Well, not quite. And once again the story goes back to Detroit, and Cass Technical High School. As Byrd remembered it in a 1998 lecture at Cornell University, one of the many institutions at which he taught,

I met him in the 11th grade in Detroit. I skipped school one day to see Dizzy Gillespie, and that’s where I met Coltrane. Coltrane and Jimmy Heath just joined the band, and I brought my trumpet, and he was sitting at the piano downstairs waiting to join Dizzy’s band. He had his saxophone across his lap, and he looked at me and he said, ‘You want to play?’

So he played piano, and I soloed. I never thought that six years later we would be recording together, and that we would be doing all of this stuff.

And in fact, not even close. Byrd and Coltrane recorded together more than I would have guessed. Here's the best I can do for a complete list, relying on information from the amazing New York Public Library Research Desk, Wikipedia, jazzdisco.org, and Amazon:

And in fact, not even close. Byrd and Coltrane recorded together more than I would have guessed. Here's the best I can do for a complete list, relying on information from the amazing New York Public Library Research Desk, Wikipedia, jazzdisco.org, and Amazon:

Elmo Hope All Star Sextet, Informal Jazz (Prestige, May 1956) With Hank Mobley, Paul Chambers, Philly Joe Jones

Paul Chambers Sextet, Whims of Chambers (Blue Note, September 1956). With Kenny Burrell, Horace Silver and Philly Joe Jones.

Art Blakey Big Band (Bethlehem, December 1957). They were featured on two tracks as the Art Blakey Quintet, playihg a composition by Byrd and one by Trane.

Sonny Clark Sextet, Sonny's Crib (Blue Note, October 1957). With Curtis Fuller, Paul Chambers and Art Taylor

John Coltrane Quintet, Lush Life, Black Pearls (Prestige). These were both from the Coltrane compilations issued after Trane had left Prestige. Lush Life included one cut from a January 1958 session with Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Louis Hayes. Black Pearls was a May session with Garland, Chambers and Art Taylor.

Oscar Pettiford All-Stars, Winners Circle - Down Beat Poll Winners from 1956 (Bethlehem, October 1957). With Gene Quill, Al Cohn, Freddie Green, Eddie Costa, Philly Joe Jones and Ed Thigpen in various mix-and-match combinations.

And, since we were just talking, in the context of Mose Allison, about musicians getting duped out of publishing rights, here's another Donald Byrd story, this time with Byrd as the voice of experience, and Herbie Hancock as the callow youth. When Byrd gave Hancock his recording debut on a Blue Note session, Blue Note wanted to sign the young pianist to a recording contract, and Byrd warned him that under no account should he surrender the publishing rights to his music. So of course, that was the first condition Blue Note made.

A recording contract isn't just a temptation to a young musician, it's the temptation. That's why so many young musicians give away so many rights. And it seemed inconceivable to Hancock that he could walk away from it, but he did. Blue Note caved. Hancock kept the publishing rights, and when Mongo Santamaria had a hit with "Watermelon Man"...well, the rest of the story comes not from a music publication, but from Road and Track (by way of Wikipedia). Hancock took the royalties from "Waterm

elon Man" and bought a Shelby Cobra, which is now renowned as the oldest production Cobra still in the hands of its original owner.

elon Man" and bought a Shelby Cobra, which is now renowned as the oldest production Cobra still in the hands of its original owner.Of course, the real story here is the music. There's one new name, George Joyner, who would not have that name for long. He had come to New York after a stint playing the blues with B. B. King, and recorded first with Phineas Newborn. After converting to Islam, he became first Jamil Sulieman and then Jamil Nasser, and had a long association with Ahmad Jamal, and a career that went well into the 90s;

This was a long day in the studio, which would have come as no novelty to Garland and Coltrane, who were both on board for the Miles Davis Contractual Marathon. Ten songs, and one of them, "All Mornin' Long," went on pretty much all evening long, clocked in at 20 minutes, and made up a whole side of one of the LPs to come out of the session. And even after that, they weren't quite willing to call it a day, as they came back the next month to do five more.

"All Mornin' Long" was a Garland composition, and although it was the last piece recorded that day,

it was the first side of the eponymous first album released from the session. It holds attention all the way through, particularly the long piano solo by Garland that features some beautiful dialogue with Joyner/Nasser, leading into a bass solo that makes you understand why this guy was welcomed into the fold. Two other pretty fair composers took up the second half, George Gershwin ("They Can't Take That Away From Me") and Tadd Dameron ("Our Delight").

All Mornin' Long was a pretty quick release, in the spring of 1958. The others were a little longer in coming. Soul Junction saw the light of day in 1960, again with the Garland composition giving the album its title. Garland shared composing space with jazz giants: two by Dizzy Gillespie ("Woody'n You" and "Birks Works") and one by Duke Ellington (I've Got it

Bad"). The final composer honors for the album went in a different direction, to 1920s Broadway composer Vincent Youmans, but Youmans might not have recognized their bopped-out, uptempo, nonstop version of his "Hallelujah." It's a rousing enough tune, as performed by Glenn Miller and others, but not always this rousing.

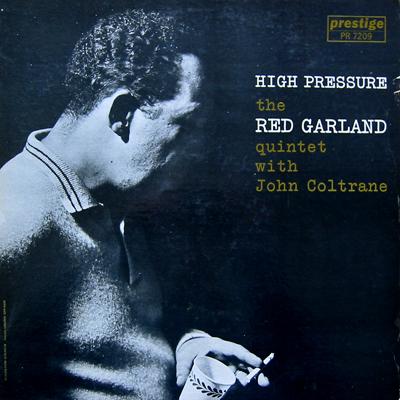

The rest of the November session--"Undecided" (Charlie Shavers) and "What Is There to Say?" (Vernon Duke)--had to wait until High Pressure in 1962, along with three songs from the December session: "Soft Winds" (Benny Goodman / Fletcher Henderson), "Solitude" (Duke Ellington) and "Two Bass Hit" (Dizzy Gillespie/John Lewis). When you're getting together to play that much music, without much rehearsal, it's probably a good idea to mostly choose tunes that everyone knows. Bird's "Billie's Bounce" and Garland's "Lazy Mae" were on a later 1962 LP called Dig It!, which put together numbers from three different sessions.

No comments:

Post a Comment