Thinking today about conservs' claim that Obama won because he handed out free stuff. Wouldn't it be great if that were true? Suppose instead of spending half a billion dollars on stupid campaign ads, a candidate would just say, "If I'm elected, I'll pay for the health insurance of everyone making under $200,000 a year for the next four years."

Tad Richards' odyssey through the catalog of Prestige Records:an unofficial and idiosyncratic history of jazz in the 50s and 60s. With occasional digressions.

Friday, December 06, 2013

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

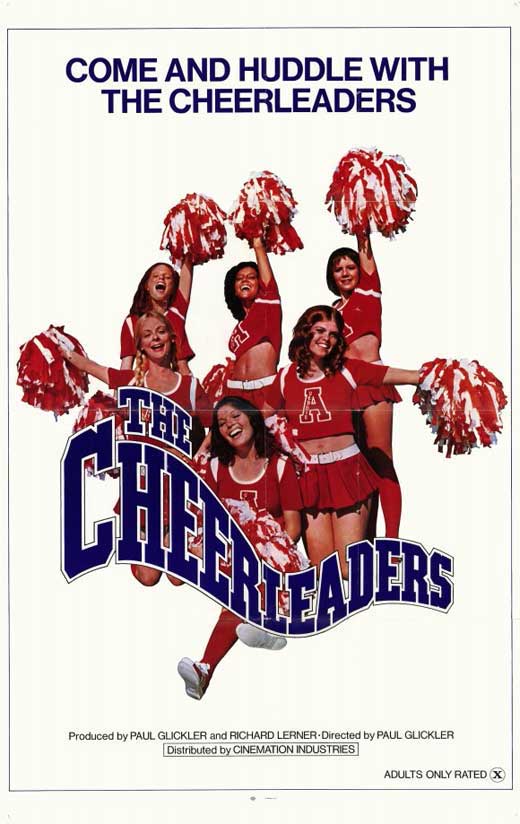

The Cheerleaders

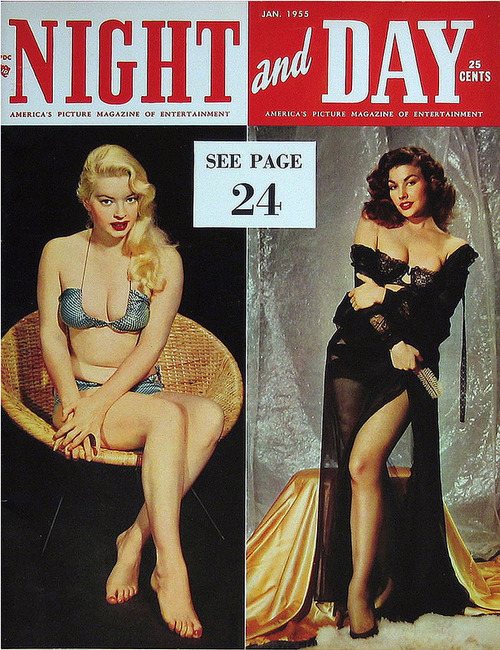

A little history, as best I remember it. In New York, in the 50s and early 60s, there were theaters on 42nd Street between 6th and 7th Avenues that showed skin flicks. These were mostly sunbathing and health movies, with lots of volleyball, but they also showed some amazing foreign films, like "Smiles of a Summer Night," because at the time, European films could show bare breasts but American films couldn't. (Some people will remember this. Here's something no one will remember except me, because at the time -- 1954 -- I was 14 and impressionable, and was occasionally able to get hold of magazines like "Night and Day" which featured pictures of Lili St. Cyr and Tempest Storm and the like. Anyway, one of them had a brief item that starlet Peggie Castle, in the new Western "The Yellow Tomahawk," with Rory Calhoun, would be wearing a flesh-colored bikini that would make her appear topless. I vowed to see "The Yellow Tomahawk," but it never came to our local theater.)

