And wondering leads to Google, and Google led me to this interview with Charles, which I had not seen before, where he talks about his West Coast sojourn:

One day in late 1952 or early 1953, after I had recorded those New Directions dates, he asked if I wanted to move to the West Coast to be the A&R director out there. The West Coast was a completely new scene for East Coast labels. They didn't quite get what was happening there, but they knew they had to be in on it.

"The first thing Bob wanted me to do was record Wardell Gray, which I did. Wardell was the hot guy out there. He and I had played together in Benny Goodman's group in the late 19940s. Bob had wanted me to put together a couple of sessions and record standards. But I had other things in mind. I wanted to put different musicians in challenging musical situations to see what came of it.

You don't have to have read too many of my blog entries to know that in my opinion, bringing Wardell Gray into any project is bound to be a good idea. I've written about that session. Listening to it, and especially listening to this session, I also couldn't help wondering whether Charles completely bought into Weinstock's "get together and jam" philosophy. Well, no. There was only one Bob Weinstock, and he made it work. He had a fan's enthusiasm, and it carried over into the making of some of the greatest jazz records ever made, so you'll never hear me knocking his philosophy. But it was a fan's philosophy; a musician's is bound to be different. So from the same interview, here's Teddy Charles talking about rehearsal, and also about tapping into the emerging West Coast sound:

In most cases, I’d get guys together and we’d run through the material I wrote. If it worked, we’d go into the studio. Or we’d have a date set, and we’d be in my apartment rehearsing. I also played quite a bit at the Lighthouse down at Hermosa Beach.This interview was conducted by Marc Myers for his JazzWax blog. He's one of the great interviewers, so I strongly recommend reading the whole thing...and his blog is a treasure. Charles told Myers about one session he tried to put together with Stan Getz, Chet Baker and Al Haig, which ultimately had to be abandoned, as he discovered that not all great musicians had a feel for what he wanted to do -- "Stan could play anything, of course, [but] the music wasn't happening and felt forced."

When I got out on the West Coast, I didn’t want to do the West Coast cool jazz thing that was so popular then. Frankly I didn’t care for the West Coast style of playing. The music was too laid back and didn’t have the sound. Not enough urgency. Instead, I brought an East Coast sound I was experimenting with out there, and I used West Coast guys to play it.

I would have thought Shorty Rogers an odd choice for a Teddy Charles session. I wasn't that familiar with his work, and thought of him as a typical West Coaster, with an ear toward the pop market. I'd heard his album of jazz takes on contemporary pop songs, Chances Are It Swings, and I knew he'd done some Hollywood stuff, like The Man With the Golden Arm. I hadn't realized he had such an interest in experimental music. When you look at some of his credits, you can see why Charles gravitated toward him. From Wikipedia:

I would have thought Shorty Rogers an odd choice for a Teddy Charles session. I wasn't that familiar with his work, and thought of him as a typical West Coaster, with an ear toward the pop market. I'd heard his album of jazz takes on contemporary pop songs, Chances Are It Swings, and I knew he'd done some Hollywood stuff, like The Man With the Golden Arm. I hadn't realized he had such an interest in experimental music. When you look at some of his credits, you can see why Charles gravitated toward him. From Wikipedia:In the 1950s, when Igor Stravinsky began experimenting with dodecaphony, one of the twelve-tone techniques originally devised by Arnold Schoenberg, Stravinsky was very impressed with Rogers's playing, which, as Robert Craft reports in his book Conversations with Stravinsky, influenced the composer's 1958 choral work Threni.Rogers is the sole horn on the first four tracks, from the August 21 session, and he works well with Charles, understanding and developing his ideas. I think the group is even better when Jimmy Giuffre joins them on August 31 -- of course, this is also ten more days of rehearsal.

Shelley Manne was one of the most ubiquitous, and one of the most commercially successful musicians on the West Coast. His albums like My Fair Lady Loves Jazz, with Andre Previn, showed that you could satisfy the demands of art and the market at the same time. But did his comfort level stretch far enough to accomodate the seriously experimental sounds of Teddy Charles?

Shelley Manne was one of the most ubiquitous, and one of the most commercially successful musicians on the West Coast. His albums like My Fair Lady Loves Jazz, with Andre Previn, showed that you could satisfy the demands of art and the market at the same time. But did his comfort level stretch far enough to accomodate the seriously experimental sounds of Teddy Charles?

Oh, god, yes. Rogers and Giuffre work beautifully with Charles, but Manne does more. He brings ideas that take Charles to a new level. As I listened to these sides over a number of times, which is what I do in writing one of these entries, I found myself more and more looking forward to "what's Shelly going to do next?" Give a listen and see what I mean.

