LISTEN TO ONE: Chasin' The Bird

This is McPherson's second Prestige album, and he hasn't lost his love for pure bebop. In fact, he never did, and although he may have seemed a little retro in 1965, both he and his mentor Barry Harris came to be recognized as national treasures for keeping alive the inventive musical style brought to life by McPherson's hero, Charlie Parker.

In a 2019 80th birthday tribute to twin octogenarians McPherson and McCoy Tyner at Lincoln Center, Jazz at Lincoln Center's also saxophonist Sherman Irby paid this tribute: “The bebop master is a true alto saxophonist. He plays the instrument with fire, passion and precision. He can pull your heartstrings with one note, and dazzle you with virtuosity and

imagination. There is only one Bird, one Stitt, one Cannonball—and one Charles McPherson.”

In 2020, McPherson laid to rest the old canard that you can't dance to bebop with a striking new album. Jazz Dance Suites, which led the British jazz blog Bebop Spoken Here to enthuse:"Magnificent sounds somewhat inadequate! I doubt there will be a better album released this year. It is just so listenable, so danceable, so everything …"

And Mark Stryker, writing about his 2024 release, Reverence, said "More than six decades into a remarkable career, few command and deserve our reverence quite like Charles McPherson.”

So...in 1965, they may not have been talking about McPherson as the newest sound in town, but he was making music that people still wanted to hear, as evidenced by his six Prestige albums in four years -- and as evidenced by the fact that over six decades, he has never been far from the recording studio.

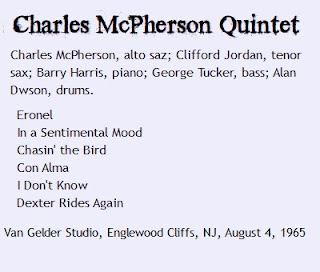

And if this session doesn't exactly bring you back to 1965, it does something much more important--it brings you into the heart of jazz. McPherson has assembled a cohesive group with Clifford Jordan joining him as his companion saxophonist, Harris on piano, George Tucker on bass, and Alan Dawson on drums.

They tip their hats to the progenitors of bebop, with compositions by Charlie Parker ("Chasin' the Bird"), Dizzy Gillespie ("Con Alma:), Thelonious Monk ("Eronel") and Dexter Gordon/Bud Powell ("Dexter Rides Again"). There's one original composition, "I Don't Know."

It's hard, from a distance of years, to imagine the reception McPherson got in 1965. Was McPherson irrelevant? Was he trying to pretend it was still 1955, or even 1945? Or was he a refreshing antidote to the dumbing down of bebop by the soul jazzers, or the incomprehensible navel-gazing of the free spirits?

It's hard to imagine from a perspective of today's listeners, for most of whom what 1945, 1955 and 1965 have in common is that they all happened before they were born. No one is likely to sit down on a rainy afternoon and play, in succession, albums by Jack McDuff, Albert Ayler and Charles McPherson. Conversely, not many contemporary listeners are going to listen to a few bars of Con Alms, rip it off the turntable (my imagined listener is a technological purist), say "What is this shit? Give me the real thing!" and put on a 78 of Bird on Dial.

Today it's just the music, and interpretations of Bird, Diz, Monk, Duke and Dexter, if they're played by someone good, are going to sound good, which is the best you can hope for from a piece of music.

I'm back! Listening to Prestige the book -- a history of Prestige Records -- is in production, and will be published this winter by SUNY Press. So I'm back to the blog again, and will continue my mission to listen to, and respond to, every Prestige session.