A little history, as best I remember it. In New York, in the 50s and early 60s, there were theaters on 42nd Street between 6th and 7th Avenues that showed skin flicks. These were mostly sunbathing and health movies, with lots of volleyball, but they also showed some amazing foreign films, like "Smiles of a Summer Night," because at the time, European films could show bare breasts but American films couldn't. (Some people will remember this. Here's something no one will remember except me, because at the time -- 1954 -- I was 14 and impressionable, and was occasionally able to get hold of magazines like "Night and Day" which featured pictures of Lili St. Cyr and Tempest Storm and the like. Anyway, one of them had a brief item that starlet Peggie Castle, in the new Western "The Yellow Tomahawk," with Rory Calhoun, would be wearing a flesh-colored bikini that would make her appear topless. I vowed to see "The Yellow Tomahawk," but it never came to our local theater.)

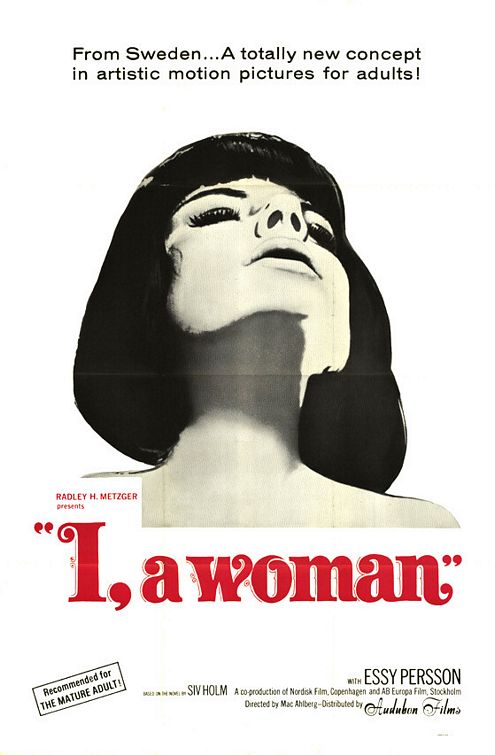

Back to 42nd Street -- not the well-known block between 7th and 8th, but its second banana to the east. Because some very good foreign films with nudity played the block, nudity came to be associated with dramatic seriousness -- that is, you could get away with it if you had some heavy drama. So the first real skin flick to hit America in a big way was the Swedish import "I, a Woman," in 1965, followed by "I am Curious (Yellow)" in 1967, which actually should have been banned in America for its open embrace of socialism rather than its open embraces (it and its sequel, "I am Curious (Blue)" were named after the colors of the welfare-state Swedish flag). The Swedish films were hugely successful at the box office, and of course hugely controversial.

By this time, Russ Meyer was making movies in America, including classics like "Faster, Pussycat, Kill, Kill," and things were opening up a little, but just a little. Meyer's films were not, at that time, widely distributed, certainly not in major theater chains. In 1969, an American film called "The Stewardesses" came out. I remember going to see it, although I remember absolutely nothing about it, except that I saw it with a group of friends. We were sitting

in the middle of the theater near the front, and at some point in the middle I had to go to the bathroom, which meant standing up and working my way past the row of moviegoers. I did so, clumsily, then turned and announced loudly, "I've never been so offended in my life. You told me we were going to see Mary Poppins!" and walked out.

in the middle of the theater near the front, and at some point in the middle I had to go to the bathroom, which meant standing up and working my way past the row of moviegoers. I did so, clumsily, then turned and announced loudly, "I've never been so offended in my life. You told me we were going to see Mary Poppins!" and walked out.But I digress. "The Stewardesses," to the best of my recollection, was a sort of "Where the Boys Are" with lots of skin, the sex-and-retribution theme so deeply entrenched in American Calvinist culture.

And at about that time, Paul Glickler, Richard Lerner and I had gotten financial backing to make a modest-budget skin flick, and responding to the box-office success of "The Stewardesses," we decided to call it "The Cheerleaders."

But we found we couldn't do the pseudo-heavy drama of "The Stewardesses," or even the somewhat better pseudo-heavy drama of "I, a Woman" or the not entirely pseudo-political message of "I am Curious (Yellow)." Our minds just didn't work that way. We ended up writing a flat-out comedy.

Which, it turned out, got us in trouble with our financial backers, who wanted the proven success formula of sex and melodrama (also, it was still believed that you could get away with more sex if your movie had "redeeming social value," which comedy clearly did not). So they ordered us, on pain of withdrawing financial support, to take out all the comedy and make it more like "I, a Woman."

