Kenny Clarke was beginning to feel a little claustrophobic within the strict confines of the MJQ. One of the pioneers, and one of the most prolific drummers of the bebop era, He was the original house drummer at Minton's, which means he played with everyone -- and as the modern jazz decade progressed, everyone wanted him, or Max Roach or Art Blakey, to play with them.

In 1955, after severing his ties with the MJQ, Clarke made fouralbums for Savoy as leader of co-leader:a septet session with Ernie Wilkins; The Trio, in which all three players--Clarke, Wendell Marshall and Hank Jones--go co-credit; Telefunken Blues, for which he enlisted MJQ-mates Jackson and Heath, along with a front line of Henry Coker, Frank Morgan and Frank Wess; and a third album featuring a rhythm section of Horace Silver (Hank Jones on one track) and Paul Chambers, and a front line of Donald Byrd on trumpet and Jerome Richardson on tenor sax and flute. He also gave two young brothers their first exposure on record: a trumpeter and alto sax player named Nat and Julian Adderley. It's safe to say that Cannonball made an impressive debut--impressive enough that Bohemia After Dark has often been re-released under his name.The session was successful enough that two weeks later the same two brothers and the same rhythm section recorded under Cannonball's name, and two weeks after that under Nat's name, with Jerome Richardson replacing Nat's brother.

He also recorded with Gene Ammons (Prestige), Eddie Bert (Savoy), Donald Byrd (Savoy),Milt Jackson (three albums on Savoy), Hank Jones (two more on Savoy in addition to The Trio), Duke Jordan and Gigi Gryce (Savoy), Lee Konitz and Warne Marsh (Atlantic), Charles Mingus (Savoy), Thelonious Monk (Riverside), and Little Jimmy Scott (Savoy).

And that's just the tip of the iceberg. He also recorded with:

- Johnny Mehegan, best remembered for his seminal books on jazz improvisation.

- Wally Cirillo (Cirillo's album, also featuring Mingus and Teo Macero, included what is probably the first recorded jazz composition written in a 12-tone scale).

- Johnny Costa, whom Art Tatum dubbed "the white Art Tatum" and who later became musical director of Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood. It's nice to remember, in this day of disappearing live music, that Fred Rogers employed a live jazz trio, which played (per Wikipedia), "the show's main theme, the trolley whistle, Mr. McFeely's frenetic Speedy Delivery piano plonks, the vibraphone flute-toots as Fred fed his fish, dreamy celesta lines, and Rogers' entrance and exit tunes."

- Chuz Alfred, who made two albums as leader in 1955, then gave up jazz to play with Ralph Marterie's dance orchestra, then returned to Columbus, Ohio, where he became a charter member of the Columbus Musicians' Hall of Fame. And you thought the only musicians' hall of fame in Ohio was the one in Cleveland.

- Johnny Coates, who as Jazz King of the Poconos, employed the young Keith Jarrett as a drummer.

- Mike Cuozzo, described by Marc Myers of Jazzwax as "a gifted player... a Lester Young sound with a Lennie Tristano vibe." He gave up music to become a building contractor in New Jersey, but not before making an album with Mort Herbert, who would become deputy district attorney of Los Angeles,

- Al Caiola, who branched out from jazz to record hit versions of the themes from The Magnificent Seven and Bonanza, and who recorded with Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Percy Faith, Buddy Holly, Mitch Miller, and Tony Bennett, among others.

Not only is that just 1955, that's just Savoy.

Clarke might have been able to keep up this prodigious schedule and still make dates with the MJQ, but he was also feeling claustrophobic about America, By 1956, he was a full-time resident of France, where he could make more money and deal with less racism. He played many sessions with visiting American musicians, and led the Clarke-Boland Big Band with Belgian pianist Francy Boland.

Connie Kay had followed Kenny Clarke before he followed him into the Modern Jazz Quartet. He became the house drummer at Minton's.

