Nothing, as it turns out. Talk about four brothers! These are four of the all-time greats on the instrument that became the heart and soul of jazz and rhythm and blues of the 40s and 50s.

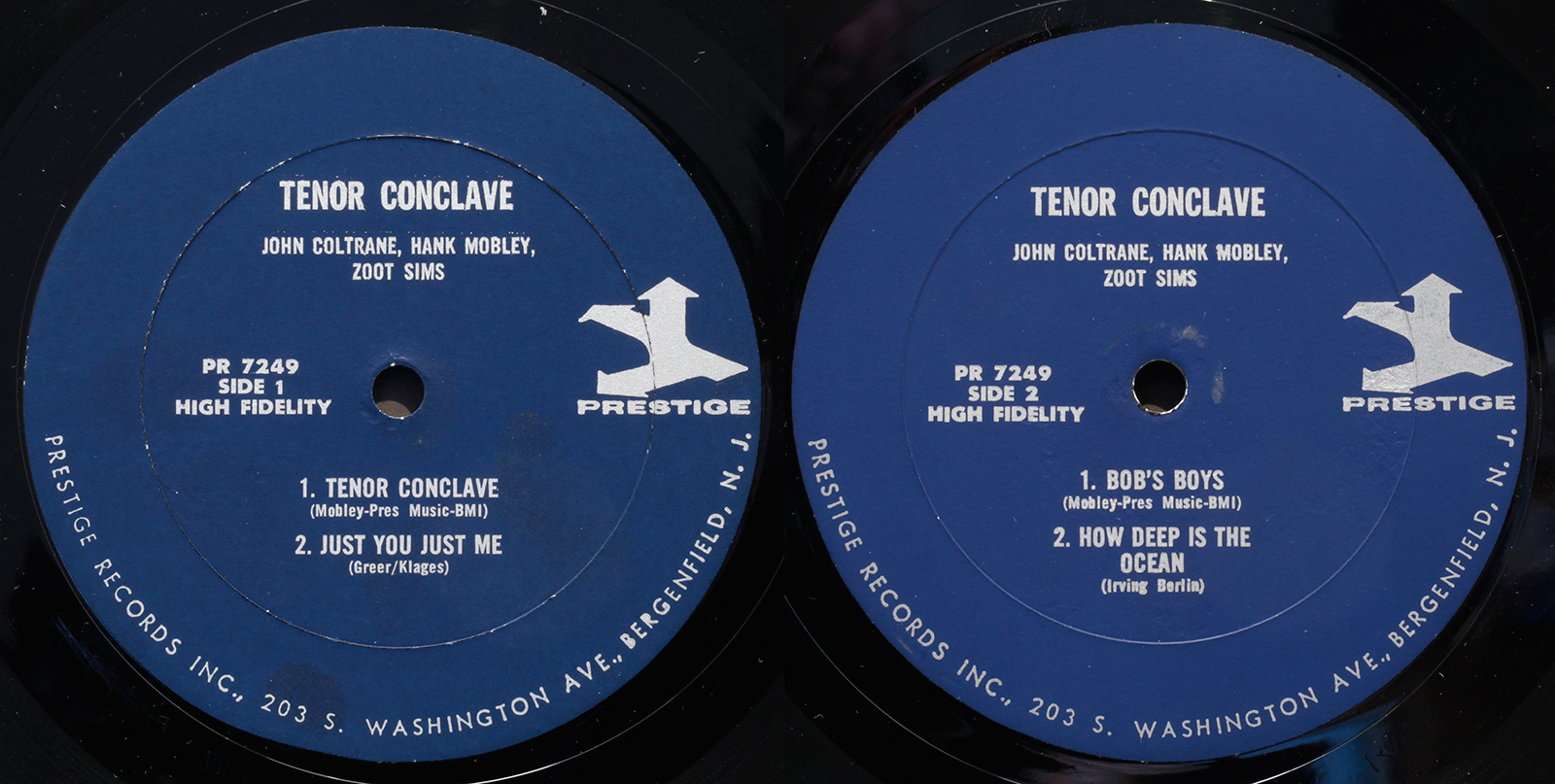

No one is listed as the leader on the session, although it may have sort of been Hank Mobley, who contributed two original compositions (the other two tunes are standards). Eventually, as John Coltrane's star continued to rise, the album was reissued under his name. Interestingly, although that star continued until Trane had risen to the firmament populated by Miles, Bird and Armstrong, it's the leaderless Tenor Conclave cover that adorned the CD reissue.