Which we could not bring ourselves to do. But we had to sneak the comedy in, which meant taking out some of the funniest scenes in the original script. But we got a bunch of them in. One thing I

always liked about "The Cheerleaders" script -- usually in sex comedies, the setups -- seductions, seductions foiled, etc. -- are the comedy scenes. In "The Cheerleaders," we played the actual sex scenes for comedy, which I believe had not been done before.

always liked about "The Cheerleaders" script -- usually in sex comedies, the setups -- seductions, seductions foiled, etc. -- are the comedy scenes. In "The Cheerleaders," we played the actual sex scenes for comedy, which I believe had not been done before.Anyway, our financial backers were horrified by the finished product -- until they saw the audience reaction. People loved it, and they loved it for the comedy. So they pulled back the movie, and retooled a whole new advertising campaign -- the comedy smash of the year! -- and released it as a double bill with Ralph Bakshi's animated movie of R. Crumb's "Fritz the Cat." "The Cheerleaders" was the hit movie that carried the double bill, and it opened to national release in a major theater chain, Red Carpet Theaters, following "Man of La Mancha."

And became a minor cult classic. Got some good reviews, with the exception of the Boston Phoenix. Their reviewer hated it so much that for the next several months, every other movie he hated got an "at least, it's not as bad as 'The Cheerleaders.'" It is even mentioned in a John Grisham novel.

And that's pretty much the whole story, except that in the late 70s, the great New York art film house, Bleecker Street Cinema, did a retrospective of classic skin flicks, including "I, a Woman," the "I am Curious" movies, and "The Cheerleaders." I went to see it, figuring rightly that it would be my only chance to see a movie of mine in an art film house. As I was walking in, a couple were walking out, and I overheard this snippet of conversation.

He: I really liked that movie.

She: Yeah, you would.

He: No, I mean I really liked the writing. I thought it was incredible well-written.

It was all I could do to keep from grabbing him and saying, "Honest? Honest to God?"

Saturday, September 28, 2013

You like me, I like you

Interesting article in today's NY Times about likeability as a desirable characteristic in fictional characters. Mohsin Hamid says

Zoe Heller says

But likeability is a quality inexperienced readers use as a shield or security blanket when they don't know quite what to say, or what to think about, something they're encountering for the first time, and not on their own turf -- a classroom is never the student's own turf.

I used to bring this up a lot in my intro to lit classes. It was fairly common that a student, in a paper or a class discussion, would dismiss a book, or try to get out from under dealing with it, by saying the characters weren't likeable enough, or that the theme of a poem wasn't upbeat enough. In one such class -- this would have been in the 90s -- I asked

"How many of you are Guns 'n Roses fans?"

A bunch of hands went up.

"And what's the theme of most of their songs?"

The answer I got, which was a good one: "Life sucks, so let's get fucked up."

I also used to say -- your obligation in approaching a piece of literature is to be as smart as you really are in the rest of your life. You don't have to be told that you can get emotional satisfaction out of Guns 'n Roses even though they have a negative attitude toward life. You don't have to be a student of Empson to recognize the ambiguity in conversations in your real life.

At this point I'd tell a student in the front row to ask me how I was doing.

Student (a little nervously): How are you doing?

Me (snarling): FINE!

So how was I doing? Did anyone believe I was really fine?

No one needs to tell us, in our lives, to have the kind of sensitivity to nuance that we're asked to bring to literature. But our lives are our home turf.

I’ll confess — I read fiction to fall in love. That’s what’s kept me hooked all these years. Often, that love was for a character: in a presexual-crush way for Fern in “Charlotte’s Web”; in a best-buddies way for the heroes of “Astérix & Obélix”; in a sighing, “I wish there were more of her in this book” way for Jessica in “Dune” or Arwen in “The Lord of the Rings.”In fiction, as in my nonreading life, someone didn’t necessarily have to be likable to be lovable. Was Anna Karenina likable? Maybe not. Did part of me fall in love with her when I cracked open a secondhand hardcover of Tolstoy’s novel, purchased in a bookshop in Princeton, N.J., the day before I headed home to Pakistan for a hot, slow summer? Absolutely.What about Humbert Humbert? A pedophile. A snob. A dangerous madman. The main character of Nabokov’s “Lolita” wasn’t very likable. But that voice. Ah. That voice had me at “fire of my loins.”

