LISTEN TO ONE: I Feel All Right

Shirley Scott returns with a new soul collaborator and a new soulmate—her new husband, Stanley Turrentine. Turrentine was signed to Blue Note, but the two labels were friendly rivals—Blue Note’s Alfred Lion had given Bob Weinstock the push that moved him to start Prestige and get into the jazz recording business. So the two labels worked out a deal whereby the happy couple would record for both of them—Shirley as nominal leader for the Prestige sessions, Stanley for Blue Note. Both labels, of course, utilizing the genius of Rudy Van Gelder in the recording studio. Both continued to have separate careers, as well.

Married in 1960, they began collaborating in 1961, at a point where they had worked out their marital contracts, but not, apparently, their recording contracts to everyone's complete satisfaction. On their first session together, for Blue Note in June, she is listed as Little Miss Cott, with a knowing wink in the liner notes (Stanley and Little Miss Cott "really have something going. It is akin to a musical love affair") and even more knowing wink with the album's title and its title cut (Dearly Beloved). By November, when they made their first recording for Prestige, he was still listed in the session log with a pseudonym (Stan Turner) but by the time the album was released in 1962, an arrangement had been struck, and Turrentine is credited under his real name, with acknowledgment that he appears courtesy of Blue Note Records.

This session was recorded on January 10. Just over a week later, on January 18, the two of them were back in Englewood Cliffs to record for Blue Note (a short session, with two of the four tracks rejected), and in February they were back again for Blue Note.

Major Holley, who had been aboard for an early January Turrentine session with Kenny Burrell, for

Blue Note, played on the Prestige session, sat out the January 18 Blue Note session, and was back again for the February session. Scott liked to work with a bass player, which was not the case with all jazz organists--many of them preferred to take care of the bass line themselves. In fact, during this period, when the organ was becoming really popular as a jazz instrument, many bandleaders preferred to hire an organist as their keyboard player. With the bass part taken care of, it meant one less musician's salary to deal with. Holley was a recent addition to the Prestige stable, having recorded four albums with Coleman Hawkins.

The drummer on this and one more Scott-Turrentine session, but not on the Blue Note sessions, was Grassella Oliphant, a newcomer to Prestige and a new name to me--in fact, I thought at first that Scott had hired a woman drummer, but the first name was misleading. He was generally known by friends and associates as Grass, and that played nicely into the two albums he made for Atlantic as a leader, The Grass Roots and The Grass is Greener. Oliphant was a veteran by the time he hooked up with Scott and Turrentine. He had worked with Ahmad Jamal in 1952, and later with Sarah Vaughan. Vaughan praised him for his nice and easy touch with the brushes, and one imagines he probably was valued by Jamal for much the same reasons. One would not immediately seize on someone with those credentials as a soul jazz drummer, but Oliphant's contributions on this album, particularly his work on the ride cymbal, are exactly what's needed.

Oliphant worked through the 1960s and then basically retired from the jazz world to raise a family. The retirement stretched to nearly 40 years, but he picked up his career again in the new millennium, and was active until his death in 2017.

The most important name in this quartet, of course, is Stanley Turrentine. The Scott- Turrentine marriage lasted ten years, so it must have had some harmony to it, but their musical partnership was definitely harmonious. Scott was one of the pioneers of the soul jazz organ, and, with Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, one of the pioneers of the organ-tenor sax combo, and as soul jazz became a more and more dominant sound in the early and middle 1960s, her partnership with Turrentine kept her right in the thick of it.

Stanley Turrentine began his career with Earl Bostic, and Bostic's bluesy lyricism was definitely an influence, but he was definitely a man of his time, with a full tenor sound and a soulful bent. All that can really be heard on "Secret Love," the movie ballad by Sammy Fain and Paul Francis Webster, popularized by Doris Day, a tune that Bostic might have recorded but didn't. Turrentine leads off with the head, full-toned and lyrical in the Bostic style, albeit a little more uptempo and with some kicking work by Oliphant. He then goes into an improvisation which keeps much of the same feeling, with some punctuation by Scott. When Scott enters, she brings what only Scott can.

I've always heard a different approach to the organ in Shirley Scott's work. The soul jazz organists, and the were an incredibly talented bunch, mostly played the organ as a keyboard instrument with special properties--which of course it was. But Scott seemed to me, more than the others, to be intrigued with finding out all the different things an organ could do. It made for an exciting blend with Davis's raunch, and it makes for an exciting blend with Turrentine's lyricism.

Much of this album is taken up with an unusual and interesting blend of standards, given the soul jazz treatment. You might not expect "Secret Love" to be all that soulful, but others have done it successfully, including a doo-wop version by the Moonglows, and Scott and Turrentine breathe soul into it. Going back a little further, they pluck a tune by Sy Oliver that was first recorded in 1941. Oliver had just been pirated from Jimmie Lunceford's orchestra by Tommy Dorsey, looking to add some serious swing to his ensemble, and in the 1941 version by Dorsey, with Oliver and Jo Stafford handling the vocals, you can hear the beginnings of soul, that would be developed in the 1950s by Della Reese, the Pilgrim Travelers, Ray Charles (especially!), Pat Boone, Kate Smith...what? OK, maybe not everyone who recorded it gave it soul. But Scott and Turrentine certainly do.

They go back to 1925 for an Irving Berlin favorite, "Remember," which was actually recorded by Earl Bostic in 1955, when Turrentine was in the band (he had replaced John Coltrane). Bostic's version gives him a chance to show his raunchy rhythm and blues side, and Turrentine and Scott take it from there.

They pay homage Wild Bill Davis, the pioneer of soul jazz organ and an early influence on Scott.

But they reach their soul summit on this album with two Turrentine originals, "The Soul is Willing" and "I Feel All Right." I wonder if they had originally been planning to make 45 RPM single releases out of the two recent chart hits, "Secret Love" and "Yes Indeed." Maybe they did, and maybe "The Soul is Willing" and "I Feel All Right" were just so damn soulful that nothing else would do. Anyway those were the two 45s, and each of them two-sided, Parts 1 and 2, so nothing needed to be edited down.

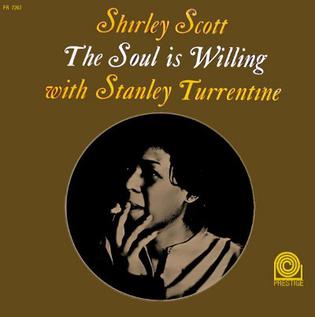

The Soul is Willing was the name of the album. Ozzie Cadena produced.

originators of the Philadelp

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-10343692-1542514814-3663.png.jpg)

1 comment:

I picked up a really cheap copy of this album with a really bizarre cover - looks like an amoeba's a-hole under a microscope - but what an album!

Post a Comment