This is the first of two sessions that would be released by Prestige as Earl Coleman Returns, though what he was returning from, it's hard to say. Probably not the two Gene Ammons sessions that he appeared on, both of which were pretty much buried by Prestige. Perhaps a long-postponed return from his one big success--the 1947 session with Charlie Parker and Errol Garner that brought him his one hit record?

Actually, Earl Coleman never quite returned, never quite went away. His singing style, the rich Mr. B-type baritone, faded in popularity, but he hung on, singing in what one presumes were smaller venues, but always called upon to sing in some pretty distinguished musical settings. When he died in 1995, he received a featured obituary in the New York Times, which is something not given to every veteran jazz musician. including some who one might think of as having made more of a musical impact.

Coleman broke in in 1939, singing with Ernie Fields (he could only have been 14 at the time). The '40s saw him with Jay McShann, Earl Hines, and, interestingly, the Billy Eckstine orchestra, before his 1947 recording debut with Bird, and his one hit, "This is Always." He would also record with Howard McGhee and Fats Navarro.

In the 50s, he also recorded with Sonny Rollins and Elmo Hope, in the 60s with Don Byas (in Paris). with Gerald Wilson, and with Billy Taylor and Frank Foster. In the 8os, he worked and recorded for several years with Shirley Scott.

So what kept him, maybe on the fringes of jazz royalty, but still never far from those fringes, for a lot longer than a lot of the other Eckstine acolytes?

He was very good. And I really started to appreciate how good he was, listening to this session with some much younger musicians (and a veteran rhythm section composed of considerably older musicians--a very interesting group). His sound is very much influenced by Al Hibbler, as well as by Mr. B., and what's probably most important about him is that he works very well with musicians. He doesn't improvise a lot, but he listens to what they're doing, and he gives them a solid ground to solo from. This is true for Farmer and Gryce, and especially true for Jones.

Earl Coleman Returns was made up of this session and another later in 1956, with a smaller group.

No one has posted any of the Earl Coleman Returns tunes on YouTube, so to give you a sample, here he is with Billy Taylor;

Tad Richards' odyssey through the catalog of Prestige Records:an unofficial and idiosyncratic history of jazz in the 50s and 60s. With occasional digressions.

Showing posts with label Oscar Pettiford. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Oscar Pettiford. Show all posts

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

Wednesday, September 16, 2015

Listening to Prestige Part 145: Miles Davis

This is an interesting period in Miles's career. This session was recorded in June of 1955, and he was still working with Bob Weinstock's philosophy:

In July, he played the Newport Jazz Festival with an all-star group, including Thelonious Monk, although they would never record together after the December dustup. The rest of the group was Gerry Mulligan, Zoot Sims, Percy Heath and Connie Kay, who had just joined the Modern Jazz Quartet to replace expatriate-to-be Kenny Clarke. Miles doesn't appear to have been a part of the official festival lineup, but Columbia producer George Avakian heard him and his group jamming on Monk's "Round Midnight," and immediately recruited him for Columbia. Avakian had exactly the opposite to Weinstock's philosophy. He wanted Miles to put together a regular and recognizable group. Avakian's idea turned out to be the stroke of genius that put Miles over the top, but we can only be grateful, as well, for Weinstock's "jam with Miles" sessions.

It appears that, without necessarily planning it that way, Miles was already assembling that regular group. Oscar Pettiford wouldn't remain--reportedly his personality clashed with Miles's--but Red Garland and Philly Joe Jones would.

Jones had only recorded once before with Miles, but the two had spent time on the road together during Miles's self-imposed exile from New York. Garland had played on various dates with Billy Eckstine, Roy Eldridge, Coleman Hawkins, Charlie Parker, Lester Young and Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson (John Coltrane was also in Vinson's band), but he was pretty much unknown when Miles tapped him. They had boxing in common as well as music--Garland, as a welterweight, had actually fought Sugar Ray Robinson.