Zoe Heller says

When the novelist Claire Messud rebuked a reporter earlier this year, for asking if Messud would want to “be friends with” the protagonist of “The Woman Upstairs,” her latest book, I was among those who applauded. It’s always cheering to have someone stand up for the not-nice in literature. Messud’s citation of various mad, murderous or otherwise unpleasant literary characters who have managed, despite their moral handicaps, to enthrall readers, was apt and enjoyably furious.

I grew a little uneasy, though, when in subsequent Internet discussions a consensus seemed to emerge that caring at all about “likability” was an embarrassing solecism, committed only by low-rent writers and hopelessly naïve readers. This struck me — and strikes me still — as faux-highbrow nonsense.

But likeability is a quality inexperienced readers use as a shield or security blanket when they don't know quite what to say, or what to think about, something they're encountering for the first time, and not on their own turf -- a classroom is never the student's own turf.

I used to bring this up a lot in my intro to lit classes. It was fairly common that a student, in a paper or a class discussion, would dismiss a book, or try to get out from under dealing with it, by saying the characters weren't likeable enough, or that the theme of a poem wasn't upbeat enough. In one such class -- this would have been in the 90s -- I asked

"How many of you are Guns 'n Roses fans?"

A bunch of hands went up.

"And what's the theme of most of their songs?"

The answer I got, which was a good one: "Life sucks, so let's get fucked up."

I also used to say -- your obligation in approaching a piece of literature is to be as smart as you really are in the rest of your life. You don't have to be told that you can get emotional satisfaction out of Guns 'n Roses even though they have a negative attitude toward life. You don't have to be a student of Empson to recognize the ambiguity in conversations in your real life.

At this point I'd tell a student in the front row to ask me how I was doing.

Student (a little nervously): How are you doing?

Me (snarling): FINE!

So how was I doing? Did anyone believe I was really fine?

No one needs to tell us, in our lives, to have the kind of sensitivity to nuance that we're asked to bring to literature. But our lives are our home turf.

Saturday, September 07, 2013

A Great Blog for Local History

Check out D.J. Boggs' new blog of memories of High Woods and Wilgus's General Store, owned and operated by her grandfather, the legendary Henry Wilgus.

Sunday, August 18, 2013

Historical Fiction and the real world

Very nice blog post by Michael K. Reynolds on the ways that

one can interface fiction and history. He offers three possibilities – The Rosencrantz

and Guildenstern Strategy (“if your lead character is Winston Churchill in the

early 1940’s, you are going to have a difficult time with it not being

swallowed up by World War II themes. However; if you shift your lead character to a young man from India who happened

to immigrate to England at the onset of the war, then this can take on a much

different path”), The Monet Approach (“the idea that blurred detailing can

actually provide a powerful and succinct image”), and The Character Pigeon (“use

a minor character (or characters) to carry the weight of the prevalent, but

non-centric theme. That way you’re not ignoring it, but you’re freeing your

lead characters to swim in the main waters of your story”).

It started me thinking about some of the ways I’ve dealt

with history in my own work. In my most recent, Nick and Jake, the era – and the

specific year, 1953 – are central to the story. Bringing Nick Carraway and Jake

Barnes into 1953 was important in that it gave a new perspective on the seminal

characters of a key period in American literature, but it was also important in

that it gave a new perspective on that year.

But for all that history was important, we still had to play

fast and loose with a few odd details. The overthrow of Mohammed Mossadegh in

Iran, which was the first CIA exercise in overthrowing the government of

another country, changed the history of

the Middle East irrevocably, and not the way the CIA expected it to.

We wrote Nick and Jake partly in response to the Bush

administration’s post-9/11 foreign policy, resulted in America having and then

losing the sympathy and support of international opinion. We were struck by how

much this mirrored the 1950s, when America went from being the country that had

saved the world from the Nazis, to being The Ugly American. The thing that made

the Iran coup so devastatingly successful was that no one believed the

Americans would ever do such a thing. So it was a perfect metaphor for us.

