What does that mean, anyway? I know that heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter. I know that one of the myriad reasons why the novel, The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, is better than the movie is that you can imagine the unbearable sweetness of "Beautiful Maria of My Soul," whereas in the movie there's an actual song, composed by Robert Kraft, who's a perfectly good composer, but it's just another song, not the worst you've ever heard but not the best either.

But none of that is about the notes you don't play. When I first heard In a Silent Way, I was stunned by Miles's restraint--how much he held back from playing, and how powerful the parts that he did play. But I can't tell you anything about the notes he chose not to play, because I didn't hear them. And I'm not sure I believe that there were any notes that he chose not to play. There were times that he held back from playing, but that doesn't mean there were sequences of notes that he heard in his head and chose not to play.

And Miles didn't exactly invent not playing. Max Roach, talking about how effective George Wallington was as a piano player in the early bebop groups, said

We needed a piano player to stay outta the way. The one that stayed outta the way best was the best for us. That's why George Wallington fitted in so well with us, because he stayed outta the way, and when he played a solo, he'd fill it up; sounded just like Bud.

And Miles, famously, told Monk to lay out while Miles was playing his solos. Monk, significantly, let Miles know that while he was laying out, he was just staying outta the way, he was not carefully choosing meaningful unplayed notes."

I used to tell my creative writing students "know everything, and write ten percent of what you know," which I either borrowed from Hemingway or pretended I had. But if you're doing that, what ultimately counts is the ten percent that you write, not the ninety percent you leave out.

The NYRB article goes on to say that

Davis shed styles as soon as they risked settling into formula. When “cool” lost its edge in the hands of white West Coast musicians, he pioneered hard bop, a simplified, funkier style of bop that reasserted jazz’s roots. When hard bop hardened into its own set of sweaty clichés, he gravitated to “modal” jazz, which used scales rather than chord changes as a harmonic frame.Miles had a restless muse, and it made him what he was, and some of his experiments were more successful than others, but a genre of music doesn't automatically become worthless just because Miles Davis stops playing it. "Cool" didn't simply lose its edge because Gerry Mulligan (who was in with Miles at the creation) went out to the West Coast and kept playing it, and when Jackie McLean's pal Bill Hardman led a hard bop group (with Junior Cook) into the early 1980s, he was playing exciting music, not sweaty clichés.

We are still relatively early in the hard bop era, an era defined by having no particular starting point and no particular ending point, and having no particular defining characteristics. It was jazz, or as Miles insists on calling it in the recent Don Cheadle movie (music direction brilliantly handled by my pal Ed Gerrard), "social music." The society of the men and woman who made this social music was eclectic and original and committed to musical exploration wherever it took them.

And there's an interesting bit of exploration here, right at the start of this set. We just recently listened to the Mal Waldron composition, "Flicker" (or "Flickers" -- it seems to go by both names) as played by a Prestige All Stars group augmented by Kenny Burrell and Jerome Richardson, and here we have it again by Prestige stars Jackie and his pal, the All Star Waldron-Watkins-Taylor rhythm section, this time augmented by tuba virtuoso Ray Draper. In the first version, the head is played as almost a fanfare, which then gives way to the nimble dexterity of Burrell's guitar and Richardson's flute.

In Jackie's version, the fanfare is still there, but he takes a more melodic approach. And where Burrell went into the air with a flute, McLean comes down to the ground with a tuba, providing an earthy cushion right from the start. He also takes a solo, between Bill Hardman and Mal Waldron, and all three of these solos add something new. It's fitting that Waldron, the composer, takes the last one, giving a special insight into the melody.

Draper is on two cuts: this one, and his own composition, "Minor Dreams." This is an impressive recording debut for a young musician, made all the more impressive when you consider how young: Draper was 16.

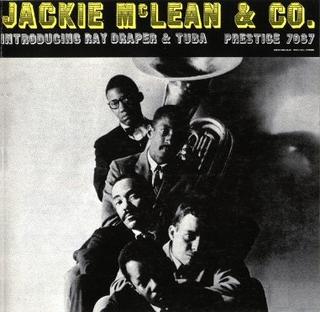

Jackie McLean, who knew something about how hard it is to break through in the music business, seems to have made a commitment, not only to introducing new talented musicians, but to making sure they got fulll recognition (Jackie certainly knew something about getting less than full recognition). We've seen how he introduced his pal, Bill Hardman, on Hardman's recording debut. The full title of this album is Jackie McLean and Co., Introducing Ray Draper and Tuba. The "introducing" part was left off when the album was rereleased on New Jazz, but by that time Draper had introduced himself on his own Prestige album.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

No comments:

Post a Comment