This is the second half of the Earl Coleman Returns session, with Art Farmer and Hank Jones returning along with Earl. Gigi Gryce is absent, and there are a new bass and drums.

The more I listen to Earl Coleman, the more I like him. I'm hearing a much more modern sound than I did before, and I expect that has to do with me more than Earl. The Mr. B. and Al Hibbler influences are still there, as is probably appropriate from a singer returning from the Forties, but I'm hearing a little Jon Hendricks as well, and maybe a little Joe Williams, Mostly, I'm hearing a distinctive singer.

Gigi Gryce hasn't left the building completely. "Social Call," probably the gem of the session, is a Gryce composition. And there's perhaps a reason for the Hendricks echo. He wrote the lyrics. "Social Call" has become a favorite of jazz instrumentalists and singers alike.

This version of "Social Call" also has beautiful solos by Art Farmer and Hank Jones, and that, I would say, tells you something about Coleman's musicianship.

Wendell Marshall was a veteran of the Ellington band, but I hadn't known his other Ellington connection -- he was the second member of his family to play bass for the Duke. His cousin was Jimmy Blanton. He had steady work as a Broadway pit musician, and was also one of the most sought-after session bassists.

Wilbur Hogan, also known as Wilbert Hogan and G. T. Hogan. like Marshall, could play both bop and R&B, and did a lot of work in the 50s and 60s, until health issues slowed him down..

Nothing from this album on YouTube, but I found "Social Call" here. It is very much deserving of a listen. This is a singer who should not be forgotten.

Tad Richards' odyssey through the catalog of Prestige Records:an unofficial and idiosyncratic history of jazz in the 50s and 60s. With occasional digressions.

Tuesday, February 23, 2016

Sunday, February 21, 2016

Listening to Prestige Part 173: Gil Melle

Gil Melle is probably best known to jazz history as the guy who introduced Rudy Van Gelder to Blue Note's Alfred Lion. The session never made it to wax, but the recording quality was good enough to draw Lion, and then Bob Weinstock, out to Hackensack.

Melle did eventually record several albums for Blue Note, and a few for Prestige, starting with this one, recorded in two sessions. I wasn't able to listen to any of the April tracks, so I'm getting to the whole album here.

Melle was multi-talented, a graphic artist as well as musician.

His work was shown in New York galleries, and he designed a number of jazz album covers. His career at this time could be compared to that of Pop artist Larry Rivers, but Rivers was an artist first and a jazz hobbyist; Melle's main focus was music, although he also continued to paint all of his life, and he eventually moved to the West Coast, where he launched a successful career as a composer of film and TV scores, including The Andromeda Strain and Rod Serling's Night Gallery. The theme music for the 1970 TV show was the first ever to use all electronic instrument, and The Andromeda Strain, in 1971, was probably the first all-electronic movie score.

This quartet session for Prestige uses all traditional instruments, but listening to it, it's not surprising that Melle would grow fascinated with electronic instruments, designing and building many of them himself, and presenting the first ever all-electronic jazz ensemble at the 1967 Monterey Jazz Festival. He's more concerned, especially in "Dominica," with tonal quality, and at first listen, one wonders if he's trying too hard, and intellectualizing the process too much.

On subsequent plays, however,the music becomes much more rewarding, and the ensemble is remarkable.

It's also a little puzzling. The Jazzdisco set list has Melle playing baritone and alto sax, and Bill Phipps playing bass. But Phipps was a baritone sax man, so it could be that he is, in fact, the one on baritone. If he's not, Melle is double-tracking himself, and given his interest in electronic sounds, that's certainly possible. but I think not likely.

So let's give Phipps the credit for some intriguing baritone sax work, and move on to him, as one of an ensemble of little-known (except for Ed Thigpen) and fascinating musicians.

Except for his work with Melle, Bill Phipps wasn't much of an avant-gardist, although he did once lead a band that featured Grachan Moncur. In fact, he came from a jazz family that was deeply rooted in the tradition. His cousins Ernie and Eugene led a band called the Monarchs of Swing. He and his brother Nat cp-led the group that featured Moncur and Wayne Shorter, and Bill later played with such earthy ensembles as Ray Charles' and Brother Jack McDuff's.

But here with Melle, he understands the demands of the avant garde, and delivers.

Joe Cinderella delivers more than his share, especially on "Ballet Time," my favorite of the set. It also has Melle's strongest soloing.

Joe Cinderella delivers more than his share, especially on "Ballet Time," my favorite of the set. It also has Melle's strongest soloing.

Where did Melle come up with these guys? Every one of them, it seems, has at least one toe in both the mainstream and avant garde. How avant garde was Joe Cinderella? He worked with John Cage. Avant garde enough for you? He also worked with Warne Marsh. On the mainstream side of jazz, he worked with Conte Candoli, and deeper into the mainstream of American music, he played on sessions with the Beach Boys and Billy Joel. He's pretty much forgotten today, but he's worth seeking out.

Ed Thigpen is certainly the best known musician in this quartet. Mostly known for his mainstream work with Oscar Peterson, Billy Taylor and Ella Fitzgerald, he also played with Lennie Tristano, who is the godfather of the sort of music Melle plays. He's also from a musical family -- his father played with Andy Kirk's Clouds of Joy.

This album was released, for reasons best known to Gil Melle, as Melle Plays Primitive Modern.

Melle did eventually record several albums for Blue Note, and a few for Prestige, starting with this one, recorded in two sessions. I wasn't able to listen to any of the April tracks, so I'm getting to the whole album here.

Melle was multi-talented, a graphic artist as well as musician.

|

| Album cover art by Gil Melle |

This quartet session for Prestige uses all traditional instruments, but listening to it, it's not surprising that Melle would grow fascinated with electronic instruments, designing and building many of them himself, and presenting the first ever all-electronic jazz ensemble at the 1967 Monterey Jazz Festival. He's more concerned, especially in "Dominica," with tonal quality, and at first listen, one wonders if he's trying too hard, and intellectualizing the process too much.

On subsequent plays, however,the music becomes much more rewarding, and the ensemble is remarkable.

It's also a little puzzling. The Jazzdisco set list has Melle playing baritone and alto sax, and Bill Phipps playing bass. But Phipps was a baritone sax man, so it could be that he is, in fact, the one on baritone. If he's not, Melle is double-tracking himself, and given his interest in electronic sounds, that's certainly possible. but I think not likely.

So let's give Phipps the credit for some intriguing baritone sax work, and move on to him, as one of an ensemble of little-known (except for Ed Thigpen) and fascinating musicians.

Except for his work with Melle, Bill Phipps wasn't much of an avant-gardist, although he did once lead a band that featured Grachan Moncur. In fact, he came from a jazz family that was deeply rooted in the tradition. His cousins Ernie and Eugene led a band called the Monarchs of Swing. He and his brother Nat cp-led the group that featured Moncur and Wayne Shorter, and Bill later played with such earthy ensembles as Ray Charles' and Brother Jack McDuff's.

But here with Melle, he understands the demands of the avant garde, and delivers.

Joe Cinderella delivers more than his share, especially on "Ballet Time," my favorite of the set. It also has Melle's strongest soloing.

Joe Cinderella delivers more than his share, especially on "Ballet Time," my favorite of the set. It also has Melle's strongest soloing.Where did Melle come up with these guys? Every one of them, it seems, has at least one toe in both the mainstream and avant garde. How avant garde was Joe Cinderella? He worked with John Cage. Avant garde enough for you? He also worked with Warne Marsh. On the mainstream side of jazz, he worked with Conte Candoli, and deeper into the mainstream of American music, he played on sessions with the Beach Boys and Billy Joel. He's pretty much forgotten today, but he's worth seeking out.

Ed Thigpen is certainly the best known musician in this quartet. Mostly known for his mainstream work with Oscar Peterson, Billy Taylor and Ella Fitzgerald, he also played with Lennie Tristano, who is the godfather of the sort of music Melle plays. He's also from a musical family -- his father played with Andy Kirk's Clouds of Joy.

This album was released, for reasons best known to Gil Melle, as Melle Plays Primitive Modern.

Saturday, February 20, 2016

Listening to Prestige Part 172: Sonny Rollins/John Coltrane

This is two weeks after the May installment of the Contractual Marathon, and Miles may be resting up for the next assault, but the guys are still hanging around, and here is Teddy Charles's "best rhythm section in jazz" back in the studio to support Sonny Rollins.

And here, for one track, is the tenor player Miles hired when he couldn't get Sonny. These are two young men who are poised to become the dominant tenor saxophone players in jazz, the heirs apparent to Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster and Lester Young.

I realized, as I wrote that, that I had never been quite sure what "heir apparent" meant, so I looked it up. An heir apparent is the next in line for succession to a throne or a title, and is next in line no matter what. This is distinguished from an heir presumptive, who is next in line until someone comes along with a better claim. So in jazz, one would have to say that all heirs are heirs presumptive--they are one cutting contest away from being displaced as next in line to the throne. For that matter, jazz royalty are kings presumptive.