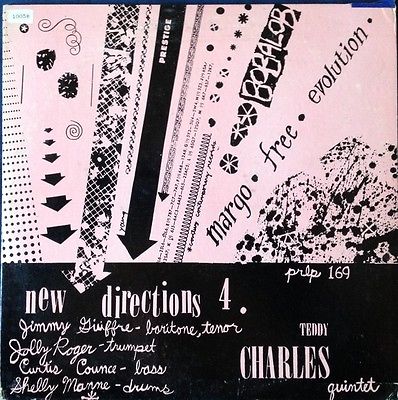

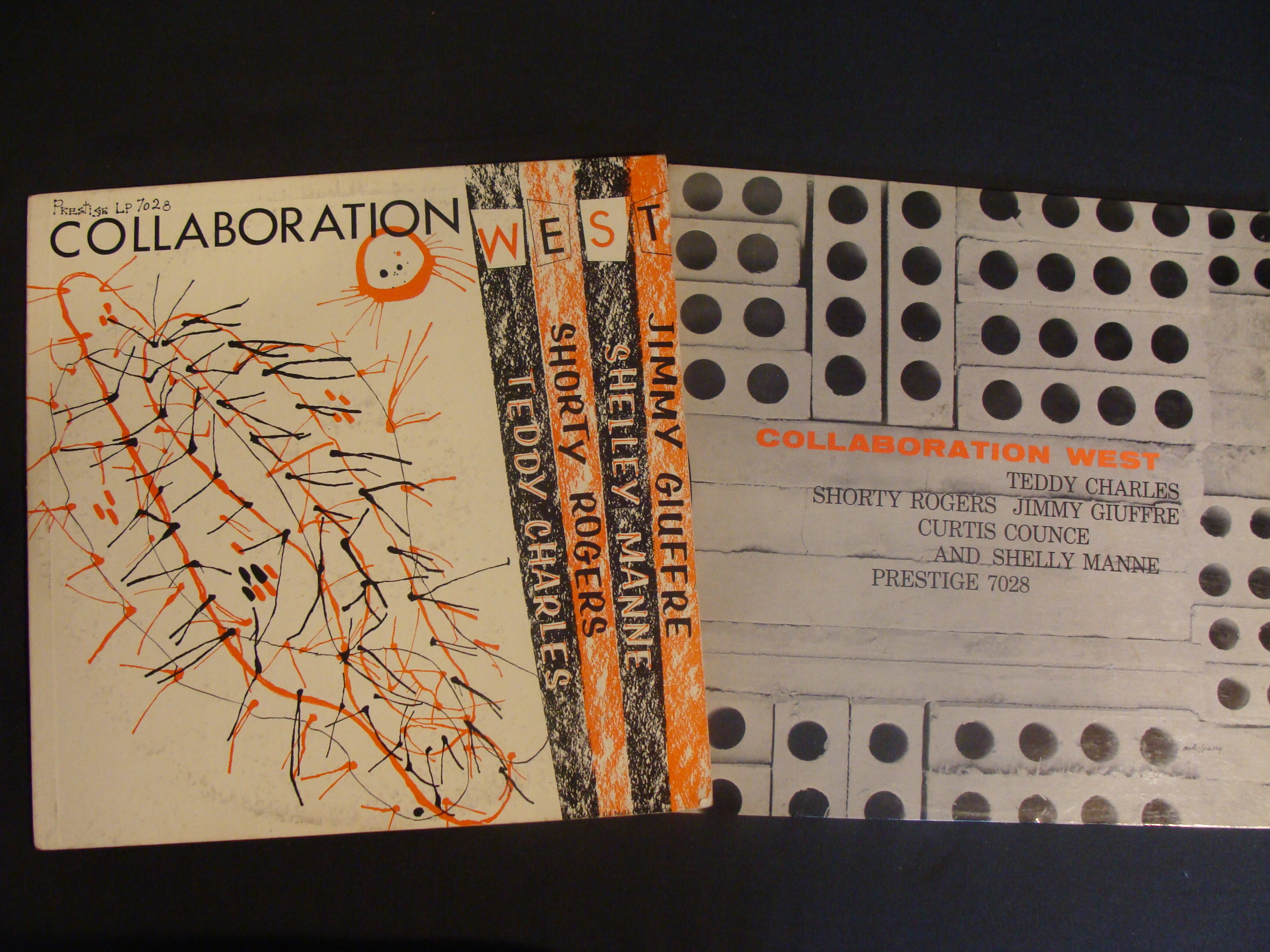

These came out on two 10-inchers, New Directions 3 and 4, and again in 1956, when Prestige had moved to the 12-inch LP standard, as Collaboration West - Teddy Charles/Shorty Rogers.

No comments:

Post a Comment