Avakian wanted Miles to put together a group that he'd work with consistently. Today, using one of the words I've grown to loathe, this would be called a brand. It was opposite from the approach Bob Weinstock had taken, having Miles record with different musicians in different combinations.

So if Miles had those couple of toes out the door, he had to have been at least to some degree auditioning young musicians. He obviously wasn't going to recruit Milt Jackson or Percy Heath, but the others were all possibilities.

Miles had kicked his heroin habit by this time, and he was understandably impatient with young musicians who had not. That meant young Jackie McLean, then 24, would not make the cut. Miles said of him later,

Jackie was so high at this session that he was always scared he could not play anymore. I don't know what's the shit was all about, but I have never hired Jackie after this session.McLean only appears on two cuts "Dr. Jackle" and "Minor March." Miles would have the same problem with the saxophonist he did choose, John Coltrane, and they went through some rough patches, with Miles at one point firing Trane and disbanding the quintet, then putting it back together.

Art Taylor, at 26, was beginning a long association, not with Miles, but with Prestige. He may have been the drummer on a 1954 session with Art Farmer (this is up in the air), but he was definitely on this session. He would work off and on again with Miles over the years. but we would become known as the "house drummer" for Prestige, working on many sessions. Unlike Miles, he would also record again with Jackie McLean--and he had worked with him before. The two of them, and Sonny Rollins, had grown up in the same Harlem neighborhood, and had played music together as teenagers.

For 24-year-old Ray Bryant, 1955 was his breakout year, but he had actually first recorded at age 14.

This was in his native Philadelphia, in a band that included John Coltrane (on alto) and Benny Golson. And continuing my policy of never meeting a digression I didn't like, especially when it involves the twisting careers of working jazz musicians. the band was led by drummer Jimmy Johnson, who must have kept working and getting his name known in jazz circles, because 15 years later he was hired by Duke Ellington.

Trombonist Gino Murray later worked with Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt, but doesn't seem to have recorded with them,

Bassist Tommy Bryant didn't quite achieve the renown of his younger (by one year) brother, but he had a solid career, playing and recording with both his brother and Benny Golson from the 1944 session, and also with Dizzy Gillespie, Jo Jones, Roy Eldridge, and may others.

But the really interesting career out of this aggregation belongs to trumpeter Henry Glover. In the mid-1940s, that burgeoning time for independent jazz and rhythm and blues labels, he was touring with Lucky Millinder, and met Syd Nathan, who had recently started King Records as a country label, but was discovering that there was a market for the sort of jazz that bands like Millinder's played, which was soon to be called rhythm and blues.

Nathan hired Glover to build a rhythm and blues presence on his label, and, incidentally, to build him a studio. But Glover ended up doing more than that. Originally from Arkansas, Glover had grown up listening to country music on the radio, and -- like his contemporaries Ray Charles, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino-- loving it. So Glover found himself producing country artists like Cowboy Copas, Hawkshaw Hawkins (those two would die int he plane crash that killed country legend Patsy Cline), Grandpa Jones, and the Delmore Brothers, with whom he co-wrote "Blues, Stay Away From Me," which became their signature song and a country music standard. Glover was almost certainly the first successful African American producer in the country field.

He had his first rhythm and blues hit with Bull Moose Jackson, and went on to record Lucky Millinder, Tiny Bradshaw, Wynonie Harris, Bill Doggett, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, Little Willie John, and Jame Brown. Later moving to Roulette, he came back into the jazz fold, producing records for Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington and Sonny Stitt, as well as creating a rock 'n roll presence on Roulette with the k\likes of Ronnie Hawkins. He became close to Ronnie Hawkins' backup band, later to become The Band, and in the 1970s moved to Woodstock where he helped Levon Helm found his own independent label. As a songwriter, he wrote "Drown in My Own Tears," a hit for Ray Charles, and one of the biggest hits of the 60s, "Peppermint Twist."

The record that Glover, Bryant and the gang made was never released, and the personnel list for the session comes from the memory of Benny Golson.

Bryant would go another four years before getting a record date, this time with Tiny Grimes' Rockin' Highlanders. Grimes was another one of those cats who made music at the intersection of jazz and R&B. I know that tenor sax great Red Prysock, who was on this session, quit Grimes shortly thereafter because of the bandleader's insistence that his band members all wear kilts. So...Ray Bryant in a kilt? Or Philly Joe Jones?

Then nothing till 1955, Bryant's breakout year. Before the Davis session, he had recorded with Toots Theilemans on Columbia, with Betty Carter on Columbia subsidiary Epic (the label for which he would record most often, and then with the same trio (Wendell Marshall, Jo Jones) under his own name. He would record again for Prestige in December, with Sonny Rollins.

Miles and Milt Jackson had played together before, on the notorious Miles/Monk session, They play off each other beautifully here, and so does Jackie McLean. Although he's only on two tracks. "Dr. Jackle" and "Minor March." He gets composer credit on both, and fairly extensive solo space. "Bitty Ditty" is a Thad Jones composition that's been widely recorded; "Blues Changes," also known simply as "Changes," is Ray Bryant's. All the cuts are extended--from 6 1/2 to 9 minutes long -- giving plenty of room for improvisational experimentation.

Again, we have to grateful to Weinstock and Prestige for giving Miles this kind of exposure, in different settings and with different musicians. And, as in the case of this session, with different musicians bringing different material.

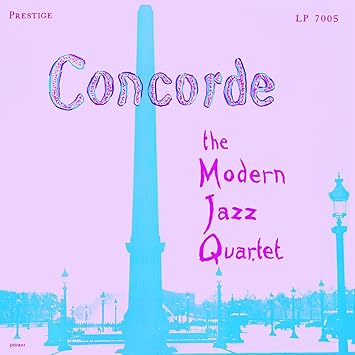

The session was planned for a 12-inch LP, with just over 15 minutes on each side, but the album wasn't released right away, for whatever reason. It came out as Prestige PRLP 7034, and is variously known as a Miles Davis or Miles Davis/Milt Jackson album (see the typefaces on the album cover.

The cover art is that muted color photo reproduction which would appear on a lot of Prestige covers; the photo is by Bob Weinstock.

.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb()/discogs-images/R-2615020-1293370836.jpeg.jpg)