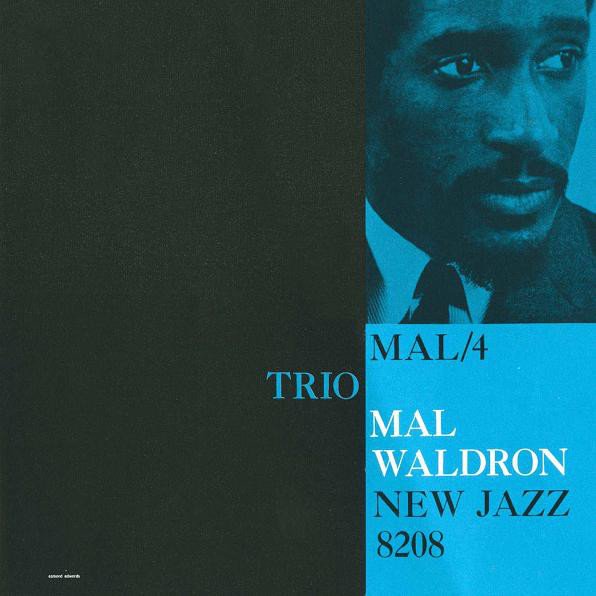

This one is particularly noteworthy for two things. First, his quartet personnel has changed. Buell Neidlinger returns as bassist, Elvin Jones is the new drummer. Most significantly, he is put together with the Prestige "house pianist," Mal Waldron, a pairing that was to be of great significance to both men when they reconnected years later in Europe.

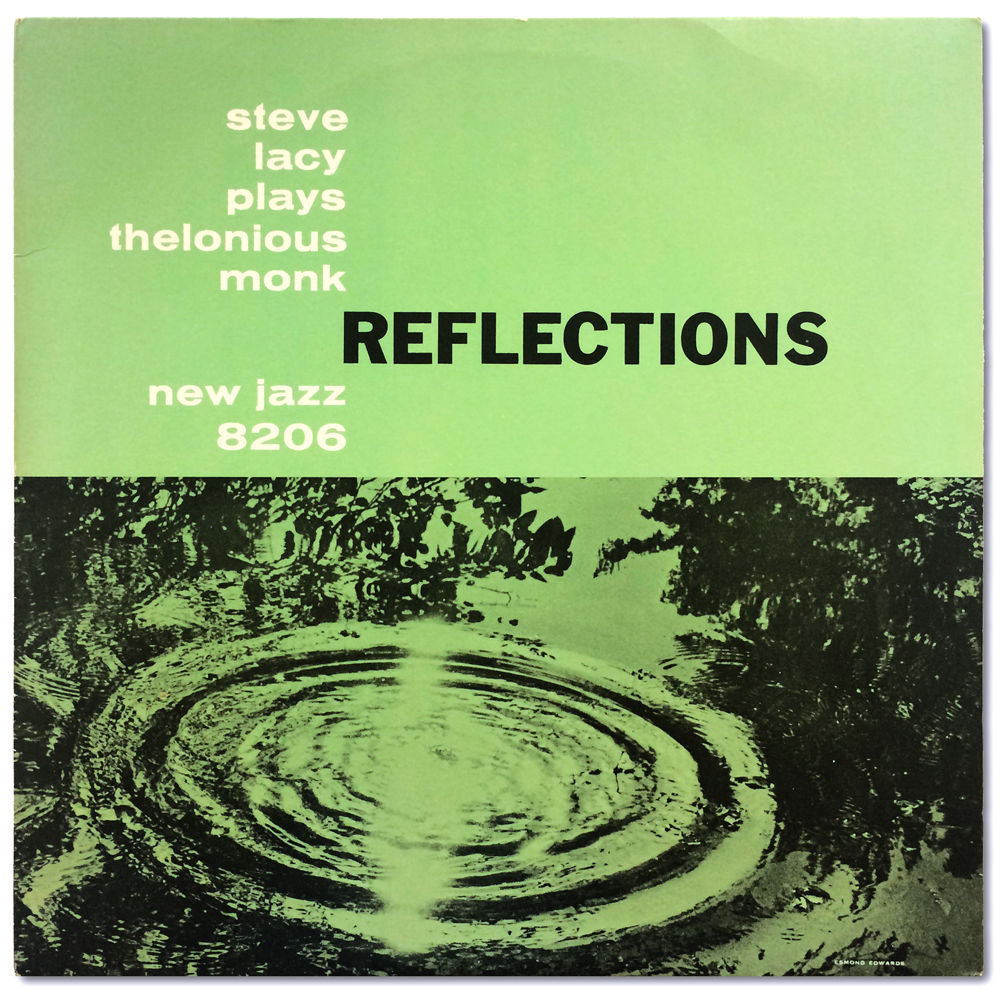

Second, the entire album is devoted to the compositions of Thelonious Monk. Lacy was an admirer and champion of Monk's work, and tried to include at least one Monk composition on every recording he made, but this is the first time an entire album has been devoted to this great composer's work.

It's an article of faith among many, myself included, that Thelonious Monk and Duke Ellington are good candidates for the two most important 20th Century American composers, but that awareness has been slower in coming than you might think. Sure, "Round Midnight" became an instant classic, and so did several of his other works, but Lacy dug deeper into the catalog, and found pieces for which recognition came much slower, if at all.