Ira Gitler, in preparing the liner notes for the Prestige album from this session, talked to Miles about musicians he admired. This must have been after Newport, so Miles must already have been thinking about who he wanted in the group he'd be forming.

He recorded a few times with Dizzy Gillespie, first on a 1945 session with Charlie Parker, but Diz mostly played piano on that session. He was supposed to strictly play piano, but the youthful Miles was so nervous about playing with his idols that he broke down completely on "Ko-Ko," and Dizzy had to step in. He played in a trumpet session with Dizzy and Fats Navarro in 1949. Fats was gone, of course, by the 1955 conversation with Gitler. This was the 1949 edition of the Metronome Allstars, a group of Metronome Magazine's poll-winners that was gathered for a recording annually throughout most of the Forties and well into the 50s. Metronome would gather together as many of the poll winners as they could, and fill in the rest with runners-up. 1949's group was more than a little impressive: Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro (trumpet); J.J. Johnson, Kai Winding (trombone); Buddy DeFranco (clarinet); Charlie Parker (alto saxophone); Charlie Ventura (tenor saxophone); Ernie Caceres (baritone saxophone); Lennie Tristano (piano); Billy Bauer (guitar); Eddie Safranski (bass); Shelly Manne (drums). There was another session with Bird in 1953, and then nothing until 1989, where they appeared as the trumpet session on a very strange Quincy Jones recording that features vocals by Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and rappers Big Daddy Kane and Kool Moe Dee. I'm not certain it's an entirely successful experiment, but I'm sure as hell not certain it isn't.

But he wasn't looking for another trumpet player to round out his new quintet. He was looking for a tenor sax, and actually, Sonny Rollins was his first choice. Rollins played with the new quintet in July, right after Newport, but the arrangement wasn't to last. Sonny had his own heroin habit to kick. John Coltrane was not yet on Miles's radar. Hank Mobley would play with the quintet, but not until years later.

Miles would use Ray Bryant on piano a month later, in another one of his Prestige pickup groups, but

Red Garland was to be his man. At the time of this recording, and this interview, Garland was the least-known of the piano men that Miles admired--even including Carl Perkins, who would die too young to establish much more of a reputation, and who really did play bass notes with his elbow, his left arm having been crippled by polio. But Miles clearly had his eye on Garland already.

When you think of answer songs, you're more likely going to think of country ("It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels") or rock ("Sweet Home Alabama" answering Neil Young's "Southern Man," and then Warren Zevon's "Play it All Night Long" answering Lynyrd Skynyrd), or even blues (Rufus Thomas's "You Ain't Nothin' But a Bearcat"). But here's one turning up in jazz: Miles's "I Didn't" as an answer to Monk's "Well You Needn't" (a tune that Miles also recorded). "I Didn't" is sharp, crisp and sardonic. You have to be awfully good to take on the premier composer of his generation, but Miles is up to the task.

"A Night in Tunisia" is one of the most famous of all bebop standards, and "Green Haze" a Davis original that showcases Garland, his new piano discovery. The others are all odd choices that Miles puts his indelible stamp on. "Will You Still Be Mine" was written by pop singer and swing era tunesmith Matt Dennis. The other two are by composer Arthur Schwartz, and were both songs that one would not have chosen to be present at the birth of the cool, or even at its confirmation. "I See Your Face Before Me" was best known in versions by Guy Lombardo and Glen Gray. Coltrane and Brubeck would both record it later.

"I've Got a Gal in Calico," written by Schwartz and Leo Robin for a movie musical, is one of those completely cornball, white-bread numbers, like "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," that no one could consider as the basis for a hipster jazz improvisation. But Miles worked the same magic with "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," didn't he?

"I've Got a Gal in Calico," written by Schwartz and Leo Robin for a movie musical, is one of those completely cornball, white-bread numbers, like "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," that no one could consider as the basis for a hipster jazz improvisation. But Miles worked the same magic with "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," didn't he?

