Tad Richards' odyssey through the catalog of Prestige Records:an unofficial and idiosyncratic history of jazz in the 50s and 60s. With occasional digressions.

Mountain in the room where

Nobody’s looking

Only mother bat soaring crazily

Across the moon can

Detect the cardboard cliffs

Grandfather trees

Wilted dizzy flaming leaves covering

Car wreck on the red rocks, charred from

Desert fire last December

After night when air disappeared

Everyone was caught walking with heads

Down hoods up

Hands pocketed eyes

Sideways mouths

Pinned open when Mountain was revealed

-- Jessica Ritacco

On the bed:

his sweatshirt and my black bag.

There’s an email on the computer screen,

a letter in my hand.

How did this happen?

Don’t ask. Just pack.

For the city:

I’d want my going-out

clothes: tiny top and tight pants.

Underwear of the sexiest order,

kick-ass boots,

black eyeliner.

Going farther south?

Pack less and more,

good books to read.

Don’t worry about what you’ll wear to bed.

Forget the eyeliner, take lipstick instead

and your favorite flavor of tea.

To stay here

all you have to do is

shove that black bag

back under the bed.

Put his sweatshirt back on.

Step into the night.

A bat soars crazily

across the moon,

her mouth full of insects.

You watch her flight

and the blue clouds

bluer because you’re by the Mobil sign.

It's a warm night.

You don't really need the sweatshirt.

-- Jennifer Whitton

Tapping an ordinary pen

It looks blue, against her chin

This child of a bat soars

Crazily across the moon

Moving nimble fingers

Through hair tinged in a wheat colored hue

Her mouth full of insects

Spewing forth the flies as a foam

Cracking knuckles, coupled with scratching on a pad

Those studious contemporaries

Resting their heads on hands

While with legs crossed her foot played out a beat

A solitary crimson star

Stitched by hand, on a pant seam

This swirling motion can draw you in

As the muted boy attempts to speak

There must be so much more

Yet all I know are these

Aesthetic things, Lives of aesthetic dreams

She’s turning to leave, walking slowly.

-- Keith Donnelly

This was several years ago. I was visiting photographer Dan McCormack, and he invited me to go out and do some landscape shooting with him. I told him that I didn’t do photography at all any more…I had decided that I was either going to make a total commitment to it or nothing, and I’d chosen nothing. I didn’t even own a camera any more.

He said “Come on, it’ll be fun, I’ll loan you a camera,” and finally I said OK. So we went out, shooting B&W, walking through the woods. At one point I tripped over a root and the shutter was tripped. At the end of the day Dan ran the film and printed some contacts for me. It was as I had thought…I had some pretty but conventional images. You don’t develop an eye in one day. And there was one negative which was just a blur of squiggly lines.

So we fast forward a few months. Dan has an opening in a good gallery, and I go to it, and there on the wall, matted and framed, is my blur. And it looks great.

This is a student poem from a few years ago – the first draft of a poem that went on to become much, much better – bright and sensual and well-realized.

First Kiss

The surf rushes forward,

falling with fury into a fluid fusion.

Waves whirl and intertwine.

Surges of synergic seduction plunge deeper

as they rise and tumble.

Ripples diminish, and bliss licks the shore.

The ocean’s caress recedes

and I, standing barefoot in the sand

know.

And my response, or the relevant part for this blog entry:

You’ve already let us know that the poem is going to be about a romantic, breathtaking moment, by titling it “First Kiss.” So you don’t need to explain that.

You also don’t need to explain to the reader that surf is a crashing, exciting phenomenon. So ANYTHING you say about the waves will carry that. Which means that’s the one thing you DON’T want to say, because you’re saying it already. Adding anything about rushing, or fury, is going to be redundant, and will feel like overkill.

Richard Hugo, in The Triggering Town, talks about "writing off the subject." I'd add another, similar suggestion: "Writing away from the subject."

Not only do you not need to say what you've already said, you don't need to say what you've already suggested. It’s close to impossible to write total non sequiturs. If something pops into your head, no matter how disconnected it may seem from what went before, it's connected because your head is the one it popped into.

