Prestige had recorded Joe Holiday and Billy Taylor, separately and together, playing their own fusion of mambo and bebop, but this was their first foray into presenting a strictly Latin ensemble. There are a sprinkling of gringos (including the multitalented Don Elliott) , but this appears to have been a Latin session, aimed at a Latin market. There is one jazz tune in the session, Tirado's version of "Farmer's Market," but even that is given a subtitle, "El Baile del Campesino," or "Peasant Dance." Presumably it would have gone out to Latin markets under the subtitle -- that is, if it had ever gone out at all. "Cha Cheando" and "Shake it Easy" were released on 78 and 45, but the other two were unissued.

Which makes it ironic that the only cut from the session that still seems to exist is one of the unissued ones -- in fact, the very same "Farmer's Market Mambo," which exists on a DJ copy, and can be found on YouTube and on the Office Naps roundup of Latin jazz on Prestige.

There was a brief craze for doing mambo versions of popular standards, including Henry Mancini's jazz theme from Peter Gunn, turned by Jack Costanzo into the "Peter Gunn Mambo," but that all came later, and anyway, although "Peter Gunn" has solid jazz credentials, it was a pop hit as well, so the "Farmer's Market Mambo" may well be unique.

This is the first mambo session on Prestige that does not use a conventional jazz drum kit. All the percussion is on Latin instruments, and the beat is completely Latin. The solos by Don Elliott and Tirado, but especially the Elliott solo, are jazz. There is one other Tirado recording available, "Dorotea" on the primarily R&B Derby label, and it doesn't have the same jazz feel.

Tad Richards' odyssey through the catalog of Prestige Records:an unofficial and idiosyncratic history of jazz in the 50s and 60s. With occasional digressions.

Monday, June 29, 2015

Sunday, June 28, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 125: Gene Ammons

Gene Ammons is back on Prestige for the first time since his flurry of activity in 1950-51, still with the septet form that seemed to appeal to him, but with a new supporting cast -- no Sonny Stitt, and no Bill Massey, the trumpeter who had been the constant in his earlier groups. But he was back to stay: there may have been no other jazz artist who made as many recordings for Prestige as Ammons. He was one of the only musicians who was still putting out new material after Prestige had been sold to Fantasy in 1972 and become mostly a reissue label.

This session appears divided into two distinct groups. "Sock" and "What I Say" (not the Ray Charles song) are, I'm guessing, Ammons originals, and they are Ammons all the way--the rhythm and blues tone and the bebop phrasing. I'm guessing these were aimed at jukeboxes, and at the new emerging jukebox market. There's a scene in Clint Eastwood's Bird in which a strung-out Charlie Parker stumbles backstage at the Apollo and hears an old competitor out on the stage, blowing a wild, theatrical, Big Jay McNeely-type solo, to wild applause. "What's he doing playing rhythm and blues?" Parker wonders, and the other musicians backstage howl with laughter. "Where you been, Bird? That ain't rhythm and blues. That is rock and roll!"

"Sock" was released on 78 b/w a tune from an early 1955 session called "Blues Roller," and then again on 45 b/w a tune from a later 1955 session called "Rock-Roll." It still looks back to the 40s of Illinois Jacquet and the swing-to-bop purveyors of rhythm and blues, rather than ahead to the rock-and-rolling 50s of tenormen like Red Prysock and Sam "the Man" Taylor. "What I Say" is similar. Both tunes have real excitement and some solid blowing. "What I Say" came out on a 78 with a ballad, "Our Love Is Here To Stay," on the flip side, and this too was characteristic of the era, covering one's commercial bets with a honker on one side and a ballad on the other, just as the early Elvis Presley singles on Sun had an R&B tune one side and a country tune on the other, and many of the urban harmony groups would pair up a ballad and a jump tune.

The other two tunes have to have been aimed at very different jukeboxes. "Count Your Blessings" and "Cara Mia," which were released as

two sides of a 78, were both pop tunes of 1954, and neither has exactly

gone on to become a standard of any jazzman's repertoire, although

Sonny Rollins did record "Count Your Blessings." It was written by

Irving Berlin for the Bing Crosby/Danny Kaye movie, White Christmas, the schmaltzy remake of the Crosby/Fred Astaire Holiday Inn. Irving Berlin certainly knew how to write a melody, and this version would go well for an end-of-the-evening slow dance, while still offering some worthwhile Ammons soloing. "Cara Mia" was credited to Tulio Trapani, which was a pseudonym. Actually, the song was written by Mantovani. It was a huge hit in England, and a top ten hit in the US. It's not as good a song as "Count Your Blessings," and I have to wonder if Ammons played it a whole lot in club dates.

The other two tunes have to have been aimed at very different jukeboxes. "Count Your Blessings" and "Cara Mia," which were released as

two sides of a 78, were both pop tunes of 1954, and neither has exactly

gone on to become a standard of any jazzman's repertoire, although

Sonny Rollins did record "Count Your Blessings." It was written by

Irving Berlin for the Bing Crosby/Danny Kaye movie, White Christmas, the schmaltzy remake of the Crosby/Fred Astaire Holiday Inn. Irving Berlin certainly knew how to write a melody, and this version would go well for an end-of-the-evening slow dance, while still offering some worthwhile Ammons soloing. "Cara Mia" was credited to Tulio Trapani, which was a pseudonym. Actually, the song was written by Mantovani. It was a huge hit in England, and a top ten hit in the US. It's not as good a song as "Count Your Blessings," and I have to wonder if Ammons played it a whole lot in club dates.

The first album release of this session did not come until 1965, as Gene Ammons -- Sock! The album's title strongly suggests that it was aimed more at the traditional Ammons audience than the Ammons/Mantovani audience.

This session appears divided into two distinct groups. "Sock" and "What I Say" (not the Ray Charles song) are, I'm guessing, Ammons originals, and they are Ammons all the way--the rhythm and blues tone and the bebop phrasing. I'm guessing these were aimed at jukeboxes, and at the new emerging jukebox market. There's a scene in Clint Eastwood's Bird in which a strung-out Charlie Parker stumbles backstage at the Apollo and hears an old competitor out on the stage, blowing a wild, theatrical, Big Jay McNeely-type solo, to wild applause. "What's he doing playing rhythm and blues?" Parker wonders, and the other musicians backstage howl with laughter. "Where you been, Bird? That ain't rhythm and blues. That is rock and roll!"

"Sock" was released on 78 b/w a tune from an early 1955 session called "Blues Roller," and then again on 45 b/w a tune from a later 1955 session called "Rock-Roll." It still looks back to the 40s of Illinois Jacquet and the swing-to-bop purveyors of rhythm and blues, rather than ahead to the rock-and-rolling 50s of tenormen like Red Prysock and Sam "the Man" Taylor. "What I Say" is similar. Both tunes have real excitement and some solid blowing. "What I Say" came out on a 78 with a ballad, "Our Love Is Here To Stay," on the flip side, and this too was characteristic of the era, covering one's commercial bets with a honker on one side and a ballad on the other, just as the early Elvis Presley singles on Sun had an R&B tune one side and a country tune on the other, and many of the urban harmony groups would pair up a ballad and a jump tune.

The other two tunes have to have been aimed at very different jukeboxes. "Count Your Blessings" and "Cara Mia," which were released as

two sides of a 78, were both pop tunes of 1954, and neither has exactly

gone on to become a standard of any jazzman's repertoire, although

Sonny Rollins did record "Count Your Blessings." It was written by

Irving Berlin for the Bing Crosby/Danny Kaye movie, White Christmas, the schmaltzy remake of the Crosby/Fred Astaire Holiday Inn. Irving Berlin certainly knew how to write a melody, and this version would go well for an end-of-the-evening slow dance, while still offering some worthwhile Ammons soloing. "Cara Mia" was credited to Tulio Trapani, which was a pseudonym. Actually, the song was written by Mantovani. It was a huge hit in England, and a top ten hit in the US. It's not as good a song as "Count Your Blessings," and I have to wonder if Ammons played it a whole lot in club dates.

