LISTEN TO ONE: Scoochie

Booker Ervin had been in the studio for Prestige earlier in 1963, for a session with Larry Young, that was inexplicably shelved, not to see the light of day until many years later, in the CD reissue era, when it was coupled with an Ervin-Pony Poindexter recording which was made later in the year. He had appeared on one previous New Jazz recording, with Eric Dolphy and Mal Waldron. He was to become a mainstay of Prestige over the next few years.

Roy Haynes was already a Prestige mainstay, appearing with musicians covering the spectrum

from Willis Jackson to Phil Woods to Eric Dolphy. He'd played soul jazz with Shirley Scott, harp jazz with Dorothy Ashby, blues with Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and a little bit of everything with master of eclecticism Jaki Byard.

He had led his own trio (Phineas Newborn, Paul Chambers) in 1958, for a particularly beautiful album, We Three, and followed it in 1969 with another trio album (Richard Wyands, Eddie de Haas), Just Us. He had put together a couple of earlier sessions as leader with Mercury/EmArcy, and one with a smaller independent label. He told Ira Gitler that wanted to do more work as leader, because he could "set more of a pace," or as Gitler put it, he could "[pick] the tunes, the order they should be programmed in, and the tempo they should follow. The last, of course, is closest to the drummer's domain. Before he can do any of these things, a leader has to make his most important decisions--choosing the men who will play with him. Haynes has chosen well in the past, and his current quartet again reflects his good taste."

For his first Prestige album, Haynes had chosen two of the finest--and most talked about--of the younger musicians on the scene. For his second, he chose musicians who would never have the honors or name recognition of Phineas Newborn and Paul Chambers, but who were bold and sensitive, and delivered the music that Haynes was looking for. A 1962 session for Impulse! featured the rising star Roland Kirk.

Here, in Booker Ervin, he has another rising star, that would blaze forth through the rest of the 1960s on albums for Prestige and Blue Note, before Ervin's untimely death from kidney disease in 1970.

At 28, Ronnie Mathews was another young talent, and one who apparently appealed to the era's finest drummers--he had been discovered by Max Roach, and also worked extensively with Art Blakey. He had made his recording debut for Prestige in 1961 with Roland Alexander, and would lead a session of his own for the label later in 1963.

Larry Ridley was 26 when this record was made, and he had a fine career as a bassist ahead of, playing with Chet Baker, Kenny Burrell, Dexter Gordon and Stephane Grappelli among others, but perhaps an even more important contribution to the music was his work as an educator and administrator. He served as (and I'll just quote his Wikipedia entry here):

chairman of the Jazz Panel of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and was the

organization's National Coordinator of the "Jazz Artists in Schools" Program for five years (1978–1982). Ridley is a recipient of the MidAtlantic Arts Foundation's "Living Legacy Jazz Award", a 1998 inductee the International Association for Jazz Education Hall of Fame (IAJE), an inductee of the Downbeat Magazine Jazz Education Hall of Fame, a recipient of the Benny Golson Jazz Award from Howard University, and was honored by a Juneteenth 2006 Proclamation Award from the New York City Council. Ridley is currently the Executive Director of the African American Jazz Caucus, Inc., an affiliate of IAJE. He is also the IAJE Northeast Regional Coordinator. He continues to actively teach as Professor of Jazz Bass at the Manhattan School of Music. Ridley is currently serving as Jazz Artist in Residence at the Harlem based New York Public Library/Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. He established an annual series there dedicated to presenting the compositions of jazz masters that are performed by Ridley and his Jazz Legacy Ensemble.

Haynes also utilized the composing talents of the musicians he brought in. Ronnie Mathews composed "Dorian" and "Honeydew." Booker Ervin contributed "Scoochie," and Haynes finished the session with his own "Bad News Blues." Randy Weston is represented by his tribute to Melba Liston, "Sketch of Melba."

They play one semi-standard, "Under Paris Skies," originally composed by Hubert Giraud for the French film Sous le Ciel de Paris, later recorded by Edith Piaf. With English lyrics, it became a favorite of vocalists and mostly of sweet-music dance bands, although it has had some jazz adherents, most prominently Duke Ellington. Art Van Damme and Quincy Jones both also recorded it. Haynes liked the tune, and featured it in his club performances, often with Frank Strozier soloing on flute. Haynes's virtuoso lead-ins are a strong feature of all the tracks on this album, but on this one he really goes to town, driving all thoughts of sweet strings out of your head. Larry Ridley joins him on bass before--over thirty seconds in--Ervin enters, playing the familiar melody, and sticking mostly close to the melody for a full three minutes, as Haynes continues to kick it hard. The real improvisation starts with Mathews, and continues with Ervin, until the head is briefly restated at the end, this time by Mathews, perhaps somewhat sardonically.

"Bad News Blues" is a first rate example of what sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder used to call a "five-o-clock blues" -- it's the end of a session, we've played all the tunes we came in with, let's just play some blues. Prestige founder and president Bob Weinstock loved a good jam session, and a lot of good ones came out of this approach, with "Bad News Blues" being a prime example, Haynes setting the pace and everyone getting some room to blow.

Mathews's "Dorian" is in the Dorian mode, the minor-key modal structure made most famous by Miles Davis's "So What" and here turned into a moody, emotionally stirring piece, particularly in Mathews's own solo. All of this is taken at a quick tempo, not what you'd think of as the first choice for moody introspection, but it works. "Honeydew" is altogether different, with Ridley playing the blues right out of the gate, with Mathews and Ervin joining to create a full-bore, major scale excursion into rhythm and blues with Haynes providing a complex but driving alternative to the back beat.

"Scoochie" is Ervin's, and it is not only scoochie, it is downright scorchy. Ervin had introduced the tune a few years earlier in the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art, in a group led by Teddy Charles and also featuring Booker Little. If that rendition scooched the statues into life, this one would have scorched and singed them, with Haynes providing the beat, Ervin flying high, and Mathews turning in a piano solo that echoes and extends what Teddy Charles did in the Garden.

Haynes had entered a phase of his career where he wanted to work more as a leader, with his own groups, but he was only to make one more record for Prestige, and then one for Pacific Jazz, and nothing else in the 1960s, though the 1970s were a much more fruitful decade for him in the leader role, and he was to continue as a jazz stalwart, and a jazz legend, into his 90s.

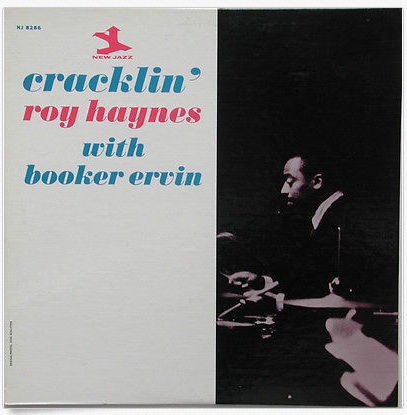

Cracklin' was the title of the New Jazz album release,and the title credit was Roy Haynes with Booker Ervin. The two Mathews compositions, "Dorian" and "Honeydew," were a 45 RPM single. Ozzie Cadena produced.

1 comment:

One of the baddest dates, ever!!

Thanx

Post a Comment