I keep finding myself drawn back to the nonet and the 1948-49 Birth of the Cool sessions, because they were so important, and because no one seemed to know it at the time. Certainly no one one in New York. The engagement at the Royal Roost had been a flop, in good part, perhaps, because Count Basie was headliner, and Basie's audience might not have been the most receptive to the cool sound. And hardly anyone had listened to, or cared much about, the 78 RPM records that came out of the studio sessions for Capitol. Gerry Mulligan took the sound as far away from New York as he could, to California, where he developed it and adapted it for smaller groups, and created West Coast jazz -- or, as many said, gave birth to a new, cool jazz sound. Gil Evans seems to have gone fairly quiet-- we do know that he was always in touch with Miles.

Miles is thought to have completely turned his back on the experimental sound of the Nonet, bitter and disillusioned by the failure of the Jazz public and critics to appreciate what he had done for them, and that's mostly true, but not completely. He did make that one very experimental recording session with Lee Konitz. And, like Mulligan, he went as far away from New York as possible, but in the other direction, to Paris.

I knew Miles had been embittered by the nonet's reception, but I didn't realize how much. He stayed away from New York -- first Paris, then the Midwest, where the answer to how you gonna keep them down on the farm, after they've seen Paree? seemed to be, in part, a lot of heroin, but another was just that...staying out on the farm. Plenty of first class musicians came through Chicago, and we've already talked about the Detroit scene.

Miles had vanished after he did those Capitol sides with the (Birth of the Cool) Nonet. Nobody knew where he was. Somebody had said that he may be at home in East St. Louis, so while I was in Chicago on business I tracked him down. His father was a dentist, so I knew that his number would be in the phone book. I had met Miles at a Dial session where he recorded with Bird, but he didn't remember me. Anyway, he said if I'd send him money to get to New York, he'd be happy to record. I said that I was interested in doing a series of recordings, and that I wanted to sign him to a contract. He said alright, just get him to New York and we'd talk about it then. So, our basic idea was just to make records with different people, to record with the best people around. That's what we did until the end, when he had the quintet with John Coltrane, Red Garland, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones. But everything up to that point developed from where we would sit down and talk about it. Miles would mention who was in town, who he would like to record with. I'd say who I'd like to hear him record with. We'd kick ideas around.

His first studio album for Prestige was the January session with Bennie Green, Sonny Rollins and John Lewis.

This time it was Sonny Rollins, who, like Miles, was just hitting his stride as a major jazz figure, and who, like Miles, would become a colossus of American music. Tommy Potter and Art Blakey were veterans of bebop and of Prestige recording session. Walter Bishop, Jr., had made a couple of records, and had played at Minton's for a variety of people, idolizing Charlie Parker, learning from Bud Powell.

His bio in Allmusic.com says that he was "a valuable utility pianist on many a modern jazz session during the bebop era," which means what, exactly? A valuable utility infielder in baseball is someone who's not quite good enough to make the starting lineup, but can fill in at any position if the regular guy can't play that day. Doesn't seem to fit Bishop too well.

Jackie McLean was making his first record. He was in some impressive company--and it's said that he was more than a little nervous, because Charlie Parker was hanging out in the studio that day. So was Charles Mingus.and though he's not credited, it's generally accepted that Mingus played bass on "Conception."McLean definitely made a good impression, and not just with his alto sax playing. It's believed by many that he wrote "Dig."

I asked him about “Dig.” He said that he had brought that tune to a recording session with Miles, in 1951. Sonny Rollins was there too, and had brought a tune called “Out of the Blue.” When the album came out, Miles was listed as the composer of both tunes. Jackie was willing to consider it an error by the recording engineer. He later talked to a lawyer about getting proper credit, but was told that the returns would not justify the cost of pursuing it, so he just let it go.

Spitzer mentions several other tunes credited to Miles that were probably written by other artists, and then he says,

Some people have pointed out that in those years, it was not unusual for leaders to take credit for the work of their sidemen.

