Here's a quick rundown of his post-Miles oeuvre with Prestige, up to this current session.

- Elmo Hope All Star Sextet, May 7, 1956. This was actually issued two different ways, at the same time and with the same catalog number, but with two different covers and two different billings: as Elmo Hope - Informal Jazz and as Hank Mobley/John Coltrane - Two Tenors. He would finally get top billing in a 1969 re-release: John Coltrane - 2 Tenors With Hank Mobley. Wikipedia's entry on the 1969 release comments: "As Coltrane's fame grew during the 1960s long after he had stopped recording for the label, Prestige assembled varied recordings, often those where Coltrane had been merely a sideman, and reissued them as a new album with Coltrane's name prominently displayed." But "merely a sideman" only describes the billing on the album cover. In a quintet or sextet album of jazz masters, there's no merely. Everyone contributes.

- Sonny Rollins Quartet With John Coltrane, May 24, 1956. Trane gets featured billing on the session notes, not on the album cover. There it's Sonny Rollins - Tenor Madness, and on the reissue, Sonny Rollins - Taking Care of Business. But there's a reason for this. The title cut, "Tenor Madness," is an epic duet -- the only one between these two tenor legends. But it's also Coltrane's only cut on the session.

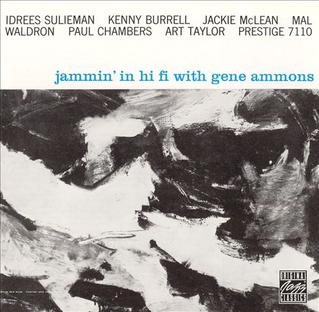

- The Prestige All Stars, September 7, 1956. I don't think any of the Prestige All Stars sessions were actually packaged as "Prestige All Stars." Generally, the album cover had the whole cast, sometimes omitting the rhythm section, with each musician getting equal billing. Such was the case here. This was two of the original Four Brothers, Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, with two new brothers, Coltrane and Hank Mobley. The album was titled Tenor Conclave, and listed the brothers (Mobley - Cohn - Coltrane - Sims) on the cover. The order isn't alphabetical, and it isn't by seniority. Maybe they just flipped a coin. Two later reissues were under Coltrane's name, the first keeping Tenor Conclave and the second including a Tadd Dameron session and titled On a Misty Night.

- Tadd Dameron Quartet, November 30, 1956. Booked as a Dameron session. there was co-billing on the album cover: Tadd Dameron/John Coltrane - Mating Call. It would be rereleased as On a Misty Night, under Trane's name alone, and the "On a Misty Night" track would also be put on another Trane repackage, John Coltrane Plays For Lovers --misnamed, if you ask Tom Cruise. In Jerry Maguire, Cruise's friend gives him a Miles Davis and John Coltrane tape to play during lovemaking, but when the moment comes, Cruise listens to a few bars, says "What is this shit?" and throws it out.

- The Prestige All Stars, March 22, 1957. Released as Interplay For 2 Trumpets And 2 Tenors, with the usual equal billing for all musicians. The two trumpets were Idrees Sulieman and Webster Young, the two tenors were Trane and Bobby Jaspar. This was reissued as Jazz Interplay, but never got a reisssue under Coltrane's name.

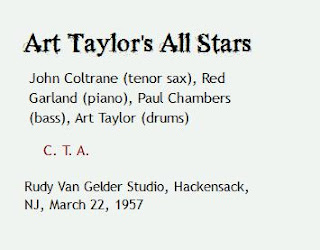

- Art Taylor's All Stars. March 22, 1957. One cut, from the same date, this one a quartet with Taylor, Coltrane, Red Garland and Paul Chambers, for inclusion on a different Taylor session that didn't quite fill out an album.

- The Prestige All Stars, April, 1957. Just the day before the current session, and released as Tommy Flanagan / John Coltrane / Kenny Burrell.

Up to this point, no sessions with Coltrane as leader, although that will come, and a marvelous potpourri of musicians.

I basically approve of the democratic approach to billing on the All Stars sessions, and as stated above, I take issue with the Wiki writer's "merely a sideman." None of the were merely anything. And I suspect this is an echo of the condescension contemporary writers show toward Prestige -- in a addition to sloppy and unrehearsed, Weinstock's label is also put down for the frequency of its repackagings. You know how I feel about all of these criticisms. The hell with them.

And speaking of marvelous potpourris, the tune that Mal Waldron wrote for an earlier session with Thad Jones, Frank Wess and Teddy Charles makes its reappearance here.

"Potpourri" is pure bebop, and surely one of the reasons why bebop retains its vitality well into the 1950s is the emergence of composers like Waldron,

The other Waldron originals: "J. M.'s Dream Doll," and that must have been some dream, or some doll. Some great solos here, but Waldron's is really outstanding. And "Blue Calypso." Remember the

mambo bebop craze of a couple of years back, with Joe Holiday and Billy Taylor as its champions, but also contributions from James Moody, Sonny Rollins, Sonny Stitt, Kenny Graham (mambo bebop from England!). Well, it turns out you can do it with calypso, too. Sonnny Rollins, from island-born parents, would make calypso his own, but here in 1957, with Harry Belafonte topping the charts with one of the most popular albums of all time, Waldron, Coltrane et al. show how its rhythms can be assimilated into the language of bop.