But it had happened in the fall of 1953, and the action of

Nick and Jake is in the spring of 1953. But it was too good for our plot to

leave out…so we moved it up a few months.

Our ingénue moves to

New York from the Midwest and undergoes some significant changes. Where would

she stay in the big city, a young, innocent girl? Why, the Martha Washington

Hotel for Women. And nothing says Martha Washington Hotel for women in the 50s

like Valley of the Dolls. Only trouble is, no one really remembers, or cares

about, the characters in Valley of the Dolls any more. Not that that would have

bothered us so much, except that we didn’t remember or care about the

characters either. Jacqueline Susann, the novel’s author, interested us as a

colorful character and a symbol of a certain literary/political zeitgeist. Only

trouble there was, unlike her characters, Jackie Susann was over fifty,

married, and living a totally different life from that of her characters. This

might have bothered us more than it did, if we hadn’t discovered it only after

we had begun writing her into the book. By the time we knew that she wasn’t

really one of her characters, we liked her too much to let her go. So we shaved

thirty years off her age – historically inaccurate, but that’s really the time

and place she’s associated with.

Here’s a character we pulled from history out of necessity.

When we went to do the audio dramatization of Nick and Jake, we were fortunate

enough to have Valerie Plame Wilson offer to play a role, but there was no role

for her. Who was important in the politics and cultural politics of 1953? Clare

Boothe Luce! She was perfect for the story, and perfect for Valerie – and of

course, since Valerie was playing her, we twisted history a little and made her

an undercover CIA agent. And who’s to say she wasn’t?

More on history, and other historical novels, next time.

Friday, August 16, 2013

Artists Studio Tour

Saugerties Artists Studio Tour was this past weekend. I opened my studio for two days -- actually opening my studio only involves lifting the lid up on my laptop, so I compensate by turning the Barbara Fite Room of the House on the Quarry into a showroom.

Anyway, I met a nice bunch of people -- probably about a hundred visitors on each day, and a few sales. I don't really show my work in galleries very often, so the Art Tour is my main showcase.

Here are a few pieces from this year, representing the different styles of work that I do. "Lizard" is 21st century pointillism, done with mouse and Microsoft Paint, background in Photoshop.

"Bunkhouse Guitar" is my black and white faux-woodcut style, also with mouse and MS Paint, using the freeform shape too and the invert command.

"Nude with Flower" is iPad, ArtStudio and finger.

In a conversation during the tour, I found myself remembering when I lived in New York in the 70s, and I'd find myself late at night on the subway, starting to notice some simple stick figures that someone was drawing on the black empty spaces where posters had not yet been put up. I was blown away by how good they were, and I kept telling myself I was going to come down one night with a razor blade and cut one of them out, to keep for my own. But I never got around to it. That's why I don't have an original Keith Haring in my collection.

|

| Lizard |

|

| Bunkhouse Guitar |

|

| Nude with Flower |

Here are a few pieces from this year, representing the different styles of work that I do. "Lizard" is 21st century pointillism, done with mouse and Microsoft Paint, background in Photoshop.

"Bunkhouse Guitar" is my black and white faux-woodcut style, also with mouse and MS Paint, using the freeform shape too and the invert command.

"Nude with Flower" is iPad, ArtStudio and finger.

In a conversation during the tour, I found myself remembering when I lived in New York in the 70s, and I'd find myself late at night on the subway, starting to notice some simple stick figures that someone was drawing on the black empty spaces where posters had not yet been put up. I was blown away by how good they were, and I kept telling myself I was going to come down one night with a razor blade and cut one of them out, to keep for my own. But I never got around to it. That's why I don't have an original Keith Haring in my collection.

Friday, June 14, 2013

What our lives are really like

The Burgess Boys by Elizabeth Strout

The Burgess Boys by Elizabeth StroutMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

Elizabeth Strout is a first rate writer, and I should have liked this more than I did. She has a fine ability to zero in on the subtleties of what's wrong with people. But I don't know...I think that what's really wrong with people is that witches keep telling them they can be king if they'll only murder a bunch of people, or that they've killed their father and married their mother, or even that their balls have been shot off and their girlfriend is having it on with a bullfighter. Those ring a bell with all of us, right?

