There were some significant differences. Burrell and Coltrane were the only front line instruments, where the other session had been a sextet. Paul Chambers was on bass instead of Doug Watkins, and on drums, an up and coming player making his Prestige debut.

He's a welcome addition to the Prestige scene, and he makes his presence strongly felt from the first tune of the session, a Burrell composition, "Lyresto." He sets a groove right from the beginning, and comes in later for a dynamic solo.

(A side note: we had the honor of presenting Jimmy Cobb in concert at Opus 40 just this summer and his playing remains sublime.)

Burrell and Coltrane are no strangers to each other, and they really know how to play together, either in a quintet setting or just the two of them, on "Why Was I Born?". a ballad standard by Ted Fio Rito, a prolific if not widely known conductor, "Why Was I Born" has been a favorite of jazz singers (including an unlikely jazz singer,

Bob Dylan), and more than a couple of instrumentalists. This is an unusual and haunting cut, and different enough from the rest of the album that I'll include it as a second listening suggestion.

Tommy Flanagan contributes two originals, each a tribute to a bandmate ("Freight Trane" and "Big Paul"), and his customary precise and original piano playing. "Freight Trane" has had a few covers, some of them unlikely (not as unlikely as Bob Dylan) like the U.S. Navy Commodores Jazz Ensemble.

Once again, one wonders if this album got the distribution and acclaim that it deserves. It was held back till 1963, and then released on New Jazz. It must have gotten some sort of a push, since "Freight Trane" was also released as a two-sided 45 at what one presumes is the same time (release dates of 45s are hard to pin down). The album was title Kenny Burrell and John Coltrane. A much later re-release on Prestige was called The Kenny Burrell Quintet with John Coltrane, which is also just a little curious. It came out in 1968, a year after Coltrane's death, and one would have thought his name would get top billing at that point. Goes to show that Burrell was also held in really high esteem, or else that Bob Weinstock was running out of steam (he would get out of the business four years later) and not making carefully crafted marketing decisions.

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 2

Listening to Prestige Vol. 2, 1954-1956 is here! You can order your signed copy or copies through the link above.

Tad Richards will strike a nerve with all of us who were privileged to have lived thru the beginnings of bebop, and with those who have since fallen under the spell of this American phenomenon…a one-of-a-kind reference book, that will surely take its place in the history of this music.

--Dave Grusin

An important reference book of all the Prestige recordings during the time period. Furthermore, Each song chosen is a brilliant representation of the artist which leaves The listener free to explore further. The stories behind the making of each track are incredibly informative and give a glimpse deeper into the artists at work.

--Murali Coryell

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

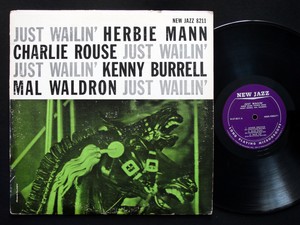

Listening to Prestige 267: Prestige All Stars

I won't run counter to Prestige's egalitarianism by anointing a first among equals (and I wouldn't want to), but Herbie Mann is of notable interest because (a) the flute is becoming a popular part of jazz small group instrumentation, and (b) he was around before it was.

And that wasn't so long ago. Jazz is unique in cultural histories for its compression, which is why during this one decade you can find virtually every past style of jazz, and many of the players who will create jazz's future. So Herbie Mann's first album, in which he more or less introduced the flute into modern jazz, came in 1955, for Bethlehem. His breakout album was probably Flute Flight, for Prestige in 1957, with Belgian flutist Bobby Jaspar, who was to die young.

Jerome Richardson came on the scene around the same as Mann. Yusef Lateef was making music, but did not leave Detroit for New York until 1957. Eric Dolphy joined the Chico Hamilton group in 1958.

So anyway, by just a couple of years, Mann was a pioneer, and while a couple of years doesn't necessarily make a difference, in this case it seems to. Yusef Lateef in many ways represents the new sound of the flute in jazz, and his influences are eclectic, very much including the Middle Eastern sound he learned from a fellow worker on the Chrysler assembly line in Detroit. Mann felt that influence too (listen to "Tel Aviv" on the Bobby Jaspar session), but he's much more mainstream, and especially much more bluesy. He's not afraid to use the lower register of the flute, and he certainly foreshadows the soul jazz sound of Memphis Undergroind that would make him a star in the 1970s.

Once again, this session proves what many Prestige sessions of this era have proved before: If you have Mal Waldron in your group, you're well advised to ask him to bring some tunes along--you can't go wrong. "Minor Groove," "Blue Echo" and "The Gospel Truth" are all Waldron.

