LISTEN TO ONE: Doodlin'

And while Horace Silver, as a composer, may not have had the depth of a Monk or an Ellington, he certainly knew how to write some catchy tunes, and an album devoted to them, especially as played by Scott, is going to be great for listening, for finger snapping, for toe tapping.

And one wonders if there was a marketing consideration here. Both Prestige and Blue Note were going after the new and burgeoning soul jazz market, with Blue Note having the inside track, largely because of Horace Silver. Prestige wasn't going to get Silver, but they could get his name on an album cover.

One way or another, there can't be anything wrong with hearing tunes like "Doodlin'," "Senor Blues" and "The Preacher" played by someone as inventive as Scott, combining a popular touch with a gift for musical exploration.

Scott was joined on this day by Otis "Candy" Finch, a drummer who worked with Scott, with her husband Stanley Turrentine, with Herbie Hancock and Dizzy Gillespie and others, before leaving New York for Seattle, where would teach and play music away from the limelight.

Bassist Henry Grimes, in his only appearance on Prestige. Grimes was shortly to launch into a career as one of the favored bassists of the avant garde, working with Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, Cecil Taylor and Pharaoh Saunders. But in 1961, he had already established himself a significant, figure, first in rhythm and blues (playing with Willis “Gator Tail” Jackson, Arnett Cobb, “Bullmoose” Jackson, Little Willie John and others), and then with a variety of mainstream jazz artists. His reputation as one of the most versatile bassists around was cemented in one weekend--the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival, the one captured in the documentary Jazz on a Summer's Day. He appeared with Benny Goodman, Lee Konitz, Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Sonny Rollins, and Tony Scott.

Grimes would go on to bring a whole new level of creativity to the bass throughout the 1970s, and then suddenly disappear from the scene, so completely that he was presumed to be dead. Free jazz didn't necessarily translate into a living, even for someone as respected as Grimes, and after his bass was damaged on a West Coast trip (strapped to the roof his friend's car, it was baked by the sun through three days of driving through the desert), he had to sell the instrument.

He described what happened next in an interview with Jon Liebman of the For Bass Players Only website:

HG: I worked as a janitor and maintenance man and day laborer. I also spent many hours in the library, studying literature and writing poetry, short stories and metaphysical ideas. I have around ninety notebooks at home with my writings from those times. I still continue to write today.

He lived like this for 35 years, until a social worker and jazz enthusiast named Marshall Marotte tracked him down. A younger jazz bassist, William Parker (also a free jazz player and also a poet) donated a bass to him, and he was able to resume his career.

FBPO: Did you ever really give up on music, or did you believe, deep down, that one day you would be back?HG: I never gave up on music, not for a minute. You could say I was absent for a long time, but I always believed I would be back one day. I just couldn’t see the way to get there, but I knew it would happen.

In the same interview, Grimes gave the best, perhaps the only reasonable answer to the question, "What would you be doing if you weren't a bass player?

This question doesn’t have any meaning to me. I am a bass player and violin player and poet. If I weren’t those things, I wouldn’t be Henry Grimes. I wouldn’t be… at all.

Grimes married, continued to create and teach and write, and lived a fulfilled life until finally felled in April of this year by the Covid virus.

Scott's second session of the day marked the start of a new association, both musical and personal. She had certainly been one of the most important figures in establishing the soul jazz organ/saxophone sound through her work with Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis; now she was to continue to mine that vein with a new saxophonist, Stanley Turrentine, who was also her new husband. Turrentine was signed to Blue Note, so as the two continued to record together throughout the 1960s, they would be billed under her name for Prestige albums, under his for Blue Note sessions. I'll have more to say about him, and their partnership, in chronicling subsequent sessions.

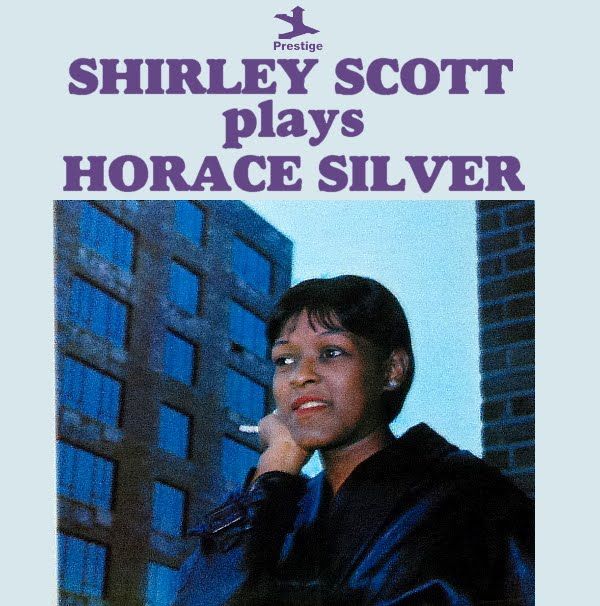

Esmond Edwards produced. The trio album was called Shirley Scott Plays Horace Silver, the quartet album with Turrentine Hip Twist. Both were released on Prestige. There were 45 RPM singles released from both sessions: "Sister Sadie, parts 1 and 2," and "Hip Twist, parts 1 and 2."

No comments:

Post a Comment