LISTEN TO ONE: A Little Barefoot Soul

In my mind, Bobby Timmons was Blue Note. But the mind can play tricks. Timmons did record extensively on Blue Note, as a member of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, and before that, with Kenny Dorham's Jazz Prophets, and with Lee Morgan. But to my surprise, He never recorded as a leader with Blue Note. His first record as a co-leader (with Clifford Jordan and John Jenkins) was on New Jazz. Then, starting in 1960, he recorded a series of albums for Riverside, while continuing to play and record with Blakey through 1961. This session marked his return to Prestige, the first of seven albums he would make for the label over the next two years.

Timmons has been something of a controversial figure in jazz criticism, with "underrated" being a term applied to him with surprising regularity, while other critics have suggested there wasn't much to him below the surface--that he was basically just a guy who wrote simple tunes, a few of which have clicked to become hits and jazz standards.

His recording career is curious also. Between 1958 and 1961, from his first emergence on the New York Scene through his associations with Art Blakey and Cannonball Adderley, he was much in demand, playing on sessions with Pepper Adams, Chet Baker, Kenny Burrell, Arnett Cobb, Kenny Dorham, Art Farmer, Benny Golson, Dexter Gordon, Lee Morgan and others. Then nothing. He continued to tour with a trio and to make records under his own name through the 1960s. Perhaps it was his heroin addiction that made him too unreliable as a sideman. His substance abuse problem was a serious one, and it led him to an early grave.

But soul jazz was marketable, and Timmons was a marketable name. "Moanin'" and "Dat Dere" had become hugely popular jazz tunes, the more so because they had had lyrics attached to them by two masters, Jon Hendricks and Oscar Brown Jr., respectively.

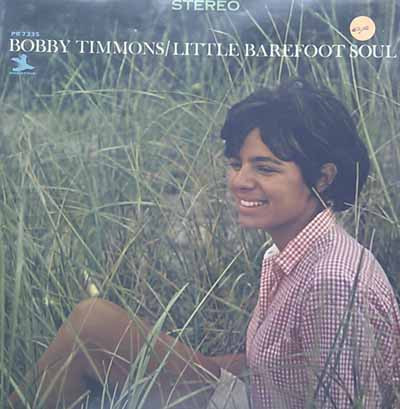

Certainly his labels weren't shy about pushing the soul connection. Riverside, for whom he recorded from 1960-64, gave his albums titles like This Here is Bobby Timmons (included "Moanin'," "Dis Here" and "Dat Dere"), Soul Time, Sweet and Soulful Sounds. His debut album for Prestige was, if anything, even less subtle...Little Barefoot Soul,

There is nothing on the album anywhere near as catchy as Timmons's big three, for all the catchy titles. So this may not be the place to look for Timmons, the simple soul tunesmith.

But it might be a good place to start considering Timmons, the underrated jazz pianist. Rather than depend on the restatement of catchy riffs, he engages here in thoughtful and often daring improvisation. He's accompanied on drums by King Curtis sideman Ray Lucas, who keeps him honest, and Sam Jones, who spurs his creativity. He would work with a variety of sidemen in his two years with Prestige, probably a result of his drug-fueled unreliability, but this is an excellent pair.

The producer credit for the session is a little ambiguous: longtime Prestige producer Ozzie Cadena is credited with "supervision," producer is listed as Joel Dorn, who also wrote the liner notes.

Dorn was an interesting guy. He knew from age 14 that he had one ambition in life--to produce records for Atlantic, and at that young age he started writing to Nesuhi Ertegun, making his case. Ertegun finally relented, telling him he could produce one album by an artist of his choice. He chose Hubert Laws, and it was the beginning of a fabulously successful career, which included discovering the Allman Brothers and the Neville Brothers, and winning a Grammy for his production of Roberta Flack's "Killing Me Softly with His Song."

He recorded Laws for Atlantic in April of 1964, the fulfillment of his lifetime ambition at age 22, so one has to wonder what he was doing in Englewood Cliffs in June of that year, working with a new Prestige artist. Perhaps Ertegun was waiting to see how The Laws of Jazz did before making a commitment. And maybe the problems Dorn enumerates in his somewhat defensive liner notes for the album might not have arisen had his head not been too swiveled toward the orange, black and green of Atlantic. The album, Dorn reports,

was supposed to have been a quintet date. But when Bobby arrived at the studio only one musician, Sam Jones, was on hand. Then came the inevitable phone calls with excuses from the sidemen for not showing up...So with practically two hours of recording time eaten away...it seemed the session would have to be cancelled. Fortunately, someone remembered that Ray Lucas was in town...and within half an hour had his drums set up and ready to record.

Dorn also refers, while declining to get into specifics, to "an air of antagonism...between the artist, the A&R man, and the engineer." It's not clear whether he's referring to himself or Cadena, but in any event, he was off to the Atlantic recording studios and Tom Dowd after this, while Timmons continued working with Cadena, Van Gelder, and a different crop of musicians. And after two tunes that had to be thrown out because Lucas had trouble finding a groove with two musicians he'd never met before, everything clicked with "A Little Barefoot Soul" (the first word was dropped for the album title), and from there on things went smoothly. Perhaps the unexpected loss of two front men forced Timmons to improvise more than he had intended to, and the results are salutary.

The title track, with "Walkin', Wadin', Sittin', Ridin'" on the flip side, was released as a 45 RPM single.