But these were the two, and time and history have moved them from presumptive to apparent to jazz royalty, and this one track, from this one recording session, is their only appearance on record together. Ever.

The tune is "Tenor Madness," and it has become a jazz standard...and not just for tenor players. On YouTube, you can find amazing renditions of it by Emily Remler and Toots Thielemans. Tenor players who have recorded it include Arnett Cobb and Joe Henderson, Dexter Gordon, Joe Lovano and George Adams, Eddie Harris--and if you're learning jazz saxophone, you'll learn this.

Sonny and Trane are truly heirs presumptive on this recording. I wrote about the seamless weaving together of solos by Coltrane, Donald Byrd and Hank Mobley on the Elmo Hope session of a few weeks earlier. Not so here. These guys are kicking each other, challenging each other, every step of a twelve-minute journey, and the winner...well, the listener, for a start. But also both sax men. They both emerge triumphant. Wikipedia quotes jazz critic Dan Krow as saying that "the two complement each other, and the track does not sound like a competition between the two rising saxophonists," and that's sort of true, in that there are no losers. Turns out they both really are heirs apparent, if not royalty already.

The rest of the session is Rollins and the rhythm section. The music is completely different, but no less rewarding: a thoughtful, delicate jazz impression of a piece by impressionist composer Claude Debussy. Rollins is outstanding on it; so are Garland and Chambers, in their solos. Rodgers and Hart's "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World" is kicked harder, and gives Philly Joe Jones some space to swing, and has a particularly nifty closing statement of the melody by Rollins.

"Paul's Pal" is a Rollins composition, and unsurprisingly enough, gives a showcase to Paul Chambers. But Sonny also shows what a pal he is by playing one part in such a low register that he's nearly down there with the bass. He also proves to be a pretty good pal to Garland and Jones. This is a true quartet session, with everyone getting solo space, and everyone contributing to the whole experience.

Tenor Madness became the title of the album. It's on lots of lists of greatest jazz albums of all time--mostly for the title track, but even without it, the album would rank way up there.

And here, for one track, is the tenor player Miles hired when he couldn't get Sonny. These are two young men who are poised to become the dominant tenor saxophone players in jazz, the heirs apparent to Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster and Lester Young.

I realized, as I wrote that, that I had never been quite sure what "heir apparent" meant, so I looked it up. An heir apparent is the next in line for succession to a throne or a title, and is next in line no matter what. This is distinguished from an heir presumptive, who is next in line until someone comes along with a better claim. So in jazz, one would have to say that all heirs are heirs presumptive--they are one cutting contest away from being displaced as next in line to the throne. For that matter, jazz royalty are kings presumptive.

But these were the two, and time and history have moved them from presumptive to apparent to jazz royalty, and this one track, from this one recording session, is their only appearance on record together. Ever.

The tune is "Tenor Madness," and it has become a jazz standard...and not just for tenor players. On YouTube, you can find amazing renditions of it by Emily Remler and Toots Thielemans. Tenor players who have recorded it include Arnett Cobb and Joe Henderson, Dexter Gordon, Joe Lovano and George Adams, Eddie Harris--and if you're learning jazz saxophone, you'll learn this.

Sonny and Trane are truly heirs presumptive on this recording. I wrote about the seamless weaving together of solos by Coltrane, Donald Byrd and Hank Mobley on the Elmo Hope session of a few weeks earlier. Not so here. These guys are kicking each other, challenging each other, every step of a twelve-minute journey, and the winner...well, the listener, for a start. But also both sax men. They both emerge triumphant. Wikipedia quotes jazz critic Dan Krow as saying that "the two complement each other, and the track does not sound like a competition between the two rising saxophonists," and that's sort of true, in that there are no losers. Turns out they both really are heirs apparent, if not royalty already.

|

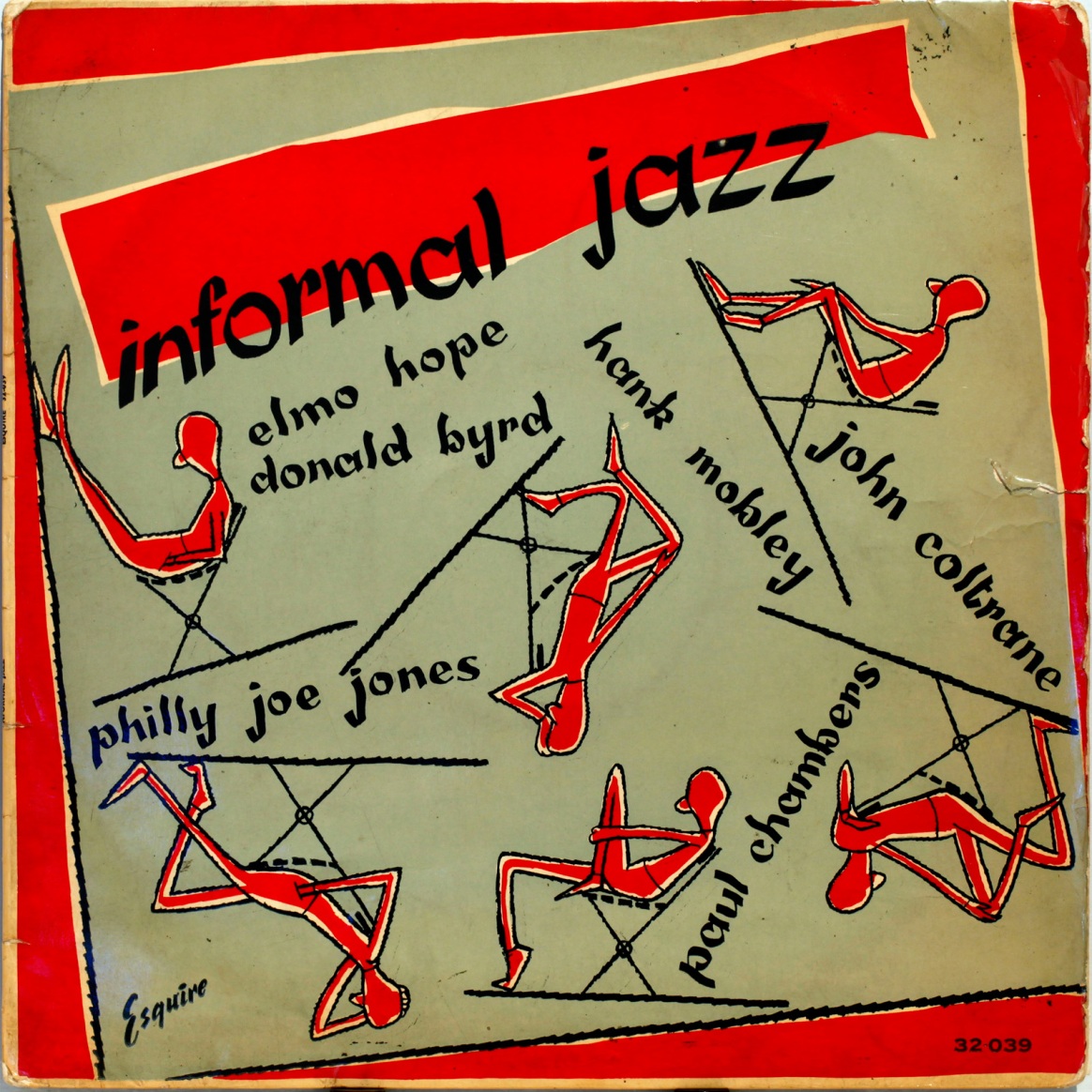

| On the left, the Prestige cover. On the right, the British Esquire label cover, far more imaginative. The cover design is credited to Sherlock, about whom I can find nothing. |

The rest of the session is Rollins and the rhythm section. The music is completely different, but no less rewarding: a thoughtful, delicate jazz impression of a piece by impressionist composer Claude Debussy. Rollins is outstanding on it; so are Garland and Chambers, in their solos. Rodgers and Hart's "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World" is kicked harder, and gives Philly Joe Jones some space to swing, and has a particularly nifty closing statement of the melody by Rollins.

"Paul's Pal" is a Rollins composition, and unsurprisingly enough, gives a showcase to Paul Chambers. But Sonny also shows what a pal he is by playing one part in such a low register that he's nearly down there with the bass. He also proves to be a pretty good pal to Garland and Jones. This is a true quartet session, with everyone getting solo space, and everyone contributing to the whole experience.

Tenor Madness became the title of the album. It's on lots of lists of greatest jazz albums of all time--mostly for the title track, but even without it, the album would rank way up there.

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 1 here.

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

Listening to Prestige Part 171: Miles Davis Quintet

Now we're entering the Miles Davis Contractual Marathon in earnest. His November session was only six songs. This one has thirteen--fourteen if you count the two versions of "The Theme." By way of comparison, three separate recording sessions for Columbia at around the same time period yielded seven tunes.