And no one takes over as leader, or tries to. in her liner notes to the reissue, Ann Giudici* says

As opposed to the popular "cutting session" of years gone by, this date merely offers four different players a chance to display their ideas. No one was out to blow the other off the stand. The atmosphere is one of forceful but relaxed blowing."Maybe this is a characteristic of jazz of the Fifties. Certainly we've heard competitive sessions, like the Coltrane/Sonny Rollins Tenor Madness. But as often as not, the leitmotif is camaraderie. We heard it in the earlier Prestige All-Stars session, with Art Farmer, Donald Byrd and Jackie McLean. Or the Phil Woods session from back in June, with Woods and Gene Quill paired on altos, Donald Byrd and Kenny Dorham on trumpets.

How good an album is this?

Very, very good.

Is it four times as good as an album with one of them?

The answer is yes and no.

No, because if you compare it with albums featuring any one of them -- say, John Coltrane with the Red Garland Trio, one of my all time favorites, and also on Prestige, you wouldn't want to even consider the question of which one is better. It would be like choosing between your children.

But yes, because it's mythic. Like knowing that "Tenor Madness" is the only recorded collaboration between Coltrane and Sonny Rollins. Like the discovery, five decades after the fact, of a live recording of Coltrane and Thelonious Monk at Town Hall.

The myth is important. One of the wonders of art is that it stays with you, and gestates inside your mind and your soul until it becomes a new entity, the offspring of you and the artist(s). And that new enitycomes out into the world and plays with new friends, half-sisters and brothers, the offspring of the artist(s) and your friends, or people you meet in online forums, or people you meet by reading their books and articles and liner notes and poems (like Michael S. Harper's paeans to Dear John, Dear Coltrane). Imagine making love to someone after listening, together, to Stan Getz or Louis Armstrong or Ornette Coleman. You're imagining (or better yet) remembering three very different experiences, aren't you? And each one with a special richness that would not be there without Stan or Louis or Ornette. **