Both "Green Haze" and "A Night in Tunisia" were released as two-sided 45s. The Musings of Miles became Davis's first 12-inch LP, Prestige PRLP 7007. Before it were two reissues, PRLP 7004, Lee Konitz With Tristano, Marsh And Bauer, from four sessions (1/11/49, 6/28/49, 9/27/49, 4/7/50) in 1949-50; and PRLP 7006, Mulligan Plays Mulligan (original session 8/27/51). In between was an MJQ session recorded after Miles, but released before.

So, our basic idea was just to make records with different people, to record with the best people around...we would sit down and talk about it. Miles would mention who was in town, who he would like to record with. I'd say who I'd like to hear him record with.That was about to change. Miles was healthy by this time, free from heroin addiction, working out regularly. Although he did not mix it up with Thelonious Monk during their session of the previous December, as was rumored at the time, he was working out in the gym regularly, including sessions on the light punching bag.

In July, he played the Newport Jazz Festival with an all-star group, including Thelonious Monk, although they would never record together after the December dustup. The rest of the group was Gerry Mulligan, Zoot Sims, Percy Heath and Connie Kay, who had just joined the Modern Jazz Quartet to replace expatriate-to-be Kenny Clarke. Miles doesn't appear to have been a part of the official festival lineup, but Columbia producer George Avakian heard him and his group jamming on Monk's "Round Midnight," and immediately recruited him for Columbia. Avakian had exactly the opposite to Weinstock's philosophy. He wanted Miles to put together a regular and recognizable group. Avakian's idea turned out to be the stroke of genius that put Miles over the top, but we can only be grateful, as well, for Weinstock's "jam with Miles" sessions.

It appears that, without necessarily planning it that way, Miles was already assembling that regular group. Oscar Pettiford wouldn't remain--reportedly his personality clashed with Miles's--but Red Garland and Philly Joe Jones would.

Jones had only recorded once before with Miles, but the two had spent time on the road together during Miles's self-imposed exile from New York. Garland had played on various dates with Billy Eckstine, Roy Eldridge, Coleman Hawkins, Charlie Parker, Lester Young and Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson (John Coltrane was also in Vinson's band), but he was pretty much unknown when Miles tapped him. They had boxing in common as well as music--Garland, as a welterweight, had actually fought Sugar Ray Robinson.

Ira Gitler, in preparing the liner notes for the Prestige album from this session, talked to Miles about musicians he admired. This must have been after Newport, so Miles must already have been thinking about who he wanted in the group he'd be forming.

I asked Miles who his current favorites were. On his own instrument he quickly named Art Farmer and Clifford Brown as the new stars and Kenny Dorham as one who has come into his own. Then he spoke lovingly of Dizzy Gillespie. "Diz is it, whenever I want to learn something I go and listen to Diz." In the piano department two Philadelphia boys, Red Garland (heard to good advantage in this LP) and Ray Bryant were mentioned along with Horace Silver, Hank Jones, and Carl Perkins, "a cat on the Coast who ploys bass notes with his elbow'. The talk shifted to saxophone and to Sonny Rollins and Hank Mobley who are carrying on the tradition of Charlie Parker. This naturally started us talking about Bird. Miles credited his most wonderful experiences in jazz to his years with Bird. He stared slowly ahead *Like Max said, New York isn't New York anymore without Bird." Max's name being mentioned directed the conversation to drummers. "Art Blakey and Philly Joe Jones; Max For brushes." Miles is very conscious of drummers. Many times he will sit down between the drummer and bass player and just listen to what the drummer is doing.Miles did actually play with Kenny Dorham once, in a 1949 all-star big band in Paris, Le Festival International de Jazz All-Stars.