The other two tunes have to have been aimed at very different jukeboxes. "Count Your Blessings" and "Cara Mia," which were released as

two sides of a 78, were both pop tunes of 1954, and neither has exactly

gone on to become a standard of any jazzman's repertoire, although

Sonny Rollins did record "Count Your Blessings." It was written by

Irving Berlin for the Bing Crosby/Danny Kaye movie, White Christmas, the schmaltzy remake of the Crosby/Fred Astaire Holiday Inn. Irving Berlin certainly knew how to write a melody, and this version would go well for an end-of-the-evening slow dance, while still offering some worthwhile Ammons soloing. "Cara Mia" was credited to Tulio Trapani, which was a pseudonym. Actually, the song was written by Mantovani. It was a huge hit in England, and a top ten hit in the US. It's not as good a song as "Count Your Blessings," and I have to wonder if Ammons played it a whole lot in club dates.The first album release of this session did not come until 1965, as Gene Ammons -- Sock! The album's title strongly suggests that it was aimed more at the traditional Ammons audience than the Ammons/Mantovani audience.

Saturday, June 27, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 124: Art Farmer

I hate that name, but I’m stuck with it. That was made by a trumpet-maker named David Monette, who makes trumpets for a lot of very fine trumpet players, such as Wynton Marsalis, for instance, and the principal players for the Boston Symphony and the Chicago Symphony and the Chicago Symphony, etcetera. I asked him to make me a trumpet, and he made it, it was very fine, and I started really working on the trumpet. Then he got the idea that it didn’t really sound like me, but he wanted to make a flugelhorn for me — so I told him to go ahead and do it. Then he called up one day, and he said, “Well, I made it very carefully and put every part in order, made it by hand [because everything is made by hand], but it sounds like hell, and I really don’t like it. But I have another idea.” So I told him to go ahead and make it. Then a couple of months later, he called and said, “it’s ready.” I went to Chicago, where I was booked, and he brought it on the gig — and right from the start, it sounded like the answer to my prayers...you could go one way or the other on it. You could approximate the warmth of the flugelhorn or you could approximate the projection of the trumpet. If you really wanted to put a note out there, you could do it, and if you wanted to be more intimate, you could do that also. So it seemed like what I was looking for.He would play in a wide variety of settings, from Charles Mingus to Horace Silver to Gerry Mulligan, from the big bands of Quincy Jones, Oliver Nelson and George Russell, to sessions with the French composer Edgar Varèse, because of his reputation as a guy who could play anything.

But he was already that guy when he was still Early Art, in 1954. He had started out in high school in LA with schoolmates Hampton Hawes, Sonny Criss, Ernie Andrews, Big Jay McNeely, and Ed Thigpen.* He had played rhythm and blues with Johnny Otis, Kansas City swing with Jay McShann and blues with Big Joe Turner and Pete Johnson (his first recording session), and the intergenerational, genre-defying jazz of Benny Carter, before his breakthrough 1952 session with Wardell Gray, the one that introduced "Farmer's Market." He had been part of the Lionel Hampton European tour that brought so many young musicians together.

And the same is true of Wynton Kelly. He's probably best known for his work with Miles Davis (including one track on Kind of Blue) during the same time period that Farmer was with the Jazztet. But Kelly had been playing since his early teens, and had actually been part of a Number One rhythm and blues hit in 1948 -- Hal Singer's "Cornbread."

Addison Farmer, Art's twin, also started young out on the West Coast, playing the house band of the R&B label Modern, and recording a bebop session with Teddy Edwards. When he and Art hooked up for this session, he had taken up residence in New York and studied at Juilliard and the Manhattan School of Music, as well as taking private lessons from New York Philharmonic double bassist Fred Zimmerman.

This session features a lot of standards, though if the definition of a standard is one where everyone knows the melody and can sing along at least a couple of choruses, most of these barely qualify. The one solid classic is Frank Loesser's "I've Never Been in Love Before," from Guys and Dolls, to my mind the greatest musical score ever. Farmer and Kelly take it at a brisker tempo than the many ballad singers who've done it, but they still keep it a ballad, and beautiful.

But the others have attracted jazz musicians before and since -- Charlie Parker recorded "I'll Walk

Alone," Chet Baker and Paul Desmond have each done "Alone Together," and "Autumn Nocturne," by film score composer, has become something of a jazz standard.

Alone," Chet Baker and Paul Desmond have each done "Alone Together," and "Autumn Nocturne," by film score composer, has become something of a jazz standard.All of them, and the one original, "Preamp," give much to love, and give plenty of reasons why this is more than "early Art," or early Wynton, for that matter.

"I'll Walk Alone"/"Autumn Nocturne" were released on 78. The session came out on a 10-inch LP in 1955, and then not again ill the reissue days many years later.

* Funny, that's two straight blog entries, two opposite coasts, two guys right around the same time hanging out with a bunch of kids who would go on to become giants of jazz. In the Monk/Rollins entry we saw the young Art Taylor with Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean, Kenny Drew and Andy Kirk Jr.

Wednesday, June 24, 2015

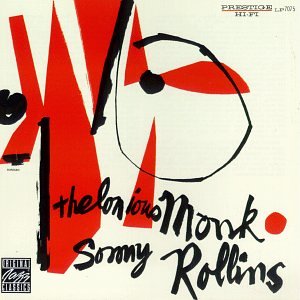

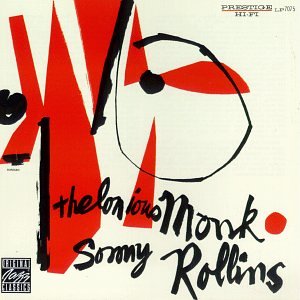

Listening to Prestige Part 123 - Thelonious Monk/Sonny Rollins

This session has Monk and Rollins recording three standards, with bebop veteran Tommy Potter and a young Art Taylor. Taylor would go on to be a mainstay at Prestige, but this was his label debut. He had recorded once for Blue Note, with Bud Powell and George Duvivier, but he had been active on the jazz scene since the late 40s--earlier, if you count his school days in Harlem with Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean, Kenny Drew and Andy Kirk Jr.

But I started listening to these recordings, and I started thinking about ballads, and jazz.

I've written before about the American Century in music, that great artistic flowering that grew out of the blues, and generated such a profusion of genius in such a range of musical styles.

And many people have written, correctly, about exploitation of black music, black culture, and especially black musicians and composers. Ta-Nehisi Coates has written a brilliant article on the case for reparations -- the argument that

The economics of American music have mostly flowed one way, from black creators into white pockets. And yes, I know about the empires built by P. Diddy and Jay-Z and Russell Simmons, and more power to them, but they're still the exception, and historically they're a blip. Joseph Smith, who had some success as Sonny Knight in the 50s, as a rhythm and blues performer, later wrote a scathing and underrated novel about the white-dominated music business of his era, The Day the Music Died.

But that. too, is only part of the story. The greatness of American music is in its impurity, its mongrel nature, its ability to reach out, gather in, and blend. Economically, everything may have flowed one way, but musically, there was cross-pollination. While Elvis was covering the songs of Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup and Roy Brown, and recording the songs of Otis Blackwell, streetcorner groups from Harlem were finding new ways of interpreting standards like "Sunday Kind of Love" and "Over the Rainbow" and "Glory of Love." Earlier, Louis Armstrong had created a timeless classic from Carmen Lombardo's "Sweethearts on Parade." Jazz connoisseurs have chuckled indulgently over Armstrong's fondness for Guy Lombardo's orchestra, but Armstrong heard something in the Lombardo brothers that the rest of us didn't.

Much has been written about the Great American Songbook, and the songs which have become such a part of the soundtrack of our lives, and certainly those songs stand on their own. But the European tradition of composers like Gershwin was immeasurably enriched by their discovery and appreciation of jazz.

Perhaps the first European composer to fully appreciate this was the Czech Antonin Dvorak, who said:

But nothing lasts forever, or at least nothing lasts forever without changing. Shakespeare changes with each new generation, each new production, each new interpretation. And the songs of Gershwin and Kern and Porter and the rest might not have remained such an important part of American culture if they hadn't become part of the repertoire of black singers, who come from a different musical place, a different cultural awareness. Pop singers like Ethel Waters and Lena Horne and Nancy Wilson. Jazz singers like Billie Holiday and Ella and Sarah, Carmen MacRae, DeeDee Bridgewater, Nnenna Freelon.

But I wonder if people have thought much about the impact of modern jazz on the Great American Songbook. The great jazz improvisers added a whole new dimension to these songs, and I believe, gave them new relevance. Even the Tony Martin or Jerry Vale fan, listening to Miles or Sonny or Phil Woods (or Billy Taylor or Marian McPartland or Errol Garner) go off into an improvisation, and wishing they'd come back to playing the melody -- yeah, even the squares knew that when a great modern jazz musician did play the head, he was bringing something new and strange and wonderful to that melody. The modern jazz players, creating a new music from deep in the black experience, incorporated the songs of European-American composers (and European composers like Debussy). They took, and they gave back. And that's American music.