What's now known as the First Quintet jelled in the fall of 1955, when John Coltrane replaced Sonny Rollins, They appeared on the Steve Allen show in October, did their first studio session for Columbia a week later, and made their first recording for Prestige in November.

So by the time they got together for their first Contractual Marathon, they'd been working together for half a year. How long does it take a group of brilliant jazz musicians to coalesce? Well, we've just listened to the Elmo Hope session with Coltrane, Hank Mobley and Donald Byrd, so we know the answer is that you can just all wander into Rudy's parents' living room on a nice spring day and start playing seamlessly intuitive jazz right off the bat. Of course it helps if you have a great rhythm section, and one was there that day: Elmo Hope, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones.

How much does it help? Jack Maher, in the liner notes to one of the LPs to come out of this session, recalls a club date where Miles and Coltrane were hopelessly out of sync, and the music was almost unlistenable. Maher recalls that, sitting with Teddy Charles, he commented on it. Charles's response:

I don't think he'd ever recorded "Diane" before. It wasn't exactly a jazz standard, and hasn't exactly become one, although Pete and Conte Candoli did a West Coast version a few years later. It was composed by Erno Rapee, primarily a symphonic composer. Its best known recording was by Mario Lanza, and it's not one of Lanza's best numbers. In fact, although it's been widely recorded by vocalists as far-ranging as country singer Jim Reeves, it really doesn't seem like a very good song. Until Miles gets hold of it. And Coltrane, who'd had a lovely solo on the first cut, really steps out and wails here, as he does on "Trane's Blues," which sort of makes its recorded debut here--that is, first recording under this title. It was called "Vierd Blues" when Miles and the same rhythm section, plus Sonny Rollins, recorded it in March, and composer credit was given to Miles. And also in March, it was recorded for a West Coast label by a group under Chambers' name, featuring Coltrane, Jones and Kenny Drew, as "John Paul Jones," for reasons that should be self-explanatory.

Going back and listening to both versions of "In Your Own Sweet Way" again, something occurs to me. Rollins is capable of as much romanticism as Davis is. So is Tommy Flanagan, actually. And Miles holds back a little. In the quintet version, he's matched with John Coltrane, who is following his own muse, which will take him, as we know, into remarkable places. But even here, he's into his own explorations, and this gives Miles license to completely open up to the romantic side of his nature. Listen to the way Miles comes back in at the end "In Your Own Sweet Way," after Coltrane's solo, simplifying, finding all the sweetness in the melody.

And I think this is one of the reasons why the albums that came out of these sessions were so popular at the time, and remain so popular. We've listened to the Davis/Charlie Parker recording session of 1953, where they ran out of studio time, and had to record "Round Midnight" in fifteen minutes. I said of that recording, "No time to be clever, no time to intellectualize it. Just go with the emotions closest to the surface, and for Parker pain was never far below."

Miles doesn't have a lot of time here, and maybe he's taking the most direct route. He's doing what Chuck Berry says modern jazzers don't do: trust the beauty of the melody.

But maybe he's doing it because he knows he can. He's been playing with Coltrane, Garland, Chambers and Jones for six months now, and he trusts them to provide a framework. Maybe that's one of the reasons why he chose so many ballads for this session.

"Something I Dreamed Last Night" is the first of these. It's a Sammy Fain melody that's been done

often by vocalists, starting with Marlene Dietrich, who is never simply romantic. There's always the subtext that she knows more about life than you'll ever know. Sarah Vaughan is surrounded by strings for her version, which makes for romance, but Sarah always has an edge, too. She always sings the song, and does it justice--more than justice--but she's also always singing the music, making a statement about it. Miles does that too, of course, but somehow he stays closer to the emotional purity. Johnny Mathis is all about beauty and emotion, but Mathis, as good as he is, is a bit of a one-trick pony -- beauty and emotion is what he's always going for. For Miles, it's a choice. And that brings a special kind of intensity.

There's probably no one who's never recorded "It Could Happen to You," starting with Dorothy Lamour in a 1944 movie. There's probably no way to sentimentalize a song more than Lamour does, even though she sings it to Fred MacMurray, and Miles finds a drier, more emotionally ambiguous approach, as he does with "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," the Rodgers and Hammerstein paean from Oklahoma to a bucolic life that Miles never knew nor wanted to know. In both of these, he sets up Coltrane for adventurous and bopworthy solos.

He gets back to the achingly beautiful with "It Never Entered My Mind," a song from the other side of the Richard Rodgers songbook, the dark side that Lorenz Hart explored, as opposed to Oscar Hammerstein's sunny side. Hart's lyrics capture the devastating loss of love to a guy who maybe deserved it, but that doesn't make the loss any less painful, especially since he knows he deserves it. Miles gives us the loss, in its purest form. He lets Red Garland explore other emotions, and then he brings it back to the melody, and the simple emotion. "When I Fall in Love," written by Victor Young for a forgettable 1952 movie, is nowhere near as good a song, but Miles finds the pathos in it, and makes the melody better than it perhaps has a right to be. There'll be more ballads in the next and final chapter of the Contractual Marathon, and they'll be beautiful too.

Then there are bebop classics (Dizzy Gillespie's "Woody'n You" and "Salt Peanuts," Miles's "Four"). They're treated like old friends, and they give all the satisfaction of hanging out with old friends...who have something new to say. Philly Joe Jones takes over "Salt Peanuts" and leaves you breathless. There's no chanted "Salt Peanuts! Salt Peanuts!" but Miles's horn gives a pretty good approximation.

Garland, Chambers and Jones are given the spotlight on "Ahmad's Blues," including a gorgeous bowed bass solo by Chambers. They demonstrate what Teddy Charles was talking about, and they demonstrated it to Bob Weinstock too -- he signed them as a trio.

Miles was a huge fan of Ahmad Jamal, and a lot of jazz critics thought Miles was crazy. Jamal played a lot of gigs in Chicago, which automatically put him the Second City second rank, and he mostly played with a trio in cocktail lounge settings, which made it easy to dismiss him as cocktail pianist. It should come as no surprise to find out that Miles was right.

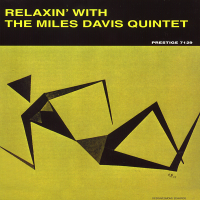

The contractual sessions were cut up and released on four different albums over the next few years. "Woody'n You" and "It Could Happen to You" were on the March 1958 release, Relaxin' with the Miles Davis Quintet (the first release, Cookin' in 1957, was all tunes from the later session).

"In Your Own Sweet Way," "Trane's Blues," "Ahmad's Blues," "It Never Entered My Mind," "Four" and the two versions of "The Theme" came out on the 1959 release, Workin' with the Miles Davis Quintet.

"Diane," "Something I Dreamed Last Night,""Surrey with the Fringe on Top," "When I Fall in Love" and "Salt Peanuts" were all held off until 1961 and the final LP from the 1956 sessions, Steamin' with the Miles Davis Quintet.

A number of these tunes also eventually found their way to 45 RPM singles, as Prestige really entered that game in the 1960s. "It Never Entered My Mind" came out in early 1960, divided onto two sides of a 45, and July of 1960 saw "When I Fall in Love"/"I Could Write a Book." The marketing folks at Prestige had apparently decided that two songs were a better sell than Parts 1 and 2, which meant that These long form LP improvisations were released in edited versions. "When I Fall in Love," at 4:21, could easily have been split in half, but instead it was cut down to 2:25. Same with "I Could Write a Book," which went from 5:11 t0 3:37.

A number of these tunes also eventually found their way to 45 RPM singles, as Prestige really entered that game in the 1960s. "It Never Entered My Mind" came out in early 1960, divided onto two sides of a 45, and July of 1960 saw "When I Fall in Love"/"I Could Write a Book." The marketing folks at Prestige had apparently decided that two songs were a better sell than Parts 1 and 2, which meant that These long form LP improvisations were released in edited versions. "When I Fall in Love," at 4:21, could easily have been split in half, but instead it was cut down to 2:25. Same with "I Could Write a Book," which went from 5:11 t0 3:37.

"Surrey with the Fringe on Top"/"Diane" was released in April or May of 1963, as Prestige continued to space out the contractual sessions as far as they could. Both of these were in severely edited versions -- the originals had been 9:05 and 7:49 respectively. For that matter, on "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," they edited the "e" out of "Surrey."

What's now known as the First Quintet jelled in the fall of 1955, when John Coltrane replaced Sonny Rollins, They appeared on the Steve Allen show in October, did their first studio session for Columbia a week later, and made their first recording for Prestige in November.

So by the time they got together for their first Contractual Marathon, they'd been working together for half a year. How long does it take a group of brilliant jazz musicians to coalesce? Well, we've just listened to the Elmo Hope session with Coltrane, Hank Mobley and Donald Byrd, so we know the answer is that you can just all wander into Rudy's parents' living room on a nice spring day and start playing seamlessly intuitive jazz right off the bat. Of course it helps if you have a great rhythm section, and one was there that day: Elmo Hope, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones.

