His brother had a bar called maceros. ..Teo used to have his acts try out new material there...I saw max roach w/ Abby Lincoln, etc.

Like Miles Davis, Macero would be moving on to Columbia, for whom he had recorded one album in 1956. This Prestige session was only a blip on the radar screen, because later in 1957 he would return to Colubia, where he would make his greatest reputation as a producer of some of jazz's most highly regarded albums, including most of Miles's Columbia output, most notably Kind of Blue. He also produced Dave Brubeck's Time Out, Monk's Dream, and Mingus Ah Um. Mingus thanked him, in the liner notes to his orchestral work Let My Children Hear Music, for "his untiring efforts in producing the best album I have ever made."

If this was a golden age of jazz, not just a golden age of Prestige Records--and it was--Teo Macero had a lot to do with it. Because it was also a golden age of recording. They didn't have the equpment available today. Rudy Van Gelder created magic in his parents' living room. Les Paul and Buddy Holly and others created new and innovative recording techniques using home equipment. Patti Page, even before the widespread use of tape, managed to overdub herself and create five-part close harmony using acetate. Gil Melle invented a number of electronic instruments. Bo Diddley created guitars that looked like no guitars anyone had ever seen,

Nowadays, pretty much anyone can do pretty much all of this. It's like what I used to tell my screenwriting students after showing them Vittorio DeSica's Bicycle Thief: "Any one of you could do this. It wouldn't take much of a budget. You could use amateur actors the way he did. You could take a hand held camera out into the streets of Poughkeepsie. All you'd need would be genius."

Van Gelder and Paul and Holly and Page and Melle and Diddley had vision. So did Teo Macero, and in a 1997 interview with Iara Lee he talked about it:

In the '50's and '60's we didn't have anything lik=e a digital delay. We had to manufacture a digital delay. Now when you want a digital delay, you turn your machine half a step or whatever it is. To me, that doesn't really make the difference. It was the crudeness of all the things that we did.Q. You were talking about the crudeness being important.A. Yeah, it was a very inventive period in the '50's and '60's and the late '40's…many times we used a lot of electronic effects on Miles which Miles really didn't have anything to do with except in the final analysis, whether he liked it or disliked it.I think that the effects that we created in those days were much more real. Everything today, with electronics is synthetic. You turn a button here, you get it a half step higher, turn a button there you get it half a step lower, or you stretch it out. But they're not doing it correctly. I don't think they're doing it the right way- there are no highs and no lows. There's just a bunch of noises. We always had direction. When we were doing it, there was always a pivot point and then you moved on from that and then created these sounds. And that brought them back to simplicity again. Now everybody gets out there and they want to play that stuff ,I do it myself, but after fifteen minutes your mind starts to wander and the players start to wander and there's no definition. I mean music has to have lines, has to have dynamics, has to have emotion, all the elements that make it in music. But today, with the synthetic stuff, you got a gimmick here and a gimmick there, that's still not going to make it.In the old times, we would take two tapes, put them together on two different machines, record on the third one and try to sort of sync them up. But not sync them up exactly, it's just a fraction off, so that you wonder when you listen back to some of the Miles things, for instance, you wonder how this sound was created. Now, I did all that in the studio.

Times change, and tastes change, but there's always something about imperfection that's wonderful, especially as perfection becomes easier. Robert Herrick knew it in the 17th century, when there wasn't a lot of technological perfection:

Delight in Disorder

A sweet disorder in the dress

Kindles in clothes a wantonness;

A lawn about the shoulders thrown

Into a fine distraction;

An erring lace, which here and there

Enthrals the crimson stomacher;

A cuff neglectful, and thereby

Ribands to flow confusedly;

A winning wave, deserving note,

In the tempestuous petticoat;

A careless shoe-string, in whose tie

I see a wild civility:

Do more bewitch me, than when art

Is too precise in every part.

And there will always be some who like the other extreme. Disco producer Nile Rodgers was doing a session once with a series of electronic drum tracks, and an engineer finally decided he'd had enough perfection. He programmed a tiny glitch, way down in the mix. When Rodgers heard the playback, it was like the response of the princess to the pea: "If I wanted mistakes," he said, "I'd have hired a real drummer."

Teo Macero sought perfection, but he worked hard for it. From the same interview:

Macero put his heart into it. It would have horrified Bob Weinstock, but it was real to him in a way that the technology of a later generation could never be. I wrote about this when I was doing the Miles Davis Contractual Marathon sessions:if I needed something in a hurry, I'd get some loop machines which created a lot of illusions for Miles. They were made, one of them is in here. I got another one in the studio. But they were all sort of electronic pieces that were made that I finally bought from CBS because I thought they were so great. I mean you can't duplicate this today because they have movable heads on it. That was very crude. I mean today you turn a button and you might get the digital delay on one track and not on the other. But we had a lot of fun experimenting...when you cut and you edit you can do it in such a way that no one will ever know. And those days we still were doing it with a razor blade. I mean it's not like digital recording now where you got the 24 tracks and all kinds of equipment. You can put it on the computer. You can do all the things you want to do. If you want to move that thing over, I mean not one beat but maybe a beat and a half or beat and a 1/6. So you create a wash. There's a lot of things that you can do today that we didn't have the techniques to do in the late '50's and early '60's. But I think In A Silent Way is really a remarkable record for what it is. I mean for a little bit of music it's turned into a classic. And we did that with a lot of other records of his where we would use bits and pieces of cassettes that he would send me and say, "Put this in that new album we're working on." I would really shudder. I'd say, "Look, where the hell is it going to go? I don't know". He says, "Oh, you know".... I have a device called "the switcher", and it takes this program and moves it. We have one record out there with that. I put it on the drums, it sounds like the drummer has got 8 hands and 8 feet. It goes (imitates sound) and it all was done on one track. So I said, you know, the drums come out the center and Miles out the left and something out the right, to me it wasn't the way to do it.So the way I did it, I got Miles in the center. I put this drum track on this fancy switcher so it created the stereo versions. And then I had the bass and the sax. It's an interesting concept. In fact, we used it just recently on a couple of albums and it works beautifully. I mean those were the kind of electronic things sort of hand-made. They're not very fancy but they do what you cannot do with the synthesizers and electronics at the moment...Q. Contemporary digital equipment doesn't create funky music anymore?A. Contemporary music, electronically... no. Because what happens is it's too beat-oriented, it's locked in, there's no emotion. We never did that. We always played very loose, but we had a direction to go to.

There's always a pendulum in any aesthetic. Some small independent jazz labels of the 21st century,The first Columbia album, Round About Midnight, came out in 1957, and was not all that well reviewed. Critics found it wanting in comparison to the Prestige albums, though this judgment was to change over time, and Round About Midnight would become a classic...what really interests me here is the possibility that the passing of time may have led to a changing of tastes.... "Two Bass Hit" took six takes, and the finished version splices the beginning of take two to the end of take five. Artists (including Miles) would come to take it for granted that if they missed a high note, they could come back into the studio and hit just that one note, and have it spliced in.Today some critics, perhaps many of them born and raised in the in the era of studio perfection, are a little snarky in assessing the Prestige catalog. Ragged, they say. Bob Weinstock preferred quantity to quality, rushed his sessions, didn't allow his musicians to rehearse, never did more than a couple of takes. But maybe back then, that ragged edge was more appealing, more authentic. Maybe the critics of 1957 were put off a little by the studio-perfected sound.

like Mark Feldman's Reservoir Records, went back to two-track recording on the theory that you didn't need anything more to get the true feeling of jazz. And there's a reason why I chose to give my heart and soul to the Prestige recordings of the 50s rather than Columbia Records in the last quarter of the 20th Centtury. But listening to Teo Macero talk about his work in the studio is listening to a man in love with what he was doing.

Macero in 1957 had been on the jazz scene for a while. He went straight from his 1953 Juilliard graduation to working with Charles Mingus, with whom he co-founded the Jazz Composers Workshop. He made several albums with Mingus, and one as leader on Mingus's Debut label. He was active as a composer, and in fact won a Guggenheim fellowship for composition in 1957, and another in 1958. His 1956 Columbia was made with Bob Prince, himself a composer, perhaps best known for his scores for Jerome Robbins ballets.

Both Prince and Macero were known for their experiments with Third Stream music, but there's not much Third Stream on this album, and for that matter, not much of Macero as composer. The selections are two Mal Waldron compositions, one from Teddy Charles, one standard ("Star Eyes," introduced in a forgotten 1943 movie, entered the jazz lexicon when Charlie Parker recorded it), and one tune ("Please Don't Go Now"), that I can't identify.

Macero and Charles were both noted for their avant garde tendencies, and they play off each other in exciting ways here. Mal Waldron is more known as a straight-ahead player and composer, but he rises to the occasion with the most unusual tune of this session, "Ghost Story," which is never anything but unexpected throughout its six and a half minutes, from its spooky opening to its tuneful head to Teddy Charles's progressively weirder solo, to Macero's moody and melodic solo which finds some unexpected directions of its own.

Macero's own composition, "Just Spring," is, by comparison, pretty mainstream.

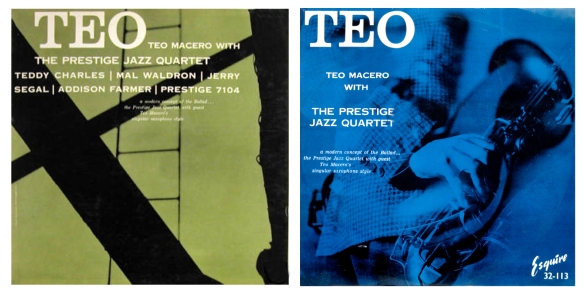

The session was produced by Teddy Charles, the first one to feature his Prestige Jazz Quartet by name, although they had worked one other session, the Prestige All Stars with Idrees Suleiman on April 14. The album was released as Teo.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

No comments:

Post a Comment