Jerome Kern wrote the melody to "The Way You Look Tonight." When he played it for lyricist Dorothy Fields, she cried. There maybe aren't a lot of melodies these days that can make you cry. But it was the age of melody. Great lyricists like Dorothy Fields added something vital to a song, but the composer was king. His name always came first in the song's credits.

Jerome Kern wrote the melody to "The Way You Look Tonight." When he played it for lyricist Dorothy Fields, she cried. There maybe aren't a lot of melodies these days that can make you cry. But it was the age of melody. Great lyricists like Dorothy Fields added something vital to a song, but the composer was king. His name always came first in the song's credits.

"The Way You Look Tonight" was written for Fred Astaire, and if a song is written for Fred Astaire, it's a good bet that it swings, and that it will be a natural for jazz musicians of any school. It's been recorded by Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, by Miles Davis and Dave Brubeck and Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson and Johnny Griffin and Herbie Hancock. And the song crossed another generational and cultural gap when it was adopted by the streetcorner harmonizers in the style that became known as doowop. Several groups recorded it, including the interracial foursome from Los Angeles, the Jaguars, who transformed it into something different, and something beautiful, in an era when harmony was king.

Interestingly, the beboppers, in mining the Great American Songbook, didn't stop with the Gershwins

and Kerns and the other jazz-influenced composers. They recorded songs by composers who came out of an earlier tradition, who were really from the operetta era, like Sigmund Romberg and Victor Herbert. Vincent Youmans is really of that school, too, and the other two songs from this session are both by Youmans. But Rollins and Monk find gold in them, find the basis for improvisation and innovation and discovery. I can imagine Jerome Kern listening with wonder and admiration to what Monk and Rollins do with his song. It's harder to imagine Youmans having the same reaction.

Monk and Rollins are wonderful collaborators, and they work together by letting good fences make good neighbors. Each gives the other extensive solo space. There's not much in the way of duet voicing, or trading riffs. Tony Martin/Jerry Vale/square though I may be, I think my favorite part of the session is Sonny Rollins's lyrical and imaginative statement of the melody in "The Way You Look Tonight," which is enough to make anyone cry.

This session was first released on a 10-incher which saw Sonny Rollins get top billing. "More Than You Know" was also put onto the Sonny Rollins - Moving Out LP along with the tunes recorded in August with Kenny Dorham and Elmo Hope. "The Way You Look Tonight" and "I Want to Be Happy" were grouped with the tunes from Monk's September trio session on an eponymous album in 1957, which was then rereleased as Work in 1959. This was Monk's swan song on Prestige, as he moved over to Riverside.

But I started listening to these recordings, and I started thinking about ballads, and jazz.

I've written before about the American Century in music, that great artistic flowering that grew out of the blues, and generated such a profusion of genius in such a range of musical styles.

And many people have written, correctly, about exploitation of black music, black culture, and especially black musicians and composers. Ta-Nehisi Coates has written a brilliant article on the case for reparations -- the argument that

America has prospered off the backs of black people, not just in wealth, but “Our policies, our social safety net, the way we think about housing in this country, social security, the GI Bill — these things would not have been possible unless we made certain compromises with white supremacists, to be perfectly honest about that.”Sometimes left out of this argument is yet another black creation that may be America's most profound export, and one of its most financially rewarding -- rock and roll. Which is a white expropriation of a black art form.

The economics of American music have mostly flowed one way, from black creators into white pockets. And yes, I know about the empires built by P. Diddy and Jay-Z and Russell Simmons, and more power to them, but they're still the exception, and historically they're a blip. Joseph Smith, who had some success as Sonny Knight in the 50s, as a rhythm and blues performer, later wrote a scathing and underrated novel about the white-dominated music business of his era, The Day the Music Died.

But that. too, is only part of the story. The greatness of American music is in its impurity, its mongrel nature, its ability to reach out, gather in, and blend. Economically, everything may have flowed one way, but musically, there was cross-pollination. While Elvis was covering the songs of Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup and Roy Brown, and recording the songs of Otis Blackwell, streetcorner groups from Harlem were finding new ways of interpreting standards like "Sunday Kind of Love" and "Over the Rainbow" and "Glory of Love." Earlier, Louis Armstrong had created a timeless classic from Carmen Lombardo's "Sweethearts on Parade." Jazz connoisseurs have chuckled indulgently over Armstrong's fondness for Guy Lombardo's orchestra, but Armstrong heard something in the Lombardo brothers that the rest of us didn't.

Much has been written about the Great American Songbook, and the songs which have become such a part of the soundtrack of our lives, and certainly those songs stand on their own. But the European tradition of composers like Gershwin was immeasurably enriched by their discovery and appreciation of jazz.

Perhaps the first European composer to fully appreciate this was the Czech Antonin Dvorak, who said:

"In the Negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music. They are pathétic, tender, passionate, melancholy, solemn, religious, bold, merry, gay or what you will. It is music that suits itself to any mood or purpose. There is nothing in the whole range of composition that cannot be supplied with themes from this source. The American musician understands these tunes and they move sentiment in him."I'd read Dvorak's famous pronouncement before, but I hadn't seen some of the unsurprising responses to it by conservatorians of the day:

Dr. Dvorak is probably unacquainted with what has already been accomplished in the higher forms of music by composers in America. In my estimation, it is a preposterous idea to say that in future American music will rest upon such an alien foundation as the melodies of a yet largely undeveloped race.

Quaint as those songs may be, it is a poor fountain from which the young American composer could sip his inspirations.And, to be fair, those weren't the only responses.

To the Editor of the Herald: It gives me pleasure to indorse [endorse] the ideas advanced by Antonin Dvorak. I have long felt that Americans have not appreciated the beauty and originality of our native melodies. We possess a mine of folk-song, such as few, if any nation have, and it would be well if our composers should employ those themes in writing their works. In this way we should develop a really American school of music, and find our public would gladly encourage the movement. As it is the treatment of a simple melody which evinces true musicianship, why should not our composers select such airs, instead of going abroad for their ideas?George Gershwin was probably the first, and probably the greatest composer of his age to be profoundly influenced by jazz. Still, at least until Porgy and Bess, his songs were originally written for and sung by white singers, as were the songs of all the popular composers of the day, the ones writing what became the Great American Songbook.

But nothing lasts forever, or at least nothing lasts forever without changing. Shakespeare changes with each new generation, each new production, each new interpretation. And the songs of Gershwin and Kern and Porter and the rest might not have remained such an important part of American culture if they hadn't become part of the repertoire of black singers, who come from a different musical place, a different cultural awareness. Pop singers like Ethel Waters and Lena Horne and Nancy Wilson. Jazz singers like Billie Holiday and Ella and Sarah, Carmen MacRae, DeeDee Bridgewater, Nnenna Freelon.

But I wonder if people have thought much about the impact of modern jazz on the Great American Songbook. The great jazz improvisers added a whole new dimension to these songs, and I believe, gave them new relevance. Even the Tony Martin or Jerry Vale fan, listening to Miles or Sonny or Phil Woods (or Billy Taylor or Marian McPartland or Errol Garner) go off into an improvisation, and wishing they'd come back to playing the melody -- yeah, even the squares knew that when a great modern jazz musician did play the head, he was bringing something new and strange and wonderful to that melody. The modern jazz players, creating a new music from deep in the black experience, incorporated the songs of European-American composers (and European composers like Debussy). They took, and they gave back. And that's American music.

Jerome Kern wrote the melody to "The Way You Look Tonight." When he played it for lyricist Dorothy Fields, she cried. There maybe aren't a lot of melodies these days that can make you cry. But it was the age of melody. Great lyricists like Dorothy Fields added something vital to a song, but the composer was king. His name always came first in the song's credits.

Jerome Kern wrote the melody to "The Way You Look Tonight." When he played it for lyricist Dorothy Fields, she cried. There maybe aren't a lot of melodies these days that can make you cry. But it was the age of melody. Great lyricists like Dorothy Fields added something vital to a song, but the composer was king. His name always came first in the song's credits."The Way You Look Tonight" was written for Fred Astaire, and if a song is written for Fred Astaire, it's a good bet that it swings, and that it will be a natural for jazz musicians of any school. It's been recorded by Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, by Miles Davis and Dave Brubeck and Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson and Johnny Griffin and Herbie Hancock. And the song crossed another generational and cultural gap when it was adopted by the streetcorner harmonizers in the style that became known as doowop. Several groups recorded it, including the interracial foursome from Los Angeles, the Jaguars, who transformed it into something different, and something beautiful, in an era when harmony was king.