How much does it help? Jack Maher, in the liner notes to one of the LPs to come out of this session, recalls a club date where Miles and Coltrane were hopelessly out of sync, and the music was almost unlistenable. Maher recalls that, sitting with Teddy Charles, he commented on it. Charles's response:

If it doesn't take long for a bunch of great jazz musicians to find a groove, it takes a little longer to simply know this many tunes in common. And that's where six months of club dates starts to matter. Most, if not all of the songs played on this and the following marathon session were ones that the group had played on the road, in clubs. A bunch of them were pieces that Miles had recorded before, including the one they started the session with, "In Your Own Sweet Way," which he had just done two months earlier in an abbreviated session with a quintet featuring Sonny Rollins. This version is maybe better -- starting right off with Miles and his Harmon mute, setting a tone for the whole session."Watch the rhythm section. This is the best rhythm section in jazz the hardest swinging rhythm section, watch out when they loosen up."At this point Miles and Coltrane abruptly walked off the stand. This was the usual cue for Red Garland to his featured number-trio style. Miles did this regularly when he was bored, felt he needed a break or a beer. I don't remember what tune it was exactly, something like "Ahmad's Blues" in this album, if I'm not mistaken, a medium tempo that more or less plays itself.From the beginning the three men relaxed. Alone on the stand Red, Paul and Philly Joe relaxed and fell into a smooth spirited swing. The trio drew more applause for that one tune than the whole group had for the entire evening. When Miles and Coltrane returned to the bandstand the atmosphere in the club had changed. Somehow the tension had gone, and, on the next tune, "It Never Entered My Mind", which is also performed in this album, Miles played one of the most beautiful choruses I've ever heard him play.

I don't think he'd ever recorded "Diane" before. It wasn't exactly a jazz standard, and hasn't exactly become one, although Pete and Conte Candoli did a West Coast version a few years later. It was composed by Erno Rapee, primarily a symphonic composer. Its best known recording was by Mario Lanza, and it's not one of Lanza's best numbers. In fact, although it's been widely recorded by vocalists as far-ranging as country singer Jim Reeves, it really doesn't seem like a very good song. Until Miles gets hold of it. And Coltrane, who'd had a lovely solo on the first cut, really steps out and wails here, as he does on "Trane's Blues," which sort of makes its recorded debut here--that is, first recording under this title. It was called "Vierd Blues" when Miles and the same rhythm section, plus Sonny Rollins, recorded it in March, and composer credit was given to Miles. And also in March, it was recorded for a West Coast label by a group under Chambers' name, featuring Coltrane, Jones and Kenny Drew, as "John Paul Jones," for reasons that should be self-explanatory.

Going back and listening to both versions of "In Your Own Sweet Way" again, something occurs to me. Rollins is capable of as much romanticism as Davis is. So is Tommy Flanagan, actually. And Miles holds back a little. In the quintet version, he's matched with John Coltrane, who is following his own muse, which will take him, as we know, into remarkable places. But even here, he's into his own explorations, and this gives Miles license to completely open up to the romantic side of his nature. Listen to the way Miles comes back in at the end "In Your Own Sweet Way," after Coltrane's solo, simplifying, finding all the sweetness in the melody.

And I think this is one of the reasons why the albums that came out of these sessions were so popular at the time, and remain so popular. We've listened to the Davis/Charlie Parker recording session of 1953, where they ran out of studio time, and had to record "Round Midnight" in fifteen minutes. I said of that recording, "No time to be clever, no time to intellectualize it. Just go with the emotions closest to the surface, and for Parker pain was never far below."

Miles doesn't have a lot of time here, and maybe he's taking the most direct route. He's doing what Chuck Berry says modern jazzers don't do: trust the beauty of the melody.

But maybe he's doing it because he knows he can. He's been playing with Coltrane, Garland, Chambers and Jones for six months now, and he trusts them to provide a framework. Maybe that's one of the reasons why he chose so many ballads for this session.

"Something I Dreamed Last Night" is the first of these. It's a Sammy Fain melody that's been done

often by vocalists, starting with Marlene Dietrich, who is never simply romantic. There's always the subtext that she knows more about life than you'll ever know. Sarah Vaughan is surrounded by strings for her version, which makes for romance, but Sarah always has an edge, too. She always sings the song, and does it justice--more than justice--but she's also always singing the music, making a statement about it. Miles does that too, of course, but somehow he stays closer to the emotional purity. Johnny Mathis is all about beauty and emotion, but Mathis, as good as he is, is a bit of a one-trick pony -- beauty and emotion is what he's always going for. For Miles, it's a choice. And that brings a special kind of intensity.

There's probably no one who's never recorded "It Could Happen to You," starting with Dorothy Lamour in a 1944 movie. There's probably no way to sentimentalize a song more than Lamour does, even though she sings it to Fred MacMurray, and Miles finds a drier, more emotionally ambiguous approach, as he does with "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," the Rodgers and Hammerstein paean from Oklahoma to a bucolic life that Miles never knew nor wanted to know. In both of these, he sets up Coltrane for adventurous and bopworthy solos.

He gets back to the achingly beautiful with "It Never Entered My Mind," a song from the other side of the Richard Rodgers songbook, the dark side that Lorenz Hart explored, as opposed to Oscar Hammerstein's sunny side. Hart's lyrics capture the devastating loss of love to a guy who maybe deserved it, but that doesn't make the loss any less painful, especially since he knows he deserves it. Miles gives us the loss, in its purest form. He lets Red Garland explore other emotions, and then he brings it back to the melody, and the simple emotion. "When I Fall in Love," written by Victor Young for a forgettable 1952 movie, is nowhere near as good a song, but Miles finds the pathos in it, and makes the melody better than it perhaps has a right to be. There'll be more ballads in the next and final chapter of the Contractual Marathon, and they'll be beautiful too.

Then there are bebop classics (Dizzy Gillespie's "Woody'n You" and "Salt Peanuts," Miles's "Four"). They're treated like old friends, and they give all the satisfaction of hanging out with old friends...who have something new to say. Philly Joe Jones takes over "Salt Peanuts" and leaves you breathless. There's no chanted "Salt Peanuts! Salt Peanuts!" but Miles's horn gives a pretty good approximation.

Garland, Chambers and Jones are given the spotlight on "Ahmad's Blues," including a gorgeous bowed bass solo by Chambers. They demonstrate what Teddy Charles was talking about, and they demonstrated it to Bob Weinstock too -- he signed them as a trio.

Miles was a huge fan of Ahmad Jamal, and a lot of jazz critics thought Miles was crazy. Jamal played a lot of gigs in Chicago, which automatically put him the Second City second rank, and he mostly played with a trio in cocktail lounge settings, which made it easy to dismiss him as cocktail pianist. It should come as no surprise to find out that Miles was right.

The contractual sessions were cut up and released on four different albums over the next few years. "Woody'n You" and "It Could Happen to You" were on the March 1958 release, Relaxin' with the Miles Davis Quintet (the first release, Cookin' in 1957, was all tunes from the later session).

"In Your Own Sweet Way," "Trane's Blues," "Ahmad's Blues," "It Never Entered My Mind," "Four" and the two versions of "The Theme" came out on the 1959 release, Workin' with the Miles Davis Quintet.

"Diane," "Something I Dreamed Last Night,""Surrey with the Fringe on Top," "When I Fall in Love" and "Salt Peanuts" were all held off until 1961 and the final LP from the 1956 sessions, Steamin' with the Miles Davis Quintet.

A number of these tunes also eventually found their way to 45 RPM singles, as Prestige really entered that game in the 1960s. "It Never Entered My Mind" came out in early 1960, divided onto two sides of a 45, and July of 1960 saw "When I Fall in Love"/"I Could Write a Book." The marketing folks at Prestige had apparently decided that two songs were a better sell than Parts 1 and 2, which meant that These long form LP improvisations were released in edited versions. "When I Fall in Love," at 4:21, could easily have been split in half, but instead it was cut down to 2:25. Same with "I Could Write a Book," which went from 5:11 t0 3:37.

A number of these tunes also eventually found their way to 45 RPM singles, as Prestige really entered that game in the 1960s. "It Never Entered My Mind" came out in early 1960, divided onto two sides of a 45, and July of 1960 saw "When I Fall in Love"/"I Could Write a Book." The marketing folks at Prestige had apparently decided that two songs were a better sell than Parts 1 and 2, which meant that These long form LP improvisations were released in edited versions. "When I Fall in Love," at 4:21, could easily have been split in half, but instead it was cut down to 2:25. Same with "I Could Write a Book," which went from 5:11 t0 3:37."Surrey with the Fringe on Top"/"Diane" was released in April or May of 1963, as Prestige continued to space out the contractual sessions as far as they could. Both of these were in severely edited versions -- the originals had been 9:05 and 7:49 respectively. For that matter, on "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," they edited the "e" out of "Surrey."