He recorded a few times with Dizzy Gillespie, first on a 1945 session with Charlie Parker, but Diz mostly played piano on that session. He was supposed to strictly play piano, but the youthful Miles was so nervous about playing with his idols that he broke down completely on "Ko-Ko," and Dizzy had to step in. He played in a trumpet session with Dizzy and Fats Navarro in 1949. Fats was gone, of course, by the 1955 conversation with Gitler. This was the 1949 edition of the Metronome Allstars, a group of Metronome Magazine's poll-winners that was gathered for a recording annually throughout most of the Forties and well into the 50s. Metronome would gather together as many of the poll winners as they could, and fill in the rest with runners-up. 1949's group was more than a little impressive: Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro (trumpet); J.J. Johnson, Kai Winding (trombone); Buddy DeFranco (clarinet); Charlie Parker (alto saxophone); Charlie Ventura (tenor saxophone); Ernie Caceres (baritone saxophone); Lennie Tristano (piano); Billy Bauer (guitar); Eddie Safranski (bass); Shelly Manne (drums). There was another session with Bird in 1953, and then nothing until 1989, where they appeared as the trumpet session on a very strange Quincy Jones recording that features vocals by Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and rappers Big Daddy Kane and Kool Moe Dee. I'm not certain it's an entirely successful experiment, but I'm sure as hell not certain it isn't.

But he wasn't looking for another trumpet player to round out his new quintet. He was looking for a tenor sax, and actually, Sonny Rollins was his first choice. Rollins played with the new quintet in July, right after Newport, but the arrangement wasn't to last. Sonny had his own heroin habit to kick. John Coltrane was not yet on Miles's radar. Hank Mobley would play with the quintet, but not until years later.

Miles would use Ray Bryant on piano a month later, in another one of his Prestige pickup groups, but

Red Garland was to be his man. At the time of this recording, and this interview, Garland was the least-known of the piano men that Miles admired--even including Carl Perkins, who would die too young to establish much more of a reputation, and who really did play bass notes with his elbow, his left arm having been crippled by polio. But Miles clearly had his eye on Garland already.

When you think of answer songs, you're more likely going to think of country ("It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels") or rock ("Sweet Home Alabama" answering Neil Young's "Southern Man," and then Warren Zevon's "Play it All Night Long" answering Lynyrd Skynyrd), or even blues (Rufus Thomas's "You Ain't Nothin' But a Bearcat"). But here's one turning up in jazz: Miles's "I Didn't" as an answer to Monk's "Well You Needn't" (a tune that Miles also recorded). "I Didn't" is sharp, crisp and sardonic. You have to be awfully good to take on the premier composer of his generation, but Miles is up to the task.

"A Night in Tunisia" is one of the most famous of all bebop standards, and "Green Haze" a Davis original that showcases Garland, his new piano discovery. The others are all odd choices that Miles puts his indelible stamp on. "Will You Still Be Mine" was written by pop singer and swing era tunesmith Matt Dennis. The other two are by composer Arthur Schwartz, and were both songs that one would not have chosen to be present at the birth of the cool, or even at its confirmation. "I See Your Face Before Me" was best known in versions by Guy Lombardo and Glen Gray. Coltrane and Brubeck would both record it later.

"I've Got a Gal in Calico," written by Schwartz and Leo Robin for a movie musical, is one of those completely cornball, white-bread numbers, like "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," that no one could consider as the basis for a hipster jazz improvisation. But Miles worked the same magic with "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," didn't he?

"I've Got a Gal in Calico," written by Schwartz and Leo Robin for a movie musical, is one of those completely cornball, white-bread numbers, like "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," that no one could consider as the basis for a hipster jazz improvisation. But Miles worked the same magic with "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," didn't he?Both "Green Haze" and "A Night in Tunisia" were released as two-sided 45s. The Musings of Miles became Davis's first 12-inch LP, Prestige PRLP 7007. Before it were two reissues, PRLP 7004, Lee Konitz With Tristano, Marsh And Bauer, from four sessions (1/11/49, 6/28/49, 9/27/49, 4/7/50) in 1949-50; and PRLP 7006, Mulligan Plays Mulligan (original session 8/27/51). In between was an MJQ session recorded after Miles, but released before.