Interestingly, the beboppers, in mining the Great American Songbook, didn't stop with the Gershwins

and Kerns and the other jazz-influenced composers. They recorded songs by composers who came out of an earlier tradition, who were really from the operetta era, like Sigmund Romberg and Victor Herbert. Vincent Youmans is really of that school, too, and the other two songs from this session are both by Youmans. But Rollins and Monk find gold in them, find the basis for improvisation and innovation and discovery. I can imagine Jerome Kern listening with wonder and admiration to what Monk and Rollins do with his song. It's harder to imagine Youmans having the same reaction.

Monk and Rollins are wonderful collaborators, and they work together by letting good fences make good neighbors. Each gives the other extensive solo space. There's not much in the way of duet voicing, or trading riffs. Tony Martin/Jerry Vale/square though I may be, I think my favorite part of the session is Sonny Rollins's lyrical and imaginative statement of the melody in "The Way You Look Tonight," which is enough to make anyone cry.

This session was first released on a 10-incher which saw Sonny Rollins get top billing. "More Than You Know" was also put onto the Sonny Rollins - Moving Out LP along with the tunes recorded in August with Kenny Dorham and Elmo Hope. "The Way You Look Tonight" and "I Want to Be Happy" were grouped with the tunes from Monk's September trio session on an eponymous album in 1957, which was then rereleased as Work in 1959. This was Monk's swan song on Prestige, as he moved over to Riverside.

Tuesday, June 23, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 122 - Phil Woods

When I started this project, my goal was to listen to at least one cut from every Prestige album in chronological order. That went out the window pretty quickly when I realized that to do a proper chronology, I'd have to do it session by session, not album by album. And it really went out the window when I discovered that one cut was nowhere near enough. It might take a substantial chunk of time, but what better to do with my time than listen to jazz on Prestige? I was going to listen to every recording ever made for Bob Weinstock's label.

When possible. Some things I just haven't been able to find, and that would include most of this session. "Open Door" has been put up on YouTube, and that's it.

Still, every limitation has its compensations. In this case, instead of listening to four songs in rotation, I've focused on just the one, appreciating that if two guys were ever made to play together, it's Phil Woods and Jon Eardley. Of course, Phil Woods played with so many different musicians, and sounded great with all of them.

This was his first session as a leader, and maybe only his second recording session. I haven't found anything else besides the Jimmy Raney session just two months earlier. He was only 23 when he made these recordings.

George Syran seems only to have recorded on a handful of sessions with either Woods or Eardley, but his obituary (2005) offers this:

That's a pro's pro who can fit in anywhere, but he definitely knew how to play jazz. He has a strong solo here.

Nick Stabulas is a powerful presence throughout.

These were released on New Jazz, and the New Jazz releases seem in general to be less reissued and harder to find. "Pot Pie" and "Mad About the Girl" were also on a Prestige EP.

When possible. Some things I just haven't been able to find, and that would include most of this session. "Open Door" has been put up on YouTube, and that's it.

Still, every limitation has its compensations. In this case, instead of listening to four songs in rotation, I've focused on just the one, appreciating that if two guys were ever made to play together, it's Phil Woods and Jon Eardley. Of course, Phil Woods played with so many different musicians, and sounded great with all of them.

This was his first session as a leader, and maybe only his second recording session. I haven't found anything else besides the Jimmy Raney session just two months earlier. He was only 23 when he made these recordings.

George Syran seems only to have recorded on a handful of sessions with either Woods or Eardley, but his obituary (2005) offers this:

Mr. Syrianoudis played with Billy May, Hal McIntyre, Jimmy Dorsey, Richard Maltby, Cannonball Adderley, Al Cohn, Phil Woods, Lester Lanin, Dick Meldonian, Hal Prince and many others.

He was the personal accompanist for Buddy Greco, Don Rondo and Morgana King.

That's a pro's pro who can fit in anywhere, but he definitely knew how to play jazz. He has a strong solo here.

Nick Stabulas is a powerful presence throughout.

These were released on New Jazz, and the New Jazz releases seem in general to be less reissued and harder to find. "Pot Pie" and "Mad About the Girl" were also on a Prestige EP.

Listening to Prestige Part 122 - James Moody

James Moody is back in the studio with essentially the same band he used in his January and February sessions for Prestige, the first named having particular significance as the first session engineered by Rudy Van Gelder in his parents' newly remodeled living room in Hackensack. The only new face in this session is drummer Clarence Johnston.

This is a band of musicians, who, like Moody, were Dizzy Gillespie big band alumni. They didn't all go on to record as leaders, or even appear on many small group recordings, but as Rudyard Kipling said, referring to the schoolmasters who are often the butt of pranks in his semi-autobiographical Stalky and Co.,

When trumpeter Dave Burns passed away in 2003, other trumpeters whose lives he had touched remembered him on a website.

"Blues in the Closet" is particularly interesting. It opens with a lengthy, bluesy, boppy duet between Johnston and bassist John Latham. Maybe they were the only ones who could fit in the closet. Then the closet door opens to let in a blast from the ensemble, then back to the duet, then another ensemble fanfare, and Moody doesn't start soloing until past the two minute mark of a four minute song. The second half is Moody and the ensemble, taking off from the groove Latham and Johnston have laid down for them.

The jazzdisco website lists the final cut as "Moody's Mood for Love," but Moody was moody, and had lots of moods, and this is Moody's Mood for Blues, and yes, this cat, and this group, can play the blues. Oh, my, yes. This one also begins with a great walking bass line.

Quincy Jones did the arrangement for the septet, and composed this Moody's Mood.

"Moody's Mood for Blues" was issued on both sides of a 78, and so was "It Might As Well Be Spring." "Blues in the Closet" and "Moody's Mood" were part of an EP entitled James Moody/Eddie Jefferson: James Moody and the Blues. The whole session was on a 10-inch LP, and it was part of a 7000-series LP called Moody, released in 1956 -- and rereleased in 1959 as a 7100-series LP called Workshop. "It Might as Well Be Spring" was included on a 7000-series LP called James Moody's Moods, rereleased as 7100-series Moody's Workshop.

This is a band of musicians, who, like Moody, were Dizzy Gillespie big band alumni. They didn't all go on to record as leaders, or even appear on many small group recordings, but as Rudyard Kipling said, referring to the schoolmasters who are often the butt of pranks in his semi-autobiographical Stalky and Co.,

"Let us now praise famous men"--These guys played in big bands, and in small clubs, and they taught, and their legacy runs deep, and deserves to be remembered.

Men of little showing--

For their work continueth,

And their work continueth,

Broad and deep continues,

Greater then their knowing!

When trumpeter Dave Burns passed away in 2003, other trumpeters whose lives he had touched remembered him on a website.

I studied jazz improv with Dave for a couple of years. He was a real gentleman and a great, if underrated, player. I used to listen to him years ago at Sonny's Place out on Long Island. Classic bop style player. I'm glad to have known him.Clarence Johnston is still with us, as of this writing, as far as I can tell.This is from a 2011 interview:

I'm a drummer who had the honor of working with Dave in LI clubs in the late 80's early 90's. I was a youngster and he treated me with the respect you would give to other old timers. Peck Morrison often was the bass player and so the breaks were as much fun as the sets. I only wish I could remember all the stories they told. Rest in peace Dave, you gave me some of the greatest experience and memories of my life. I brought my Dad Ted Brown (tenor) to sit in one night and Dave hired him as a regular too. Now I will go look for the recordings we sometimes made.

I was Dave's 2nd student, back in 1970 when he was living in Malverne with his wife Judy. His first Student was Randy Andersen. To say that Dave was a phenomenal player is an understatement. I studied with him on and off for 20 years,and I have never heard incredible playing like his in my life. He was also the same way on the piano and taught you from the piano. He was also the kindest , warmest man you'd ever want to meet. His students always came first. I miss him greatly.

This just breaks my heart- I was a student of Dave's in the '90s and he was one of the finest people/ teachers/ trumpeters I have ever been around. So many good memories of him at the fender rhodes teaching me tunes and phrases. He wasn't playing at all by the time I took lessons from him but one day I finally convinced him to play for me....YIKES! WOW! I still have the recording- it is 16 bars of bebop heaven.