Wednesday, February 10, 2016

Listening to Prestige Part 170: Elmo Hope All-Star Sextet

Elmo Hope's star, never as bright as it should have been, was perhaps beginning to wane at this point. The session is listed as "Elmo Hope All-Star Sextet," and the album was released as by the Elmo Hope Sextet, but at exactly the same time, so it would seem, it was also released as by Hank Mobley and John Coltrane, as Prestige PRLP 7043 and 7043 (alt).

And Ira Gitler, in his liner notes, describes the session as being "the nominal leader on the date," whatever that means. Gitler also suggests, without actually saying it, that the session is a buncha guys who happened to drop in at Rudy's parents' living room on a Friday afternoon to see what was happening.

If so. that would make this just about the perfect Bob Weinstock jam session, and maybe Gitler is exaggerating the casualness of the ensemble a little bit, but maybe not. I'm willing to take it as mostly true, and I'm willing to credit it as a quintessential tribute to the Weinstock philosophy of what jazz is.

As Gitler goes on to point, out, these musicians were hardly strangers to each other. Donald Byrd and Hank Mobley had played together in the Jazz Messengers; John Coltrane, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones were the nucleus of the new Miles Davis Quintet, and Jones and Hope went even farther back.

As Gitler goes on to point, out, these musicians were hardly strangers to each other. Donald Byrd and Hank Mobley had played together in the Jazz Messengers; John Coltrane, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones were the nucleus of the new Miles Davis Quintet, and Jones and Hope went even farther back.

It's interesting to note how strong the rhythm and blues roots were for these musicians. Jones and Hope had first played together in Joe Morris's band, Hank Mobley with Paul Gayten, John Coltrane with Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson. Also interesting that when they get together for a casual jam session, they go to bebop, not rhythm and blues, as a lingua franca.

Even more interesting, to me, is how powerful a lingua franca this is. Gitler, in his liner notes, lists the order of solos, as he oftenh does, and I wonder if he got, or gets, enough credit for this service. Too many serious jazz aficionados are also jazz snobs, and would dismiss this as pablum, but for the rest of us, it's very useful in following a jazz recording. In this case, Gitler gives us a remarkably involved and complex series of solos:

The other is--it's almost beyond understanding how completely these loose, informal jammers are on the same page. Very often, especially in the early days of bebop, when the music was shifting from dance-centric to listener-centric, and the idea of a virtuoso solo was moved to the forefront, a soloist would finish off his turn with a little statement -- "Here, what are you going to do with that?" -- and there'd be a vamp by the piano or bass (not so often bass when recording engineers couldn't pick him us as well), for the listener and the next soloist to reflect on what had just been heard. Not so here. This music is seamless, so much so that you sometimes even forget to notice whether you're listening to Byrd or Coltrane -- and that's not leaving out of account that we're listening to some of the most distinctive voices in jazz.

Two of the pieces are Elmo Hope compositions -- "riffers which expedite the blowing," in Gitler's words, but they're more than that. Both, especially the bluesy "On It," are lyrical. Hope was a gifted composers, and these two tunes justify this being labeled as an Elmo Hope sessions.

The other two are standards, very much "mainly vehicles for blowing," in that like the two Hope tunes, they give the soloists the basis for work which is so seamless it almost makes a succession of solos sound like an ensemble. "Polka Dots and Moonbeams" was a Jimmy Van Heusen pop hit for Tommy Dorsey/Sinatra which has become a favorite of the moderns, with versions by Bud Powell, Chet Baker, Bill Evans, Wes Montgomery, Blue Mitchell...it has been listed as one of the most frequently recorded jazz standards.

I've commented before on how many times beboppers have reached back to a very early age, taking songs from operetta to transform into a modern idiom. "Avalon," in a way, harkens back even farther. It's credited to Al Jolson, Buddy deSylva and Vincent Rose, and while it's questionable whether Jolson really did any of the writing, it's also sort of questionable whether Rose did. The melody is close enough to an aria from Tosca that the Puccini estate was able to sue for plagiarism and win.

Are there any other modern jazz versions of operatic arias (not counting Porgy and Bess)? Probably. There must be some from Carmen. But I can't think of any offhand.

A couple of digressions before I let you go. A lot of the Prestige catalog was licensed in England to the Esquire label. The Esquire release of this album, which must have been not long after the Prestige release, has cover art by Ralph Steadman. Steadman is one of the great illustrators of our era, and I suspect he may be pretty embarrassed by this, which doesn't begin to suggest Alice in Wonderland or Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. He must have still been an art student at this time, and nowhere in his biography does it mention any work as an illustrator for record labels.

Second digression. And I know I'm preaching to the choir here. Everyone who cares about music, or cares about education, knows how important music education is. Donald Byrd went to Cass Technical High School in Detroit. We think of Detroit today as the epicenter of urban blight and hopelessness, but Cass Tech has held onto its music ed program, and according to its Wiki page, "Cass Tech students' strong academic performances draw recruiters from across the country, including Ivy League representatives eager to attract the top minority applicants."

Because Cass Tech continues to have a music education program, its graduates have made their mark from swing to hip-hop, not to mention opera and gospel. I promise I won't keep posting lists like this, but here are some of Cass Tech's graduates, and of course I'm not including the kids who went on to become teachers, or the kids who simply stayed in school because there was a band and a concert choir.

This session was released simultaneously under Hope's name as Informal Jazz, and under Coltrane's and Mobley's names as Two Tenors. Later, as Coltrane became the big star, it was reissued under his name as Two Tenors with Hank Mobley.

.

And Ira Gitler, in his liner notes, describes the session as being "the nominal leader on the date," whatever that means. Gitler also suggests, without actually saying it, that the session is a buncha guys who happened to drop in at Rudy's parents' living room on a Friday afternoon to see what was happening.

If so. that would make this just about the perfect Bob Weinstock jam session, and maybe Gitler is exaggerating the casualness of the ensemble a little bit, but maybe not. I'm willing to take it as mostly true, and I'm willing to credit it as a quintessential tribute to the Weinstock philosophy of what jazz is.

As Gitler goes on to point, out, these musicians were hardly strangers to each other. Donald Byrd and Hank Mobley had played together in the Jazz Messengers; John Coltrane, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones were the nucleus of the new Miles Davis Quintet, and Jones and Hope went even farther back.

As Gitler goes on to point, out, these musicians were hardly strangers to each other. Donald Byrd and Hank Mobley had played together in the Jazz Messengers; John Coltrane, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones were the nucleus of the new Miles Davis Quintet, and Jones and Hope went even farther back.It's interesting to note how strong the rhythm and blues roots were for these musicians. Jones and Hope had first played together in Joe Morris's band, Hank Mobley with Paul Gayten, John Coltrane with Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson. Also interesting that when they get together for a casual jam session, they go to bebop, not rhythm and blues, as a lingua franca.

Even more interesting, to me, is how powerful a lingua franca this is. Gitler, in his liner notes, lists the order of solos, as he oftenh does, and I wonder if he got, or gets, enough credit for this service. Too many serious jazz aficionados are also jazz snobs, and would dismiss this as pablum, but for the rest of us, it's very useful in following a jazz recording. In this case, Gitler gives us a remarkably involved and complex series of solos:

Weejah: Opening riff, Hank, Donald, Trane (bridge), Hank, Donald (4), Hank (2), Trane (2), Hank (1), Trane (1), Hank (1), Trane (1), Elmo (3), Chambers (2), Donald, Hank, Trane in fours with Joe (1), Joe (1), out chorus in same order as opener.And even with Ira's help, I get lost. Well, I did recognize when Elmo came in. Or:

On it: Donald (8), Elmo (8), Hank (3), Trane (3), then two choruses each, followed by one chorus each, followed by two choruses of fours, two of twos, and another of fours. Hank is first at the beginning of the conversations.This is a good thing to keep in mind the next time I'm tempted to criticize Gitler as a commentator on jazz. Yeah, I got lost again here. But there are a couple of reasons. One is, at a certain point I have to give up feeling the pressure -- am I going to be able to tell where they go from trading fours to trading twos? -- and just listen to the music.

The other is--it's almost beyond understanding how completely these loose, informal jammers are on the same page. Very often, especially in the early days of bebop, when the music was shifting from dance-centric to listener-centric, and the idea of a virtuoso solo was moved to the forefront, a soloist would finish off his turn with a little statement -- "Here, what are you going to do with that?" -- and there'd be a vamp by the piano or bass (not so often bass when recording engineers couldn't pick him us as well), for the listener and the next soloist to reflect on what had just been heard. Not so here. This music is seamless, so much so that you sometimes even forget to notice whether you're listening to Byrd or Coltrane -- and that's not leaving out of account that we're listening to some of the most distinctive voices in jazz.

Two of the pieces are Elmo Hope compositions -- "riffers which expedite the blowing," in Gitler's words, but they're more than that. Both, especially the bluesy "On It," are lyrical. Hope was a gifted composers, and these two tunes justify this being labeled as an Elmo Hope sessions.

