In 1956, Blind Willie McTell was singing on the streets of Atlanta. He was recorded by a local record store owner, but before the recordings could ever find a label or be released, McTell was dead.

He died in 1959. Bob Weinstock founded his Bluesville subsidiary in 1960, which was actually a little ahead of the curve. King of the Delta Blues Singers, the rerelease of Robert Johnson's Vocalion recordings of 1936 and 1937, didn't come until 1961. Charley Patton, one of the earliest pioneers of Delta Blues, had his reissue in 1962, 28 years after his death.

The Blues Hall of Fame started recognizing the titans of the Blues in 1980, did not get an actual building until 2015.

In 1940, John Lomax had recorded McTell for the Library of Congress Archives. He would do very little recording in the intervening years.

Recorded blues had an odd and spotty history. The first blues recording came out in 1920. An African American songwriter, Perry Bradford, one of the very few composers working on Tin Pan Alley, the tight cluster of New York music publishing firms that produced most of America's popular music in the first quarter of the 19th Century. had written a song called "Crazy Blues." He first offered it to Sophie Tucker, one of the most popular singers of her day, but she wasn't looking at any new material just then. A couple of other singers passed on it, so Bradford suggested recording it with a colored singer. The response: Bradford was crazier than his blues. No one would ever by a record by a colored singer. But they did take a chance and record "Crazy Blues" with Mamie Smith, and it was a smash, and it started the blues craze of the 1920s. But the Depression forced cutbacks in the recording industry, and the black performers were the first to be cut.

The real return of recorded blues was post-World War II, and it was part of the developing interest in

folk music (the vital electric blues being recorded in Chicago, Detroit and Los Angeles was considered commercial and inauthentic by the folkies). And this made for an interesting development, since the blues was essentially a music of realism, with the underlying message that things were never going to get better, and the white leftists who were a great part of the folkie audience believed that we could get together and make a better world.

The blues that were to become the center of the new blues explosion were from the Mississippi Delta. Delta musicians like Muddy Waters and Sonny Boy Williamson made their way north to Chicago, where they created an electric blues style that folk purists wanted nothing to do with. Musicians from Oklahoma and Texas went to Los Angeles, where they created their own electric style (T-Bone Walker was one of the pioneers of the electric guitar). There was much less of a blues scene in New York, always more of a jazz town, hospitable to jazz-based blues singers like Bessie Smith. The blues musicians who came to New York were mostly from the East Coast, and played in a style that came to be known as Piedmont blues, which was characterized by many things, but one of them was that many of its exponents, like Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, sang in accents that were easier for the mostly white folkie audience in New York than the heavier accents of Delta bluesmen like Charley Patton. The Delta bluesmen would soon be championed by a new group, the blues purists, who were different in many respects from the folk purists. Brownie McGhee had been recorded by Bob Weinstock early in his career, when he was trying to make a name as a rhythm and blues singer.

All of this would change with the nascence of the blues purists, who were a different breed altogether from the folk purists, and the British blues imitators, who were not purists at all.

Blind Willie McTell was a Piedmont bluesman, and although Bob Weinstock was a jazzer rather than a folkie, this seems to have been one of the styles he gravitated toward. But I actually probably shouldn't be spending anywhere near this much time on McTell, since he wasn't one of Weinstock's recordees, or one of his first Bluesville releases, for that matter.

But he was a good pickup for Bluesville, and it's good that these late recordings are available. Bob Dylan sang that no one could sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell, but it may have been more true that no one's name fit the rhythm and rhyme scheme of his song like Blind Willie McTell's. McTell in many ways hearkened back to an earlier age. The black street singers in the South were "songsters," and they sang a bit of everything, including the blues. When the blues craze of the 1920s hit, the songsters became bluesmen. By 1956, McTell was still singing on the street, and he had some of the repertoire of the old songsters, like "Wabash Cannonball," a 19th century ballad popularized by country and western pioneer Roy Acuff. It was cool to hear it done with a blues twist.

Also on the session, "Beedle Um Bum," which had been recorded by Tampa Red and McKinney's Cotton Pickers.

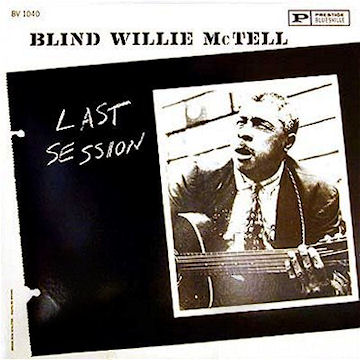

The Bluesville album was released in 1962 as Last Session. The following year, "Beedle Um Bum" made a reappearance on a compilation album called Bawdy Blues.

Anyway, more about Bluesville and Bob Weinstock's blues when we get to 1960.

No comments:

Post a Comment