The behatted tenor man was blowing at the peak of a wonderfully satisfactory free idea, a rising and falling riff that went from “EE-yah!” to a crazier “EE-de-lee-yah!” and blasted along to the rolling crash of butt-scarred drums hammered by a big brutal Negro with a bullneck who didn’t give a damn about anything but punishing his busted tubs, crash, rattle-ti-boom, crash. Uproars of music and the tenor man had it and everybody knew he had it. Dean was clutching his head in the crowd, and it was a mad crowd. They were all urging that tenor man to hold it and keep it with cries and wild eyes, and he was raising himself from a crouch and going down again with his horn, looping it up in a clear cry above the furor...What were Sal and Dean listening to? This was 1947, around the time that Charlie Parker and his new music had failed to conquer the hearts and minds of LA audiences, and there wasn’t going to be much of a modern jazz scene in Oakland. They had most likely wandered into a club featuring a tenor man who taken the ideas and tonality of Lester Young, plus the new honking sound of Illinois Jacquet, and added a few helpings of Dionysian excess to create a kind of jazz that a club audience on Saturday night could respond to primally: a tenor man like Big Jay McNeely or Willis “Gator Tail” Jackson.

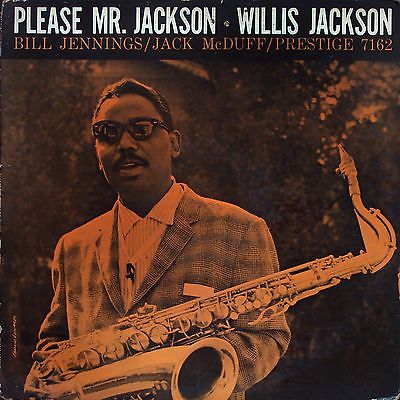

By the time Jackson signed on with Prestige in 1959, at age 27, he had already packed a lot of playing into his life. As a teenager, he turned down offers from Lionel Hampton and Andy Kirk to finish college, which is something to add to your stereotype of what a tenor sax wild man is like. After graduating from Florida A&M, he joined Cootie Williams in time to play the tenor solo on Williams’s jukebox hit “Gator Tail,” which functioned in his career in much the same way “Flying Home” had done for Illinois Jacquet and Arnett Cobb, plus it gave him the nickname he would carry with him for the rest of his life.

After Williams, he led his own popular groups, and worked with Ruth Brown at Atlantic. He had played on her mega-hit “5-10-15 Hours,” and they would spend part of the decade as husband and wife. But as the 1950s wound down, the honking dynamic tenor sax that been a staple of the rhythm and blues of the 1940s and 50s was waning in popularity, just as the new sound of soul jazz was waking up. Fortunately, someone at Prestige, perhaps Esmond Edwards, figured out that if you were looking for a guy who who could play down and dirty and could also play modern, there was a treasure trove of guys who could do it and had been doing it for a while, including at least one who had heard the siren song of the tenor sax/organ combo. Fortunately for the Gator, whose career was rejuvenated, and fortunately for Prestige, which got not one but three of its stars of the coming decade; Jackson himself, guitarist Bill Jennings, and organist Jack McDuff.

McDuff had joined Jackson’s band as a bassist, and it was the Gator who convinced him to switch to organ, an instrument he took to the way the Smith Brothers took to cough drops. So when Prestige came calling, Jackson already had just the group they were looking for.

Bill Jennings never amassed the kind of discography that Jack McDuff did. He was one of those “musicians’ musicians,” largely overlooked during his career, reclaimed—and claimed—by guitarists who followed him. B. B. King called him:

A daring player, both rhythmically and technically... because he would start a groove to going, and then whatever it takes to keep that groove going, he would do it.Tommy Potter, one of mainstays of the bass during the early bebop era, was pretty close to the end of his career--his work on this Jackson session may be his last on record. Alvin Johnson was part of the group Jackson brought with him to Prestige, and isn't know for much beyond his work with Jackson, McDuff and Jennings, but he knew how to keep things going.

This is an immense session. Maybe Edwards wasn't sure he was going to be able to keep Jackson, McDuff and Jennings around (he needn't have worried), or maybe everyone was just having a good time. In any event, the fourteen tunes cut on this date showed up on three immediate releases, and many more over time.

Jackson and co. mix standards and originals, honkers and ballads, something for everyone.

I don’t think I was much of a fan of organ combos back when. I may have bought a Jimmy Smith album sometime in the 60s, but like many, I was a little put off by organ music, the sound of church and roller rink and radio soap operas. I don't really know of another instrument that arouses such negativity in so many listeners. Maybe bagpipes, except for Philadelphia's Rufus Harley, there isn't much of a bagpipe presence in jazz. So I can add one more to the delights of listening carefully and closely to everything recorded for Prestige Records: really coming to understand and appreciate the range and tonality of the Hammond B3 organ in the hands of some jazz virtuosos, and to appreciate how the B3 and the tenor saxophone were, in fact, made for each other.

Please Mr. Jackson, released in 1959, was the first from this session. It was followed by Cool "Gator" in 1960. "Gator's Tail" and "She's Funny That Way" were held back for a second 1960 release, Blue Gator. The three 45 RPM records to come from this session were "Please Mr. Jackson" / "Dinky's Mood," "Come Back To Sorrento" / "On the Sunny Side of the Street," and "Cool Grits, Part 1 & 2."

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-2155184-1465994640-9082.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5593602-1397494876-9749.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3994398-1351709445-8958.jpeg.jpg)