At the age of 86, Clarence Johnston is too busy living in the present to talk much aboutThis session begins with a lovely version of a particularly lovely ballad, "It Might as Well Be Spring." Two takes were preserved. I've only been able to listen to the first, which is Moody at his romantic best.

his past. As a world-renowned jazz drummer he has played over 50 years, traveling and performing with jazz artists Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Dinah Washington among many others. As an Army and Air Force veteran of WWII and growing up in an era where jazz was burgeoning, Mr. Johnston has some colorful stories to share. But because he remains an active professional musician, teacher, storyteller and intergenerational drum circle facilitator, our conversation focused instead on his current enterprises.

Laura Swett: Given all of your current projects, does your age affect you?

Clarence Johnston: I’ll be a bit frank with you. Age is not in my mind at all. I’m a professional musician. All I think of is the next day. I don’t think of age. All I do is work to keep up with what’s going on! I like going from one thing to the next. I still teach, and I still play. And some weeks are better than others.

LS: What do the drums mean to you?

CJ: What I get out of it is a world of happiness. How many people can go through life and do exactly what they feel like doing? You [do] have to discipline yourself for that. Jazz is the hardest music in the world to play; it takes a lot of time and patience. It takes years before you learn it. It’s a particular art, a particular sound and feeling. It took me about 10 or 11 years before I even got that sound right. I was playing but I knew the sound I wanted, and it took time. If you want the instrument to sound the way you want it to, you have to practice. [When you do] it makes you feel good and is a real accomplishment. When you don’t practice you can still play, but you get real slow.

...

LS: How long do you practice?

CJ: I have a studio where I practice. I go four hours a day. Sometimes I work a particular piece and need more time and feel I should be doing this for 8 hours.`

"Blues in the Closet" is particularly interesting. It opens with a lengthy, bluesy, boppy duet between Johnston and bassist John Latham. Maybe they were the only ones who could fit in the closet. Then the closet door opens to let in a blast from the ensemble, then back to the duet, then another ensemble fanfare, and Moody doesn't start soloing until past the two minute mark of a four minute song. The second half is Moody and the ensemble, taking off from the groove Latham and Johnston have laid down for them.

The jazzdisco website lists the final cut as "Moody's Mood for Love," but Moody was moody, and had lots of moods, and this is Moody's Mood for Blues, and yes, this cat, and this group, can play the blues. Oh, my, yes. This one also begins with a great walking bass line.

Quincy Jones did the arrangement for the septet, and composed this Moody's Mood.

"Moody's Mood for Blues" was issued on both sides of a 78, and so was "It Might As Well Be Spring." "Blues in the Closet" and "Moody's Mood" were part of an EP entitled James Moody/Eddie Jefferson: James Moody and the Blues. The whole session was on a 10-inch LP, and it was part of a 7000-series LP called Moody, released in 1956 -- and rereleased in 1959 as a 7100-series LP called Workshop. "It Might as Well Be Spring" was included on a 7000-series LP called James Moody's Moods, rereleased as 7100-series Moody's Workshop.

Sunday, June 21, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 121 - Thelonious Monk

On a technical note, we just got a new car, with Bluetooth connectability to the speaker system, and I finally figured out how to play Spotify through it, so I'm back to my old pattern of driving and listening to a Prestige session. This gives me some serious listening time, as one short drive generally lets me listen to a whole session through twice, and a series of short drives over a couple of days (I live in the country and have a young teenage grandson, so this is the way most of my days go) gives me a real opportunity to spend the kind of time I like with a session.

Especially fortunate that this all got worked out in time for this session, because if you're setting aside some time to spend with these four songs, you're going to need to allow for the circumstance that at first, all you're going to want to do is listen to "Blue Monk." It's that magical.

So many of Monk's greatest compositions were introduced in his recordings of this era for Prestige and Blue Note. Don't forget what it was that inspired Bob Weinstock to start his own record label. He was a 19-year-old kid in his first business venture, running a record store next to the Metropole in Times Square. The Metropole was a home to trad jazz, and that was what Weinstock sold -- on 78, of course. Until...

Anyway, I did finally start listening to the whole set, all the way through -- three Monk originals, with Percy Heath and Art Blakey, and one standard, on which Monk plays solo. "Nutty" and "Work" both have little melodic hints of what would coalesce in "Blue Monk."

Thoughts: on all of the trio tunes, there are extended bass and drum solos, which has not exactly been a hallmark of earlier Prestige sessions. Perhaps we can take this as a tribute to Rudy Van Gelder's increasing confidence in his engineering skills.

And this is all great stuff. A drum solo with a Thelonious Monk trio, on Thelonious Monk tunes, is not exactly going to be a Buddy Rich drum solo, no disrespect to Buddy. Blakey integrates his own propulsive rhythmic mastery with Monk's unique approach to rhythm -- no mean feat, in a drum solo.

When I was young and pretentious, and I went out to jazz clubs, I used to always quietly disapprove of people who applauded at the end of a solo. I wanted to hear the transition, as one soloist handed the ball off to another. I've since learned that you can never have too much applause, that the soloist deserves it, that it's part of the spontaneity of live music. And you can listen to those transitions on the record.

Which I do. I've always been fascinated, in art, in music, in writing, by what happens when something is in the process of stopping being one thing and starting to be another.

And there are some great moments here. In "Nutty," when Blakey's solo seems to rise in pitch at the end, and Monk picks it up at the apex. In "Work," the handoff from Blakey to Heath to Monk.

And all the way through, there are great moments between Monk and Percy Heath. Heath's solos, his dialogs with Monk, their duets, with both instruments threading lines around each other. Outside of the melody of "Blue Monk," these may be my favorite parts of the session.

Finally, there's Monk's short, song-length, unaccompanied take on "Just a Gigolo."

Artists strike out for the deep end in all sorts of ways. If you had been invited out to Rudy Van Gelder's studio in Hackensack to record four songs, and you'd been given Percy Heath and Art Blakey to accompany you, would you do the first three, and then say "Take the rest of the afternoon off, fellas, I'm doing this one on my own"?

Of course, it might not have happened that way. Maybe the session ran long, and Percy and Art had a gig in the city. Or maybe they showed up late, and Monk decided to start without them. But those seem less likely. Monk knew what he was doing when he recorded solo, and he was generally right.

"Blue Monk" was released on a 45 with "Bye-Ya" on the flip. All four cuts were on a 10-inch, Thelonious Monk Trio. "Blue Monk" and "Just a Gigolo" were put on a 12-inch of the same title with the 1952 trio sessions, and the same grouping was rereleased as Monk's Moods. "Work" and "Nutty" joined "Friday the Thirteenth" from Monk's November 1953 session with Sonny Rollins, and a couple of tunes from a later session with Rollins, as Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins, and this album was also rereleased under a different title, Work. The two earlier releases were from the 7000 series in 1957, the later rereleases from the 7100 series in 1959. And of course, there are a number of later reissues.

Especially fortunate that this all got worked out in time for this session, because if you're setting aside some time to spend with these four songs, you're going to need to allow for the circumstance that at first, all you're going to want to do is listen to "Blue Monk." It's that magical.

So many of Monk's greatest compositions were introduced in his recordings of this era for Prestige and Blue Note. Don't forget what it was that inspired Bob Weinstock to start his own record label. He was a 19-year-old kid in his first business venture, running a record store next to the Metropole in Times Square. The Metropole was a home to trad jazz, and that was what Weinstock sold -- on 78, of course. Until...

One day Alfred Lion, who ran Blue Note Records, came in and said, “I have something new: Thelonious Monk." I said, “What the hell's that?" Alfred said, “It's bebop." I listened to it and the more I listened, I realized it had a charm to it. It was interesting. I was strictly into swing at the time. Beboppers were calling people like us moldy figs. The next thing I knew, I became obsessed with bebop. I was attracted like a magnet...I got curious as to some of the recording debuts of classic Monk tunes, so here are a few:

Blue Note 1947

Blue Note 1948

- Ruby, My Dear

- Well, You Needn't

- Round Midnight

- In Walked Bud

Blue Note 1951

- Misterioso

- Epistrophy

Prestige 1951

- Straight No Chaser

Prestige 1952

- Little Rootie Tootie

- Bye-Ya

- Monk's Dream

Prestige 1953

- Trinkle Tinkle

- Bemsha Swing

Prestige 1954Does that say something about (a) how important Monk was, and (b) how important these two jazz labels were?

- We See

- Blue Monk

Anyway, I did finally start listening to the whole set, all the way through -- three Monk originals, with Percy Heath and Art Blakey, and one standard, on which Monk plays solo. "Nutty" and "Work" both have little melodic hints of what would coalesce in "Blue Monk."

