LISTEN TO ONE: Carnival Samba

It's been noted that one of the most remarkable things about jazz in the 20th century was the rapidity with which it morphed and transfigured itself. The progression from folk art to popular art to high art is common to almost all modes of expression, but with jazz the creative explosions and transfigurations happened with dizzying speed. Previous genres had no time to die out before their successors, and their successors' successors, grew from liminality to full flower. In mid-century New York City, it was possible to hear early New Orleans jazz from artists like Bunk Johnson and Baby Dodds, and of course Louis Armstrong when he was not off on a world tour as ambassador of American culture. Clubs like the Metropole Cafe and

Eddie Condon's thrived through the mid-1960s (Metropole) and even the mid-1970s (Condon's). The swing era was widely represented, with artists like the Dorsey Brothers and Benny Goodman playing venues like the Rainbow Room and the Roseland Ballroom, Count Basie at Birdland (and his style of music represented at Count Basie's in Harlem), Coleman Hawkins playing the Village Vanguard and the Village Gate. Rhythm and blues could be heard at the Apollo, and at Alan Freed's rock 'n roll shows, where his house band was led by jazzmen like Al Sears and Sam "the Man" Taylor. Bebop was everywhere, and soul jazz and free jazz and Latin jazz all had their venues,

Small wonder that a younger generation of musicians had a veritable smorgasbord of styles to choose from, and some chose to graze up and down, sampling here and there. A young Ray Bryant would play traditional jazz in the afternoon at the Metropole with Henry "Red" Allen, then head downtown to play with the moderns in the evening. Steve Lacy skipped right over the prevailing sounds of his own era, starting with trad jazzers like Allen, Zutty Singleton, Buck Clayton and Jimmy Rushing, and then moving straight into the avant garde with Cecil Taylor.

Dave Pike was another. Always a confessed bebopper at heart, he had a restless spirit that responded to restless times, and he experimented over a range of musical styles. Born in Detroit in 1938, he was not to become a part of that still-fertile musical scene, as his family moved to Los Angeles when he was fourteen. He had begun playing the drums at age 8. Inspired by Lionel Hampton and especially by Milt Jackson, he gravitated toward the vibes, and by the time he was in his late teens, he was playing with West Coast musicians like Curtis Counce, Dexter Gordon and Harold Land.

His first recording, however, was with avant gardist Paul Bley, in 1958. In 1961, after a move to the East Coast, he made his first recording as leader, and as proof that you can't altogether take Detroit out of the boy, Barry Harris was his piano player. This was a bebop session, with Harris and such bebop standards as "Green Dolphin Street" and "Hot House." A second album, for Columbia's Epic subsidiary, featured Bill Evans on piano and more straight ahead jazz.

By this time he had begun playing with Herbie Mann, whose group featured a lot of Latin music, so when he signed with Prestige in 1962, that became the focus of his work,

Brazilian music was the hot Latin sound at that time, and Antonio Carlos Jobim was the hot composer. Pike elected to go in a different direction, turning to another composer, one who was renowned in Brazil but whose reputation had not made the leap to the northern hemisphere. Joao Donado had worked with both Jobim and Joao Gilberto, but he perhaps got a little too experimental, and his popularity in Brazil started to decline as people complained they couldn't dance to his music. Relocating to the US, he played with Mongo Santamaria, Tito Puente, Bud Shank, and Cal Tjader, and had some minot hits for Sergio Mendes, and a handful of songs fairly widely recorded by Latin bands, but he never did make that big time status reached by Jobim and Gilberto.

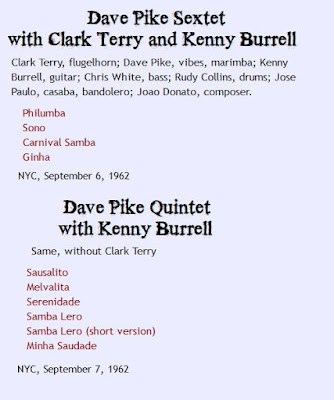

Pike and his group spent two days out at Englewood Cliffs, the first of which seems to have not been a complete success, in spite of having Clark Terry in the group. Two tunes, "Samba Lero" and "Serenidade," were rejected, and re-recorded the next day without Terry.

The other headliner, Kenny Burrell, was there for both days, as were the rest of the musicians.

Rudy Collins had made his Prestige debut a couple of weeks earlier, with Ahmed Abdul-Malik. He would play on a few more Prestige sessions over the decade, but was mostly known for his work with Dizzy Gillespie and Herbie Mann.

This was Chris White's only Prestige recording, but not his only bossa nova recording, and not his only bossa nova recording in 1962. In June, he had recorded bossa nova albums with Lalo Schifrin for Audio Fidelity and with Quincy Jones for Mercury. In September, he was called back to finish the Quincy Jones project, and in October, more bossa nova with Schifrin for MGM. White was one of those young players, like Pike, Bryant and Lacy, who was drawn to different schools of jazz. He worked with Cecil Taylor in the 1950s, then with Nina Simone, and then for several years with Dizzy Gillespie. He also had a distinguished career as an educator, where one imagines his open-minded approach to musical schools must have stood him in good stead.

Brazilian percussionist Jose Paolo also played the two Lalo Schifrin recording date, and recorded with Stan Getz. He also recorded a couple of albums under his own name for a budget label, Evon.

The album was released on New Jazz as Bossa Nova Carnival -- Dave Pike Plays The Music Of Joao Donato With Clark Terry And Kenny Burrell. "Samba Lero" and "Melvalita" were released on 45, with an interesting twist. Instead of just editing down the album cut to 45 RPM length, they recorded "Samba Lero" twice, a full length version and a 45 version. They also seem to have recorded a third version with vocals, which was not released. There's no mention of a vocalist on the session log, so I'm guessing it was probably Pike, who was known to vocalize -- and dance -- along with his solos. No second version of "Melvalita."

Elliot Mazer produced. Mazer's family were neighbors of Bob Weinstock's in Teaneck, NJ, and Weinstock first hired him as a gofer, gradually working him into the music end. Mazer would go on to be a successful producer of pop and rock acts, most notably with a long association with Neil Young. This was one of the few Prestige studio albums not recorded by Rudy Van Gelder.

:format(webp):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-3060866-1339586709-2356.jpeg.jpg)