I kept wanting this book, and these people, to mean more to me.

View all my reviews

Saturday, April 27, 2013

Brave, courageous and bold...

Doc by Mary Doria Russell

Doc by Mary Doria RussellMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

Got better and better as it went along. I ended up loving it. Probably about 85 percent real history, presented as a novel, but a sort of metafiction, with the author stepping beyond the fourth wall to talk to about the characters and their place in history,

I've written a novel -- Tempest of Tombstone -- about these characters -- the Earps, Kate Elder, Doc Holliday -- in Tombstone, and I did a lot of research for that -- nothing like the incredible research Russell has done -- but I knew very little about the Dodge City years.

Se gets so much right about the Old West, pointing out that a sheriff or deputy in Dodge City was essentially a small town policeman, breaking up fights between drunks, getting raccoons out from under buildings, answering calls to domestic disputes. Very little in the way of Gunsmoke - type gunplay. I also get so df NRA types - and anti-NRA types -- talking about the good (or bad, depending on your point of view) old days of Wyatt Earp and the Wild West where everyone carried guns and weren't afraid to use them. Wyatt Earp was the original gun control advocate, which is the reason why the Earps' reputations were destroyed by the gunfight at the OK Corral, even though they won it.

View all my reviews

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

Minutes of the Last Meeting

I used to give an assignment -- eavesdrop on conversations, and write down anything that you hear someone say in iambic pentameter. The purpose was to get poetry students away from the idea that metrical poetry has to be forced, or singsongy. I would tell them, at first this will seem impossible, but once you start hearing them, you'll hear them everywhere, and the real problem will become how to turn it off. Your girlfriend tells you, "I slept with your best friend the other night," and your response is, "That's great!" "It is?" "Yes, it's iambic pentameter!"

Anyway, one of the first times I gave this assignment, I decided to do it myself during a faculty meeting. I mean, you have to do something during a faculty meeting, don't you, to avoid going bonkers with boredom? So I started writing down lines, and pretty soon I had two pages of a notebook filled, and...I realized...a poem about academic life.

So here it is.

Anyway, one of the first times I gave this assignment, I decided to do it myself during a faculty meeting. I mean, you have to do something during a faculty meeting, don't you, to avoid going bonkers with boredom? So I started writing down lines, and pretty soon I had two pages of a notebook filled, and...I realized...a poem about academic life.

So here it is.

MINUTES

OF THE LAST MEETING

It

wouldn't interfere with what we do;

I

couldn't really poll the entire group.

Very,

very briefly, here's the plan--

Elect the

chairs of two committees first

(Able to

run for these positions first)

Who'll

want to lead the faculty towards greatness.

Within the

AAC or SAC,

At least

two people -- one is not enough –

The

faculty at large will vote for chairs,

The AAC,

I find, now having done it.

The AAC,

last Monday, voted no

—Selected by the faculty at

large—

And they

pick someone who they think can lead.

Maybe the

better thing would be to keep…

We have

to somehow pull it all together.

Did

everyone get a chance to sign the sheet?

There are

seven searches underway

From a

variety of different fields --

I know I’m getting questions all the time.

It’s not as academic a position,

The

college writing program and the core.

There is

the dean search, which is underway

A lot of

applications were dismissed

This

selection didn’t represent --

I don’t know anything about the search --

Is

uppermost in everybody’s mind --

And in

the end, of course, it’s Artine’s choice.

Monday, March 18, 2013

Ignore or Fight?

Back in the seventies, I was working in New York for a magazine, and in connection with an article, I had to go and talk to a guy named Alan Shackleton, who was a sleazy exploitation film producer.

At this time, there was a lot of press being given to rumors about a "snuff film" made in South America, a porn film that ended with an actual murder on camera. Shackleton, when I got to his office, was making plans to capitalize on the rumors. He had a cheap slasher movie, and he had quickly added a new ending to it involving a fake killing of the lead actress, or someone who he hoped looked enough like her, since the original movie had been shot several years earlier. When I walked in, they were all sort of in a panic. The film was so tame, in addition to being so lame, that the film review board was giving it an R rating. So they were scurrying around to find a piece of film from a porno movie that could be shoehorned in somewhere.