Now, I'm not here to defend Miles, who (a) doesn't need my defense, and (b) is guilty anyway, but I did wonder about that last statement, because it makes a certain amount of sense, because what exactly is jazz composition? Contemporary jazzman Steve Coleman has this to say about Charlie Parker:

I view Parker as a major composer, albeit primarily a spontaneous composer. His written compositions, similar to many other very strong spontaneous composers, were mainly jumping-off points for his spontaneous discussions.

Bird was noted for "spontaneous composition" -- that is, his improvised solos were actually original compositions, created on the spot. And what is a jazz composition, exactly? It's a tune, or a riff, or a series of riffs, that's played for one or two choruses at the beginning of a performance, and then played again at the end. In the interim, the musicians -- that's Davis, Rollins, McLean himself, Bishop, even Blakey -- are improvising, leaving the melody behind and creating their own musical units, in a piece that lasts for 7 1/2 minutes. The improvised solos are based on the chord structure of the opening chorus (at least until Ornette Coleman came along), and while they do follow that chord structure, it is, in many jazz compositions, the chord structure of an existing song. In the case of "Dig," it's "Sweet Georgia Brown." This is based on research -- I can't listen to "Dig" and say, "Oh, yeah, that's 'Sweet Georgia Brown.'" So maybe it's not so far-fetched for the leader to take composition credit. Or maybe it is.

That being said, "Dig" is a hell of a tune -- draws you in right away. But in spite of that, McLean's lawyer was probably right about the returns not justifying the cost of pursuing it. I haven't been able to find any other recordings.

And yes, it's 7 1/2 minutes long. In fact, all the tunes from this session are more than five minutes -- "My Old Flame" and "Out of the Blue" came out on 78s, each split up into Part 1 and Part 2. "Only a Paper Moon" and "Dig" the same, but also on 45. "Bluing" was too long even for that, so Parts 1 and 2 were on one 78, and Part 3 on the flip side of "Conception," which at 4:02 must have been just short enough to squeeze onto a disc.They were also all released on 45 RPM EPs. and "Dig" / "It's Only a Paper Moon" also came out as Prestige 45-321, which must also have been an EP, although not labeled as such, and also must have been much later. The 300 series of 45s includes later-generation jazzers like Yusef Lateef, and even rockers like Manfred Mann, as well as a lot of blues artists like Eddie Kirkland.

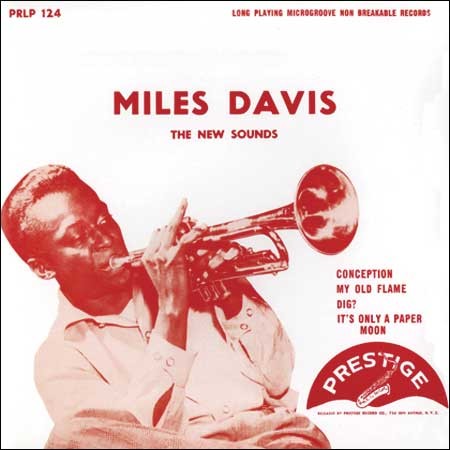

But this may have been the first Prestige session directly aimed at the LP format, and it was released in a few different formats -- as PRLP 124 -

