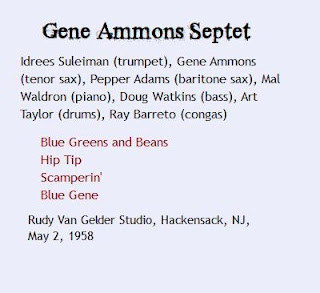

"Mal, you're playing a gig with Gene Ammons this Friday. Come up with some tunes that'll suit him."

"On it."

By 1958, jazz and rhythm and blues had gotten a divorce, and rock 'n roll was the co-respondent. Jazz had won custody of Gene Ammons, but that gritty rhythm and blues consciousness was still a part of him, a different consciousness from that which informed the newer hard-bop, jazz-funk style that was coming to be associated with Blue Note.

So Mal Waldron did contribute all four tunes to this session, and they couldn't be righter for Ammons: funky, rhythmic, great ensemble sections, loose enough to provide plenty of space for improvisation. A lot of jazz tunes are simple riffs brought in for the session, based on the changes or even the melodic hooks of other tunes, serviceable for some great blowing but not likely to enter the jazz library.

So Mal Waldron did contribute all four tunes to this session, and they couldn't be righter for Ammons: funky, rhythmic, great ensemble sections, loose enough to provide plenty of space for improvisation. A lot of jazz tunes are simple riffs brought in for the session, based on the changes or even the melodic hooks of other tunes, serviceable for some great blowing but not likely to enter the jazz library.

And so it is with these, but Waldron always gave you a little more, and any of these could have blossomed into a standard. "Hip Tip," smeary and bluesy and atmospheric as a smoky alleyway, could have been another "Harlem Nocturne," and maybe would have been, if it had had a more anthemic title. It has been covered, with a very different sensibility, by a Latin-jazz-funk star of the 1980s, Bobby Rodriguez. David "Fathead" Newman made "Blue Greens and Beans" the title cut of a 1990 album, and Newman of course came from the most prestigious of rhythm and blues pedigrees: the Ray Charles orchestra of the Atlantic years. Ammons pays tribute to the blues and bebop both on this cut, throwing in one of those little unexpected quotes from an odd source, in this case "Isle of Capri."

Idrees Suleiman, Ammons, and Pepper Adams know their way around the blues, know how to construct killer jazz solos, and know how to play together. Ammons would go to a sparer sound in later albums, but this period, with his sextets and septets, produced some richly satisfying music.

Bobby Rodriguez may have come to this album, and "Hip Tip," through admiration for Ray Barretto, but it's "Scamperin'" that really showcases the conguero. It could have been a hit too, with its Latin rhythm and the all-out wildness of the horn players. "Blue Greens and Beans" was the two-sided 45 from this session, and no complaints...it deserved it. But I might have gone with "Scamperin'."

"Blue Gene" was the title track for the album, and it has some lovely soulful playing on it, and it's the time that was also included on a compilation album later on, called Gene Ammons - Biggest Soul Hits.

So in other words, you couldn't go wrong with any one of these Mal Waldron compositions, or any one of these septet treatments of them. This album is pure pleasure.

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 2

Listening to Prestige Vol. 2, 1954-1956 is here! You can order your signed copy or copies through the link above.

Tad Richards will strike a nerve with all of us who were privileged to have lived thru the beginnings of bebop, and with those who have since fallen under the spell of this American phenomenon…a one-of-a-kind reference book, that will surely take its place in the history of this music.

--Dave Grusin

An important reference book of all the Prestige recordings during the time period. Furthermore, Each song chosen is a brilliant representation of the artist which leaves the listener free to explore further. The stories behind the making of each track are incredibly informative and give a glimpse deeper into the artists at work.

--Murali Coryell

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-10643447-1501534721-5552.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-3232202-1321552715.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-4857564-1377915740-1205.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-2812513-1302152370.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-2097503-1492440052-8295.bmp.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3070310-1344623623-8595.jpeg.jpg)