Apparently they succeeded, because the film opened a few days later with an X rating, the title of "Snuff," and the tagline "Filmed in South America...where life is cheap."

But meanwhile, when I got home that night, my girlfriend was making plans with a women's group to picket the theater when the movie opened.

"Oh, God, no," I said."Don't do that. Being picketed is this guy's only hope of making a profit on this movie. It's so awful no one will go to see it after the first day, but if the protest makes the TV news, that's box office gold for them."

But she and her group would not be dissuaded, and they did picket, and the film did make some money for Shackleton.

So I was right.

Maybe. You're really never wrong to stand up against the truly awful in society. I still think I was right...sometimes you're just playing into the bastards' hands. But maybe the bigger picture is it's not OK, and you always have to say it's not OK when it's not.

At this time, there was a lot of press being given to rumors about a "snuff film" made in South America, a porn film that ended with an actual murder on camera. Shackleton, when I got to his office, was making plans to capitalize on the rumors. He had a cheap slasher movie, and he had quickly added a new ending to it involving a fake killing of the lead actress, or someone who he hoped looked enough like her, since the original movie had been shot several years earlier. When I walked in, they were all sort of in a panic. The film was so tame, in addition to being so lame, that the film review board was giving it an R rating. So they were scurrying around to find a piece of film from a porno movie that could be shoehorned in somewhere.

Apparently they succeeded, because the film opened a few days later with an X rating, the title of "Snuff," and the tagline "Filmed in South America...where life is cheap."

But meanwhile, when I got home that night, my girlfriend was making plans with a women's group to picket the theater when the movie opened.

"Oh, God, no," I said."Don't do that. Being picketed is this guy's only hope of making a profit on this movie. It's so awful no one will go to see it after the first day, but if the protest makes the TV news, that's box office gold for them."

But she and her group would not be dissuaded, and they did picket, and the film did make some money for Shackleton.

So I was right.

Maybe. You're really never wrong to stand up against the truly awful in society. I still think I was right...sometimes you're just playing into the bastards' hands. But maybe the bigger picture is it's not OK, and you always have to say it's not OK when it's not.

Monday, March 11, 2013

How a poem comes together (sometimes)

I just found these old notes on my hard drive while looking for something else. They must have been something I started doing for a class at some time. I seem to have been following the genesis and development of a particularly slippery poem. The notes were apparently originally handwritten, and then transcribed over. I have no idea how much time went by between one and the next. I'm guessing that the lines of poetry and the metrical notations were the handwritten notes, and the exigeses came when I typed them all up.

FIRST PAGE OF NOTES

I was thinking of writing a ghazal,

and since I’ve been thinking a lot about a possible connection between ghazal and blues, I began

with

the blues

and then tried to fit a couple of

lines to it

The

first crack of light in the morning was the blues

When

all shadows were shadow, that was the blues

and at the same time, I written a

phrase I liked the sound of

striped

like snakes

and I started thinking of light –

morning light, maybe morning light across a bed, striped like a snake, and the

next line I tried was this:

She

woke up in the morning with her arms around the blues

The

morning light lay like a striped

SECOND PAGE

that seems to be as far as I got

with that thought. I was in the process of deciding I didn’t want to use

“blues” as the monorhyme end word in a ghazal. The next couplet I tried was

(brackets around works that were crossed out):

Morning

[began] started like a [striped] snake across her bed;

When

all shadows were shadow, the dark was her bed.

So I’d gotten rid of two things I

really thought I wanted to work with, the blues and “striped snake.”

The next thing I was going to get

rid of was the ghazal. It wasn’t working for me; I didn’t feel it. But I still

liked the formal regularity of the line, and I knew that the lines and rhythms

I was hearing were formal. I decided to try a villanelle.

Day slipped like a snake across her bed.

When the shadows clustered into shadow

She pulled the darkness up around her head.

Then, on the back of the page, a

bunch of scattered notes. I was trying to find rhythms that I liked.

-

/ - /

- / -

/ - /

day slithered like a snake across her bed

/

- / -

/ - / -

/

Day

slipped like a snake across her bed.