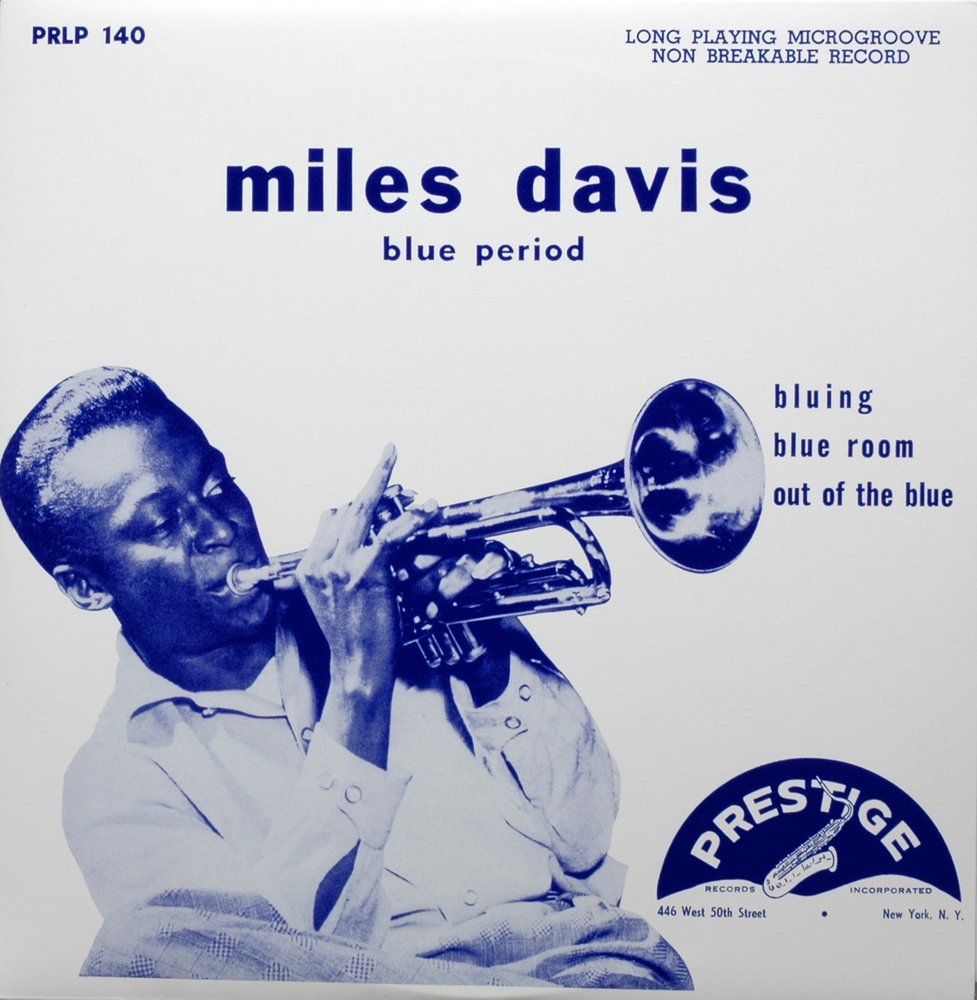

Miles Davis: The New Sounds (Conception/Dig/My Old Flame/It's Only a Paper Moon) and PRLP 140 -

The Blue Period ("Bluing" and "Out of the Blue," along with the alternate take of "Blue Room" from the previous session). Ira Gitler was writing the album cover notes by that time, and here's what he had to say (liner notes thanks to the

Plosin website, very complete on Miles).

THE NEW SOUNDS

When an artist is simultaneously recognized, by critics, fellow artists, and the public analogous to his art, as the foremost in his particular field, the work of the artist invariably substantiates the status given him by this audience. Such is the position of Miles Davis as the most important creative trumpeter today. Acknowledged first by musicians, Miles, soon drew the ears of discerning critics into appreciative attentiveness and finally the jazz public accorded him their appreciation in the Metronome and

Downbeat polls.

Of course, Miles is to be appreciated for bringing a new sound and conception to the trumpet but what really gives him his greatness are the intangibles he possesses, which enable him to transmit sweeping joy with his "wailing" solos and reflective beauty in the delicacy of his ballads.

This album gives Miles more freedom than he has ever had on record for time limits were not strictly enforced. There is opportunity to build ideas into a definite cumulative effect. These ideas sound much more like air-shots than studio recordings.

Upon the wonderful rhythmic foundation of Art Blakey's drums, Tommy Potter's bass, and Walter Bishop's piano, tenorman Sonny Rollins and altoman Jackie McLean are able to enjoy some of the unlimited time for their solo efforts. Rollins demonstrates the impact of the intangibles, again, with his solo on "Paper Moon". The way in which the solo is constructed and the feeling and time with which it is played, overshadow the marring reed trouble. McLean, still in his teens, is heard only on "Dig". He need not apologize for his youth after his work here. Walter Bishop appears in solo for a brief moment on "Conception" which gives only an inkling of his marvelous playing.

