There's a lot more to say about Donald Byrd, and I'll save most of it, since he would be very active on Prestige before signing an exclusive deal with Blue Note in 1959. But I will mention the quintet he led with Pepper Adams, another Detroiter, from 1958-1961, because it had such a profound effect on me. This would have been 1959, me living in New York for the first time, starting my own transition from scared kid to having an actual sense of myself as a person, with jazz playing a major part in that. And finding my way up to 135th Street, to Smalls Paradise (the picture is from a few years later, when Wilt Chamberlain had bought the club). The Byrd/Adams Quintet was playing there, and there was no minimum, and you could get a beer for 75 cents and nurse it all night. I was still mostly scared kid, and not at all sure I had a right to be there with the real hip cats, but the music drew me in, and I'll never forget it.

There's a lot more to say about Donald Byrd, and I'll save most of it, since he would be very active on Prestige before signing an exclusive deal with Blue Note in 1959. But I will mention the quintet he led with Pepper Adams, another Detroiter, from 1958-1961, because it had such a profound effect on me. This would have been 1959, me living in New York for the first time, starting my own transition from scared kid to having an actual sense of myself as a person, with jazz playing a major part in that. And finding my way up to 135th Street, to Smalls Paradise (the picture is from a few years later, when Wilt Chamberlain had bought the club). The Byrd/Adams Quintet was playing there, and there was no minimum, and you could get a beer for 75 cents and nurse it all night. I was still mostly scared kid, and not at all sure I had a right to be there with the real hip cats, but the music drew me in, and I'll never forget it.That quintet would make several albums, including one live at the Half Note. No live at Smalls, but always in my heart.

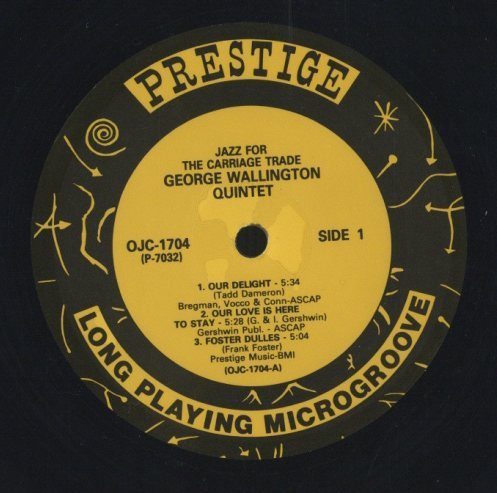

Listening to this album, with George Wallington as leader, is almost as much of a treat as being back at Smalls. It's that good. I'm listening, as always, to the tunes in order of set list for the recording session, not as they appear on the LP, starting with a couple by two important jazz composers. Tadd Dameron is one of the most important, and "Our Delight" is a delight, with some remarkable trade-offs between Woods and Byrd, and maybe even more remarkable piano solos by Wallington. Jazzdisco.com, probably going from the original set list, gives the drummer as Bill "Junior" Bradley, who had been working with the Woody Herman band and was working regularly with Wallington at that time. But the liner notes credit Art Taylor, who was doing a lot of drumming for Prestige in this days, so it's almost certainly him. Ira Gitler explains that although it's Bradley's picture on the album cover (I'll have to take Ira's word for this; I don't know what Bradley looked like, but the picture shows four white guys and Donald Byrd, so that would seem to be the case), he was out of town for the recording date--probably doing a gig with Herman. In any event, the drum fills are very tasty indeed.

The second cut, "Foster Dulles," is not so much a tribute to Eisenhower's secretary of state as a play on the name of its composer, Frank Foster, and thank goodness boppers have not completely forsaken the art of punning on their names. Whoever picked the tunes for this session, Wallington or Weinstock -- and I have to guess it's Wallington, because it's such an eclectic mix -- did a great job.

Gershwin is next, with "Our Love is Here to Stay." It's fascinating to follow the range of composers, noted and obscure, from early 20th Century operetta to Fifties pop, who have caught the attention of modern jazz improvisers. But Gershwin remains the gold standard.

Two Phil Woods compositions suggest, from their titles and from the free-swinging good time music, that these are Rudy Van Gelder's "Five O'Clock Blues." "Together We Wail" is aptly titled, as Byrd and Woods wail together, separately, and closely conjoined., For that matter. so is "But George," which has more Byrd/Woods work, but also allows Wallington a large open space to make the most of.

"What's New" is a showcase ballad for a vocalist, with notable recordings by Linda Ronstadt and Frank Sinatra among others, and I hadn't realized it was written by dixieland bass player Bob Haggart. It makes a fine moody showcase for Wallingford.

1 comment:

Put this on while I was working this afternoon and was immediately blown away by the craftsmanship on display. Don't know why this isn't more well known; if it had Byrd's name on the cover instead of Wallington's I'm sure it'd be highly thought of.

Post a Comment