LISTEN TO ONE: Denise

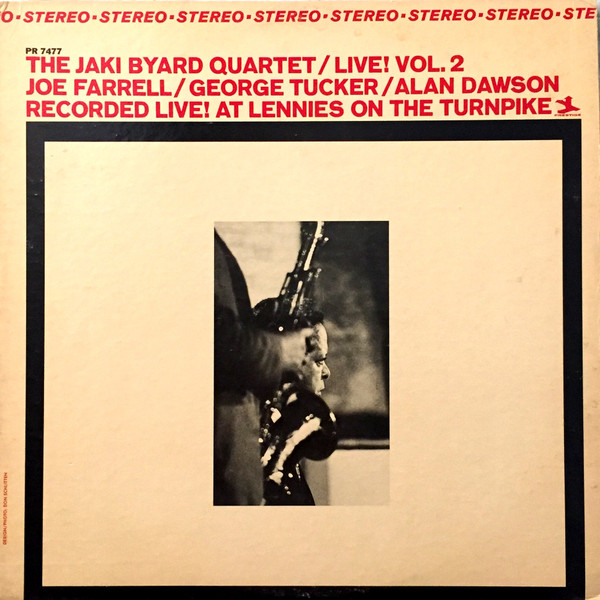

I talked from time to time about swing-to-bop, in writing about the early days of Prestige, and artists like Zoot Sims. It may be time to consider a new kind of transitional music -- perhaps we should call it straight-ahead-to-free. I don't know what else to call this marvelous live album by Jaki Byard, except perhaps to add that its genesis seems to blossom from Charles Mingus and Earl Hines. To explain that, I'll have to quote extensively fron the liner notes to the original album, by the incomparable Ira Gitler.

Gitler desdribes a night when Don Schlitten came to hear two groups who were sharing the stage at the Village Vanguard--Mingus and Hines. Byard was playing with Mingus then, and he approached Schltten with an idea. Lennie Sogoloff, of the small but well-regarded north-of-Boston jazz club, Lennie's on the Turnpike, had heard Jaki's work on Booker

Ervin's The Freedom Book album, annd he wanted Jaki to bring the trio he had used to back up Ervin--Richard Davis and Alan Dawson. Dawson was a Boston resident, and Sogoloff had already line him up.

Jaki, in turn, asked Schlitten if Prestige would like to record on the spot,

Don was immediately in favor of the idea and put his creative brain to work helping to shape the date. Since Davis was unable to leave New York at the time, he suggested George Tucker, then playing bass with Hines. Byard liked this and suggested multi-reed man Joe Farrell...Unwilling to trust the unknown, Schitten decided to employ a New York engineer...Dick Alderson was his man.

The group opened on a Monday. By Thursday, when Schlitten and Alderson arrived...the four men were really getting it together...Byard told [Don] they were ready. This was an understatement. Schlitten describes it as "One of the most beautiful experiencesI've ever had in listening to jazz."

I wouldn't argue with him.

It is interesting to note that the inception of this recording came at a time when Jaki was playing opposite Earl Hines. "Out of all the bands," [Byard has said], "The only one I used to dig was...Fatha Hines. That was the only band that intrigued me."

The Mingus-Hines week at the Vanguard was an inspirational one for Byard...Hines plays as if he is a big band, [and] it seemed to inspire Byard to emphasize his own leanings in this direction when he got to Lennie's. "I never heard Jaki play this way," says Schlitten. "He was like a 16-piece band. One second he would be playing the piano part, and then he would resolve and sound like a saxophone section. Behind Joe Farrell he became a punching trumpet section. Throughout the whole thing he was a bandleader. Here was a quartet that sounded like three times that many."

...For all the rough edges involved in such a mercuarial improvising process, there is nothing "haphazard." Even when they go "outside" -- and Jaki knows what he is doing when he is "out there" -- they are always under the firm control of the leader who is able to bring everything and everyone back "inside" to a logical, satisfying conclusion.

