhythm section continues to reward, every time out. Some great solos by Red Garland and Art Taylor, but it's Paul Chambers who takes your breath away. You expect a bass solo to come somewhere in the middle of a quintet piece, but on "Gone With the Wind" Chambers is the penultimate solo, right before McLean and and the restatement of the head.

It's wonderful listening. The interplay between the two pals is intricate and yet straightforward, especially on "McLean's Scene." And this rhythm section continues to reward, every time out. Some great solos by Red Garland and Art Taylor, but it's Paul Chambers who takes your breath away. You expect a bass solo to come somewhere in the middle of a quintet piece, but on "Gone With the Wind" Chambers is the penultimate solo, right before McLean and and the restatement of the head.

You expect a piano vamp to begin a jazz quartet or quintet number--sometimes an extended vamp that becomes the head and an improvised solo. On "Mean to Me," though the first notes one hears are Garland's, Paul Chambers steps in and takes over that job. Cool.

Because this was an abbreviated session, it had to wait for LP release. It was combined with a 1957 McLean session with a different lineup, and released in 1959 on New Jazz.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

He played on a couple more sessions in '55--one with George Wallington, the other under his own leadership, Both were released on tiny labels: the Wallington live album on Progressive, the McLean Sextet album on Ad Lib. This one, according to the Rare Vinyl Jazz Collector (and aren't you glad such people exist), is "possibly the rarest of all the jazz collectibles out there." So since, like the ivory-billed woodpecker, it may never actually be seen in the wild, here's a picture of the album cover. I don't know who did the art, but it's a gem.

He played on a couple more sessions in '55--one with George Wallington, the other under his own leadership, Both were released on tiny labels: the Wallington live album on Progressive, the McLean Sextet album on Ad Lib. This one, according to the Rare Vinyl Jazz Collector (and aren't you glad such people exist), is "possibly the rarest of all the jazz collectibles out there." So since, like the ivory-billed woodpecker, it may never actually be seen in the wild, here's a picture of the album cover. I don't know who did the art, but it's a gem.So, veteran or no, 1956 was really his debut year as a jazz force. He recorded for Prestige, Atlantic (with Mingus) and Columbia (with Blakey). By August, he was considered enough of a star that Bill Hardman was introduced on his first recording session as ""Jackie's Pal."

Jackie's pal is back with him for this abbreviated session, along with Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Art Taylor, who would take center stage as a trio for the rest of the afternoon. They do two standards and an original.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2937631-1308161023.jpeg.jpg) It's wonderful listening. The interplay between the two pals is intricate and yet straightforward, especially on "McLean's Scene." And this rhythm section continues to reward, every time out. Some great solos by Red Garland and Art Taylor, but it's Paul Chambers who takes your breath away. You expect a bass solo to come somewhere in the middle of a quintet piece, but on "Gone With the Wind" Chambers is the penultimate solo, right before McLean and and the restatement of the head.