The other two are standards, very much "mainly vehicles for blowing," in that like the two Hope tunes, they give the soloists the basis for work which is so seamless it almost makes a succession of solos sound like an ensemble. "Polka Dots and Moonbeams" was a Jimmy Van Heusen pop hit for Tommy Dorsey/Sinatra which has become a favorite of the moderns, with versions by Bud Powell, Chet Baker, Bill Evans, Wes Montgomery, Blue Mitchell...it has been listed as one of the most frequently recorded jazz standards.

I've commented before on how many times beboppers have reached back to a very early age, taking songs from operetta to transform into a modern idiom. "Avalon," in a way, harkens back even farther. It's credited to Al Jolson, Buddy deSylva and Vincent Rose, and while it's questionable whether Jolson really did any of the writing, it's also sort of questionable whether Rose did. The melody is close enough to an aria from Tosca that the Puccini estate was able to sue for plagiarism and win.

Are there any other modern jazz versions of operatic arias (not counting Porgy and Bess)? Probably. There must be some from Carmen. But I can't think of any offhand.

A couple of digressions before I let you go. A lot of the Prestige catalog was licensed in England to the Esquire label. The Esquire release of this album, which must have been not long after the Prestige release, has cover art by Ralph Steadman. Steadman is one of the great illustrators of our era, and I suspect he may be pretty embarrassed by this, which doesn't begin to suggest Alice in Wonderland or Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. He must have still been an art student at this time, and nowhere in his biography does it mention any work as an illustrator for record labels.

Second digression. And I know I'm preaching to the choir here. Everyone who cares about music, or cares about education, knows how important music education is. Donald Byrd went to Cass Technical High School in Detroit. We think of Detroit today as the epicenter of urban blight and hopelessness, but Cass Tech has held onto its music ed program, and according to its Wiki page, "Cass Tech students' strong academic performances draw recruiters from across the country, including Ivy League representatives eager to attract the top minority applicants."

Because Cass Tech continues to have a music education program, its graduates have made their mark from swing to hip-hop, not to mention opera and gospel. I promise I won't keep posting lists like this, but here are some of Cass Tech's graduates, and of course I'm not including the kids who went on to become teachers, or the kids who simply stayed in school because there was a band and a concert choir.

- Dorothy Ashby, jazz harpist and composer.

- Geri Allen, post bop jazz pianist.

- Sean Anderson aka Big Sean; hip-hop artist signed to Kanye West's Label (G.O.O.D. Music).

- Kenny Burrell, jazz guitarist.

- Ellen Burstyn, won Academy Award for Best Actress for Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore and starred in The Exorcist, Tony Award winner, Emmy Award winner, Golden Globe Award winner (did not graduate).

- Donald Byrd, jazz and rhythm-and-blues trumpeter.

- Regina Carter, jazz violinist.

- Ron Carter, jazz double-bassist.

- Doug Watkins, jazz bassist.

- Paul Chambers, jazz bassist.

- Alice Coltrane, jazz pianist, organist, harpist, composer, and the wife of John Coltrane.

- Muriel Costa-Greenspon, mezzo-soprano who had a lengthy career at the New York City Opera between 1963 and 1993.

- Jerald Daemyon, electric jazz violinist, composer and producer known for bringing technical refinement to violin improvisation.

- Delores Ivory Davis, was internationally recognized in opera, oratorio, and for performances with Springfield (Mass.) Symphony, St. Paul Symphony, and Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

- Carole Gist, 1990 Miss USA, first African American woman to win the Miss USA title.

- Wardell Gray, jazz tenor saxophonist who straddled the swing and bebop periods.

- David Alan Grier, actor, comedian.

- J. C. Heard,[36] swing, bop, and blues drummer.

- Major Holley, jazz upright bassist.

- Ali Jackson, jazz drummer.

- Philip Johnson actor, leading role in the Lifetime movie America.

- Ella Joyce, actress.

- Hugh Lawson,[36] was one of many talented Detroit jazz pianists of the 1950s

- Donyale Luna, model and actress.

- Howard McGhee, one of the first bebop jazz trumpeters, together with Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro and Idrees Sulieman.

- Al McKibbon,[36] jazz double bassist, known for his work in bop, hard bop, and Latin jazz.

- Billy Mitchell,[36] jazz tenor saxophonist best known for his work with Woody Herman when he replaced Gene Ammons in his band.

- Kenya Moore, 1993 Miss USA.

- Naima Mora, fashion model, America's Next Top Model winner (Season 4).

- J. Moss (aka James Moss), Grammy Award-winning gospel singer-songwriter, composer, arranger, and record producer.

- Greg Phillinganes, (1974) session keyboardist.

- Della Reese, singer, actress, later famous for playing Tess on the television show Touched by an Angel

- Frank Rosolino,[37] was an American jazz trombonist.

- Diana Ross (1962), singer, actress, graduated one full semester ahead of her classmates; major listed in Cass Tech Triangle Yearbook was "home economics"; studied costume design as her curriculum path; 2007 Kennedy Center Honors recipient.

- Donald Sinta, classical saxophonist, educator, and administrator; in 1969 he was the first elected chair of the World Saxophone Congress.

- Cornelius Smith Jr., actor, 2010 NAACP Image Award winner for Outstanding Actor in a Daytime Drama Series.

- Lucky Thompson,[36] jazz tenor and soprano saxophonist.

- Lily Tomlin, comedian, actress, 2014 Kennedy Center Honors recipient; winner of two Tony Awards, a Grammy Award, 5 Emmy Awards and a Daytime Emmy Award. Listed and pictured in the Yearbook as Mary Jane Tomlin – a cheerleader.

- Jack White, acclaimed musician and member of The White Stripes, The Raconteurs, and The Dead Weather.[38]

- Gerald Wilson, influential jazz trumpeter, Big Band leader and composer.

This session was released simultaneously under Hope's name as Informal Jazz, and under Coltrane's and Mobley's names as Two Tenors. Later, as Coltrane became the big star, it was reissued under his name as Two Tenors with Hank Mobley.

.

Saturday, February 06, 2016

Listening to Prestige Part 169: Gene Ammons

What does a producer of jazz records do? Probably, at best, not all that much. Bob Weinstock recalls that he and Miles Davis would sit down and kick around names -- who's in town, who would you like to record with? -- and that may have been the most of it. Weinstock had his jam session philosophy -- no rehearsal, just get 'em together and let 'em play -- and even so, Miles complained later that he (and every other producer Miles worked with) interfered too much.

So what about this session? Gene Ammons was one of Prestige's stalwarts, going back to the early days, often paired with Sonny Stitt, just as often without, generally preferring the fuller sound of a larger-than-quintet group. For a while he worked with a more or less steady group. almost always including trumpeter Bill Massey. By 1955, he had begun branching out. His three 1955 sessions for Prestige saw almost a complete turnover from session to session (Art and Addison Farmer were on one of them).

Why? Ammons had trouble keeping a group together? Seems unlikely. With his warm touch on ballads, earthy touch on blues, ability to wail with the best of the R&B saxmen, Ammons was one of the most popular jazz artists of the day.

Or perhaps, as he had done with Miles, Bob Weinstock sat down with him and said, "Hey, Gene, let's start mixing it up some. Look how well it worked with Miles. We'll kick around some names, get a bunch of guys together in the studio, see what happens."

So maybe that's what a producer of jazz records does. And how much careful thought and planning went into choosing that bunch of guys? I'd like to think very little. Art and Addison Farmer were around -- they'd just played the Bennie Green session a week or so earlier. The others were inspired choices, but none of them would have required a lot of thought.

What about Candido? Did Bob Weinstock and Ira Gitler sit up all night, saying "We've got to find something new for the next Ammons recording. How about a French horn, like the Miles Davis nonet? Bring Earl Coleman back for some vocals? Or a pianoless group like Gerry Mulligan? Wait! I've got it! We'll bring in some Latin percussion!" Or did Candido just happen to drop by the office that day, and say "Hola - I'm looking for a gig. Got anything?"

I like to think it was the latter.

And Duke Jordan? He was certainly doing a lot of session work in the 50s, not all that much of it with Prestige. He'd played with Art and Addison on a Farmer/Gryce session the previous fall. But for whatever reason they chose him, it was an inspired choice. It goes without saying that with Candido on board, you're going to have some hot rhythms, but it's Jordan whom I keep hearing driving this session. He turns out to be the real inspired choice.

Jordan had also recently written what was to become his most famous composition, "Jor-du," and one certainly wouldn't be surprised to hear it on a date where he was playing, but not so on this one.

Which raises another "what does a producer do?" question. Who chooses the tunes that will go into a recording session, and what's behind that? Obviously, there's a few extra bucks for the composer, and especially for the publishing rights, but there weren't all that many bucks in jazz overall, in those days. Jackie McLean seems almost certainly to be the composer of "Dig," for which Miles Davis took the credit, but when McLean looked into suing over it, he was told not to bother -- even if he won, there wouldn't be any money in it.

Still, you had a couple of excellent composers on this date (in addition to Jordan) and it's no surprise that they're represented--McLean with "Madhouse," Art Farmer with "The Happy Blues."