So the connections are there. They can’t help but be. And that means you need to trust us as readers to make those connections. We will make them...sometimes even better than you, the poet, will, because we expect them to be there. If we know a poem is called "First Kiss," we'll connect anything that follows to the experience of a first kiss (whatever our experience of a first kiss is). So write away from it. Don't describe a first kiss. Describe something else.

Here's a stanza from a poem called “Summer Haiku” by Alicia Ostriker. You can find the whole poem at http://www.poems.com/summeost.htm. The stanza reads

A mother bat soars

Crazily across the moon,

Mouth full of insects.

Now, instead of “Summer Haiku,” let’s call the poem

FIRST KISS

That night, a bat soared

Crazily across the moon,

Mouth full of insects.

Once we see the title "First Kiss," we're going to relate whatever comes after to the idea of a first kiss. We may read this and think -- this is a kiss she shouldn't have gotten into. This is a dangerous first kiss -- irresistible because of its crazy danger, because of the moonlight...but dangerous.

Let’s put the same stanza under another title from another student poem: AFTER AN ARGUMENT WITH MY GIRLFRIEND, I QUESTION MY LOVE FOR HER

A bat soars

Crazily across the moon,

her mouth full of insects.

Uh oh. We're in the present tense now -- not looking back at the first kiss from a distance of time, but right there with the guy as his girl friend storms away, and his mind is full of doubts. Why is he looking at the sky, and not at her? Maybe because of the doubts. He wants to shut her out, at least for the moment. But he can't shut her out -- anything he sees is going to be relevant. And he sees a bat flying crazily across the moon -- the symbol of romantic love being crossed by the symbol of vampirism -- the creature who will first appear sexual and enticing, but will then suck the blood and the soul out of you. And in the speaker's mind -- because there's no way he could actually know this -- the bat is a woman.

Now let's stick it under a couple of other titles, drawn from poems.com (and without reading the poems, just grabbing the titles).

A DOG'S GRAVE

A mother bat soars

Crazily across the moon,

mouth full of insects.

He's visiting the dog's grave at night. He must be very lonely. And the solitary bat makes him feel even lonelier. But...it's a mother bat. Her mouth is full of insects for her babies. Even this world, bereft of a beloved dog, is full of life and nurturing in the strangest places...maybe? We have to read on. FAMILY REUNION

A mother bat soars

Crazily across the moon,

mouth full of insects.

You make the interpretation.

Or how about this? Ezra Pound's famous two-line poem.

IN A STATION OF THE METRO

The apparition of these faces in the crowd,

Bats flying crazily across the moon.

So that's the bat test. What happens to your poem if you stick the bat stanza into it? Does it derail the poem, or is it still strangely on track? If it derails the poem, maybe you're too locked into literal meaning. If it doesn't, then think about where else you can go.

The Education of Narcissus

From the jacuzzi, wreathed in scented foam,

He steps with his blow-dryer and his comb

To face that altar where all things are clearer,

To wit, his dressing table and his mirror.

He takes his inspiration and direction

By summoning the muse, his own reflection,

The which, in gratitude, he sweetly kisses,

This self-made-god, our latter-day Narcissus.

The poetry he writes, and thus inspires

Among his postulants, no more requires

A love of words or duty to the past

Beyond the headlines of the Tuesday last,

No binding strictures such as rhyme or meter

Or any length in excess of his peter,

The one tool of his trade he thinks so rare

He keeps it to himself, and will not share.

The first two ladies cross over, and by the opposite standThis same verse and chorus were repeated four times, but it's not as repetitious as it sounds. In every square dance which calls for partnering up with your corner lady, and the opposite ladies crossing over, a repetition of four means that by the end of the dance, you will have danced with every lady in your set, and be back with your partner.

The second two ladies cross over, and you all join hands

You bow to your corner lady, and honor your partners all

You swing your corner lady, and you promenade the hall

If I had a girl, and she wouldn't dance, I tell you what I'd do

I'd buy her a boat, and set her afloat, and paddle my own canoe

HIGH WOODS

HIGH AND HEALTHY

I praise the brightness of hammers pointing east

like the steel woodpeckers of the future,

and dozens of hinges opening brass wings,

and six new rakes shyly fanning their toes,

and bins of hooks glittering into bees,

and a rack of wrenches like the bones of horses,

and mailboxes sowing rows of silver chapels,

and a company of plungers waiting for God

to claim their thin legs in their big shoes

and put them on and walk away laughing.

