Harry Smith's seminal 6-LP collection, Anthology of American Folk Music, came out in 1952, and was an important spur to the folk music revival of the 1950s. Most of it was given to the folk music made by whites in Appalachia and other rural settings, but there were some blues as well: Charley Patton, Furry Lewis, Jim Jackson, Blind Willie Johnson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Sleepy John Estes and a couple of others.

Samuel Charters' now-classic study, The Country Blues, was published in 1959, but there were few ways to hear very much country blues. Folkways put out an LP companion to Charters' book.

Son House, who had played with Patton and was still alive, would not be rediscovered until 1964, although he wasn't hard to find. He was living in Rochester, New York, and he was re-introduced to the new and still tiny audience for traditional blues in coffee houses and at festivals --folk festivals. There were no blues festivals until the Ann Arbor Blues Festival in 1969 (at which Son House was one of the performers).

Folkways recorded a few blues singers: Lead Belly, Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee--the ones who had migrated to New York. Urban leftists had adopted folk music as a people's music, and the blues to a lesser extent. The problem with the blues was that it was rarely a music of political protest. The blues was a music of intense realism--life was hard, and it was going to stay that way. Triumphs--sexual conquest, getting drunk, killing a rival--were fleeting. The leftists wanted to believe that the world could be changed and made a better place. Lead Belly did what people who sing for their supper had always done. He adapted. He started writing songs about not wanting to be mistreated by no bourgeoisie. But musicians already in their graves, like Patton and Jefferson and Johnson, would be writing no new songs.

The blues singers who had migrated to the Midwest, to Chicago and Detroit, were creating a new kind of blues, and a few performers like Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Fats Domino were finding ways to take that music to a larger audience, but of course no one called that the blues any more.

The white imitators of traditional bluesmen, like John Hammond Jr. and Koerner, Ray and Glover, were still a couple of years out on the horizon, and the white imitators of Chicago blues, mostly from Britain, were a couple of years behind them.

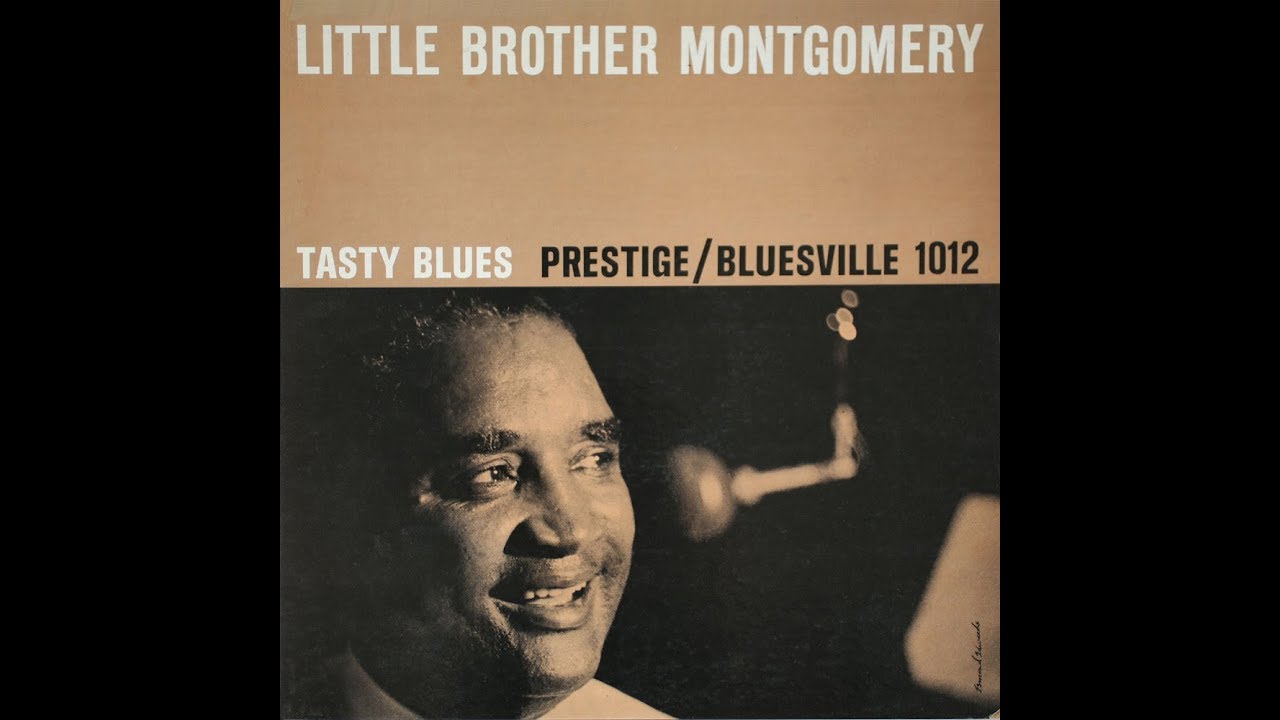

So what this adds up to is very little demand for a Little Brother Montgomery album, as seems to have been the case with so many of the Bluesville releases. Columbia Records may have thought they were in the vanguard of a new craze when they released King of the Delta Blues Singers, the first Robert Johnson compilation. The title suggests it, and Columbia's big-budget promotion department suggests it. But Weinstock probably had no such grand notions. To whatever extent he was motivated to start Bluesville and Swingville by bookkeeping and tax considerations, he seems to have really wanted to get some interesting blues out there, with the Prestige touch.