Sunday, January 04, 2015

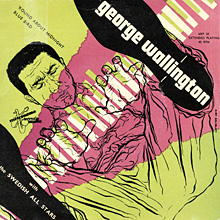

Listening to Prestige Records Part 65: George Wallington

How hard is it to be a jazz musician? George Wallington was one of the original beboppers, one of the most respected and sought-after bebop piano players, and in 1960, worn down by the grind and the constant scuffling for money, he quit to go into the family's air conditioning business. And he was lucky to have a family business to go into. Who knows how many other great musicians of this era would have made the same choice, had they been able to? Who knows for how many heroin was an alternative to the family air conditioning business?

Wallington was retired from music for a quarter century, finally returning in 1984 to record three albums before he died in 1993.

In 1952, Wallington was 28 years old and a veteran of the jazz world. He had been a part of the first band that Dizzy Gillespie brought to 52nd Street, in 1944. And even then, at 19, he was a seasoned veteran. He had grown up in an Italian immigrant family (his birth name was Giacinto Figlia - "Wallington" was a schoolyard nickname because he dressed like a British swell). His father had introduced him to opera, and gotten him started on piano and solfeggia (sight singing); Lester Young (heard on the radio with Count Basie's band) inspired him to turn to jazz. By 16 he was playing in clubs in New York, including a spot called George's, where he accompanied Billie Holiday.

About that first bebop gig with Dizzy, at the Onyx Club, Wallington said:

Max Roach said of Wallington'a role in that first band at the Onyx that his great virtue was knowing how to stay out of the way.

Speaking of romanticism and "Tenderly," here's a story told to me by the great pop singer Margaret Whiting, who was a close friend when I lived in New York in the 70s. She and songwriter Walter Gross had been an item, but she'd had to break it off because of his drinking. But then one night he showed up at her house about two int he morning, drunkenly banging on her door and demanding to be let in. She had no choice - she opened the door before he could wake the whole neighborhood.

He confronted her: "You fucking bitch...you ruined my life, you fucking cunt. So I came by to tell you just what I thought of you, you fucking bitch." He staggered over to the piano. "I wrote this to show you what I think of you, you fucking bitch." And he played "Tenderly."

Margaret was a romantic, but also a realist. She got some coffee into him, and immediately called...who but a lyricist? Jack Lawrence came over, and they finished the song.

On the first of these sessions, Chuck Wayne joins the group on mandola, which is an unusual instrument -- slightly larger than a mandolin, it bears the same relation to a mandolin that the viola has to the violin. It's also an unusual instrument for a bebop ensemble in that it uses the same tuning as the tenor banjo, an instrument associated with the early Dixieland bands.

But Wayne was an unusual jazz guitarist -- for one thing, he may well have been the only jazz guitarist ever to play the banjo on bebop recordings.. Like Wallington, he was the son of immigrant parents (Czech, in his case -- he was born Charles Jagelka), and his musical start was playing the mandolin in a balalaika band.

He had switched to jazz, and to the guitar, by the time he met George Wallington. They were both playing in a Dixieland group led by Joe Marsala, and Wallington introduced him to bebop. They're a good pairing on these quartet sessions.

And tossing this in -- Wallington composed "Godchild," one of the tunes on Birth of the Cool.

The trio and quartet sessions were all released on 78, and all on the same 10-inch LP (as George Wallington Trio).

Wallington was retired from music for a quarter century, finally returning in 1984 to record three albums before he died in 1993.

In 1952, Wallington was 28 years old and a veteran of the jazz world. He had been a part of the first band that Dizzy Gillespie brought to 52nd Street, in 1944. And even then, at 19, he was a seasoned veteran. He had grown up in an Italian immigrant family (his birth name was Giacinto Figlia - "Wallington" was a schoolyard nickname because he dressed like a British swell). His father had introduced him to opera, and gotten him started on piano and solfeggia (sight singing); Lester Young (heard on the radio with Count Basie's band) inspired him to turn to jazz. By 16 he was playing in clubs in New York, including a spot called George's, where he accompanied Billie Holiday.

