Not sure how this differs from other sessions. Did they tell Hank Mobley, "Hey, we want you to put together a combo for a recording session this week -- oh, but you'll be using Watkins and Taylor"? Or maybe these were all basically Prestige All Stars sessions, but only now did they decide to call it that. Presumably the leader would bring in the tunes, or most of them. In this nominally leaderless session, they included a tune that was composed by a contemporary jazzer who's not on the session: Kenny Drew's "Contour." Probably Jackie McLean brought it in--he had an affinity for the tune, had played it just recently on one of his 4, 5 and 6 dates (Donald Byrd was on that session, too). In any event, it's a fine tune, and more people should record it, and actually, several have.

Certainly, McLean must have brought "Dig" to the session, given that it's his composition, even though Miles grabbed the composer credit for it, and whatever royalties it accrued, but this is jazz, so there probably weren't many, as McLean was told when he looked into suing Miles -- it wouldn't be worth it.

"The Third" is a Donald Byrd composition, so one figures he brought it in. He probably also brought "'Round Midnight," since he's the only horn on that track. Art Farmer takes "When Your Lover Has Gone" on his own, so it's likely his choice.

"Dig" is the centerpiece of the album, at nearly 15 minutes. I was interested to see how it compared to the version that was laid down the day Jackie first brought it into the studio to record with Miles and Sonny Rollins. The Davis-Rollins-McLean version is more melodic, the Prestige All Stars more intense--and at this length, that intensity has to be sustained, and it is. All the soloists are powerful. I started to try to name a favorite, but I can't.

However far afield an improvisation goes, if there's going to be enough meat to sustain it for 15 minutes, it's got to be a very good tune to start with, and "Dig" is. I'm surprised it hasn't been covered more often.

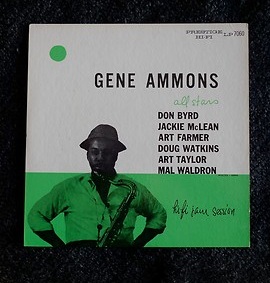

When the album was actually pressed and given a cover and released, it was called 2 Trumpets and credited to Farmer and Byrd. A rerelease was again Farmer and Byrd, and called Trumpets All Out, and a much much later rerelease just had Byrd's name above the title, which was House of Byrd.