Maybe Bennie Green never got his due. One website that makes lists and rankings puts him at #31 on its list of greatest jazz trombonists of all time (Bill Harris, who won several DownBeat polls in the early 50s, is #32). A site called The Trombone Forum has a discussion of the greatest jazz trombone recordings of all time, and Bennie Green is not mentioned by anyone.

This is just wrong. But even so, if you were inspired by my earlier praise, and decided to pick up a Bennie Green album. you probably wouldn't choose this one. You might go for the earlier 1956 session with Art Farmer and Philly Joe Jones. Or the one from 1955 with Charlie Rouse and Paul Chambers, or the one that added Candido to that mix. Or you might go back to 1951 and the session with Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis, Art Blakey and Tommy Potter.

In short, faced with a blind choice of which record to take a chance on, you'd go with the chalk--the sidemen you've heard of.

Don't do it. Well, do it. Those are all terrific albums. But don't overlook this one with the sidemen you've probably never heard of.

Look at it this way. For Blakey or Farmer or even a brand new cat on the scene, 19-year-old Paul Chambers, this was another gig. For these guys, it may well have seemed the opportunity of a lifetime--a small group session on Prestige!

I don't mean that these weren't highly respected professionals. Green didn't pull them out of thin air.

Eric Dixon was 26 when this session went down, and he had a long and productive career ahead of him. He went on to appear, by some counts, on over 200 recordings, including some other small group sessions for Prestige/New Jazz in the 60s: Ahmed Abdul-Malik, Kenny Burrell, Etta Jones and Mal Waldron. But his main gig starting around the turn of the decade and going on for two more decades, including many recordings, was with the Count Basie orchestra. His one record as leader came in 1974, for the Master Jazz Recordings label, and featured both Lloyd Mayers and Bill English.

Eric Dixon was 26 when this session went down, and he had a long and productive career ahead of him. He went on to appear, by some counts, on over 200 recordings, including some other small group sessions for Prestige/New Jazz in the 60s: Ahmed Abdul-Malik, Kenny Burrell, Etta Jones and Mal Waldron. But his main gig starting around the turn of the decade and going on for two more decades, including many recordings, was with the Count Basie orchestra. His one record as leader came in 1974, for the Master Jazz Recordings label, and featured both Lloyd Mayers and Bill English.Lloyd Mayers recorded in the 60s, with Lou Donaldson, Betty Carter, Ray Barretto and others. but his big break didn't come until 1974--and no, it wasn't the Eric Dixon album. Mercer Ellington tapped him to fill the Duke's shoes in the Ellington orchestra. He was musical director for the 1981 Broadway production of Sophisticated Ladies, the musical based on Duke's music.

Sonny Wellesley and Bill English don't have the same extensive pedigrees. Wellesley played on a Blue Note session with Ike Quebec, recorded in 1959, a couple of the tunes released on 45, not released in album form till until 2000. He seems to have played in 1961 with Sir Charles Thompson, but they may not have recorded. I can't find any reference to a record.

Bill English (not be confused with Willie Nelson's drummer Billy English) made one record as leader, for Vanguard, which was primarily a folk label, and probably didn't do much to promote its occasional jazz titles. The jazz collectibles website popsike.com lists it for sale under the heading "Obscure jazz drummer Bill English." Lloyd Mayers played on this one, too. Obscure or no, you can find it on both YouTube and Spotify, and it's good stuff.

So perhaps these guys were playing together when Green tapped them, since they certainly seem to have stayed in touch afterwards. They're tight and simpatico on this session.

So if this was an audition for a big time career, they all passed with flying colors--even if, as with today's law school grads and creative writing MFA's, they didn't all get much professional advancement out of it.

The session starts with "Walkin' (Down)," which is better known without the "(Down)" as the Miles Davis classic. "Walkin'" is credited to Richard Carpenter--not the songwriter with the talented sister. This Richard Carpenter was a gonef perhaps rivaled only by Mo Levy, best known for buying songs from hard-up musicians for 25 or 50 dollars and slapping his own name on them. Sometimes he didn't even buy them. When composer-arranger Jimmy Mundy, best known for his work with the Goodman and Basie bands, died in 1983, a copyright certificate was found at the Library of Congress for a tune called "Gravey." The title, and Mundy's name, had been incompletely erased, and "Walkin'" by Richard Carpenter written over them. Junior Mance, who was with him at the time, has also confirmed that Mundy wrote the song and titled it "Gravey."

|

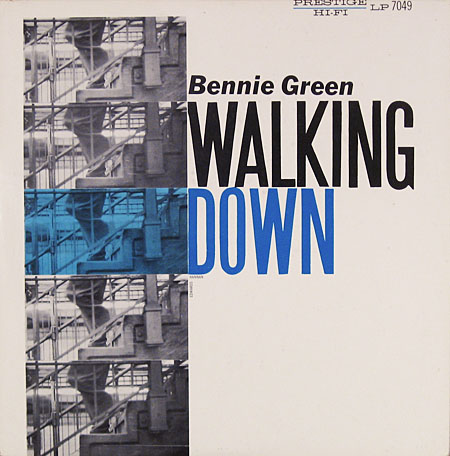

| Cover design by Tom Hannan, an abstract expressionist painter who doubled as a jazz album cover designer. |

There's one Green original on the album, the curiously named "East of the Little Big Horn," which seems never to have been picked up by anyone else. Too bad, good tune. And three standards. A favorite cut? It would be hard to choose. "Walkin' (Down) is a contender: it's always a treat to hear Bennie play the blues. But it's hard not to get caught up in the firestorm of traded licks between Green and Dixon on "It's You or No One."

The album takes away the parentheses, puts back the missing "g," and is called Walking Down.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb()/discogs-images/R-5246474-1388644697-6124.png.jpg)