About that first bebop gig with Dizzy, at the Onyx Club, Wallington said:

Dizzy used to take me to his house and we'd play and he showed me his songs. Then he and Oscar Pettiford started the band at the Onyx. Charlie Parker was supposed to join us but he couldn't get a cabaret card. Anyway we had Don Byas, then Lester Young. Billie Holiday used to sing with us sometimes and Sarah Vaughan used to come in too.OK, this is why, when anyone asks me "If you could go back in time to another era, what would it be?" my answer is always the same. New York, 1940s. 52nd Street, Minton's, Monroe's.

I don't know if we thought of what we were doing at the Onyx as something historic, but we did know we were doing something new and that no one else could play it.

Max Roach said of Wallington'a role in that first band at the Onyx that his great virtue was knowing how to stay out of the way.

We didn't need a piano player [like Bud Powell] to show us the way to go. Piano players up to that point played leading chords. We didn't do that because we were always evolving our own solo directions. We needed a piano player to stay outta the way. The one that stayed outta the way best was the best for us. That's why George Wallington fitted in so well with us, because he stayed outta the way, and when he played a solo, he'd fill it up; sounded just like Bud.Leading his own group, Wallington didn't need to stay outta the way, and Roach was still propelling him on, and the sidemen on these two sessions give some idea of how much respect Wallington had garnered by this time -- even from Oscar Pettiford, whom Roach remembers as not being entirely won over by Wallington when the Onyx Club gig came together:

Every now and then, George would miss a chord, and Oscar would jump all over him, "White muthafucka can't play -- shit!" I had to spend a lot of time protecting him from Oscar."Sounded just like Bud" is something you hear a lot in discussions of George Wallington. They were two of the most important pianists in the development of bebop -- and, Wallington's ability to stay outta the way notwithstanding, two of the most accomplished and daring virtuosi. But there's a lot of difference, too. Wallington's early classical training shines through, and you can hear the sorts of romantic flourishes you'd associate with a Vladimir Horowitz. But when Wallington takes on an unabashedly romantic tune like "Laura" or "Tenderly," those same flourishes become dry, ironic, brilliantly anti-romantic.

Speaking of romanticism and "Tenderly," here's a story told to me by the great pop singer Margaret Whiting, who was a close friend when I lived in New York in the 70s. She and songwriter Walter Gross had been an item, but she'd had to break it off because of his drinking. But then one night he showed up at her house about two int he morning, drunkenly banging on her door and demanding to be let in. She had no choice - she opened the door before he could wake the whole neighborhood.

He confronted her: "You fucking bitch...you ruined my life, you fucking cunt. So I came by to tell you just what I thought of you, you fucking bitch." He staggered over to the piano. "I wrote this to show you what I think of you, you fucking bitch." And he played "Tenderly."

Margaret was a romantic, but also a realist. She got some coffee into him, and immediately called...who but a lyricist? Jack Lawrence came over, and they finished the song.

On the first of these sessions, Chuck Wayne joins the group on mandola, which is an unusual instrument -- slightly larger than a mandolin, it bears the same relation to a mandolin that the viola has to the violin. It's also an unusual instrument for a bebop ensemble in that it uses the same tuning as the tenor banjo, an instrument associated with the early Dixieland bands.

But Wayne was an unusual jazz guitarist -- for one thing, he may well have been the only jazz guitarist ever to play the banjo on bebop recordings.. Like Wallington, he was the son of immigrant parents (Czech, in his case -- he was born Charles Jagelka), and his musical start was playing the mandolin in a balalaika band.

He had switched to jazz, and to the guitar, by the time he met George Wallington. They were both playing in a Dixieland group led by Joe Marsala, and Wallington introduced him to bebop. They're a good pairing on these quartet sessions.

And tossing this in -- Wallington composed "Godchild," one of the tunes on Birth of the Cool.

The trio and quartet sessions were all released on 78, and all on the same 10-inch LP (as George Wallington Trio).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)