Hope's youth included a brush with the law that rings a sadly familiar bell in the context of today's headlines: young black man shot in the back by the cops.

He was 17. He was treated for a bullet that narrowly missed his spine, and when he was released from the hospital six weeks later, he became the scapegoat of the incident, as he was arrested for assault, attempted robbery and violation of the Sullivan Law . He was charged with having participated in a mugging of three whites. Hope claimed in court that he had not been involved in any way with the mugging, but had been nearby, and, like others at the scene, had started running when the police started shooting. All charges were dismissed.

He served in the army in World War II, then returned to New York, where he was part of an emerging generation of bebop musicians. One was Johnny Griffin. who reminisced to Peter Watrous of the New York Times (quoted in Wikipedia):

We'd go to Monk's house in Harlem or to Elmo's house in the Bronx, we just did a lot of playing. I played piano a bit, too, so I could hear what they were all doing harmonically. But if something stumped me, I'd ask and Elmo would spell out harmonies. We'd play Dizzy's tunes or Charlie Parker's.

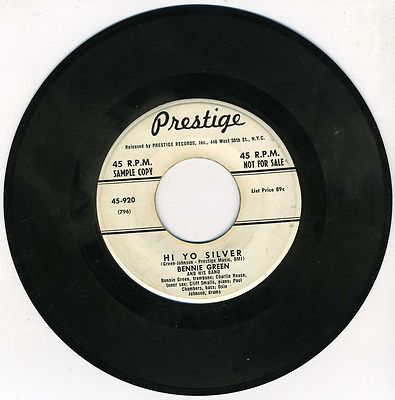

This was the second of three sessions for Prestige, and it's a strong showcase for Hope as pianist, leader and composer. His originals here are "Wail, Frank, Wail" and "Yaho." "Zarou" gets co-composer credit for Hope and Foster.

Freeman Lee plays on the first three tunes; the last two are a quartet.

Lee (also known as Charles Freeman Lee) had some good gigs during the bebop/hard bop era, playing with Snooky Young (on piano), with Sonny Stitt, Joe Holiday, James Moody and others on trumpet, and as a member of a vocal group backing up Babs Gonzalez. After his music career ended, he returned to the Midwest and joined his two schoolteacher sisters, teaching junior high school science. I hope is career as a teacher was as rewarding as his music career. It certainly was for his students. Here's a tribute from a student, at the Find a Grave website:

Mr. Lee was my Science teacher. He was a great educator. This was in the 70's in Michigan City Indiana, where his sister, Mrs Mary White, also lived and taught. He was a great and famous trumpeter and played with Duke Ellington. He used to tell us stories about his jazz days. He passed away in Ohio where his other sister, the famous educator Jane Lee Ball lived.- donna shindler

I got interested in the sister, and I discovered that she was an educator of some note: she had a thirty year career as a professor and chair of the humanities division at Wilberforce University in Ohio And from her 2011 obituary:

Elmo Hope's life was short and painful. I don't begin to know the reasons why people become addicted to heroin, but I'm sure that masking pain must be one of the main ones. So I can't help but be struck by how much joy there is in this music. With Foster (and Lee) the joy is boisterous and celebratory. In Hope's playing, it's very close to pure and unalloyed. especially on "Zarou," but really throughout.

This was a family that gave much to the world.As much as she loved education, Mrs. Ball enjoyed fiction and non-fiction writing as well. Despite the demands of career and family, she found time to turn her lively imagination and teaching gifts into words on paper. She wrote more than 100 articles for Salem Press, which publishes award-winning reference works, and also published five books: Toole, Arrigo, A Flea in the Ear, After the Split and Glorious to View — the latter two being carefully researched histories of her beloved Wilberforce University. At the time of her death, she had put the finishing touches on her memoir, Ebony Sweet, or Growing Up Colored Before Black Got Beautiful.

Elmo Hope's life was short and painful. I don't begin to know the reasons why people become addicted to heroin, but I'm sure that masking pain must be one of the main ones. So I can't help but be struck by how much joy there is in this music. With Foster (and Lee) the joy is boisterous and celebratory. In Hope's playing, it's very close to pure and unalloyed. especially on "Zarou," but really throughout.