Thoughts: on all of the trio tunes, there are extended bass and drum solos, which has not exactly been a hallmark of earlier Prestige sessions. Perhaps we can take this as a tribute to Rudy Van Gelder's increasing confidence in his engineering skills.

And this is all great stuff. A drum solo with a Thelonious Monk trio, on Thelonious Monk tunes, is not exactly going to be a Buddy Rich drum solo, no disrespect to Buddy. Blakey integrates his own propulsive rhythmic mastery with Monk's unique approach to rhythm -- no mean feat, in a drum solo.

When I was young and pretentious, and I went out to jazz clubs, I used to always quietly disapprove of people who applauded at the end of a solo. I wanted to hear the transition, as one soloist handed the ball off to another. I've since learned that you can never have too much applause, that the soloist deserves it, that it's part of the spontaneity of live music. And you can listen to those transitions on the record.

Which I do. I've always been fascinated, in art, in music, in writing, by what happens when something is in the process of stopping being one thing and starting to be another.

And there are some great moments here. In "Nutty," when Blakey's solo seems to rise in pitch at the end, and Monk picks it up at the apex. In "Work," the handoff from Blakey to Heath to Monk.

And all the way through, there are great moments between Monk and Percy Heath. Heath's solos, his dialogs with Monk, their duets, with both instruments threading lines around each other. Outside of the melody of "Blue Monk," these may be my favorite parts of the session.

Finally, there's Monk's short, song-length, unaccompanied take on "Just a Gigolo."

Artists strike out for the deep end in all sorts of ways. If you had been invited out to Rudy Van Gelder's studio in Hackensack to record four songs, and you'd been given Percy Heath and Art Blakey to accompany you, would you do the first three, and then say "Take the rest of the afternoon off, fellas, I'm doing this one on my own"?

Of course, it might not have happened that way. Maybe the session ran long, and Percy and Art had a gig in the city. Or maybe they showed up late, and Monk decided to start without them. But those seem less likely. Monk knew what he was doing when he recorded solo, and he was generally right.

"Blue Monk" was released on a 45 with "Bye-Ya" on the flip. All four cuts were on a 10-inch, Thelonious Monk Trio. "Blue Monk" and "Just a Gigolo" were put on a 12-inch of the same title with the 1952 trio sessions, and the same grouping was rereleased as Monk's Moods. "Work" and "Nutty" joined "Friday the Thirteenth" from Monk's November 1953 session with Sonny Rollins, and a couple of tunes from a later session with Rollins, as Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins, and this album was also rereleased under a different title, Work. The two earlier releases were from the 7000 series in 1957, the later rereleases from the 7100 series in 1959. And of course, there are a number of later reissues.

Thursday, June 18, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 120: Billy Taylor/Candido

Billy Taylor wrote the liner notes for this album, and he made its purpose clear:

Taylor gives Candido a lot of solo space here, and the conguero makes full use of it. He's a powerful presence throughout, soloing and trading with Taylor. And I could say accompanying, but that's not really it. He makes Taylor's solos into duets, and this is in no small part due to Rudy Van Gelder's engineering, keeping the levels of both instruments perfectly complementary.

The tracks are Taylor originals, plus a version of Cole Porter's "Love For Sale" which is breathtaking. Over nearly 8 minutes, Porter's melody becomes Latinized, boppified, turned into a vehicle for some adventurous Taylor improvisation and hot percussion by Candido.

Candido, who is still with us, was named an NEA Jazz Master in 2008, and his brief bio on the NEA's website describes some of his innovative drumming techniques:

I found a fascinating article on Candido at the Drum! website, taken from an article by Bobby

Sanabria (Originally Published in the Autumn 2007 issue of TRAPS) which includes the mention of a group the young Candido played with in Havana, led by Chano Pozo on congas, and including Candido on tres (a Cuban three-stringed instrument designed like either a mandolin or a guitar) and Mongo Santamaria on bongos. He also describes how he came to develop his three-drum technique:

The purpose of this album is to present a great new jazz artist. His name is Candido, and we think that he is the most exciting jazz conga and bongo player in the business.Dizzy Gillespie, of course, is one of the most important figures involved in the integration of Latin rhythms into jazz, starting with bringing Chano Pozo into his band. Even before that, Machito had one of the great jazz trumpeters, Mario Bauza, who never gets the credit he deserves--well, Latin jazz has never really gotten the acclaim it deserves. Candido played with both Machito and Gillespie before joining Billy Taylor for these sessions. Taylor, who would become one of the great educators in the jazz field, seems to have already had that mind set, as he sets out to prove that Latin jazz is real jazz, and Candido Camero is a real jazz musician.

There are, of course, many Latin American drummers who play well with jazz groups, but I have not heard anyone who even approaches the wonderful balance between the jazz and Cuban rhythmic elements that Candido so vividly demonstrates, and his technical facility is, to say the least, astounding.

Taylor gives Candido a lot of solo space here, and the conguero makes full use of it. He's a powerful presence throughout, soloing and trading with Taylor. And I could say accompanying, but that's not really it. He makes Taylor's solos into duets, and this is in no small part due to Rudy Van Gelder's engineering, keeping the levels of both instruments perfectly complementary.

The tracks are Taylor originals, plus a version of Cole Porter's "Love For Sale" which is breathtaking. Over nearly 8 minutes, Porter's melody becomes Latinized, boppified, turned into a vehicle for some adventurous Taylor improvisation and hot percussion by Candido.

Candido, who is still with us, was named an NEA Jazz Master in 2008, and his brief bio on the NEA's website describes some of his innovative drumming techniques:

...playing three congas (at a time when other congueros were playing only one) in addition to a cowbell and guiro (a fluted gourd played with strokes from a stick). He created another unique playing style by tuning his congas to specific pitches so that he could play melodies like a pianist.

I found a fascinating article on Candido at the Drum! website, taken from an article by Bobby

Sanabria (Originally Published in the Autumn 2007 issue of TRAPS) which includes the mention of a group the young Candido played with in Havana, led by Chano Pozo on congas, and including Candido on tres (a Cuban three-stringed instrument designed like either a mandolin or a guitar) and Mongo Santamaria on bongos. He also describes how he came to develop his three-drum technique:

I had seen the New York Philharmonic perform and paid attention to the timpanist. I thought to myself, ’I can do the same thing with the congas.’ I began to tune the drums to specific pitches, mostly a dominant chord, so I could play melodies in my tumbaos and solos.

"A Live One" and "Mambo Inn" were released on an EP, and, with "Love For Sale," as part of a 10-inch LP. Both of these were just credited to Billy Taylor. The 12-inch LP, with the liner notes I quoted above, had the whole session, and was titled The Billy Taylor Trio with Candido.

Friday, June 12, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 119: Joe Holiday/Billy Taylor

Joe Holiday is one of my new favorite musicians--a guy I had never heard of when I started this project, but who I've grown to love over the four previous sessions he recorded for Prestige, establishing himself as the king of mambo jazz.

That being said, listening to this session on the heels of the Sonny Rollins/Kenny Dorham/Elmo Hope session, Holiday is not in their league as an improviser. Where they were Movin' Out, Holiday is more like Stayin' Home. But I tell you, there's nothing wrong with stayin' home if you can roll back the rug, have a couple of rum and cokes, take a cute girl in your arms and do the mambo all night.

If Holiday's improvisations don't break any new ground, he can surely play the bejeezus out of a

melody, he can swing, he can bring Latin to bebop and vice versa.

Billy Taylor's improvisations are a lot more adventurous, but he and Holiday make a good fit. There are all sorts of different ways of being on the same page musically.

But if I were going to give an MVP for this session, I think it would be Charlie Smith. On the earlier Holiday/Taylor collaboration, they had the benefit of Machito's rhythm section. Here Smith handles it all, on traps and congas, and he keeps it going.

The cuts from this session were released as singles. The mambo was still a hot dance craze in 1954. Apparently, they only came out on 78. Perhaps the market for Latin music was still mostly 78 RPM. In the introductory chapter to Oscar Hijuelos' magnificent novel The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, as Cesar Castillo is dying, he stumbles and knocks over a credenza in his apartment, and dozens of 78s fall to the floor and shatter. "I Love You Much" had what seems to be a variously titled song on its flip side. The session list has it as "Chasin' the Bongo," but every 78 RPM catalog I've found lists it as "Chasin' the Boogie." Also, every catalog has an unknown flip side to "It Might As Well Be Spring," but the song was over five minutes long, so it has to have been Part 1 and Part 2. It looks as though no one in recent memory has actually seen a copy of either of these discs. Maybe they were part of Cesar Castillo's record collection.