Schlitten recalls how the people at Lennie's were completely taken with Byard's ability to capture the entire history of jazz piano playing, (As he has made clear before, Jaki does not fool around in the various styles he is capable of adopting. He does not parody but instead transmits the "feeling" of the greats that he is able to embody as well.) ...Don states, "he runs the gamut from Scott Joplin, James P., Fats, Basie, Duke, to Garner, Bud, Bill Evans, Monk..." He also does the things that Brubeck and Cecil Taylor each try to do but either fall short or don't know when to stop.

Ira Gitler is, of course, one of the great jazz writers of his era, but he is of his era, and it's now a half century since he wrote this, and times change, and tastes change, and perspectives change. Gitler could be forgiven if his attitudes, and his critical perspective, had fallen somewhat out of step with today's tastes.

And maybe they have. Maybe mine have. We live in a time when some young critics reject all of Coltrane's early work as being hokey and not worth listening to...and I mean, even Giant Steps.

But I don't buy that, nor do I think it's a universally held opinion. We also live in a time when young jazz musicians study their craft in college and are denigrated for that, often unfairly, and grow up with a respect for the totality of jazz.

So I'm going to continue to do the only thing I can do, which is to consider my 21st century perspective, and my judgment of Ira Gitler in 1965, to be a valid one, and continue from there.

What's remarkable is how spot-on Gitler was, even about Jaki Byard vis-a-vis Dave Brubeck and Cecil Taylor. Listening to Byard today, you can still hear what Gitler heard, and even putting into the context of a lot more years and a lot more music, Gitler is still right -- he always knew what he was doing when he was "out there," and he knew when and how to bring it back "inside." And it wasn't because he chickened out, and wouldn't stay as far "out there" or as long "out there" as Cecil Taylor or Albert Ayler. It's because he heard it all, and wanted it all, and found a way to include it all.

And all of this leads me, in 2023, in a post-postmodern age, an age informed by the conservatorship of Wynton Marsalis and Jazz at Lincoln Center and jazz goes to college and jazz meets rock and electronica and more jazz in heaven and earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy, to wonder why Jaki Byard, who encompassed all of it, and always with vision, and always with soul, is so underappreciated? If you look at the internet lists of greatest jazz pianists, lists made up by people who range in age from younger than me to ridiculously younger that me, where is he? Ranker, which is entirely based on fan voting and boasts over 8.7K voters, has Byard not included at all in a list of 70 names. The uDiscover list, compiled by" a team of respected authors and journalists who are passionate about what they do, with decades’ worth of experience in print, online, radio and TV journalism," does have him in the top 50, at number 41. But to the general public -- the general jazz-listening public, that is, the Ranker public, which knows enough to vote Art Tatum number one and Oscar Peterson number two, he doesn't exist.

Listen to what the man does. Start with my Listen to One, then check out the rest of this album, which you can find on YouTube but not on Spotify. Then listen to more.

On my last blog entry, I castigated those long-ago record company owners (visionaries all, who don't deserve my castigation except in this case) for only recording Andy and the Bey Sisters three times during their eleven years as a team. Fortunately, Jaki Byard did not suffer the same fate. Bob Weinstock stayed with him. This is his tenth appearance on Prestige, his fourth as leader of his own group. He would record six more albums as leader, and 23 more for other, mostly smaller labels up through 1998. On Prestige alone, he recorded with Don Ellis, Eric Dolphy and Booker Ervin; on other labels, with Maynard Ferguson, Quincy Jones, Roland Kirk, and others. And of course, most famously with Charles Mingus (13 albums).

He was with Prestige pretty much right up to the end, so I'll keep coming back to him. And there'll be more to say, since he wasn't much for repeating himself.

These were released as The Jaki Byard Quartet - Live! Vol. 1 (1965) and Vol. 2 (1967). One cut, "Spanish Tinge," was included on a 1967 studio album, On the Spot. And several previously unissued cuts -- the alternate take of "Twelve," "Dolphy" numbers 1 and 2, "St. Mark's Place Among The Sewers," plus Jaki's Ballad Medley which had been on Volume 2, were released in 2003 under the Prestige label, although by that time Prestige was a part of Fantasy and about to be bundled into the Concord group, as The Last From Lennie's, so someone still remembered Jaki in the 21st century (he died in 1999). Don Schlitten produced.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2941299-1310511138.jpeg.jpg)