LISTEN TO ONE: Eerie Dearie

Booker Ervin is still in the middle of his six-year, 13-album sojourn with Prestige. Prestige knew what they had with Ervin, in more ways than one. They recognized his outsized talent--he was one of the most important young saxophone players to come along in the early 1960s. But they also could relate to his music. The label was very much staying abreast of current trends in jazz, recording some of the best of the avant gardists and the back-to-basics soul jazz artists, but its heart was still with the mainstream bebop that excited 19-year-old Bob Weinstock to form a new label in the first place. Indeed, when another decade rolled around and Weinstock sold the label, retiring from the business, he said that it was time--the music he loved wasn't being made any more.

Booker Ervin's sound, as Ira Gitler said in his liner notes to The Blues Book, was "of the '60s. but it has not lost touch with the tap roots of jazz." Gitler, one of the great chroniclers of the golden age of jazz represented by Prestige, went on to describe Ervin's sound as only he could:

Booker's phrasing (the highly-charged flurries and the excruciating, long-toned cries), harmonic conceptions (neither pallid nor beyond the pale) and tone (a vox humana) add up to a style that is avant-garde yet evolutionary, and not one that bows to fashion or gropes unprofessionally under the guise of "freedom."

Probably the gateway album to the new avant garde was John Coltrane's Giant Steps, the first one he made after leaving Prestige for Atlantic, with new harmonic ideas but still accessible to the jazz lover raised on bebop. Ervin's "avant garde yet evolutionary" style can be said to place him in the Giant Steps generation, although Ervin's approach is nothing like Coltrane's. Like Coltrane's album of four years before, it has the thrill of the new, while still being rooted deep in solid earth--in this case, the earthy truth of the blues.

The group recorded five tunes for this session, four of which were included on The Blues Book. The fifth, "Groovin' High," would be the title cut of a later album culled from various Ervin sessions. The Blues Book has two tunes on each side of the vinyl release, one long, one short. The A side is "Eerie Dearie," checking in at 14:30, and "One for Mort," 6:24. '

"Eerie Dearie" is the whole package. It begins with a soulful piano vamp from Gildo Mahones, then a solid blues riff from the horns, opening up the door for an extended solo from Ervin. And yes, it's avant garde but evolutionary. Ervin shows just how free you can get, while still with a solid anchor in the blues. With fourteen and a half minutes to play around in, everyone gets a chance to solo, but it's Ervin you come away with.

Mahones is a solid Prestige veteran. Jones was new to the East Coast when he made this recording, and probably new to Ervin. Gitler, in his liner notes, makes a point of commending Don Schlitten as producer for putting the personnel together.

Jones had been active on the West Coast since 1961, recording with Bud Shank, Gerald Wilson, Red Mitchell, Harold Land and others, including backing Sarah Vaughan in a series of West Coast recording dates in May and June of 1963. He came east to work with Horace Silver, and he had done one live recording with Silver's quintet, but it would not be released until 20 years later, so this was his real East Coast unveiling. He did work with Silver for a while, recording with him in late 1964 and early 1965, and he was to have a couple more Prestige gigs, one with Charles McPherson and one leading his own quintet.

Schlitten also brought in Richard Davis and Alan Dawson, about whom Gitler coments,

Although they had not met until they did The Freedom Book...and play together only in the studio on an Ervin recording, D&D are about as tightly fused a duo as you will encounter anywhere in the annals of jazz. There is no loss of rapport from one date to the next. They arrive, unpack their instruments, and they're off and flying.

They would unpack together again on Ervin's next album. Then Reggie Workman would replace Davis for a couple of sessions, and Davis would return for Ervin's last hurrah on Prestige in 1966.

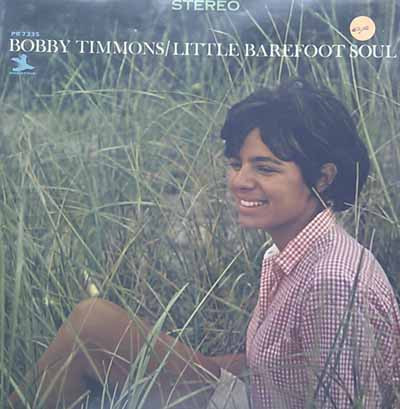

.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3303561-1324846735.jpeg.jpg)

:format(webp):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-13430341-1554052732-7820.jpeg.jpg)