It's also not surprising that a standard was included. Ammons was great on ballads, and Weinstock liked standards, and although not much jazz was being released on single records any more by 1956, Ammons was still a jukebox favorite. Why "Can't We Be Friends" in particular? Why not? It's a beautiful song.

The one that really interests me is "The Great Lie," a swing era song by Andy Gibson -- credited to Gibson and Cab Calloway. Perhaps there were lyrics by Calloway? I could not find a version of it that included a vocal, but I did find a reference to it in a list of WWII-era songs by Calloway that had social commentary.

Andy Gibson was an underrated composer, whose best known work is probably his brilliant rhythm-and-bluesification of Charlie Parker's "Now's the Time" -- "The Hucklebuck."

It's certainly not unusual for a big band tune to be picked up and adapted by moderns, but I decided to see how this one mutated with different versions, so I listened to four: Cab Calloway (without vocal), Charlie Barnet, Gene Ammons, and Chet Baker/Art Pepper.

I liked Calloway's version, but loved Barnet's. And it brought home to me just how much big band music was an arranger's medium. I don't know who the arranger was for this version of "The Great Lie" -- it could have been Gibson, who worked a lot with Barnet. But it's wonderful, with the shifting horn patterns and solos that weave in and out of them. Charlie Barnet, like Artie Shaw, was heir to millions, and like Shaw, he got out of the music business at a fairly young age, and is probably underrated. Certainly he was by me -- I had listened to "Cherokee," maybe nothing else. This is a terrific band, and a terrific number.

Like Woody Herman, Barnet was open to the influences of bebop, and his later bands had some of the finest modern jazz musicians. But as we move seriously into the bebop-hard bop era, you can hear, listening to Barnet and then Ammons, how much the emphasis has shifted to the soloists. Both versions are hard-swinging, and they share a lot more in common than you'd think. The swing band is fresh and innovative, the bop ensemble is melodic. With all those great soloists, the Ammons band extends the tune a lot longer than Barnet's traditional song, 78 RPM length. Ammons goes nearly nine minutes, and everyone gets solo space, and makes the most of it.

With Baker and Pepper, it's pretty much all solos, and it's cool, and mellow, and all the things you expect from West Coast jazz, and also quite cerebral, but they don't forget to swing, either. And just as I found myself caught up by Duke Jordan's contribution to the Ammons group, I found myself listening to Leroy Vinnegar here, who really propels the swing of the two cool soloists with his bass.

"Madhouse" is the Jackie McLean composition, and it's also the one where Candido really shines.

It's also the one that ended up on the jukeboxes. If Weinstock had thought about using the ballad, he would have had to think again, when the boys stretched it out to over 12 minutes. Of course, "The Happy Blues," which did become the single (as Parts 1 and 2) was also over 12 minutes, but maybe it was easier to edit down. It was also the title track for the LP.

So what about this session? Gene Ammons was one of Prestige's stalwarts, going back to the early days, often paired with Sonny Stitt, just as often without, generally preferring the fuller sound of a larger-than-quintet group. For a while he worked with a more or less steady group. almost always including trumpeter Bill Massey. By 1955, he had begun branching out. His three 1955 sessions for Prestige saw almost a complete turnover from session to session (Art and Addison Farmer were on one of them).

Why? Ammons had trouble keeping a group together? Seems unlikely. With his warm touch on ballads, earthy touch on blues, ability to wail with the best of the R&B saxmen, Ammons was one of the most popular jazz artists of the day.

Or perhaps, as he had done with Miles, Bob Weinstock sat down with him and said, "Hey, Gene, let's start mixing it up some. Look how well it worked with Miles. We'll kick around some names, get a bunch of guys together in the studio, see what happens."

So maybe that's what a producer of jazz records does. And how much careful thought and planning went into choosing that bunch of guys? I'd like to think very little. Art and Addison Farmer were around -- they'd just played the Bennie Green session a week or so earlier. The others were inspired choices, but none of them would have required a lot of thought.

What about Candido? Did Bob Weinstock and Ira Gitler sit up all night, saying "We've got to find something new for the next Ammons recording. How about a French horn, like the Miles Davis nonet? Bring Earl Coleman back for some vocals? Or a pianoless group like Gerry Mulligan? Wait! I've got it! We'll bring in some Latin percussion!" Or did Candido just happen to drop by the office that day, and say "Hola - I'm looking for a gig. Got anything?"

I like to think it was the latter.

And Duke Jordan? He was certainly doing a lot of session work in the 50s, not all that much of it with Prestige. He'd played with Art and Addison on a Farmer/Gryce session the previous fall. But for whatever reason they chose him, it was an inspired choice. It goes without saying that with Candido on board, you're going to have some hot rhythms, but it's Jordan whom I keep hearing driving this session. He turns out to be the real inspired choice.

Jordan had also recently written what was to become his most famous composition, "Jor-du," and one certainly wouldn't be surprised to hear it on a date where he was playing, but not so on this one.

Which raises another "what does a producer do?" question. Who chooses the tunes that will go into a recording session, and what's behind that? Obviously, there's a few extra bucks for the composer, and especially for the publishing rights, but there weren't all that many bucks in jazz overall, in those days. Jackie McLean seems almost certainly to be the composer of "Dig," for which Miles Davis took the credit, but when McLean looked into suing over it, he was told not to bother -- even if he won, there wouldn't be any money in it.

Still, you had a couple of excellent composers on this date (in addition to Jordan) and it's no surprise that they're represented--McLean with "Madhouse," Art Farmer with "The Happy Blues."

It's also not surprising that a standard was included. Ammons was great on ballads, and Weinstock liked standards, and although not much jazz was being released on single records any more by 1956, Ammons was still a jukebox favorite. Why "Can't We Be Friends" in particular? Why not? It's a beautiful song.

The one that really interests me is "The Great Lie," a swing era song by Andy Gibson -- credited to Gibson and Cab Calloway. Perhaps there were lyrics by Calloway? I could not find a version of it that included a vocal, but I did find a reference to it in a list of WWII-era songs by Calloway that had social commentary.

Andy Gibson was an underrated composer, whose best known work is probably his brilliant rhythm-and-bluesification of Charlie Parker's "Now's the Time" -- "The Hucklebuck."

It's certainly not unusual for a big band tune to be picked up and adapted by moderns, but I decided to see how this one mutated with different versions, so I listened to four: Cab Calloway (without vocal), Charlie Barnet, Gene Ammons, and Chet Baker/Art Pepper.

I liked Calloway's version, but loved Barnet's. And it brought home to me just how much big band music was an arranger's medium. I don't know who the arranger was for this version of "The Great Lie" -- it could have been Gibson, who worked a lot with Barnet. But it's wonderful, with the shifting horn patterns and solos that weave in and out of them. Charlie Barnet, like Artie Shaw, was heir to millions, and like Shaw, he got out of the music business at a fairly young age, and is probably underrated. Certainly he was by me -- I had listened to "Cherokee," maybe nothing else. This is a terrific band, and a terrific number.

Like Woody Herman, Barnet was open to the influences of bebop, and his later bands had some of the finest modern jazz musicians. But as we move seriously into the bebop-hard bop era, you can hear, listening to Barnet and then Ammons, how much the emphasis has shifted to the soloists. Both versions are hard-swinging, and they share a lot more in common than you'd think. The swing band is fresh and innovative, the bop ensemble is melodic. With all those great soloists, the Ammons band extends the tune a lot longer than Barnet's traditional song, 78 RPM length. Ammons goes nearly nine minutes, and everyone gets solo space, and makes the most of it.

With Baker and Pepper, it's pretty much all solos, and it's cool, and mellow, and all the things you expect from West Coast jazz, and also quite cerebral, but they don't forget to swing, either. And just as I found myself caught up by Duke Jordan's contribution to the Ammons group, I found myself listening to Leroy Vinnegar here, who really propels the swing of the two cool soloists with his bass.

"Madhouse" is the Jackie McLean composition, and it's also the one where Candido really shines.

It's also the one that ended up on the jukeboxes. If Weinstock had thought about using the ballad, he would have had to think again, when the boys stretched it out to over 12 minutes. Of course, "The Happy Blues," which did become the single (as Parts 1 and 2) was also over 12 minutes, but maybe it was easier to edit down. It was also the title track for the LP.

Labels:

1956 recordings,

Addison Farmer,

Art Farmer,

Art Pepper,

Art Taylor,

Bob Weinstock,

Candido,

Charlie Barnet,

chet baker,

Duke Jordan,

Gene Ammons,

Jackie McLean,

Leroy Vinnegar,

Prestige Records

Wednesday, February 03, 2016

Listening to Prestige Part 168: Bennie Green

Let's start with the music. Bennie Green and Art Farmer have an affinity for each other that keeps on giving.

