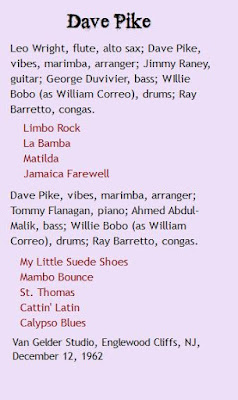

As promised, a new Dave Pike with this, his third and last album for Prestige. Pike would re-invent himself often, like so many jazz musicians in this swiftly moving art form, from Miles Davis on. This, however, is not so much a reinvention as a shift in emphasis, away from the Latin rhythms, on to a more mainstream sound. How much of this was the result of commercial considerations, I can't say. If commercial considerations were the whole story, nobody would be playing jazz, but sometimes a thematic approach -- less tactfully, a gimmick -- may be a way to draw a little more attention to an artist, and sell a few more records.

Nothing wrong with that if, when you get down to making the music, you're there to play and nothing else. Which certainly seems to have been the case with Dave Pike. If you sign a recording contract at height of the bossa nova craze, and management says "Hey, how about a bossa nova album," you might do it just for the contract. That was the case when Bob Weinstock asked Annie Ross if she could write some songs to jazz solos--"I was desperate, so I said 'Sure.' If he'd asked me to learn how to fly, I would have said 'Sure.'" And the rest is history. Two of the greatests jazz vocalese pieces ever -- "Twisted" and "Farmer's Market." And Lambert, Hendricks and Ross. But it seems clear that Pike didn't do it just for the contract. Had that been the case, he wouldn't have chosen to feature the works of obscure (in the United States) composer Joao Donato.

Jazz interpretations of Broadway shows had shown some commercial appeal. Oliver! had been a hit in London, had been on tour in the United States, and was about to open on Broadway, where it would be a success, but would not really spawn any hit songs. "As Long as He Needs Me" had been a British hit for Shirley Bassey, and would later become a minor hit for Sammy Davis Jr. I'm not convinced that a jazz version of Oliver! was a surefire commercial bet in 1963, and I suspect one might not find all that many people today who could hum "As Long as He Needs Me," let alone the rest of the show. So I hope it was a project that really appealed to Pike.

A confluence of reasons--not a huge Oliver! fan base among the jazz crowd, the association of Pike with more out-there genres of music--have converged to make this a not widely remembered album. Also, when one thinks of the vibes in the context of the history of jazz, there's a bit of a temptation to enumerate Lionel Hampton and Milt Jackson and then stop. But there were a lot of very good players, and a lot of individual stylists, and several of them were on Prestige. Teddy Charles, back in the label's early days, who would give it all up to become a charter boat skipper. Lem Winchester, the jazz-playing cop, dead before his time. Walt Dickerson. And Dave Pike. Here, his work with Jimmy Raney and with Tommy Flanagan, two veterans who know how to challenge and support a young player, is well worth a listen.

Dave Pike Plays the Jazz Version of Oliver! is not represented on YouTube by any individual cuts, so I can't give a Listen to One, but the whole album is there, and worth checking out.

Don Schlitten, new to Prestige, produced. Schlitten had started an independent label, Signal, in 1955, then moved on to freelance producing after he and his partners sold the label to Savoy.

Dave Pike played the jazz version of "As Long as He Needs Me" for a 45 RPM single, with "Where is Love?" as the B side. The album was released on Moodsville.

Pike's next two albums, for Decca and Atlantic, are notable for introducing Chick Corea on the first, and employing the still-new Herbie Hancock on the second.

.jpg)