Here are New Sounds at greater length. Listen to them at great length.

and

MILES DAVIS - BLUE PERIOD

An album by Miles Davis represents modern jazz at its best. In this album as in Miles' PRESTIGE LP 124, the length of time for each selection is not restricted to the usual limits except in the case of BLUE ROOM, which was cut at a more conventional session. BLUING, the high spot of this set, is over nine minutes of freedom of expression on

modern blues chord changes. At the very end, Art Blakey continues playing after everyone else has stopped. If you listen closely, you will hear Miles say something like, "You know that ending man, let's do it again", but why do it again when you've captured the feeling in the solos of Walter Bishop, Miles, Sonny Rollins, Jack McLean, and the inventive drumming of Art Blakey. The advantage given by LP, of not having to make a "product" for the juke bokes, allowed us to keep this take. OUT OF THE BLUE (Miles' plea to get happy) was done at the same session and although not as lengthy as BLUING, still provided ample time for relaxed improvisation.

This album is a must to those who appreciate our modern jazzmen. I know that people who have missed hearing these musicians in person, will be especially gratified, because this is what they have been missing.

But the major release of this one came in 1956, remastered by recording genius Rudy Van Gelder, and issued as a 12-inch LP as

Dig. This, with the moody, dark cover image of Miles in shadow, and the terse title, was one of the benchmarks of hip in my young life.

And here's Gitler on the reissue:

These are some of the first "longer playing" recordings made possible by the advent of the LP. Recorded on October 5, 1951, this entire session has been remastered by top engineer Rudy Van Gelder. (The two remaining selections from this date, Conception and My Old Flame, are included in CONCEPTION, PRLP 7013)

Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins form one of the most empathetic and powerfully moving duos in jazz. Although they had recorded together before (Morpheus, Down, Whispering, Blue Room) this was their first chance to "stretch out" together on records.

These recordings have much warmth. The emotions jut out of all the solos. On Paper

Moon and Bluing this is especially true, but it is in evidence on the upper tempos too. Dig is fluid. The chord changes lend themselves to the long melodic lines that the soloists employ. There is also a continuity of feeling from one soloist to another which points up the aforementioned empathy.

The group is made a sextet by altoman Jackie McLean on all numbers but Paper Moon. Jackie, in his teens when these recordings were made, was then a disciple of Charlie Parker. The Bird influence is still with him but the light of it is partly directed through the prism of Sonny Rollins.

Incidentally, Bird was present for part of this record sort of visiting with his children: Miles who gained his greatest experience and had his largest pleasures playing with him; Jackie, the young disciple; and Sonny, the reed voice who has become the foremost standard bearer and advancer of the Parker tradition.

The swinging rhythm here features the explosive drive of Art Blakey, the subtle power of Tommy Potter and the sensitive accompaniment and solos of the unduly underrated Walter Bishop.

More credit to Jackie McLean for those chord changes (even if they are the chord changes to "Sweet Georgia Brown") that lend themselves to long melodic lines. And more credit given to McLean by Gitler, who had said on the previous liner note that he only appeared on "Dig."

And by the way, a busy day for Art Blakey. He played on the Bennie Green session as well.