In a world not perfect but not bad either

let there be glue, glaze, gum, and grabs,

caulk also, and hooks, shackles, cables, and slips,

and signs so spare a child may read them,

Men, Women, In, Out, No Parking, Beware the Dog.

In the right hands, they can work wonders.

provide a safe and loving haven for abused and abandoned horses and farm animals—animals who have never known warm shelter, spacious pastures, good food, or the touch of a kind hand. Since 2001, CAS has provided refuge for close to 400 such animals, including horses, ponies, cows, goats, sheep, donkeys, pigs, rabbits, and a variety of birds.We were there on Friday, which turned out to be a mistake...they're actually open only on Saturday and Sunday. I know from out experience at Opus 40 that it can be maddening to have people show up on the wrong day, just to look around, but the people at the farm could not have been nicer...all of them. They welcomed us, let us look around, even let Arick feed tomatoes to the pigs, including their newest one, Ozzie, a 4 month old Vietnamese potbellied pig.

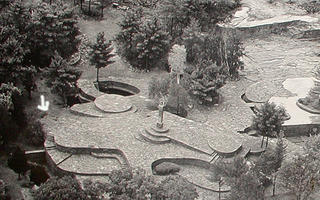

If you walk around to the south side of Opus 40 (marked with the arrow in the picture) you'll see an area where the stonework is more rough-hewn, without the lapidary precision that marks most of Opus 40. So you'd assume that represents early work, while he was still learning his craft, and you would of course be correct.

If you walk around to the south side of Opus 40 (marked with the arrow in the picture) you'll see an area where the stonework is more rough-hewn, without the lapidary precision that marks most of Opus 40. So you'd assume that represents early work, while he was still learning his craft, and you would of course be correct.Dear Tad,

Shame on you for not telling me years ago about Rachel Loden. I "discovered" her today at Poetry Daily, and I followed that up by checking out the Wild Honey Press website, then an interview of Rachel from Jacket magazine in Feb., 2003, in which she mentions working with you. Wow. All this time and you hipped me to her stuff. Shame on you. I like her stuff

a lot, as you might expect, and wish I'd known about her earlier. So it goes. In any case, it's nice to see that stuff like hers CAN get published and it's for damn sure livelier and more fun to read than most of the stuff that gets posted on P D or Verse Daily, or in most littery mags for that matter.

As an American who has lived in Europe for the last 24 years, I see on a daily basis how different the American and European economic systems are, and how deeply this affects the ways they produce, market and perceive art. America advocates supply-side economics, small government and free trade – all reflecting a belief that societies should minimize government expenditure and maximize deregulated, privatized global capitalism. Corporate freedom is considered a direct and analogous extension of personal freedom. Europeans, by contrast, hold to mixed economies with large social and cultural programs. Governmental spending often equals about half the GNP. Europeans argue that an unmitigated capitalism creates an isomorphic, corporate-dominated society with reduced individual and social options. Americans insist that privatization and the marketplace provide greater efficiency than governments. These two economic systems have created something of a cultural divide between Europeans and Americans.

The divisions between American and European arts-funding models are best understood if one briefly considers the changes that have evolved in U.S. economic policy over the last 30 years. Except for the military, there has been continual political pressure to reduce government. Even though the government’s budgets have continued to increase, arts funding has been particularly vulnerable to cuts. By 1997, the NEA’s funding was close to half its former high, and has only slowly regained some of its lost ground.

...

In its purest form, America’s neo-liberalism would suggest that cultural expression that doesn't fit in the marketplace doesn't belong at all. For the arts, the alternative has been to maintain a relatively marginalized existence supported by gifts from corporations, foundations and the wealthy. A system similar to a marginal and elitist cultural plutocracy evolves. This philosophy is almost diametrically opposed to the tradition of large public cultural funding found in most of Europe’s social democracies.

...

In culturally isomorphic societies, thought is less and less likely to move outside a pre-configured set of paradigms. In the 20th century, for example, we saw a culturally isomorphic essentialization of art in the "Gleichschaltung” of the Third Reich, in the Social Realism of the East Block, in the “Cultural Revolution” of Maoist China, and to an increasing extent in the mass media commercialization of culture in America. [7] Like the political divisions of the 20th century, these aesthetic orthodoxies reduced human expression to systemic concepts that tend toward the formulaic and reductionist. Since narrowed perspectives make it difficult to confront aspects of reality, a culture of self-referential rationalization evolves.