/

- / -

/ - /

-

Shadows

clustered into shadow

and a bunch of possible rhyme words

for the B rhyme:

shadow

meadow

arrow

tallow

and under the list of rhyme words, another

line:

hair

like snakeskin stretched across her bed

which seems to mean I was moving

away from the snake-as-sunbeam image, and this is maybe an example of letting a

fine isolated verisimilitude go by. I

think snake-as-sunbeam may well be a pretty good image. But I was allowing

myself not to be locked into it, to look around for other possibilities.

So here’s what fills up the rest of

this page:

Like

a snake she’d let into her bed

which I guess I hated. I hate it

now, looking at it. The metric pattern forces the line to sound stilted and

awkward – “LIKE a SNAKE she’d LET inTO her BED” - which puts that horrible, ugly stress on TO.

So under it, I have a note for the stress I want:

/ -

into bed (DA – duh INto BED)

and under that, a line that fits the

meter:

Like

a snake she’d followed into bed

which I also liked better as a plot

line, but I seem to have abandoned it. I go on to try a couple of other lines,

using one of the “B” rhyme words. I didn’t have the whole lines, just this

much:

- /

- / pretended she was dead

/ -

/ - , made her skin like tallow

and then filling out the lines

(indicating words crossed out, words stuck in, and in the third line, a

stressed syllable that had to go in, but I didn’t have yet):

For

two days, she pretended she was dead,

felt

[made]

her arms ^ like clay, [her] breasts like

tallow,

Hair

[hung] like snakeskin / across her bed.

Then, on the back of the page, a

couple of lines that don’t seem to be going anywhere, and I think I knew they

weren’t going anywhere:

When

she was seventeen and newly wed,

What men were

/ - pierced her like an arrow

PAGE THREE

By now, I had the beginnings of a

poem:

The day slipped like a snake across her bed,

And when the shadows clustered into shadow,

She pulled the darkness up around her head.

They challenged her to prove she wasn’t dead.

She showed her arms like clay, her breasts like tallow,

Her skin shed like a snake’s across her bed.

And it was working pretty well.

Except I didn’t like it. I liked the image of breasts like tallow, but “arms

like clay” didn’t do much for me. It seemed to be just there for the meter, to

fill out the line. “They challenged her to prove she wasn’t dead” seemed like a

nice line. It was metrically regular. It said something interesting. Why didn’t

I like it?

Looking at it again now, I do kinda

like it, and I like the formal poem that’s starting to take shape. But at that

point – and I hope my instincts were right – I didn’t like it at all. I didn’t

like the form, and I really didn’t like the meter. I wanted to break free of

it...into free verse, as a matter of fact. I guess that’s why they call it free

verse.

PAGE FOUR

So I changed “wasn’t dead” to “was

alive,” and I broke it into two lines, to shake myself loose from the metric

regularity:

To show them she was

alive, she wriggled free from

her skin, like a snake, and now

her new breasts were soft, like tallow,

So I’d completely and finally abandoned

the snake-as-sunlight image. Too bad, maybe. Or OK, maybe. Anyway, I needed to

start stripping things down. I knew I liked the image of breasts like tallow to

suggest a new, moist, not-quite-formed body emerging from the shed outer layer

of skin. Here’s the next start:

To prove to all three of them she was

alive, she shrugged free from

her skin, like a snake, and when

she turned around, her new breasts

were soft, like tallow,

[and her hands]

[and] her hair was downy, and white like milkweed,

and she blinked in the light.

But she was fast, she had

pads of air under her feet.

[and] She could move in any direction,

she could spin and dance like a leaf.

I tried out the “three of them” to

see if they’d open up an interesting plot line, but they didn’t, so I let them

go. This was pretty much the last hand-written draft.

That's the end of the notes I have in this file. If there were more intermediate steps, I don't remember them. But here's the finished poem.

PROOF

They asked her to prove she was real,

so she shrugged out of

her skin like a snake, and when she

turned around, her new breasts

were soft, like tallow,

her hair was white like milkweed,

and she blinked in the light.

But she was sudden, she had

pads of air under her feet.

She could move in any direction.

She could flip and scoot like a leaf.

She turned into shadow with the shadows.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)