LISTEN TO ONE: Parchman Farm

Clarksdale, Mississippi, is one of the most important addresses in the history of the blues, having been home to Muddy Waters, Son House, John Lee Hooker, Ike Turner, Sam Cooke, Junior Parker, and many others. Today it is a tourist destination, as people come from around the world to visit the Delta Blues Museum or the crossroads where Robert Johnson had his famous mythic meeting with the Devil. But in the early and mid-20th century it was a place to leave, a jumping-off point for the Great Migration, as its future blues legends were to depart for Memphis or Chicago, where they could find audiences and radio stations and record companies.

LISTEN TO ONE: Council Spur Blues

One who stayed was Wade Walton, who would build a life and a business in Clarksdale, and become a civil rights leader and an early member of the NAACP.

It was a decision grounded in reality. Even most successful blues singers made a very uncertain living from the blues, and creative accounting meant that they saw little or no royalties from even a hit record. But Walton's barbershop became a Clarksdale institution. The barbershop was a community center in those days, and Walton's presence made whatever shop he worked in, from the Arnold Brothers and the Big Six barbershops in the center of Clarksdale, to eventually owning his own shop.

|

And he was more than a local institution. Blues superstars like Ike Turner and Howlin' Wolf and Sonny Boy Williamson would come back to Clarksdale to get their hair cut, and poet Allen Ginsberg got a haircut from Walton.

One of the reasons Walton's shop was so popular, in addition to his skill with the razor and scissors, was the music. Walton had grown up playing music. His boyhood home was the Goldfield plantation in Lombardy, Mississippi, in the shadow of Parchman Farm, and he and his brothers used to play impromptu concerts outside the prison fences. When he moved into town and chose barbering as a career over music, he kept his guitar and harmonica close at hand in the barbershop, and would give impromptu concerts there, too, on those two instruments and a third -- a straight razor and razor strop, used as a rhythm instrument.

Walton came to be known to the blues collectors who began combing the South as the blues revival got under way. Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records and British blues scholar Paul Oliver came to Clarksdale in 1960 to record him in the Big Six barbershop. They got a bonus from a customer at the time, Robert Curtis Smith, who also played and sang the blues, and whom they also recorded.

In 1961, both Walton and Smith recorded for Prestige Bluesville. The recordings appear to have been set up by blues collector Dan Mangurian, who had first met Walton on a trip to Clarksdale in 1958. The jazzdisco website, a remarkably accurate source for studio recordings by most of the independent jazz labels, is sometimes a little vaguer on field recordings. They list both Walton's and Smith's sessions as having taken place in Clarksdale in the summer of 1962, but it seems almost certain that Walton, with Mangurian, came north to Bergenfield, NJ, by then the office headquarters of Prestige. Did Smith come with them? There's no indication that he did, although why would Prestige have recorded Smith independently of Walton? Stephan Wirz, the German blues scholar whose research is very thorough, says that Smith was recorded in Memphis on July 28, 1961 by Chris Strachwitz, and this would not have been the only Strachwitz session to have been licensed to Bluesville. Production credit, according to Wirz, is given to Strachwitz and Bluesville's Kenny

Goldstein, although Goldstein would not have been likely to have been in the field. Wirz lists the Walton session as having been recorded in Bergenfield in 1962, by Rudy Van Gelder, and that seems unlikely. If Van Gelder recorded it (he is also credited on the album sleeve), it certainly would have been done in Englewood Cliffs. The album cover credits Goldstein as the producer. Wirz notes Mangurian and his partner Don Hill as uncredited producers.

Mangurian's and Hill's first meeting with Walton is documented in the song "Parchman Farm," on the album. This is very different from Mose Allison's "Parchman Farm," and much more up close and personal. Mangurian describes the genesis of the song in the album's liner notes:

"Parchman Farm" is a dramatization of a very real incident involving Wade, myself, and Don Hill...on our summer vacation [from Pomona College in California], Don and I traveled to the South to record folk music and blues in the field. We found Wade in Clarksdale and, while recording, we mentioned that we wanted to go down to Parchman Farm...to record the prisoners singing their work songs. Wade generously offered to take the next day off from work and ride down with us, since he was familiar with Parchman Farm from his childhood days.