I talked about sentimentality in my last post, and defended its place in art, but you can also ignore it altogether. Green and Farmer take "My Blue Heaven" at a bebopper's pace, using the melody as a springboard for great improvisation, pretty much forgetting about Molly and me and the baby, although there's a real sweetness to Farmer's restatement of the melody at the end. And although there aren't any blues in that cozy place with the fireplace, these guys find room for them in their improv.

"Cliff Dweller " is a composition by piano player Cliff Smalls, and it kicks off with some very

complex but driving interplay between Smalls, Addison Farmer and Philly Joe Jones. Smalls worked often with Bennie Green, and there may have been an extra affinity there because Smalls was also a trombonist. Further, they shared a taste for the accessibility of rhythm and blues -- Smalls would go on to be the bandleader for Clyde McPhatter, Smokey Robinson, and Brook Benton.

"Let's Stretch" seems to come with no composer credit, so we'll take it as a collectively improvised Five O'clock Blues, and stretch they do, for a well-spent ten-plus minutes.

They finish the set with a nice moody version of "Gone With the Wind."

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(96)/discogs-images/R-4324011-1361742350-2365.jpeg.jpg) Now, moving on to the digression. Jazz.com's online encyclopedia gives this biographical note:

Now, moving on to the digression. Jazz.com's online encyclopedia gives this biographical note:

At a time when music education is disappearing from our test-obsessed schools, it's good to stop and remember how important it was to the American Century in music, our great contribution to world culture. People talk about musicians, particularly soul musicians, and how they learned their music in church, but there were far more who learned in school.

And what about DuSable High? Who started their music careers there?

Holy smoke.

Here's a list from Wikipedia:

And that's not even all. Soul singers like Joann Garrett. Doowop groups like the Esquires. Other groups like the El Dorados and the Danderliers played talent shows there.

Let's give a tribute to the men and women who taught at Dusable, and contributed so much to our culture.

This session was released on LP as Bennie Green with Art Farmer.

I talked about sentimentality in my last post, and defended its place in art, but you can also ignore it altogether. Green and Farmer take "My Blue Heaven" at a bebopper's pace, using the melody as a springboard for great improvisation, pretty much forgetting about Molly and me and the baby, although there's a real sweetness to Farmer's restatement of the melody at the end. And although there aren't any blues in that cozy place with the fireplace, these guys find room for them in their improv.

"Cliff Dweller " is a composition by piano player Cliff Smalls, and it kicks off with some very

complex but driving interplay between Smalls, Addison Farmer and Philly Joe Jones. Smalls worked often with Bennie Green, and there may have been an extra affinity there because Smalls was also a trombonist. Further, they shared a taste for the accessibility of rhythm and blues -- Smalls would go on to be the bandleader for Clyde McPhatter, Smokey Robinson, and Brook Benton.

"Let's Stretch" seems to come with no composer credit, so we'll take it as a collectively improvised Five O'clock Blues, and stretch they do, for a well-spent ten-plus minutes.

They finish the set with a nice moody version of "Gone With the Wind."

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(96)/discogs-images/R-4324011-1361742350-2365.jpeg.jpg) Now, moving on to the digression. Jazz.com's online encyclopedia gives this biographical note:

Now, moving on to the digression. Jazz.com's online encyclopedia gives this biographical note:Bernard Green was born on April 16, 1923 in Chicago, to a family of musicians. His older brother Elbert had played with trumpeter Roy Eldridge in the local Chicago scene, and both attended DuSable High School, a hotspot for music education at the time. It was under the direction of his music teacher at DuSable where Bennie began to study trombone.

At a time when music education is disappearing from our test-obsessed schools, it's good to stop and remember how important it was to the American Century in music, our great contribution to world culture. People talk about musicians, particularly soul musicians, and how they learned their music in church, but there were far more who learned in school.

And what about DuSable High? Who started their music careers there?

Holy smoke.

Here's a list from Wikipedia:

- Gene Ammons — pioneering jazz tenor saxophone player.

- Ronnie Boykins — jazz bassist, most noted for his work with Sun Ra.

- Sonny Cohn — jazz trumpet player, perhaps best known for his 24 years playing with Count Basie.

- Nat King Cole — pianist and crooner, predominantly of pop and jazz works (Unforgettable).

- Jerome Cooper — jazz musician who specialized in percussion.

- Don Cornelius — television show host and producer, best known as the creator and host of Soul Train.

- Richard Davis — bassist and professor of music at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- Dorothy Donegan — jazz pianist.

- Von Freeman — jazz tenor saxophonist.

- John Gilmore — clarinet and saxophone player, best known for his time with the Sun Ra Arkestra, a group he briefly led after Sun Ra's death.

- Johnny Griffin — bebop and hard bop tenor saxophone player.

- Eddie Harris — jazz musician best known for playing tenor saxophone and for introducing the electrically amplified saxophone.

- Johnny Hartman — jazz singer (Lush Life), best known for his work with John Coltrane.

- Fred Hopkins — jazz bassist.

- Joseph Jarman — jazz composer, percussionist, clarinetist, and saxophonist.

- Ella Jenkins — Grammy Award–winning musician and singer educations best known for her work in folk music and children's music.

- LeRoy Jenkins — violinist who worked mostly in free jazz.

- Clifford Jordan — jazz saxophonist.

- Walter Perkins — jazz percussionist.

- Julian Priester — jazz trombone player.

- Wilbur Ware — hard bebop bassist.

- Dinah Washington — Grammy award–winning jazz singer.

And that's not even all. Soul singers like Joann Garrett. Doowop groups like the Esquires. Other groups like the El Dorados and the Danderliers played talent shows there.

Let's give a tribute to the men and women who taught at Dusable, and contributed so much to our culture.

This session was released on LP as Bennie Green with Art Farmer.

Tuesday, February 02, 2016

Listening to Prestige Part 167: Sonny Rollins/Clifford Brown

It's impossible to listen to this session without looking at the date. Three months later, Clifford Brown and Richie Powell would be killed in an automobile accident.

Clifford Brown's contribution to jazz cannot be overstated. As a trumpeter, he ranks among the very best to ever play the instrument.

As a role model, he may have been just as important. At a time when creativity and drug use were all too often linked in the minds of young jazz musicians. Brownie stood out as an example of the creative and innovative heights that a clean-living artist could attain.

Sonny Rollins is a living testament to that. Rollins stands today, by virtue of artistry and longevity, as one the greatest of all jazz musicians, but in 1955, he was putting the pieces of his life back together, and beset by self-doubt. He had kicked his heroin habit, but he had bought too deeply into the myth that heroin and creativity went together, and he had terrifying doubt about his ability to play and grow as a jazz musician, and because of that, he stayed away from New York for a while. He returned to play with Miles Davis, who had followed a similar pattern--addiction, withdrawal, self-imposed exile. But then later on that year, he became a member of the Brown/Roach group, and experienced his true epiphany: the example of a jazz musician who had always led a clean, drug-free life, and whose creativity was unbounded. Rollins later described Brown's effect on him as "profound."

Brown hit New York in 1953 and appeared on several Blue Note albums, then signed on for the Lionel Hampton European tour, where he recorded extensively with Art Farmer, Gigi Gryce and others of that contingent.

Returning stateside, he joined Art Blakey's quintet (they weren't the Jazz Messengers yet), and an engagement at Birdland yielded enough material on one night of live recording to make several albums for Blue Note (the recording notes list some tunes as being from the fifth set). Then he joined forces with Max Roach, to create one of jazz's most legendary quintets, and they made a series of classic albums for EmArcy. EmArcy also had some of the finest jazz singers around, and they had the good taste to back them with jazz greats instead of syrupy pop arrangements, so we have Brown with Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughan and Helen Merrill. And -- not at all syrupy -- they made an album of standards with the Neal Hefti orchestra.

Brown did some work on the West Coast with different configurations, and in 1955...well, if you

could go back in time to the 1955 Newport Jazz Festival, just so you could catch the now-legendary Miles jam session / audition for George Avakian, you might have missed another remarkable jam session -- Brubeck and Desmond with Clifford Brown, Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan. "Tea for Two" was captured from that session, and it's not the greatest recording quality, but still....

Rollins joined the quintet in 1955, replacing Harold Land, and they were able to record, in February and March, for both EmArcy and Prestige. The EmArcy recordings mixed standards and originals by Brown; this one has three standards and two Rollins originals.

Both of the two originals have become jazz standards, with "Valse Hot," in particular, now a favorite of a newer, 21st century generation of jazz musicians. There aren't all that many jazz waltzes--Bill Evans's "Waltz for Debbie" is one that springs to mind, and of course John Coltrane's reworking of "My Favorite Things."

"Pent-Up House" seems to have become a favorite of gypsies, with Stephane Grappelli and the gypsy jazz contemporaries, The Rosenberg Trio. Tito Puente has also recorded a version that burns down the house. But this pent-up house was certainly made for burning, as is made abundantly clear in this original version. Rollins and Brown trade blistering solos, and there's plenty of room for Richie Powell to stretch out as well -- and Max Roach, whose solos throughout the session are a reminder of how great jazz drumming can be, and also how far recording engineering has come.