So this was a treat--three of the greatest improvisers in jazz, with a great rhythm section behind them.

Percy Heath, at this point, had no way of knowing that the group he had just recorded an album with would stay together for the next forty years and become one of the best known ensembles in modern music. Walter Bishop, Jr., was always a favorite of mine--I used to hear him at clubs in the 70s, if my memory for decades is still sharp. He seems to have always had music in his life--his father composed hits for Billie Holiday, Louis Jordan and Frank Sinatra, and his high school friends included Kenny Drew, Art Taylor and Sonny Rollins, with whom he's reunited on this album. With soloists like Parker, Davis and Rollins, one might think there would not be a lot of solo time left over, but Bishop gets his licks in, especially in "Compulsion," and he more than holds his own.

I think this is Philly Joe Jones's first recording with Miles, and he makes his presence felt immediately, with a drum roll to lead off "Compulsion." He sounds like a man who's come to stay. And it turns out that he was, even though the first classic quintet was not to come together for another three years. But in the interim, Davis and Jones found their own way of working (from Drummerworld)

The two would travel around the US stopping in cities to do a gig with the local talent. "Philly Joe Jones and I would go from city to city playing with local musicians. Philly would go ahead of me and get some guys together and then I would show and we’d play a gig. But most of the time this shit was getting on my nerves because the musicians didn’t know the arrangements and sometimes didn’t even know the tunes"(Miles’ Autobiography 179).Now, the main course. This is a classic Prestige blowing session, classic unrehearsed spontaneity, counting on the players to make it work, and they do. They are so attuned to each other. Bebop was built on the idea of the virtuoso soloist, for a number of reasons -- not the least of them, the wartime tax on establishments that had dancing, so a lot of small clubs found it necessary to hire virtuoso soloists whom the audience would want to sit and listen to. At any rate, amazing virtuosity was developed. And a common language was developed, so these guys -- three of them here -- could volley musical innovations back and forth -- a language better than spoken language, because they always know when to come in, and exactly what to say.

Still, you have to have somewhere to start. I'm guessing that "Compulsion" was a tune they all knew well, and had all played before, because they play the opening unison statement of the theme for a few choruses, and "The Serpent's Tooth" is a little newer to them, because their unison segment is a lot shorter. This theory falls apart when we get to "'Round Midnight," because everyone knows that, and there's no unison statement of the theme at all. Maybe they just figure they don't need to. It starts with Bird playing the chorus alone, and Miles finding his way around and into Bird's mood..

Here's what Ira Gitler had to say about the session:

"Compulsion" is a swinging Davis opus with two choruses apiece by Miles, Charlie and Sonny with the group riffing at intervals during Miles' and Charlie's choruses. Then Walter Bishop, a most flowing modern pianist, plays two more choruses before the theme is restated.

"The Serpent's Tooth" is presented in two takes. Take one is medium tempo and the solo order is Miles, Sonny and Charlie for two choruses apiece followed by Walter Bishop for one. Then Miles engages conversation with Philly Joe Jones. On take two the tempo moves up a bit. The solo order and their length is the same except that in the conversation with Philly Joe, Charlie and Sonny, in that order, jump in after Miles.

"'Round About Midnight" was 'round 6 p.m. when it was recorded on this particular day

and due to circumstances, new sadnesses were injected into Monk's already melancholy air. For various reasons the date had not jelled to expectations. The engineer, who hadn't helped much, went off duty and told us that the studio would close at 6, and that another engineer would take over for the last half hour.After a few unsuccessful attempts at "Well You Needn't," it was decided to close with "Midnight." This at a quarter to six. Miles and Charlie are the horns with the latter playing obligatos to the melody statement and crossing the bridges alone at both beginning and end. His opening solo is full of the pain and disappointment he knew too well and is an emotionally moving document as such. Miles cries some too.

I'm not sure that the circumstance of only having fifteen minutes to cut a tune is one that promotes sadness. Tension, yes. Pressure, yes. But maybe Gitler is right. No time to be clever, no time to intellectualize it. Just go with the emotions closest to the surface, and for Parker pain was never far below.

Not much more you can say.

Except that maybe having a brilliant virtuoso soloist isn't always enough to stop people from dancing. I was at Jazzfest in New Orleans one year, and Dave Brubeck was booked on one of the main stages, in between Ernie K-Doe and another rhythm and blues act. So a lot of the audience hung out there, and they were a crowd that had come to boogie. Brubeck was playing "Take Five" and other undanceable music, but this crowd didn't know you couldn't dance to it, and they were boogieing up a storm. I was close enough to see Brubeck's face, and he was loving it. He was having the time of his life.

And another thought. What happened to the big bands? Well, for one thing, they didn't go away completely. You still had the society bands like Lester Lanin and Meyer Davis. You still had the radio and Hollywood bands like Les Brown and Ray Anthony. But the music business pros had figured out that to get people dancing, you didn't need great soloists like Lester Young. You could hire a bunch of union musicians when you had a dance gig, pay them scale, give them charts, dress them up in tuxedos, and everyone was happy. And they'd play a waltz, and a couple of fox trots, and a cha-cha-cha, and a Lindy hop, and the bunny hop. Hard to imagine Pres playing the bunny hop.

Also, times change. People were ready for a different kind of music. We know that during the big band era, singers -- even singers like Sinatra -- were secondary. The bandleaders were the stars. But during the Petrillo strike, when the bands couldn't record but singers could, the vocalists became the stars.

And maybe it was part of the same shift. People wanted to listen to personalities, individual virtuosi, whether they were instrumental virtuosi like Parker and Davis and Rollins, or vocal virtuosi like Frank Sinatra and Jo Stafford. And people tend to like singers. That's why King Pleasure, and H-Bomb Ferguson, and later Mose Allison were the biggest sellers for Prestige.

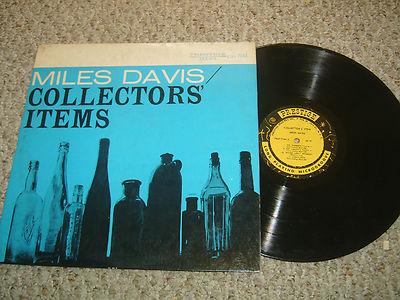

This session was released on a 7000-series, Collector's Items.

Several January 1953 sessions are unlocatable. Sam Most Sextet -- he's best known for an album with Herbie Mann. A Zoot Sims session with an organist -- very hard to find, much sought after by organ aficionados. Two recording sessions in Boston with Boston jazz legends Al Vega aand Charlie Mariano. Too bad. I would have liked to have heard all of them.

No comments:

Post a Comment