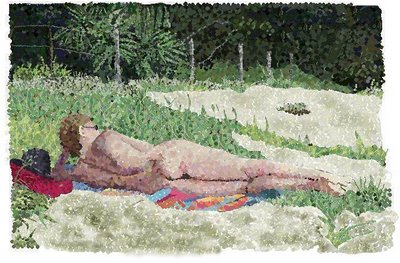

An article by Kandy Harris in the

Saugerties Times quotes me -- correctly -- as using Microsoft Paint 'to create something he calls - with tongue firmly planted in cheek - '21st century pointillism.'" (She also slightly misreprents me in saying "Richards claims he is the only artist working in the genre," a claim I would never make. I think I said I was the only artist that I knew of working with Microsoft Paint in just this way. There are many artists doing interesting work "painting" with graphics programs, and you can see some of them at

Don Archer's

Museum of Computer Art. But this is a quibble with a very good article.)

Anyway, I digress. My point was the firmly-in-cheek tongue placing for "21st century pointillism," a term offered to me by James Cox of the

James Cox Gallery -- thanks, Jim. I present the label with tongue firmly planted in cheek, but not the art. I take what I do seriously, even though I'm a little shy about labeling it seriously.

My stepfather, Harvey Fite, had the same problem, of course. His line in the sand came even earlier -- he didn't just resist categorizing his great masterwork, even resisted naming it. For years he called it "High Woods," after his beloved community where he had chosen to settle and create. As it started growing in reputation, people started looking for a name. The brilliant photographer

Maria Layacona

Maria Layacona, did an article on Harvey in the early Fifties, and called it "Fite's Acropolis in the Catskills" (photos by Maria included here).

Harvey was honored, but a little embarrassed, and eventually he realized he was going to have to give his work a name.

"Composers have it easy," he would joke. "They don't have to name things, they just number them -- Opus 1, Opus 2, and so forth." From the joking came a name -- Opus 40. Not Harvey's fortieth work, but forty years of work.

As for "environmental sculpture," "earthwork," or similar genre-defining names, Harvey never considered them. In subsequent years, it's occurred to me that Harvey was working within two artistic concepts that didn't have names while he was doing the work, but have acquired names since. One, of course, is "environmentalism." Harvey was very much aware of nature as Opus 40 developed under his hands": the lines of the mountain that became its backdrop, natural pools, trees. He was aware that the quarrymen who were his High Woods forefathers had carved a life and a living out of the native bluestone, but they had not left nature the way they found it. And with respect for them, but also respect for nature, he set out to make amends to nature for what human beings had inflicted on her.

The second name that Harvey never heard or used was "multiculturalism." But Opus 40, the first glimmerings of which stirred in Harvey during his residency in Copan, contains within it Harvey's sweeping love for, and awareness of, so many sculptural traditions.

How much are we limited by naming what we do? In many ways not much, and all too often artists who say "my work resists category" mean, whether they know it or not, "my work is too formless and uninteresting to have a category." Certainly "landscape," or "sonnet," or "concerto" don't limit an artist in any important way, and they do give him or the boundary and structure that art needs. Even Opus 40, which really is sui generis, can be categorized as "dry key stone masonry" or probably even "environmental sculpture," though it wasn't a current phrase during Harvey's lifetime.

Other labels are more problematic. The Beats mostly chafed against being called Beats. Pound founded Imagism and then disavowed it. The Impressionists exhibited together because no one else would have them, but I don't think they thought of themselves as having a clubhouse and a secret handshake.

So what's wrong with "21st Century Pointillism"? Maybe the same thing that's wrong with "claims he is the only artist working in the genre." Too self-aggrandizing? A lot of poets, myself included, are nervous about calling themselves "poets." "Poet" is something we aspire to be, something that Keats and Dante were.