What's now known as the First Quintet jelled in the fall of 1955, when John Coltrane replaced Sonny Rollins, They appeared on the Steve Allen show in October, did their first studio session for Columbia a week later, and made their first recording for Prestige in November.

So by the time they got together for their first Contractual Marathon, they'd been working together for half a year. How long does it take a group of brilliant jazz musicians to coalesce? Well, we've just listened to the Elmo Hope session with Coltrane, Hank Mobley and Donald Byrd, so we know the answer is that you can just all wander into Rudy's parents' living room on a nice spring day and start playing seamlessly intuitive jazz right off the bat. Of course it helps if you have a great rhythm section, and one was there that day: Elmo Hope, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones.

How much does it help? Jack Maher, in the liner notes to one of the LPs to come out of this session, recalls a club date where Miles and Coltrane were hopelessly out of sync, and the music was almost unlistenable. Maher recalls that, sitting with Teddy Charles, he commented on it. Charles's response:

If it doesn't take long for a bunch of great jazz musicians to find a groove, it takes a little longer to simply know this many tunes in common. And that's where six months of club dates starts to matter. Most, if not all of the songs played on this and the following marathon session were ones that the group had played on the road, in clubs. A bunch of them were pieces that Miles had recorded before, including the one they started the session with, "In Your Own Sweet Way," which he had just done two months earlier in an abbreviated session with a quintet featuring Sonny Rollins. This version is maybe better -- starting right off with Miles and his Harmon mute, setting a tone for the whole session."Watch the rhythm section. This is the best rhythm section in jazz the hardest swinging rhythm section, watch out when they loosen up."At this point Miles and Coltrane abruptly walked off the stand. This was the usual cue for Red Garland to his featured number-trio style. Miles did this regularly when he was bored, felt he needed a break or a beer. I don't remember what tune it was exactly, something like "Ahmad's Blues" in this album, if I'm not mistaken, a medium tempo that more or less plays itself.From the beginning the three men relaxed. Alone on the stand Red, Paul and Philly Joe relaxed and fell into a smooth spirited swing. The trio drew more applause for that one tune than the whole group had for the entire evening. When Miles and Coltrane returned to the bandstand the atmosphere in the club had changed. Somehow the tension had gone, and, on the next tune, "It Never Entered My Mind", which is also performed in this album, Miles played one of the most beautiful choruses I've ever heard him play.

I don't think he'd ever recorded "Diane" before. It wasn't exactly a jazz standard, and hasn't exactly become one, although Pete and Conte Candoli did a West Coast version a few years later. It was composed by Erno Rapee, primarily a symphonic composer. Its best known recording was by Mario Lanza, and it's not one of Lanza's best numbers. In fact, although it's been widely recorded by vocalists as far-ranging as country singer Jim Reeves, it really doesn't seem like a very good song. Until Miles gets hold of it. And Coltrane, who'd had a lovely solo on the first cut, really steps out and wails here, as he does on "Trane's Blues," which sort of makes its recorded debut here--that is, first recording under this title. It was called "Vierd Blues" when Miles and the same rhythm section, plus Sonny Rollins, recorded it in March, and composer credit was given to Miles. And also in March, it was recorded for a West Coast label by a group under Chambers' name, featuring Coltrane, Jones and Kenny Drew, as "John Paul Jones," for reasons that should be self-explanatory.

Going back and listening to both versions of "In Your Own Sweet Way" again, something occurs to me. Rollins is capable of as much romanticism as Davis is. So is Tommy Flanagan, actually. And Miles holds back a little. In the quintet version, he's matched with John Coltrane, who is following his own muse, which will take him, as we know, into remarkable places. But even here, he's into his own explorations, and this gives Miles license to completely open up to the romantic side of his nature. Listen to the way Miles comes back in at the end "In Your Own Sweet Way," after Coltrane's solo, simplifying, finding all the sweetness in the melody.

And I think this is one of the reasons why the albums that came out of these sessions were so popular at the time, and remain so popular. We've listened to the Davis/Charlie Parker recording session of 1953, where they ran out of studio time, and had to record "Round Midnight" in fifteen minutes. I said of that recording, "No time to be clever, no time to intellectualize it. Just go with the emotions closest to the surface, and for Parker pain was never far below."

Miles doesn't have a lot of time here, and maybe he's taking the most direct route. He's doing what Chuck Berry says modern jazzers don't do: trust the beauty of the melody.

But maybe he's doing it because he knows he can. He's been playing with Coltrane, Garland, Chambers and Jones for six months now, and he trusts them to provide a framework. Maybe that's one of the reasons why he chose so many ballads for this session.

"Something I Dreamed Last Night" is the first of these. It's a Sammy Fain melody that's been done

often by vocalists, starting with Marlene Dietrich, who is never simply romantic. There's always the subtext that she knows more about life than you'll ever know. Sarah Vaughan is surrounded by strings for her version, which makes for romance, but Sarah always has an edge, too. She always sings the song, and does it justice--more than justice--but she's also always singing the music, making a statement about it. Miles does that too, of course, but somehow he stays closer to the emotional purity. Johnny Mathis is all about beauty and emotion, but Mathis, as good as he is, is a bit of a one-trick pony -- beauty and emotion is what he's always going for. For Miles, it's a choice. And that brings a special kind of intensity.