...

In the spirit of their mixed economies, Europeans would argue that many forms of artistic expression cannot be positioned or relativised within the mass market or its fringes. For them, culture must be communal and autonomous. They often see American culture as hegemonistic -- a totalizing and destructive assault on the humanistic, cultural and social structures they have worked so long and hard to create.

A general sense of the different perspectives concerning communal identity can be illustrated with an example now widely discussed in the States. Many Americans have seen how corporate-owned strip malls and Wal-Marts have deeply affected their cities and towns. The old downtown areas are abandoned as customers move to corporate businesses on the edge of town. Communal identity and autonomy, which are an important part of cultural expression, are replaced with a relatively isomorphic corporatism.

Europeans struggle to maintain a different model. Most cities and towns have thousand year histories that are reflected in the architectural and other cultural treasures of their various municipal centers. They employ zoning laws and other regulations, as well as public education, to protect their cities from the Wal-Martization that would be caused by embracing American-styled neo-liberalism. Europeans have large department stores and the occasional K-Mart, but their influence is kept within balance. They would consider the losses to their cultural identity caused by corporate uniformity to be too great.

.... Far from making music even more commercial, the European response has been to create a balance with public arts funding. In Germany, for example, cities with more than about 100,000 people often have a full-time orchestra, opera house, and theater company that are state- and municipally owned. A good deal of funding for these groups is set aside for new music. Europeans also administer this arts funding locally, and not from a remote Federal organization such as the NEA.

... In Germany, classical recordings compete strongly against pop. This is not merely a matter of history or coincidence. Europeans use their local public cultural institutions to educate their children and this creates a wide appreciation for classical music. The popularity is also based on a sense of communal pride. They support their local cultural institutions almost like they were sports teams. European society illustrates that music education leads to forms of creativity and autonomy that are often antithetic to mass media. The European view is not based on elitism or a dismissal of popular culture, but on an understanding that an unmitigated capitalism is not a seamless, all-encompassing paradigm - particularly when it comes to cultural expression.

...Germany, for example, has one full-time, year-round orchestra for every 590,000 people, while the United States has one for every 14 million (or 23 times less per capita.) Germany has about 80 year-round opera houses, while the U.S., with more than three times the population, does not have any. Even the Met only has a seven-month season. These numbers mean that larger German cities often have several orchestras. Munich has seven full-time, year-round professional orchestras, two full-time, year-round opera houses (one with a large resident ballet troupe,) as well as two full-time, large, spoken-word theaters for a population of only 1.2 million. Berlin has three full-time, year-round opera houses, though they may eventually have to close one due to the costs of rebuilding the city after reunification.

If America averaged the same ratios per capita as Germany, it would have 485 full-time, year-round orchestras instead of about 20. If New York City had the same number of orchestras per capita as Munich it would have about 45. If New York City had the same number of full-time operas as Berlin per capita it would have six. Areas such as Queens, Staten Island, and the Bronx would be nationally and internationally important cultural centers. The reality is somewhat different.

If America’s Northeastern seaboard had the same sort of orchestral landscape as Germany, there would be full-time, year-round professional orchestras (often in conjunction with opera houses) in Long Island, Newark, Jersey City, Trenton, Camden, Philadelphia, Wilmington, Baltimore, New Haven, Hartford, Springfield, Providence, and Boston. California would have about 60 full-time, year-round professional orchestras. Like Germany, the U.S. would suffer from a shortage of good classical musicians. There would be little unemployment for these artists. With that much creativity, it is unlikely Americans would stick to European repertoire and models. Even with half the German ratios, a starkly American musical culture would evolve that would likely change history.

It is also essential and informative to place these numbers in the context of the dismal social conditions in almost all major American cities, since these are areas where classical music would normally thrive. A recent article in The New York Times, for example, notes that Philadelphia has 14,000 abandoned buildings in a dangerous state of collapse, 31,000 trash-strewn vacant lots, 60,000 abandoned autos, and has lost 75,000 citizens in recent years. [10] Regions such as the south Bronx, Watts, East St. Louis and Detroit, just to name a few, show that Philadelphia is hardly an exception. The populations living in our dehumanizing ghettos are measured in the tens of millions. It seems very likely that the problems with arts funding in America are closely related to the same social forces that have caused the country to neglect its urban environments. This naturally leaves many Europeans wondering why America is so intent on exporting its economic and cultural models.

