Reliving these jazz years through Prestige recording sessions is living in a dual reality. Part of you knows full well that you're looking back in time through the lens of age and distance, remembering your youthful excitement, appreciating the artists, and the recordings, that a perspective only brought by time and experience. But part of you is back then, 20 again, hearing the new sound from Symphony Sid or Ed Beach or Speed Anderson or Chuck Niles, buying the new album at Sam Goody's (or the 45 at Sam Goody's Annex), thinking that was solid, Jackson...what comes next?

But that flight of imagination comes to a crashing halt with Lem Winchester. Because you've known, from the moment he burst on the scene the year before, that this was going to happen. Each of his sessions feels, to the contemporary listener following this chronology, like sands through a very small hourglass. It feels that way when we listen to Eric Dolphy, who's also just arrived on the scene with Prestige, and Booker Little, who would make his Prestige debut shortly. And with Lem Winchester, for whom the sands are running out. This was his last session as leader; he would appear in a week with Johnny "Hammond" Smith, and then no more. In January the ex-cop would be dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, reportedly showing off a trick where you pretend to play Russian Roulette.

Winchester went out casual but tasty. No fireworks here. instead a quartet session of ballads intended for the Moodsville label. But they're all good tunes, and each one of them gets a swinging treatment, with lots of improvisational delights, and especially the pleasure of hearing some wonderful interplay between Winchester and Richard Wyands, where ideas are begun on piano and brought to fruition on vibes, or vice versa. This is Wyands' only recording gig in a group led by Winchester (he had joined Lem on an Oliver Nelson session), but they have a strong connection.

There's one Winchester original ("The Kids"). The rest are a mix of standards and current pop tunes. "Why Don't They Understand" was a 1957 hit, recorded by country singers as well as pop. Winchester's is the only known jazz interpretation. "To Love and Be Loved" is the Academy Award-nominated theme song from the 1958 movie Some Came Running, again not widely added to the repertoire of jazz musicians. It's a good mix. We may not have the same recognition for late 1950s pop hits that they received at the time (had they only thought of posterity, they might have taken on "Blue Suede Shoes" and "Sh-Boom" instead). but they still make for some very tasty jazz in the hands of Winchester and cohorts. And it's always a pleasure to hear a great jazz group's interpretation of beloved standards.

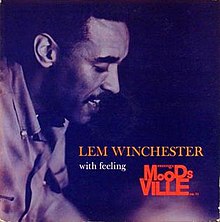

Esmond Edwards produced the session. The Moodsville release was titled Lem Winchester with Feeling.

Winchester got his start when a young trio, John Chowning's Collegiates, added him for a record date arranged by Chowning's father. The group planned to send the record to Leonard Feather as an audition for the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival. Feather passed on the group, but invited Winchester, then a Wilmington, Delaware police officer. Fifty years later, the three Collegiates reminisced about their sometme bandmate for the Current Research in Jazz website. Here's Chowning:

Winchester got his start when a young trio, John Chowning's Collegiates, added him for a record date arranged by Chowning's father. The group planned to send the record to Leonard Feather as an audition for the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival. Feather passed on the group, but invited Winchester, then a Wilmington, Delaware police officer. Fifty years later, the three Collegiates reminisced about their sometme bandmate for the Current Research in Jazz website. Here's Chowning:One can speculate whether Lem’s extraordinary talent would ever have been “noticed” at the level where it mattered if the recording had not been made. Perhaps not. Lem impressed us a man whose first love in music was the playing of it, not being a “name” in it. He had, we thought, more ambition for his notes than for himself.

At the time of the recording Lem was a successful officer in the Wilmington, Delaware, police force, assigned to what we now can call the African American community, where he was beloved by its inhabitants. The options for a smart and intelligent African American then were limited, especially one with a wife and young children. It was Lem’s mother, knowing that a police officer was at the pinnacle of power in her community, who persuaded him to join the police force in the first place. And she later was able to convince him to remain with the force, rather than joining his teenage friend and trumpet player, Clifford Brown, in the professional jazz scene.

...

To all of us Lem seemed content in a rewarding and stable career as a policeman — enriched by his stunning music on the side. He was revered by his community both as a police officer and by those who knew his music: he was welcomed into every musical setting he encountered.

In the spring or summer of 1958 my father, always our most unabashed supporter and spokesman, sent the LP to Leonard Feather... He was disappointed, I am sure, when the invitation came to Lem alone, but the three of us were not surprised. We were good enough players to recognize that Lem was a truly great jazz talent.