They were included on the Holiday/Taylor Mambo Jazz 10-inch, then had to wait for years-later reissues.

That being said, listening to this session on the heels of the Sonny Rollins/Kenny Dorham/Elmo Hope session, Holiday is not in their league as an improviser. Where they were Movin' Out, Holiday is more like Stayin' Home. But I tell you, there's nothing wrong with stayin' home if you can roll back the rug, have a couple of rum and cokes, take a cute girl in your arms and do the mambo all night.

If Holiday's improvisations don't break any new ground, he can surely play the bejeezus out of a

melody, he can swing, he can bring Latin to bebop and vice versa.

Billy Taylor's improvisations are a lot more adventurous, but he and Holiday make a good fit. There are all sorts of different ways of being on the same page musically.

But if I were going to give an MVP for this session, I think it would be Charlie Smith. On the earlier Holiday/Taylor collaboration, they had the benefit of Machito's rhythm section. Here Smith handles it all, on traps and congas, and he keeps it going.

The cuts from this session were released as singles. The mambo was still a hot dance craze in 1954. Apparently, they only came out on 78. Perhaps the market for Latin music was still mostly 78 RPM. In the introductory chapter to Oscar Hijuelos' magnificent novel The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, as Cesar Castillo is dying, he stumbles and knocks over a credenza in his apartment, and dozens of 78s fall to the floor and shatter. "I Love You Much" had what seems to be a variously titled song on its flip side. The session list has it as "Chasin' the Bongo," but every 78 RPM catalog I've found lists it as "Chasin' the Boogie." Also, every catalog has an unknown flip side to "It Might As Well Be Spring," but the song was over five minutes long, so it has to have been Part 1 and Part 2. It looks as though no one in recent memory has actually seen a copy of either of these discs. Maybe they were part of Cesar Castillo's record collection.

They were included on the Holiday/Taylor Mambo Jazz 10-inch, then had to wait for years-later reissues.

Wednesday, June 10, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 118: Sonny Rollins

When it comes to ballads as a vehicle for modern jazz, it's hard to beat the standards from the Great American Songbook, and maybe not advisable to try. That's why Sonny Rollins's original composition, "Silk 'n' Satin," on this session, is so stirring. It has the passion and the melodic beauty to stand comparison to Kern or Porter or Gershwin, and given that it's the work of one of our great improvisers, it leaves room for some beautiful improvisation by Rollins, Kenny Dorham, and Elmo Hope.

All of the cuts from this session are Rollins originals, and they cover a lot of territory. "Movin' Out" and "Swinging for Bumsy" are blistering bebop excursions, then the beautiful ballad, and finally the midtempo "Solid."

Dorham and Hope are right with Rollins all the way through, and that takes some doing, because all of the solos are seriously inventive throughout. "Movin' Out" is a succession of rapid-tempo solos, starting with Sonny, and these guys aren't just answering each other, they're answering themselves, playing off their own ideas and finding new directions within each solo. Elmo Hope is the perfect piano player to keep pace and create his own complex improvisations.

In "Swinging for Bumsy," they keep the fire going, ratcheting up the tempo another notch, and this time using short unison bursts to transition from one solo to the next. Art Blakey, due to an equipment malfunction, was playing without his

high-hat cymbals that day, which for a bebop drummer is like a spitball

pitcher being cut off from his slippery elm, but it doesn't slow him down, and he contributes a powerful solo on "Swinging for Bumsy."

In "Swinging for Bumsy," they keep the fire going, ratcheting up the tempo another notch, and this time using short unison bursts to transition from one solo to the next. Art Blakey, due to an equipment malfunction, was playing without his

high-hat cymbals that day, which for a bebop drummer is like a spitball

pitcher being cut off from his slippery elm, but it doesn't slow him down, and he contributes a powerful solo on "Swinging for Bumsy."

Hope is deep and expressive on his ballad solo, and it's one of the emotional highlights of the session.

Rollins and Dorham only play one extended unison part, on the "Solid" head, but they're never far apart. They would come together again two years later as part of the revamped Max Roach Quintet, after the death of Clifford Brown.

Dorham and Hope both died young. Hope, one of the most adventurous and experimental players and composers of the bebop era, survived (particularly worthy of mention with today's headlines being what they are) being shot by a cop as a teenager. Throughout much of his life he battled heroin addiction, and it finally beat him. Dorham died of a kidney disease.

I had thought of both Dorham and Hope as sort of second generation beboppers, coming along in the 50s and 60s, but in fact they were both there from the beginning. Dorham joined Mercer Ellington's band in 1945, at age 21, then followed Dizzy Gillespie as the lead trumpeter in Billy Eckstine's famous band, and from there moved on to Gillespie's band. By the time he made these recordings with Sonny Rollins, he had played with Sonny Stitt, Fats Navarro, Lionel Hampton, Mary Lou Williams and J. J.

I had thought of both Dorham and Hope as sort of second generation beboppers, coming along in the 50s and 60s, but in fact they were both there from the beginning. Dorham joined Mercer Ellington's band in 1945, at age 21, then followed Dizzy Gillespie as the lead trumpeter in Billy Eckstine's famous band, and from there moved on to Gillespie's band. By the time he made these recordings with Sonny Rollins, he had played with Sonny Stitt, Fats Navarro, Lionel Hampton, Mary Lou Williams and J. J.

Johnson, and had had an extended stint with Charlie Parker.

J. R. Monterose, who played with Dorham on his classic 'Round about Midnight at the Cafe Bohemia album, told me that Dorham was the best leader he had ever played with.

These were released on a 10-inch LP titled Sonny Rollins Quintet featuring Kenny Dorham, and on a 12-inch titled Moving Out, which added the "g" to the first word, and added an extended jam featuring Thelonious Monk.

All of the cuts from this session are Rollins originals, and they cover a lot of territory. "Movin' Out" and "Swinging for Bumsy" are blistering bebop excursions, then the beautiful ballad, and finally the midtempo "Solid."

Dorham and Hope are right with Rollins all the way through, and that takes some doing, because all of the solos are seriously inventive throughout. "Movin' Out" is a succession of rapid-tempo solos, starting with Sonny, and these guys aren't just answering each other, they're answering themselves, playing off their own ideas and finding new directions within each solo. Elmo Hope is the perfect piano player to keep pace and create his own complex improvisations.

In "Swinging for Bumsy," they keep the fire going, ratcheting up the tempo another notch, and this time using short unison bursts to transition from one solo to the next. Art Blakey, due to an equipment malfunction, was playing without his

high-hat cymbals that day, which for a bebop drummer is like a spitball

pitcher being cut off from his slippery elm, but it doesn't slow him down, and he contributes a powerful solo on "Swinging for Bumsy."

In "Swinging for Bumsy," they keep the fire going, ratcheting up the tempo another notch, and this time using short unison bursts to transition from one solo to the next. Art Blakey, due to an equipment malfunction, was playing without his

high-hat cymbals that day, which for a bebop drummer is like a spitball

pitcher being cut off from his slippery elm, but it doesn't slow him down, and he contributes a powerful solo on "Swinging for Bumsy."Hope is deep and expressive on his ballad solo, and it's one of the emotional highlights of the session.

Rollins and Dorham only play one extended unison part, on the "Solid" head, but they're never far apart. They would come together again two years later as part of the revamped Max Roach Quintet, after the death of Clifford Brown.

Dorham and Hope both died young. Hope, one of the most adventurous and experimental players and composers of the bebop era, survived (particularly worthy of mention with today's headlines being what they are) being shot by a cop as a teenager. Throughout much of his life he battled heroin addiction, and it finally beat him. Dorham died of a kidney disease.

I had thought of both Dorham and Hope as sort of second generation beboppers, coming along in the 50s and 60s, but in fact they were both there from the beginning. Dorham joined Mercer Ellington's band in 1945, at age 21, then followed Dizzy Gillespie as the lead trumpeter in Billy Eckstine's famous band, and from there moved on to Gillespie's band. By the time he made these recordings with Sonny Rollins, he had played with Sonny Stitt, Fats Navarro, Lionel Hampton, Mary Lou Williams and J. J.