The problems of arts funding are seldom the topic of genuinely serious and sustained political discussion. The cultural and political system has become so isomorphic that most Americans do not even consider that alternatives could be created to institutions such as network television and Hollywood. With only one percent of the military’s $396 billion budget, we could have 132 opera houses lavishly funded at $30 million apiece. (That much funding would put them on par with the best opera houses in the world, and as noted, likely lead to forms of expression more distinctly American.)

The same sum could support 264 spoken-word theaters at $15 million each. It could subsidize 198 full-time, year round world-class symphony orchestras at $20 million each. Or it could give 79,200 composers, painters and sculptors a yearly salary of $50,000 each. Remember, that’s only one percent of the military budget. Imagine what five percent would do. These examples awaken us to the Orwellian realities of our country and how different it could be. Given our wealth, talent, and educational resources, we are losing our chance to be the Athens of the modern world.

...

Another example of the loss of intelligent discourse is the discussion surrounding the current proposed $18 million increase for the NEA. This sum represents only seven-thousandths of one percent of the proposed 2005 U.S. budget, a number almost too infinitesimal to comprehend. And yet the topic is once again being opportunistically exploited as a political battering ram.

In Europe, by contrast, funding for the arts is a central platform of every major political party. Lively and varied artistic expression is considered one of the most important forums for national discourse. Politicians literally search for opportunities to speak about the arts because it is politically advantageous. The dialog is generally intelligent, meaningful, and carefully considered.

This is the first piece of advice I give my writing students. And the last. And several times in between.

We all start writing for the same reason. Our first impulses are always: we want to write because we have something to say. We have thoughts we want to express to the world, and we have feelings we want to share with the world.

So we start writing, and before long (if we’re lucky), but eventually (guaranteed), we will realize something. And this is the mantra I want you to remember all through this course, and all of your writing career:

All your thoughts are shallow, and all your feelings are banal.

And once that realization hits us, we can react in three ways, all of them OK.

We can say "OK, it's true. All my thoughts are shallow, and all my feelings are banal. So what? They're still my thoughts and feelings, and I just write to please myself." And there's nothing wrong with that. We just have to realize, then, that our writing is private rather than public. It's for our journals, and letters to our closest friends, and it's to be put away in attic so that someday our great-great-grandchildren can find them and say, "Wow, g-g-grandpa was really cool back in the 21st century."

Or we can say, "My God, it's true. All my thoughts are shallow, and all my feelings are banal. What am I doing? I'd better give up writing." And that's OK, too -- not everyone has to write. Just don't stop reading.

Or we can say, and we do say, if we're lucky or unlucky enough to be this kind of person, "My God, it's true. All my thoughts are shallow, and all my feelings are banal. That means I'm FREEEEEE!!!!!!!" And you are. You are no longer obligated to make sure the world gets your thoughts and feelings. You can explore words, and images, and all the possibilities of language.

First day of my workshop with the teenagers. It’s probably a good thing that kids don’t know that when you walk into a classroom, you’re a hell of a lot more nervous than they are. That’s because you know, much more than they do, how much it matter. You’ve got this awesome responsibility not to waste their time, and to give them something to take away that’ll make a difference in who they are and what they understand.

In teaching a poetry workshop, I focus on giving my students tools for making poetry. I try to stay away from self-expression. That happens whether you encourage it or not. The question is how you’re going to construct the vehicle for your self-expression.

“Poet” comes from a Greek word which means “maker.” A poet makes something out of words. He/she is a carpenter, making a house out of words and sounds and rhythms and images, which someone else—many other people—will be able to move into and furnish and live in. A good poem doesn’t tell the reader how you feel; it gives the reader a structure in which to experience in a new way how he/she feels.

I started off by using a structure that I’ve used before.