To my father’s credit, he maintained contact with Lem during the transition from police officer to professional jazz musician, and it was through him that the three of us learned of Lem’s tragic death in 1961.

George Lindamood

[I remember the first time Lem jammed with us. He] wore a gray sports jacket over his uniform so it would not be obvious that he was a policeman, but we kidded him about his regulation shirt, a shade of blue considerably darker than what was fashionable for business dress in those days. And then there was the bulge on his right hip that we knew to be his service revolver.

...a few weeks later...Lem had just finished one of his energetic solos and had lathered up a pretty good sweat in the process. When he took off his “plain clothes” jacket his police badge winked gold in the spotlight and the audience gasped in surprise... Without missing a beat, he laid the jacket on the piano top, unstrapped his holster and revolver, and dived back in for another chorus. The applause was at least fifty percent louder than before.

It often took me a couple hours to come down after a gig, so it was pointless to try to sleep. Often I borrowed John’s car, a well-worn brown Kaiser, and tracked Lem down where he was walking his midnight-to-dawn beat in one of the poorer sections of Wilmington. Lem did not seem to mind having a scrawny not-quite-19-year-old white kid tagging along in that all-black neighborhood, although occasionally he had me wait at a distance while he handled a difficult situation. Most of the time we just walked and talked, with him providing stories and advice from his perspective as a black man ten years older. It was a wonderful education for me.

And David Arnold:

The summer of 1957, our summer with Lem, was one of those years when the nation was in the throes of determining whether social tolerance would follow from the strengthening decisions that there must be legal tolerance.

It is within that context that I most easily place Lem. I remember his music, of course, but he comes striding with it out of that dark part of Wilmington, that dark part of national history, carrying the bright light of refutation. He was a good man. An unforgettable man.

As George has recalled above, we — who were the John Chowning Collegiates — had thrown open the doors of Marshalls Restaurants for Monday night jam sessions.

The Collegiates, a musically literate trio learning new things with every performance, played what we hoped was jazz — and very often it was. But with Lem and his group there was no question. Marshalls lit up like fireworks. We were hearing what jazz was all about. He might call his style “down home” (another bit of modesty in a way) but it swung with a rhythmic curl and driving force that threatened the walls of the place. On top of it all was Lem’s intricate cascade of notes, at times more than could possibly come from just two mallets, and at other times simply and quietly a delicate, laid-back, slightly off-the-beat sounding of simple melody played in octaves. Push hard and pull back.

Lem was uncommonly gentle and forgiving. And he had that best thing of the best in music: the desire to teach, to pass it on.

It is that last thing I remember most — that and his matter-of-fact and unforced tolerance. Of all the musicians in Marshalls on those nights, I was by far the most unaccomplished... Yet Lem took the time to help, to give me some ideas. He might have seen promise. Or he might have been kind.

...certainly we could see his gift to us: the benefit, like a windfall, of being fronted by a genius on the vibes. He was among the very best, had friends among the very best — Clifford Brown for one — and so how did we deserve him? I have never stopped wondering.

The recording tells the story. On Lem’s cuts his playing transforms us into a different group. He lifts and drives, lightens the load, inspires. There is promise for us all....

In the end we Collegiates had graduations and careers to think about. But for Lem the recording made all the difference. We were both disappointed and relieved when Leonard Feather’s Newport nod went to Lem and not the rest of us but, as John says, we knew who the star was.

... In January of 1961 Lem was on the road, a professional musician, commercial recordings to his credit. But he carried with him a relic of his policeman days: a trick with a revolver in which all bullets but one were removed from their chambers. Gun to his head, bar-sitters watching, he would pull the trigger and the hammer would click as the cylinder rotated to an empty chamber. But that night in Indianapolis he used a different gun. The cylinder rotated in the opposite direction.

John Chowning went on to an unheralded but significant career in music. He studied composition with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. Later, he discovered FM synthesis, "a very simple yet elegant way of creating time-varying spectra. Licensed by Stanford to Yamaha, FM synthesis led to a family of synthesizers (DX7) that became the most successful of all time."

Lem Winchester left a small but significant body of work. He touched lives both as a policeman and a musician.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-12201874-1530374993-9392.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-9099794-1474857968-5970.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-11364066-1516045515-2606.jpeg.jpg)