Jimmy Raney was back in the studio twice in the winter of 1955, February 18 and March 8, with the same lineup. It included his mentor Hall Overton, who had not been part of his session from the previous August, which had featured two horns but no piano. One of the two had been Phil Woods, who went on, as we know, to have one of the most distinguished careers in jazz history, although he and Raney were not to record together again. The trumpet player for that earlier gig, John "Doc" Wilson, who is back for these next two, also went on to have a career no less admirable, if less acclaimed, as an arranger and educator.

Jimmy Raney was back in the studio twice in the winter of 1955, February 18 and March 8, with the same lineup. It included his mentor Hall Overton, who had not been part of his session from the previous August, which had featured two horns but no piano. One of the two had been Phil Woods, who went on, as we know, to have one of the most distinguished careers in jazz history, although he and Raney were not to record together again. The trumpet player for that earlier gig, John "Doc" Wilson, who is back for these next two, also went on to have a career no less admirable, if less acclaimed, as an arranger and educator.Wilson's first recordings were on these Jimmy Raney sessions. He went on to record with Bob Brookmeyer and Gerry Mulligan, but recording with famous names was not to be his major contribution to the jazz world. And interestingly, though he played with one of jazz's great arrangers, he does not list Mulligan as one of his most important influences.

Wilson's first big time gig was with the interesting but short-lived bebop aggregation that Benny Goodman put together with Zoot Sims and Wardell Gray. He would learn a lot from Goodman, including, as he told Nate Guidry in a profile in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the way that

After Goodman, he played in bands led by Pete Rugolo, Neal Hefti and Claude Thornhill, all top arrangers. But he says his most rewarding experience was playing in the band led by Eddie Sauter and Bill Finegan, who first made their reputation arranging in the golden years of swing, Sauter for Red Norvo, Benny Goodman and others, Finegan for Glenn Miller:

...when the band wasn't swinging the way he wanted, Benny would have a rehearsal early in the morning without the rhythm section so we could get our own swing thing going...I found later in my career that that's a great technique. If you've got a great rhythm section and the music isn't swinging, it's not the rhythm section's fault.

Those guys had some really novel ideas when it came to arranging. The effects of that band are still felt today. They used woodwind doubles, extra percussions that are now commonplace. But when they started doing it, it was new.The Sauter-Finegan orchestra was swimming upstream against the rock and roll tide of the 1950s, and Wilson found himself swimming against the same tide in the 1960s, as the Beatles swept away everything in their path, including jazz. Wilson recalls

...things in New York were getting bad. Musicians were going from working six days a week to one or two days. I ran into Kenny Dorham working in a music store on 48thWilson went back to school, got a doctorate in music from NYU, and landed a teaching job at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh in 1972. There wasn't much call for jazz in higher education then -- in 1972, only 15 colleges in the US offered degrees in jazz studies. But Wilson had his Ph.D., so he was able to get hired as Duquesne's band director, conducting classical music and wind ensembles, and eventually to set up a jazz program.

Street. The great Kenny Dorham couldn't find work. I had my trumpet stolen, so I go into this store, and I'm in the basement trying these different horns, and here comes Kenny and he said, 'I heard some of those licks you were playing, and I had to come down and see who was playing that.'

Wilson and Raney mesh beautifully here. Raney had a wonderful sense of how to coordinate a guitar and horn, and it didn't hurt to have Rudy Van Gelder engineering the sessions. Replacing Bill Crow and Joe Morello are Teddy Kotick and Nick Stabulas.

The tunes are originals and standards on the first session, all standards on the second. Mostly Raney takes a fairly loose approach to the melodies, even on the head, and he makes it work. With the exception of "Someone to Watch Over Me," where the pure beauty of the melody engages him briefly.

I wanted to do a portrait of John "Doc" Wilson, but I can find no pictures of him anywhere on the Internet.

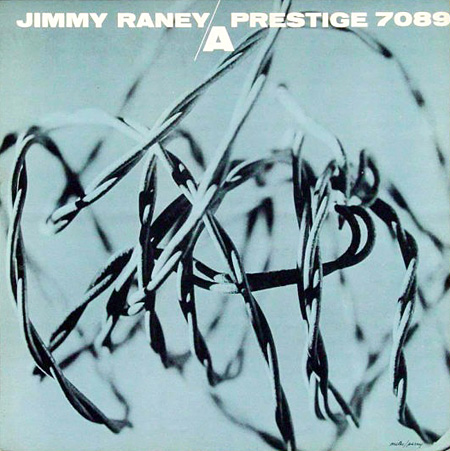

These sessions were combined on a 10-inch LP, and later included on the 12-inch Jimmy Raney - A.

No comments:

Post a Comment