I play the class a recording of Buddy Holly singing "Peggy Sue Got Married." It's from the "Apartment Tapes" - the acoustic demo tapes that Holly made in his apartment just before he died, of songs he planned to record later. I play the song, and then ask the kids for the data - and data only - of what they've just heard. They always start by saying Well, Peggy Sue got married. I say yes, but how do you know that? Well, he said it. Yes...so part of the data is words. And this is, in fact, what I'm looking for.There are words. Rhythm. Melody. A guitar. A male voice.

I play it for them again, and pass out a lyric sheet:

Please don't tell

No no no

Don't say that I told you so

I just heard a rumor from a friend

I don't say

That it's true

I'll just leave that up to you

If you don't believe me I'll understand

You’ll recall the girl that's been in nearly every song

This is what I heard

Of course, the story could be wrong

She's the one

I've been told

Now she's wearing a band of gold

Peggy Sue got married not long ago

What are the feelings in the song? You can't really talk about art without talking about feelings. If I told you I'd been to a concert, and you asked what I'd heard, and I said words, melody, rhythm, a guitar and a male voice, you'd think I was nuts. So we start making a list, and it comes out to be things like sadness, doubt, regret, nostalgia, uncertainty, envy, etc. Then I ask, who is the song about, and generally the answer is "Peggy Sue." Which is pretty much the right answer. Then I ask, how do you know all this stuff? How do you know that the singer feels sadness, doubt, regret, nostalgia, uncertainty, envy? Well, he says it. You get it from the words.

Then...and I can't really convey this in writing, you have to hear it -- I play the overdubbed version that was released commercially, and ask the same question again. What's the data? How has it changed?

It's changed by the addition of drums and an electric guitar. It's also changed - I generally have to point this out - by what amounts to the removal of the acoustic guitar. It's buried so far down in the mix you can't really hear it any more.

And the feelings? Are they different? Yes, they are. It's not the same song any more. It's more upbeat, lighthearted. It's a dance song. The sadness and nostalgia are gone - as a student once said, "It's like she's gone, but he's got a bunch of friends over, and they're partying and having a good time, and he doesn't care. He doesn't miss her." Also, with the hard edge of the electric guitar and drums (by Jimmy Glimer and the Fireballs) there's an edge of anger, of defiance -- a rock 'n roll edge. Who's the song about now? It's really not about Peggy Sue any more. It's about the singer. She's gone and forgotten.

So how can this happen? Same words. Didn't the feeling come from the words? Not that simple. Art is more complex than that. And - as one kid in this group said about the second version - he's just covering up his real feelings. He really misses her. And as another said about the first version - at first you think he really cares, then you think maybe he doesn't. And they were both right. Emotions are complex and often contradictory. Art makes us feel that complexity.

Next, I ask: There's a symbol in the poem. What is it?

That's easy - the band of gold. Right - and what's the band of gold a symbol of? That's easy - marriage. Right...but here's where it gets interesting. What's marriage a symbol of? Maybe not the same thing in each version. In the acoustic folkie version, it seems like a symbol of growth. She's gone on to a richer, more rewarding life...she's grown up. He's left all alone in a little room with his guitar. In the rock 'n roll version, it may be a symbol of limitation. She's grown up, taken on adult responsibilities, said goodbye to fun and partying and rock 'n rolling. But he doesn't have to do that...at least not yet. He still has his youth and his freedom.

OK, there's another symbol in the song. What would that be? A good class gets it...this one did.

The girl who's been in nearly every song.

Now, this is the line which takes this very good song and makes it exceptional. This is an incredible symbol. What/who is "the girl who's been in nearly every song"? In the acoustic-folk version, she's the girl you can never forget. Every girl you see on the street reminds you of her. Every song reminds you of her. In the rock 'n roll version, where she's gone and forgotten, maybe that line tells you "They're all the same. Girls are like buses - if you miss one, there'll be another along in ten minutes."

The girl who's been in nearly every song is a muse...the muse of rock 'n roll. If you're a sad guy sitting a room alone with an acoustic guitar, the muse maybe has moved on. If you're a rocker, with a band backing you up, then maybe it doesn't matter if Peggy Sue goes and gets married - rock and roll will never die, and girls will always go on inspiring songs.

And...the power of all that comes from the image. "Women are all the same...they're like buses, another one will be along in ten minutes" tells you what to think. "The girl who's been in nearly every song" opens up your mind to a range of possibilities.

Anyway...that's the idea. That’s where we started.