Late the next morning we drove the 25 miles down Highway 49 to Parchman. We got a visitor's pass at the main gate and drove down to the chaplain's house figuring he would know the prisoners better than anyone else and help us out. The chaplain, however, was very uncooperative and sent us down to the administration building to wait for the educational director to return from lunch.

We didn't wait long before a stocky man with a .38 at his side stormed in. This was Mr. Harpole, a staunch segregationist as it turned out, who was then assistant warden and noted for his cruelty toward the convicts with his three foot leather strap. He asked us a few questions, then turned on Wade, saying "Boy, if you know'd like I know, you'd be out of here runnin'," and bluntly ordered Don and me to leave with the advice that "we should have known better to come in here with a n*****."

...The incident made a lasting impression on Wade, who later made up this song, weaving together the events in a loose rhyming way. The guitar depicts the seriousness of the situation (which Don and I were naively unaware of) he felt when Mr. Harpole arrived...He ends by saying "We left Parchman Farm, didn't get no race relations done."

Mack McCormick wrote the liner notes for Robert Curtis Smith's Bluesville album. Although

McCormick was unable to resist one more little gratuitous dig at Lightnin' Hopkins ("Unlike many a more fortunate blues singer, there is little self pity in this man"), he did paint a vivid and detailed picture of Smith's life as a Black laborer in Mississippi of the 1940s and 1950s, with a few telling but gruesome asides (Smith's home is a few miles from where Emmett Till was murdered). He describes in some detail the background to Smith's "Council Spur Blues," starting with a landowner named Roy Flowers, "whom Smith describes as 'rich man, but he don't pay nothin.'" Flowers followed what was then a common course of action -- wait for a Black man to get arrested, then go his bail, then tell the Black man that he was indebted to pay off the bail expense -- at a rate dictated by the white man.

Smith had to work for Flowers on the Council Spur plantation.

There he is kept on short rations, in debt to the plantation store and subject to the antics of an overseer who... refuses to let tenants have private vegetable gardens.

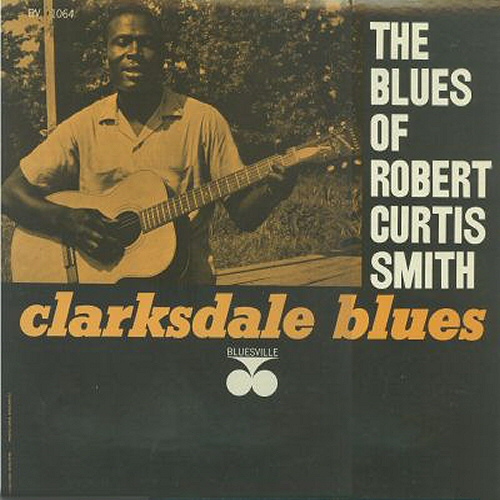

Smith's album is called The Blues of Robert Curtis Smith--Clarksdale Blues. His repertoire is bluse songs picked up from local bluesmen and the radio. Walton's is The Blues of Wade Walton--Shake 'em on Down. "Memphis Mango," credited as second guitar on the album, is Dave Mangurian. His songs are familiar blues material and some of his own composition, including two instrumentals. On both these albums, the original compositions referenced in "Listen to One" are powerful socio-historical documents as well as being powerful songs. Both are on Bluesville.

Walton's leadership in the local NAACP and his advocacy for civil rights led to his barbershop being bombed, but he rebuilt, kept working for the cause, and kept cutting hair, making a decent living from a Black-owned business that he never would have gotten from the recording industry. He was voted into the Clarksdale Hall of Fame in 1989, and died in 2000.

No comments:

Post a Comment