Secondhandsongs.com is a fascinating website which tracks the cover versions of songs. It doesn't list every song ever composed, though they keep adding to it, and there's no guarantee they're going to catch every cover, but they are a wonderful resource. Here's what they have on the tunes from this album:

- Hornin' In: Recorded for Blue Note in 1952 and released in 1956. After Lacy's version, no one paid attention to this tune for 40 years, until Sonny Fortune in 1994. Since then, very little. Sphere, the group founded after Monk's death and devoted to his music, recorded it, as did two European jazz groups, and that's it, except for an unusual interpretation by rockers Terry Adams and NRBQ in 2015. YouTube offers a couple more recent live versions, and there is no reason why this wonderful piece of music should not be a jazz standard except that it's in competition with so many other classics from this composer.

- Skippy was recorded by Monk in 1952 for Blue Note, and seems to have only been released on a 78 RPM single. It's complex, stirring, uptempo. Lacy's version features a terrific solo by Mal Waldron, among other delights. Lacy recorded it once more two decades later with a different quartet (Roswell Rudd, Henry Grimes, Dennis Charles), and then it lay fallow until 1988, when Buell Neidlinger recorded his own version, and Anthony Braxton covered it. In 1994 it was picked up by Paul Motian among others, and this millennium it's been rediscovered by a number of young jazz esnembles, both European and American, to the point where it can legitimately be called a standard. But 'twas not always thus.

Monk's own version features Kenny Dorham, Lou Donaldson and Lucky Thompson, from the same session that produced "Hornin' In." - Reflections is Steve Lacy's title cut. It is an absolutely beautiful melody, from an early Prestige trio session. It captures both Lacy and Waldron at their most lyrical. Monk was an important influence on Waldron, but not an early influence. Certainly this session with Lacy must have affected him deeply.

"Reflections" is certainly a standard, covered four times as often as Holland-Dozier-Holland's same-titled song for the Supremes.. J. J. and Kai (Savoy) and Sonny Rollins (Blue Note) both recorded it before Lacy. But then it also was pretty much forgotten until 1982, when Chick Corea, Miroslav Vitous and Roy Haynes did it. Since then, it's become ubiquitous, with secondhandsongs listing 66 versions. But a tune this important in the monk canon went a long time ignored. - Monk's version of Four in One (Sahib Shihab, Milt Jackson, Al McKibbon, Max Roach) was released by Blue Note in 1952 on 78 and on the Genius of Modern Music, Vol. 2 album. Lacy's version features some driving Elvin Jones work along with the solos by Lacy and Waldron. Then again, a long period of neglect. Monk's death in 1982 brought about a renewed interest in his music, and one of the first stirrings of this was a very odd album in 1984, That's the Way I Feel Now, a tribute to Monk by an eclectic bunch of musicians, most of them rockers. "Four in One" was covered by Gary Windo, a British avant-gardist who played his own brand of music, more often lending it to rock than jazz performers, and Todd Rundgren. Windo played alto sax, Rundgren supplied synthesizers and drum machines, for a performance that's manic, chaotic, geared to a rock-steady beat, and still recognizable as Monk.

Since then, it too has entered the Monk mainstream, with 33 versions listed by secondhandsongs. - Bye-Ya is one of the pieces that Monk and Coltrane performed on their 1957 Carnegie Hall concert, a recording of which was only recently rediscovered and released. It's such a familiar tune that it seems impossible that it, too, could have languished throughout the 1960s and 1970s, but it did. This started to make me curious, and I checked secondhandsongs for some of Monk's best-known compositions, starting, of course, with "Round Midnight." Composed in 1940, first recorded by Cootie Williams (who took co-composer credit), it became an instant classic when Blue Note released Genius of Modern Music, Volume 1 in 1951. Since 1955, scarcely a year has gone by without several recorded renditions of it. "Blue Monk," first released on Prestige in 1954, has proved nearly as popular, with "Straight No Chaser" and "Ruby, My Dear" not far behind. So at least Monk was getting royalties from some of his classics during his lifetime. "Bye-Ya" has five lifetime, 48 posthumous, and secondhandsongs has somehow missed the Carnegie Hall concert.

- Ask Me Now has had a similar fate. Steve Lacy, PeeWee Russell and Ronnie Mathews during Monk's lifetime, 91 posthumous versions.

Secondhandsongs doesn't have information on "Let's Call This."

Reflections was released on New Jazz in 1959.

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 2

Reflections was released on New Jazz in 1959.

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 2

Listening to Prestige Vol. 2, 1954-1956 is here! You can order your signed copy or copies through the link above.

Tad Richards will strike a nerve with all of us who were privileged to have lived thru the beginnings of bebop, and with those who have since fallen under the spell of this American phenomenon…a one-of-a-kind reference book, that will surely take its place in the history of this music.

--Dave Grusin

An important reference book of all the Prestige recordings during the time period. Furthermore, Each song chosen is a brilliant representation of the artist which leaves the listener free to explore further. The stories behind the making of each track are incredibly informative and give a glimpse deeper into the artists at work.

--Murali Coryell

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-9006076-1473149580-5385.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-10297492-1494867502-9568.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7306051-1438474214-6531.jpeg.jpg)