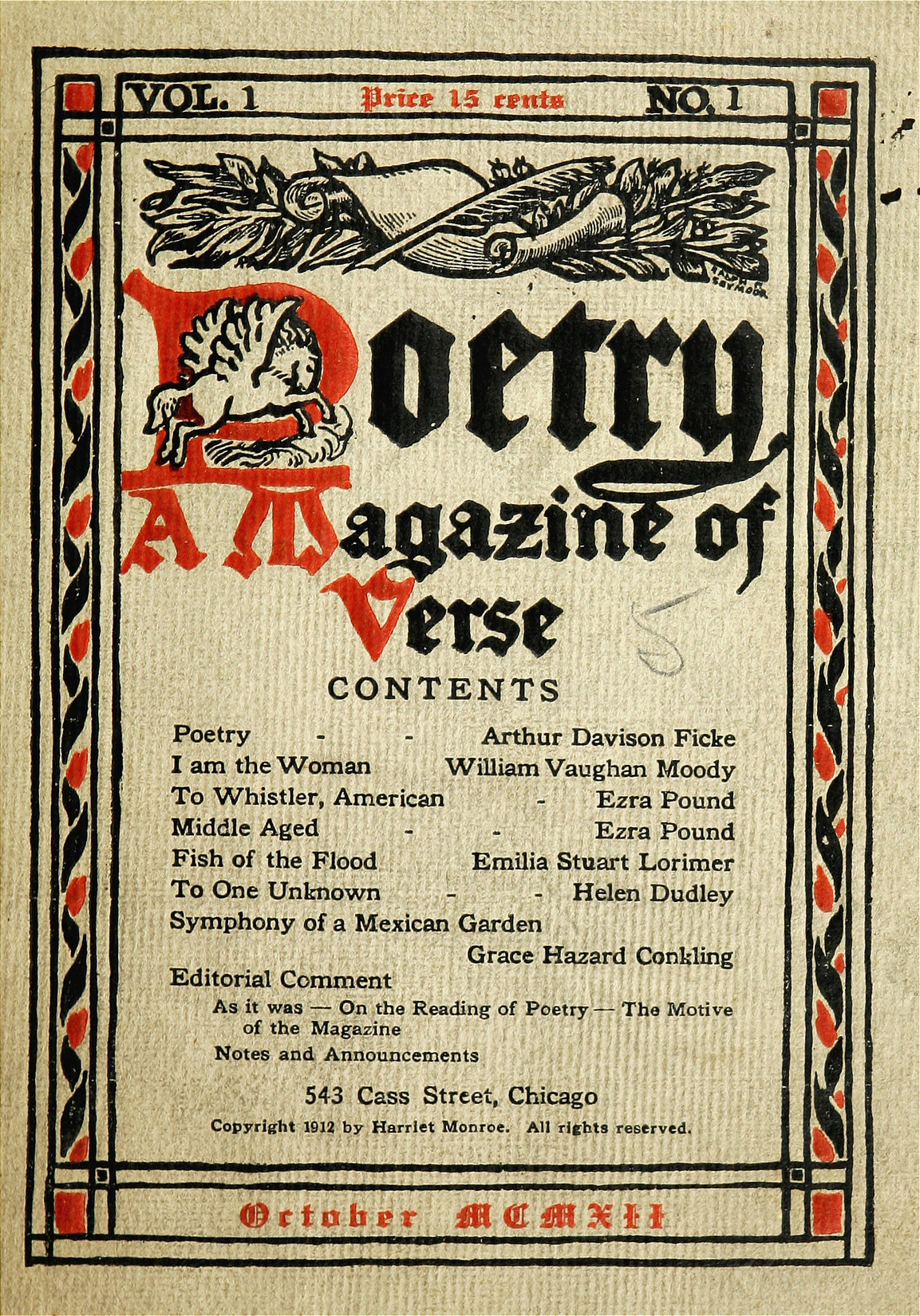

This is a real online treasure trove, facsimile editions, page by page, of the first ten years of Harriet Monroe's Poetry Magazine. I'm going to try and work my way through a play-by-play, issue by issue, which may take a while, and is certainly a quixotic endeavor. Still, a journey of a thousand poems starts with a single metaphor, so let's look at Issue 1, from October 1912, priced at 15c, and beginning, not with a manifesto (although there is a statement of purpose at the end), but with a poem -- a tw0-sonnet sequence by Arthur Davison Ficke. best remembered now for being Witter Bynner's co-conspirator in the Spectrist Hoax of a few years later.

How forward-looking was Poetry? Well, we know how forward-looking it was -- the epicenter of Modernism, champion of Pound. But you wouldn't prove it by Ficke, who looked more toward the mid-Victorian uplift of a poet like William Ernest Henley. I don't demand that poetry reflect today's tastes -- in fact, I rather prefer it not to -- but I'm hard pressed to find much in Ficke's homilies about poetry, that "little isle amid bleak seas."

Curiously, it contains a typo -- Harriet Monroe must have agonized over that after it was off the presses -- a typo in the very first poem of the very first issue.

Ficke goes on to compare poetry to a holy war, which makes it a manifesto of sorts. He's followed by William Vaughn Moody, the late William Vaughn Moody at this point -- he died young, of brain cancer, in 1910, leaving behind

one play, yet so full of promise was The Great Divide, so American in the best sense, that his early death cannot but be the source of the deepest regret.His posthumous entry here is mid-Victorian, too, but it looks back toward a more promising model, Robert Browning. He has some of Browning's pomposity, and some of his gift for characterization -- the woman of Moody's "I am the Woman" is more archetypal than Browning's finely tuned individuals, but at least she doesn't roar or bring home the bacon and fry it up in a pan. Moody gives us some nice metrical variations between iambs and anapests, and some nice rhetorical flourishes, like this chiasmus:

I comfort and feed the slayer, feed and comfort the slain.He remains readable.

Then, on page 11, we get to what we've been waiting for -- the leap into the future, with Ezra Pound. He leads off with an homage to Whistler that reads too much like most homages and most poems about art. He singles out Whistler and Abe Lincoln from the "mass of dolts" that populate and have populated America.

Then "Middle Aged: A Study in Emotion" takes from romping tourists down into the sarcophagus of a long-dead king, but Pound's snobbery gets subsumed in the sudden brilliance of insight and imagery, and here we are, moving into the 20th Century.

And back next time with more.As the fine dust, in the hid cell beneathTheir transitory step and merriment,Drifts through the air, and the sarcophagusGains yet another crustOf useless riches for the occupant

No comments:

Post a Comment