How about someone who's been doing it since the 1930s?

This is a sound that goes back in time, and back in place, all the way to Texas. Nick Morrison of Tacoma, WA station KNKX (jazz, blues and NPR news) described it nicely: “a sound which is very robust, sometimes raw, and which mixes the musical vocabularies of swing, bebop, blues and R&B.”

The Texas tenor sound embedded itself indelibly into the jazz fan’s consciousness on May 26, 1942, in a New York City recording studio, when a 19-year-old Louisiana-born, Houston-bred musician named Illinois Jacquet stepped up in front of the Lionel Hampton orchestra to play one of the most famous jazz solos ever recorded, on what may well be the perfect single record, “Flying Home.”

Arnett Cobb would replace Jacquet in Hampton’s band later in 1942, and gain renown for his own solos on what would become Hampton’s theme, “Flying Home #2.”

Cobb got his start in Texas playing with local bands and then with one, Milt Larkin, that toured beyond the Southwest, and showcased bandmates Cobb and Jacquet for greater things.

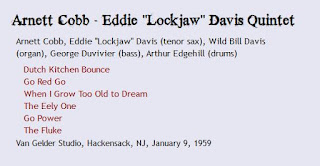

Cobb went on to lead his own band in the 1940s, but the 1950s were a tough decade for him. Spinal surgery in 1950 set him back, and when he recovered, he was shortly to be involved in a serious auto accident, after which the Wild Man of the Tenor Sax could only walk with crutches, and could only play propped up on a crutch. When Bob Weinstock signed him to Prestige in 1959, he had not led a recording date since 1947.

But he was the right man, in the right place, in the right time. The new gospel-tinged sound of soul jazz, as pioneered by the likes of Ray Charles and Horace Silver, may have been news to white northern critics, but it was mother’s milk to an old Texas tenorman like Arnett Cobb. And that innovative new organ-tenor combination that was being introduced to jazz audiences by Shirley Scott and Eddie Davis? Cobb and Wild Bill Davis could handle it. They’d first played it together back in the 1930s, with Milt Larkin.

It’s interesting to listen to the difference. With Scott and Davis you can hear that searching, that experimentation, that sense of creating something new. With Cobb and Davis, there’s that familiarity that allows for a different, no less exciting kind of exploration.

And of course, here it’s Cobb, Davis and Davis.

The group takes on a series of originals, including some, like “The Eely One,” “Go Red Go” and

“Dutch Kitchen Bounce” that are long time features of Cobb’s repertoire, and a Sigmund Romberg standard, “When I Grow Too Old to Dream.” We know from listening to Davis and Gene Ammons that the gutbucket blues stars of the tenor saxophone often have a softer side, and a sensitive way with a romantic ballad, and this is true of Cobb too...to an extent. Cobb is from Texas, and as Nick Morrison describes it, “Cobb's solos are textbook examples of how to play Texas Tenor blues [or in this case, ballads]: cool and smooth at the beginning, but sassy and feisty at the end.

This was ballad enough, and feisty enough, for Weinstock to release it as the 45 from the session, with “Dutch Kitchen Bounce” on the flip side.

Guys who work at night making sublime art are often likely to want to relax the next day with cartoons, and perhaps that’s what George Duvivier had been doing when he penned the composition he was bringing to the session. Perhaps he’d been listening to one of the commercials that went with those kiddie shows:

He’s got go power, there he goes!

Whooosh! He’s feeling his Cheerios.

These guys were feeling their Cheerios—or something—when they recorded this. It doesn’t let up for a second. It’s soul jazz, Texas style, and it’s a thrill ride. They don't let up, and they don't ever stop improvising, either. If you think that all honking tenor riffs sound alike, think again. Illinois Jacquet may have kick-started the engine, but he and the other jazzmen who played in this style were always looking to take it farther, and faster, and wilder. Cobb and Davis spur each other here--and if you're not afraid of losing your seat on the express, take a moment to listen to what George Duvivier and Arthur Edgehill are doing to propel this juggernaut. Shirley Scott and Eddie Davis knew what they were doing when they tabbed them.

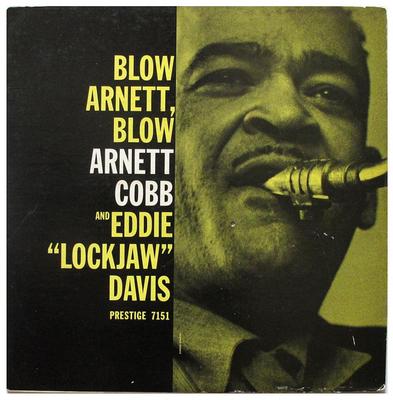

This album has Go Power, and it would be rereleased as Go Power, but the original release is Blow, Arnett, Blow. And good on Bob Weinstock, who was adding Arnett Cobb, who'd been more or less forgotten by 1959, to one of the hot new stars of his label, but gave Cobb the lead billing.

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 2

Listening to Prestige Vol. 2, 1954-1956 is here! You can order your signed copy or copies through the link above.

Tad Richards will strike a nerve

with all of us who were privileged to have lived thru the beginnings of

bebop, and with those who have since fallen under the spell of this

American phenomenon…a one-of-a-kind reference book, that will surely

take its place in the history of this music.

--Dave Grusin

An important reference book of

all the Prestige recordings during the time period. Furthermore, Each

song chosen is a brilliant representation of the artist which leaves the

listener free to explore further. The stories behind the making of each

track are incredibly informative and give a glimpse deeper into the

artists at work.

--Murali Coryell

No comments:

Post a Comment