I had thought of both Dorham and Hope as sort of second generation beboppers, coming along in the 50s and 60s, but in fact they were both there from the beginning. Dorham joined Mercer Ellington's band in 1945, at age 21, then followed Dizzy Gillespie as the lead trumpeter in Billy Eckstine's famous band, and from there moved on to Gillespie's band. By the time he made these recordings with Sonny Rollins, he had played with Sonny Stitt, Fats Navarro, Lionel Hampton, Mary Lou Williams and J. J. Johnson, and had had an extended stint with Charlie Parker.

J. R. Monterose, who played with Dorham on his classic 'Round about Midnight at the Cafe Bohemia album, told me that Dorham was the best leader he had ever played with.

These were released on a 10-inch LP titled Sonny Rollins Quintet featuring Kenny Dorham, and on a 12-inch titled Moving Out, which added the "g" to the first word, and added an extended jam featuring Thelonious Monk.

Saturday, June 06, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 117: Jimmy Raney

Jimmy Raney was last seen in Hackensack with Hall Overton, his Juilliard professor who was also Teddy Charles's mentor. Charles and Overton, to me, represent a school of musical experimentation in the early '50s that falls more or less on the same side of the street as Lennie Tristano, though Raney might not agree with me. Here he is reminiscing about his early days in Chicago:

But here, he's slipping away from those Juilliard/Tristano moorings, and recording a straight-ahead bebop session with Phil Woods, who...uh oh...graduated from Juilliard and studied with Tristano.

But his apprenticeship with Tristano was only six lessons in the summer of 1946, when he was 15, and he learned "that I didn’t know anything and that I had a lot of work to do." And by 1954, he thrown off the mantle of Juilliard, but that's another story, for another blog entry.

This quintet starts its session with a standard, probably a good idea given Weinstock's "no rehearsal" practice, to get their legs under them, and then goes off into three originals, which do get a little farther out, but I loved all of it. It's a session clearly aimed at the album market -- all the tunes are from four to six minutes.

It's the only time Raney ever recorded with Woods, Bill Crow or Joe Morello, although he did do a couple of other sessions with John Wilson. But Morello and Crow were certainly familiar with each other: they were two thirds of the Marian McPartland trio that played at the Hickory House on 52nd Street during the waning years of Swing Street, and they mesh tightly here. In fact, it's hard to say enough about any of the musicians on this gig, but Crow and Morello are always there, the central nervous system.

Something of a surprise here for me is Joe Morello, whom I had always though of as a West Coast musician, but actually, he was mostly an Easterner, born in Springfield, MA, died in Irvington, NJ, 82 years later.

His first major exposure as a musician came at age 9, when he was a featured violinist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but after meeting Jascha Heifetz, he threw in the towel on the violin and switched to drums. When he signed on with McPartland, he was only 25, but already a veteran of the New York scene, having played with Johnny Smith, Gil Melle and Stan Kenton, Sal Salvador. He would leave New York and McPartland in the year after this session to play a short gig on the West Coast -- a scheduled two-month series of dates with a California piano player named Dave Brubeck. Morello accepted Brubeck's offer on a sort of tentative basis. As Brubeck recalled it, Morello said “I’m interested in your group, but your drummer’s out to lunch. I want to be featured.” The New York Times obituary writer adds that "by this, Mr. Brubeck said, Mr. Morello meant that he wanted to be allowed to play solos and experiment." It's safe to say that he got that chance over the next dozen years and some of the most famous drum solos in jazz.

In later years, back on the East Coast, Morello became a noted teacher.

There were no singles, as I've said before, but "Stella by Starlight" and "Back and Blow" were issued as an EP. All four songs were on a ten-inch issued by both New Jazz and Prestige. Later reissues gave leader credit on the session to Phil Woods.

There were a lot of talented young musicians, and they all played bebop. They didn’t get paid for it though. Nobody liked bebop. Not the jazz fans, not the older musicians, not even the Downbeat writers. We mostly played for free in a B-Girl joint on South State Street called the “Say When.” They didn’t like bebop either, but they let us play there to make the place look like a real club, instead of a clip-joint that rolled drunks who were looking for some action...There was another style going on at the time in Chicago. This was the Lenny Tristano style. We boppers didn’t think much of Lenny, and viceversa. As far as I could figure out, nobody liked Lenny’s music except Lee Konitz and his mother. (Lenny’s mother, not Lee’s.) He hated our music and we hated his, and everyone else hated all of us. Lee and Lenny left for New York City soon afterward, so we had the unpopular music scene all to ourselves.It would be nice to think that Lee's mother liked it, too. And I suspect that Raney did, as well. In any event, his style is often compared to that of Tristano acolyte Billy Bauer, and he recorded with another Tristano student, Ted Brown.

But here, he's slipping away from those Juilliard/Tristano moorings, and recording a straight-ahead bebop session with Phil Woods, who...uh oh...graduated from Juilliard and studied with Tristano.

But his apprenticeship with Tristano was only six lessons in the summer of 1946, when he was 15, and he learned "that I didn’t know anything and that I had a lot of work to do." And by 1954, he thrown off the mantle of Juilliard, but that's another story, for another blog entry.

This quintet starts its session with a standard, probably a good idea given Weinstock's "no rehearsal" practice, to get their legs under them, and then goes off into three originals, which do get a little farther out, but I loved all of it. It's a session clearly aimed at the album market -- all the tunes are from four to six minutes.

It's the only time Raney ever recorded with Woods, Bill Crow or Joe Morello, although he did do a couple of other sessions with John Wilson. But Morello and Crow were certainly familiar with each other: they were two thirds of the Marian McPartland trio that played at the Hickory House on 52nd Street during the waning years of Swing Street, and they mesh tightly here. In fact, it's hard to say enough about any of the musicians on this gig, but Crow and Morello are always there, the central nervous system.

Something of a surprise here for me is Joe Morello, whom I had always though of as a West Coast musician, but actually, he was mostly an Easterner, born in Springfield, MA, died in Irvington, NJ, 82 years later.

His first major exposure as a musician came at age 9, when he was a featured violinist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but after meeting Jascha Heifetz, he threw in the towel on the violin and switched to drums. When he signed on with McPartland, he was only 25, but already a veteran of the New York scene, having played with Johnny Smith, Gil Melle and Stan Kenton, Sal Salvador. He would leave New York and McPartland in the year after this session to play a short gig on the West Coast -- a scheduled two-month series of dates with a California piano player named Dave Brubeck. Morello accepted Brubeck's offer on a sort of tentative basis. As Brubeck recalled it, Morello said “I’m interested in your group, but your drummer’s out to lunch. I want to be featured.” The New York Times obituary writer adds that "by this, Mr. Brubeck said, Mr. Morello meant that he wanted to be allowed to play solos and experiment." It's safe to say that he got that chance over the next dozen years and some of the most famous drum solos in jazz.

In later years, back on the East Coast, Morello became a noted teacher.

There were no singles, as I've said before, but "Stella by Starlight" and "Back and Blow" were issued as an EP. All four songs were on a ten-inch issued by both New Jazz and Prestige. Later reissues gave leader credit on the session to Phil Woods.

Monday, June 01, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 116: Billy Taylor

Billy Taylor meshed well with his longtime trio (there seems to be some disagreement as to whether Charlie Smith or Percy Brice was the drummer, but either knew how to play with Taylor), and knew the material he was working with, so it's not surprising that he was able to get about twice as much recording into a single session as the average leader. He did eight tunes here, three standards, a sem-standard (Gordon Jenkins' "Goodbye'), and four originals, all of which were dedicated to disc jockeys and became the theme music for their shows -- Taylor estimated that by the end of the 1950s, he had written themes for at least 15 DJs. Joseph "Tex" Gathings was on WOOK in Washington, DC--primarily a rhythm and blues station, but Tex was strictly a jazz man, although later, in the early 60s, he hosted an all-black teenage dance party on a Washington TV station. Biddy Wood was DJing a jazz show in Philadelphia when Taylor dedicated this song to him, but he was mostly known as a music promoter in Baltimore, and the husband of jazz singer Damita Jo. Eddie Newman was another Philadelphia DJ who also opened his own jazz club. Jim Mendes was perhaps the first black DJ in the Providence-Hartford area, and also hosted a public affairs show for emigres from his native Cape Verde.

As with most of Taylor's early Prestige sessions,

these are hard to find. Nothing on Spotify. "Goodbye." "Lullabye of Birdland" and "Moonlight in Vermont" are all on YouTube. Each features a lush, measured head embellished with plenty of sustain, then moving into bright and increasingly complex right-hand work on the solos.