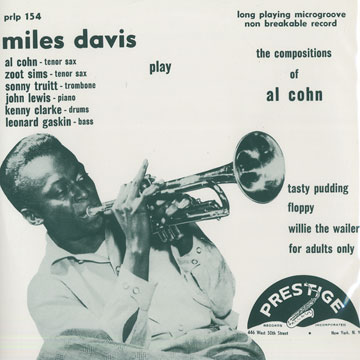

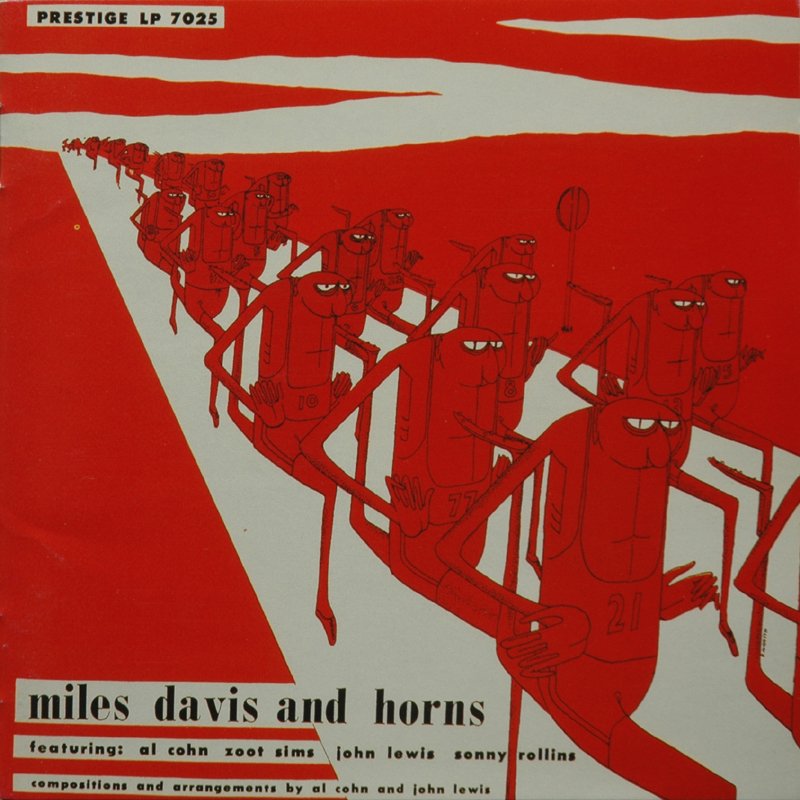

Part of that gestation is the art itself, and part is the history, the personalities, the stories--especially in jazz, which is such a collaborative art, and such an endless melding and blending and separating of personalities and sensibilities, the Miles Davis nonet or J.J. and Kai or James Moody and Tito Puente or the musicians Norman Granz brought together for Jazz at the Philharmonic or Ella Fitzgerald and George Gershwin.

In a review of the album on allmusic.com, Lindsay Planer says that " It takes a couple of passes and somewhat of a trained ear to be able to link the players with their contributions," and this is certainly true to my not very trained ear, but the sense of those different voices and sensibilities coming together is palpable and intoxicating. The London Jazz Collector, in his blog, characterizes the four voices as "Mobley’s tone is pure chocolate, Coltrane is spiced lime, Sims is a good Claret, Cohn is mocha garnacha." Which is beautiful and allusive and mysterious, especially since I had no idea what mocha garnacha is.

Ira Gitler, always helpful, runs down the solos in his liner notes to the original album:

* Always interested in new names that crop up on the periphery of the music and the scene, I looked up Ann Giudici and found not very much. In the early 60s, she was apparently producing plays off-Broadway, and Hackensack station WJRZ, which was having success with old time radio dramas, hired Ann Giudici to produce original dramas and adaptations of short stories with a local repertory company. JRZ had a varied format including jazz (Les Davis was a DJ), but shortly afterwards they switched to an all-country format.

** Here's an imagined look at jazz and lovemaking. This will be included in my forthcoming collaboration between me (poems) and Nancy Ostrovsky (drawings), She Took Off Her Dress.

SHE SAID

She said jazz

is how life should be

flexible rhythm but

you count it off

beyond that

improvisation

melody left behind

now it’s your call

you know where

the roots are you don’t

know where it’s taking you

she herself was

Chet Baker

Gerry Mulligan

touching where you didn’t

know you tingled

or she was

Thelonious Monk

threading her way along

narrow pathways

with broad steps

on either side are

Arizona cactus

long spined blooming

endangered

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 1: 1949-1953 from Amazon

** Here's an imagined look at jazz and lovemaking. This will be included in my forthcoming collaboration between me (poems) and Nancy Ostrovsky (drawings), She Took Off Her Dress.

SHE SAID

She said jazz

is how life should be

flexible rhythm but

you count it off

beyond that

improvisation

melody left behind

now it’s your call

you know where

the roots are you don’t

know where it’s taking you

she herself was

Chet Baker

Gerry Mulligan

touching where you didn’t

know you tingled

or she was

Thelonious Monk

threading her way along

narrow pathways

with broad steps

on either side are

Arizona cactus

long spined blooming

endangered

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 1: 1949-1953 from Amazon

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(96)/discogs-images/R-2873252-1320399681.jpeg.jpg)