There's probably no one who's never recorded "It Could Happen to You," starting with Dorothy Lamour in a 1944 movie. There's probably no way to sentimentalize a song more than Lamour does, even though she sings it to Fred MacMurray, and Miles finds a drier, more emotionally ambiguous approach, as he does with "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," the Rodgers and Hammerstein paean from Oklahoma to a bucolic life that Miles never knew nor wanted to know. In both of these, he sets up Coltrane for adventurous and bopworthy solos.

He gets back to the achingly beautiful with "It Never Entered My Mind," a song from the other side of the Richard Rodgers songbook, the dark side that Lorenz Hart explored, as opposed to Oscar Hammerstein's sunny side. Hart's lyrics capture the devastating loss of love to a guy who maybe deserved it, but that doesn't make the loss any less painful, especially since he knows he deserves it. Miles gives us the loss, in its purest form. He lets Red Garland explore other emotions, and then he brings it back to the melody, and the simple emotion. "When I Fall in Love," written by Victor Young for a forgettable 1952 movie, is nowhere near as good a song, but Miles finds the pathos in it, and makes the melody better than it perhaps has a right to be. There'll be more ballads in the next and final chapter of the Contractual Marathon, and they'll be beautiful too.

Then there are bebop classics (Dizzy Gillespie's "Woody'n You" and "Salt Peanuts," Miles's "Four"). They're treated like old friends, and they give all the satisfaction of hanging out with old friends...who have something new to say. Philly Joe Jones takes over "Salt Peanuts" and leaves you breathless. There's no chanted "Salt Peanuts! Salt Peanuts!" but Miles's horn gives a pretty good approximation.

Garland, Chambers and Jones are given the spotlight on "Ahmad's Blues," including a gorgeous bowed bass solo by Chambers. They demonstrate what Teddy Charles was talking about, and they demonstrated it to Bob Weinstock too -- he signed them as a trio.

Miles was a huge fan of Ahmad Jamal, and a lot of jazz critics thought Miles was crazy. Jamal played a lot of gigs in Chicago, which automatically put him the Second City second rank, and he mostly played with a trio in cocktail lounge settings, which made it easy to dismiss him as cocktail pianist. It should come as no surprise to find out that Miles was right.

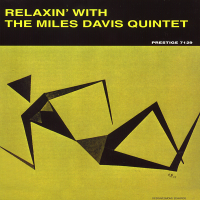

The contractual sessions were cut up and released on four different albums over the next few years. "Woody'n You" and "It Could Happen to You" were on the March 1958 release, Relaxin' with the Miles Davis Quintet (the first release, Cookin' in 1957, was all tunes from the later session).

"In Your Own Sweet Way," "Trane's Blues," "Ahmad's Blues," "It Never Entered My Mind," "Four" and the two versions of "The Theme" came out on the 1959 release, Workin' with the Miles Davis Quintet.

"Diane," "Something I Dreamed Last Night,""Surrey with the Fringe on Top," "When I Fall in Love" and "Salt Peanuts" were all held off until 1961 and the final LP from the 1956 sessions, Steamin' with the Miles Davis Quintet.

A number of these tunes also eventually found their way to 45 RPM singles, as Prestige really entered that game in the 1960s. "It Never Entered My Mind" came out in early 1960, divided onto two sides of a 45, and July of 1960 saw "When I Fall in Love"/"I Could Write a Book." The marketing folks at Prestige had apparently decided that two songs were a better sell than Parts 1 and 2, which meant that These long form LP improvisations were released in edited versions. "When I Fall in Love," at 4:21, could easily have been split in half, but instead it was cut down to 2:25. Same with "I Could Write a Book," which went from 5:11 t0 3:37.

A number of these tunes also eventually found their way to 45 RPM singles, as Prestige really entered that game in the 1960s. "It Never Entered My Mind" came out in early 1960, divided onto two sides of a 45, and July of 1960 saw "When I Fall in Love"/"I Could Write a Book." The marketing folks at Prestige had apparently decided that two songs were a better sell than Parts 1 and 2, which meant that These long form LP improvisations were released in edited versions. "When I Fall in Love," at 4:21, could easily have been split in half, but instead it was cut down to 2:25. Same with "I Could Write a Book," which went from 5:11 t0 3:37."Surrey with the Fringe on Top"/"Diane" was released in April or May of 1963, as Prestige continued to space out the contractual sessions as far as they could. Both of these were in severely edited versions -- the originals had been 9:05 and 7:49 respectively. For that matter, on "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," they edited the "e" out of "Surrey."

1 comment:

When the software becomes more complex, it can be more difficult, time-consuming, and boring to identify bugs. So, to make fewer mistakes and accelerate the entire development process, we use automated testing, where both developers and QA engineers write tests. https://cxdojo.com/how-unit-tests-can-improve-your-product-development

Post a Comment