"Don't Explain" was written by Billie Holiday and her frequent collaborator Arthur Herzog, Jr., and covering a song associated with Billie inevitably means finding a correlative to the intensity of feeling that she put into everything. "Falling in Love with Love" is by Rodgers and Hart, and nothing Lorenz Hart wrote was entirely sentimental, but this song is often given a sentimental treatment by crooners. Not here.

"Potpourri," "J. M.'s Dream Doll" and "Don't Explain became part of Waldron's Mal-2 album, Mal-2, released in 1957. "Blue Calypso" and "Falling in Love With Love" had something of an odder fate. In spite of whatever sales potential a calypso may have had in 1957, both were left off and not released until 1964--and then only on the short-lived Prestige subsidiary Status, which was definitely a budget label, pressed on cheaper quality vinyl and marketed straight to the budget bins. That album, which put together outtakes from two Waldron sessions, was called The Dealers. The session was ultimately released under Coltrane's name in a much later CD box called Side Steps, a title which suggests "like Giant Steps but less important." Well, maybe so. Very few things touch Giant Steps. But great stuff nonetheless.

"Potpourri," "J. M.'s Dream Doll" and "Don't Explain became part of Waldron's Mal-2 album, Mal-2, released in 1957. "Blue Calypso" and "Falling in Love With Love" had something of an odder fate. In spite of whatever sales potential a calypso may have had in 1957, both were left off and not released until 1964--and then only on the short-lived Prestige subsidiary Status, which was definitely a budget label, pressed on cheaper quality vinyl and marketed straight to the budget bins. That album, which put together outtakes from two Waldron sessions, was called The Dealers. The session was ultimately released under Coltrane's name in a much later CD box called Side Steps, a title which suggests "like Giant Steps but less important." Well, maybe so. Very few things touch Giant Steps. But great stuff nonetheless.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

"Potpourri" is pure bebop, and surely one of the reasons why bebop retains its vitality well into the 1950s is the emergence of composers like Waldron,

The other Waldron originals: "J. M.'s Dream Doll," and that must have been some dream, or some doll. Some great solos here, but Waldron's is really outstanding. And "Blue Calypso." Remember the

mambo bebop craze of a couple of years back, with Joe Holiday and Billy Taylor as its champions, but also contributions from James Moody, Sonny Rollins, Sonny Stitt, Kenny Graham (mambo bebop from England!). Well, it turns out you can do it with calypso, too. Sonnny Rollins, from island-born parents, would make calypso his own, but here in 1957, with Harry Belafonte topping the charts with one of the most popular albums of all time, Waldron, Coltrane et al. show how its rhythms can be assimilated into the language of bop.

"Don't Explain" was written by Billie Holiday and her frequent collaborator Arthur Herzog, Jr., and covering a song associated with Billie inevitably means finding a correlative to the intensity of feeling that she put into everything. "Falling in Love with Love" is by Rodgers and Hart, and nothing Lorenz Hart wrote was entirely sentimental, but this song is often given a sentimental treatment by crooners. Not here.

"Potpourri," "J. M.'s Dream Doll" and "Don't Explain became part of Waldron's Mal-2 album, Mal-2, released in 1957. "Blue Calypso" and "Falling in Love With Love" had something of an odder fate. In spite of whatever sales potential a calypso may have had in 1957, both were left off and not released until 1964--and then only on the short-lived Prestige subsidiary Status, which was definitely a budget label, pressed on cheaper quality vinyl and marketed straight to the budget bins. That album, which put together outtakes from two Waldron sessions, was called The Dealers. The session was ultimately released under Coltrane's name in a much later CD box called Side Steps, a title which suggests "like Giant Steps but less important." Well, maybe so. Very few things touch Giant Steps. But great stuff nonetheless.

"Potpourri," "J. M.'s Dream Doll" and "Don't Explain became part of Waldron's Mal-2 album, Mal-2, released in 1957. "Blue Calypso" and "Falling in Love With Love" had something of an odder fate. In spite of whatever sales potential a calypso may have had in 1957, both were left off and not released until 1964--and then only on the short-lived Prestige subsidiary Status, which was definitely a budget label, pressed on cheaper quality vinyl and marketed straight to the budget bins. That album, which put together outtakes from two Waldron sessions, was called The Dealers. The session was ultimately released under Coltrane's name in a much later CD box called Side Steps, a title which suggests "like Giant Steps but less important." Well, maybe so. Very few things touch Giant Steps. But great stuff nonetheless.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5494600-1394834078-9299.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3559105-1335246182.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3160372-1318517568.jpeg.jpg)

.jpeg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-885829-1169223198.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2438609-1435452530-5422.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-3675099-1339881223-1063.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5512017-1395271608-8116.jpeg.jpg)