The Prestige touch was engineering by Rudy Van Gelder, and often some very fine contemporary jazz musicians, as was the case here, with Julian Euell on bass.

The very interesting blues musician was Little Brother Montgomery. Born in 1906 in Louisiana, where Jelly Roll Morton was a family friend, he made his first record in 1930 for Paramount, itself an interesting story.

Paramount Records was founded in 1917 by a company in Wisconsin that made chairs, and had begun making wooden phonographs. Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, but he did not originally think of it as device for recording and playing music. Phonograph records did not come along until a number of years, which makes sense. You have to have the hardware before you worry about software. But since phonographs were originally marketed as upscale pieces of furniture, it makes sense that a furniture company should go into the record business, and that phonograph records were originally sold in furniture stores.

Montgomery recorded "Vicksburg Blues" for Paramount. It became his signature song. He continued to record sporadically through the 1930s, mostly for Bluebird.

Three things happened to the musicians of his generation. They died young, like Charley Patton and Robert Johnson. They dropped out, like Son House. Some of them, like House, were rediscovered during the blues craze of the 1960s, others never resurfaced. Or, like Little Brother Montgomery, they hung on. They moved north, to Chicago or Detroit or Los Angeles, or even places like Cincinnati, home of King Records. Not as many as you'd think to New York. They found places to play, mostly the new amplified blues that would eventually make stars out of Mississippi emigrants like Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf. Montgomery had a successful five-piece band at a Chicago club, the Club Hollywood, for twelve years.

Montgomery signed on in the 1950s with Ebony Records, a tiny independent and one of the few black-owned labels of the era. Ebony and a handful of other labels had been started in New York by J. Mayo Williams, composer of "Corinna Corinna" and "Fine Brown Frame," who would later move it to Chicago. Williams was one of the first to record Etta Jones, on his Chicago label (out of New York). He recorded a few sides throughout the 1950s with Ebony, but the label had almost no distribution. He also made some recordings with Sunnyland Slim.

But although he had stayed active, and stayed employed, he was pretty much an unknown when Prestige signed him up for this recording, with Euell on bass and Lafayette Thomas, a West Coast guitar player (though he had recorded, with fellow Californian Jimmy McCracklin, for Chess) who was temporarily living and working in New York. Thomas had previously worked on the Memphis Slim session in April.

So although Little Brother Montgomery could be found, if one looked really hard, on 45 RPM records, and he would go on to make several more LPs for Folkways, this was an important recording, and an important step in the documentation of the blues. Frank Driggs, in his liner notes, says that Montgomery "has always refused to buckle under to the rock and roll, rhythm and blues trend" (displaying the anti-rhythm-and-blues bias that was so universal at the time in the jazz world), "despite many offers to take out rock and roll bands." Well, there were a lot of great rhythm and blues bands throughout the 1940s and 50s, but not too many who carried on that Leroy Carr tradition of piano blues.

This is a lovely selection of traditional blues, including a couple of his most tried and true numbers. He has sung "Vicksburg Blues" many times over four decades--hell, he's recorded it many times--and he's developed some nifty variations to the piano part. "No Special Rider" is another of his old favorites, and "Satellite Blues" applies some classic blues styling to a very contemporary subject. The Russians had beaten the USA to outer space in 1957 with Sputnik, and had sent a dog into outer space the same year (Muttnik). Sputnik II burned up before it could return to earth, and still today, with my little Sydney curled up beside me as I write this, I can't help but think of poor Laika, alone and doomed in that early spacecraft. In 1959, the USA sent up two monkeys and retrieved them alive, and it's those two monkeys that Montgomery asks to serve as his proxy, looking for his woman who has left him so utterly and completely that she must have gone into outer space. Montgomery pays tribute to Leroy Carr with an instrumental version of "How Long Blues," here called "How Long, Brother."

Bluesville released the album as Tasty Blues.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4833263-1378615338-2710.jpeg.jpg)

.jpg/220px-Soul_Sister_(album).jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-2792942-1301254465.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-9902795-1488234131-6616.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-3510867-1344545965-4983.jpeg.jpg)