Before that, as a teenager, he had worked at a club called Ann's Red Rose in his Bronx neighborhood, getting the gig a week after he had bought his first drum kit. The house drummer for the Red Rose had quit suddenly, and someone at the bar said "Well, there's a drummer around the corner because I hear him practicing every night as I come home from work." So he played for comedians, singers, tap-dancers and chorus girls (from the NY Times obituary and a NY Times profile).

He moved from there into the jazz world, playing behind every major figure at Minton's, and also in Lester Young's band for several years. He was also putting his Ann's Red Rose experience to good use as the drummer for various rhythm and blues ensembles, including that of Frank (Floorshow) Culley, who had had a hit for Atlantic Records with "Cole Slaw." Culley brought him in to Atlantic in early 1951 to record a demo for The Clovers, who had just signed with the label. The song was "Don't You Know I Love You," and the bass player didn't show up for the session, so Kay had to double his part on the bass drum. He got paid for the gig, and thought no more about until a couple of weeks later, when "I'm driving my car and hear the tune and I say, 'Wait a minute, that sounds like the tune we made a demo of.' A week later I went to Atlantic and I went into Ahmet Ertegun's office and he said: 'Man, I'm glad to see you. We've been trying to find you. I like the beat you used on that record.' From that time on they kept calling me for record dates. When I couldn't make record dates, they'd postpone them.''

Supposedly, the "concept album" began with Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which began with a vague idea by the Beatles to make an album that would represent a collection of songs by a fictitious village band, an idea which got discarded pretty quickly, but floated around the album sufficiently that "concept album" became the goal of mostly some pretty pretentious rock groups. If you wanted a real concept album, what about My Fair Lady Loves Jazz or Dave Digs Disney, or for that matter any Broadway show original cast album? Or Louis and the Angels? Or Birth of the Cool, which wasn't even made as an album but is still one of the greatest concept albums of all time?

Anyway, Concord is a concept album in that the concept was that it would be an album. It was the third recording session scheduled by Prestige to produce a full 12-inch LP's worth of music: in this case, six selections, and over 36 minutes worth of music.

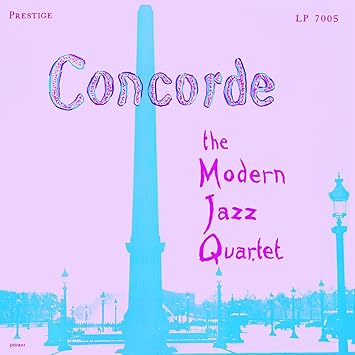

It's an album that's mostly standards. Perhaps in Lewis's mind, the group already had one foot out the door, so they were saving original material for Atlantic--although in fairness, the MJQ tended to be standard-friendly until later in its career, and the first Atlantic album only had three originals. The originals are Jackson's "Ralph's New Blues" and Lewis's title track. I'd wondered if "Ralph's New Blues" was a tribute to Ralph Ellison -- I'd sort of hoped it was -- but appears to be for jazz critic Ralph J. Gleason, which is pretty good too. It's built on an irresistibly bluesy riff, and is the catchiest number on the record. "Concorde" is another Francophile nod from Lewis, and inspired the Eiffel Tower cover of the album. It has a richness of tone, a catchy melody, and an uptempo swing.

Lewis and Jackson know how to sustain a note for dramatic effect, and they know how to let loose a torrent of notes. But as always, the the MJQ is a quartet, not a leader and sidemen, and you're always aware of the contribution each member is making to the sound.

"Softly as a Morning Sunrise" was released as a two-sided 45. The album's initial release, as noted, was the 12-inch LP.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb()/discogs-images/R-2615020-1293370836.jpeg.jpg)

2 comments:

Tad--The monument on the cover of the "Concorde" album is not the Eiffel Tower. It's the Place De La Concorde, hence the album title.

And Johnny Mehegan is the John Mehegan we used to listen to at Dameon's Cafe in Westport on mamy a Saturday night.

Pax et Musica,

Bob B.

Careless on my part.

Post a Comment