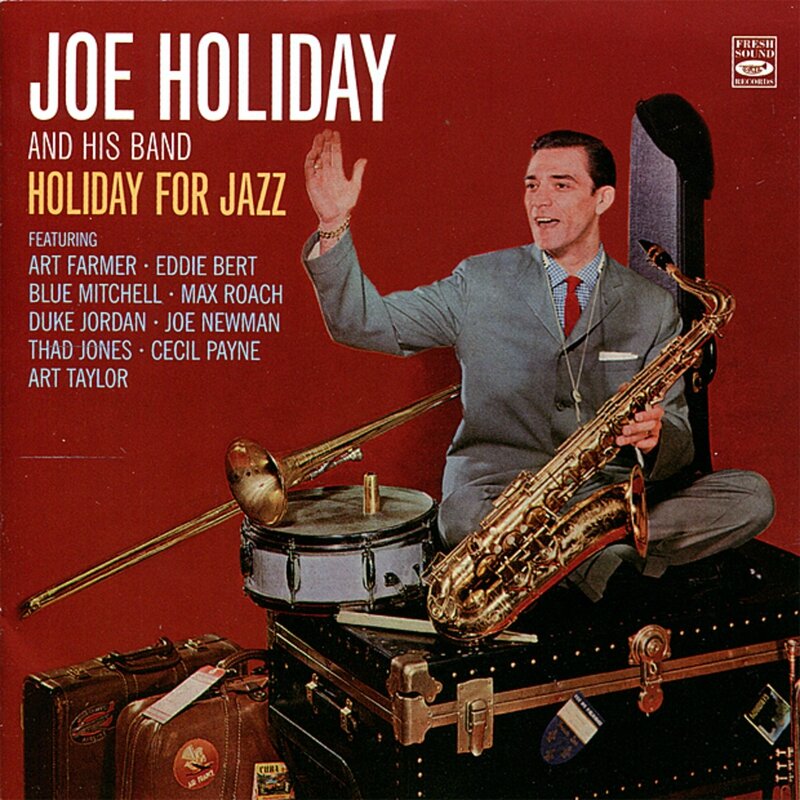

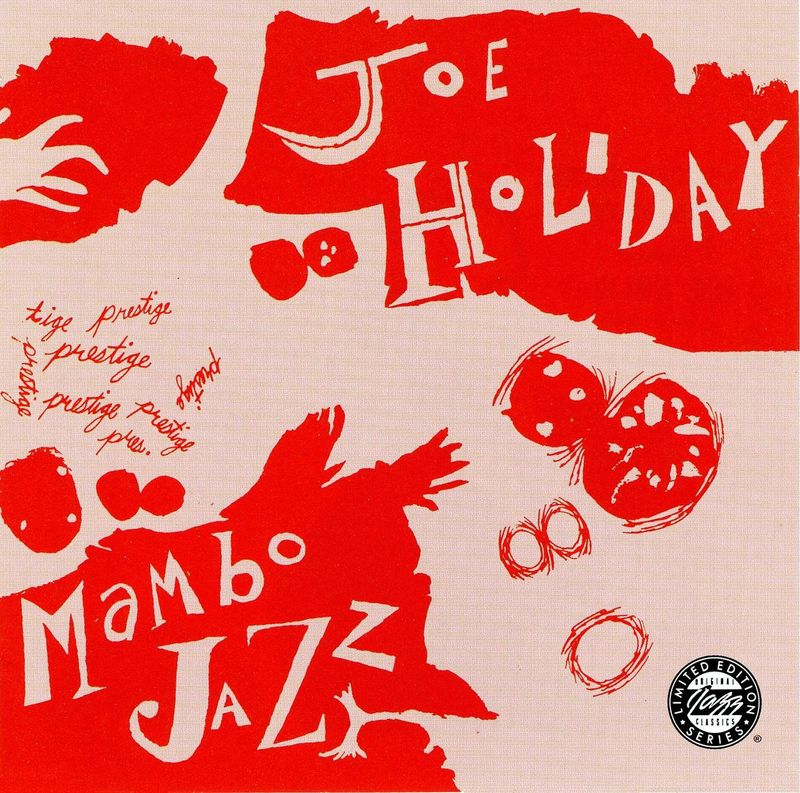

A word of advice on finding him -- I did a Spotify search on "Joe Holiday" and found nothing except a country singer named Joey Holiday. Looked on YouTube, found a few things, but none from this session (ultimately I did, so it's linked to here). Continuing to research Holiday, I discovered that he'd had a hit in 1951 with "This is Happiness," so I went back to Spotify, searched on "This is Happiness," and found the whole session and more. A lot of Holiday's work was reissued on Original Jazz Classics, one of the Prestige reissue labels, and Spotify has that, with album cover art that looks

A word of advice on finding him -- I did a Spotify search on "Joe Holiday" and found nothing except a country singer named Joey Holiday. Looked on YouTube, found a few things, but none from this session (ultimately I did, so it's linked to here). Continuing to research Holiday, I discovered that he'd had a hit in 1951 with "This is Happiness," so I went back to Spotify, searched on "This is Happiness," and found the whole session and more. A lot of Holiday's work was reissued on Original Jazz Classics, one of the Prestige reissue labels, and Spotify has that, with album cover art that looks

Te

Te