Kenny Burrell, no slouch as a composer, contributes "Blue Dip." And he also contributes some first class playing.

"Jumpin' With Symphony Sid" is the Lester Young standard, and my favorite on the album because I'm a sucker for the classics. But for other reasons too. Burrell hooks the listener immediately with his first statement of the head, and then they go through it again with a guitar-flute duo that's if anything even catchier, then solos by all four of the principals, each of which captures the swinging qualities and the boppish qualities of the tune. Jazz aficionados listening to this track will definitely not think they're listening to Lacy.

And they wrap it all up in three and a half minutes, which should have made it a natural for release as a single, but didn't.

There is a side trip into what would come to be called World Music, with a composition by activist composer Cal Massey, "Trinidad."

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 2

Listening to Prestige Vol. 2, 1954-1956 is here! You can order your signed copy or copies through the link above.

Saturday, August 26, 2017

Order Listening to Prestige Vol 2

Listening to Prestige Vol. 2, 1954-1956 is here! You can order your signed copy or copies through the link above.

Tad Richards will strike a nerve with all of us who were privileged to have lived thru the beginnings of bebop, and with those who have since fallen under the spell of this American phenomenon…a one-of-a-kind reference book, that will surely take its place in the history of this music.

--Dave Grusin

If you want a personalized signed copy, email me at tad@tadrichards.com. I tried to make a box for that on the paypal form, but it didn't work.

Wednesday, August 16, 2017

Listening to Prestige 266: Red Garland/John Coltrane

Joyously easy, starting (in the order on the released album) with "This Can't Be Love," the Rodgers and Hart standard. There was always an ironic underpinning to Lorenz Hart's work. When he says "This can't be love, because I feel so well," he kinda means it. Love does really awful things to you, and since those things haven't happened--yet--

Joyously easy, starting (in the order on the released album) with "This Can't Be Love," the Rodgers and Hart standard. There was always an ironic underpinning to Lorenz Hart's work. When he says "This can't be love, because I feel so well," he kinda means it. Love does really awful things to you, and since those things haven't happened--yet--this probably isn't it. But this version is so joyous and upbeat that it could be a Rodgers and Hammerstein song. It also a lyrical, swinging, three minute bowed bass solo by Paul Chambers that'll lift your mood if it's not there already.

"Since I Fell For You" was written as a rhythm and blues number by bandleader Buddy Johnson for his sister Ella, and it's since become a beloved standard of R&B, pop and jazz, or, if you're Dinah Washington, all three. Garland and company give it a jazz treatment here, soulful and lovely.

"Crazy Rhythm" was written by Irving Caesar, Joseph Meyer and Roger Wolfe Kahn, who didn't generally write together, but if you take all the work they did with other collaborators, and lump it

together, you have one hell of a songwriter. Even separately, they're impressive. I've written about people who left music to become charter boat skippers, to run insurance agencies, to join family air conditioning businesses, but Roger Wolfe Kahn has them all beat. He left music to become a test pilot. The Garland trio can handle all rhythms, crazy or otherwise.

Garland always had the most eclectic tastes, and the ability to pull a great session together from disparate sources. "Teach Me Tonight" is a popular song from the 50s, that era on which the book of Great American Songs was supposed to have closed. But this is another that's received quite a bit of attention cross-genre (including, again, Dinah Washington, who crossed nearly every genre). In jazz, piano players have liked it -- Garland, Erroll Garner, Oscar Peterson.

"It's a Blue World" was written by Bob Wright and George Forrest, best known (basically only known) for the Broadway show Kismet. If Red Garland is an eclectic song-picker, "It's a Blue World" is an eclectic song, with versions by a wide range of jazz performers, including Glenn Miller, Billy Bauer, Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis and Coleman Hawkins. It's been a favorite of jazz singers, too, including, most recently, Amy Winehouse.

I love Red Garland's trio work, always, but Coltrane is Coltrane.

If Garland, Chambers and Taylor were having a busy day, Garland, Chambers and Coltrane were having a busy week. Don't forget that while they had stayed behind at Prestige, they had also migrated to Columbia with Miles Davis, and three days before turning up on Rudy Van Gelder's doorstep, they had been in a Columbia studio recording one of Miles's classic albums, Milestones, the one that welcomed Cannonball Adderley to the group.

Trane was now pushing forward with more urgency, and starting to separate himself from the pack even more than he had done previously. This session is credited as his first exploration of the technique that came to be called "sheets of sound." I am not musicologist enough to understand its nuances, let alone explain them. Here's fromthejazzpianosite:

As we covered in a previous lesson, to improvise vertically means to think in terms of chords and chord progressions – so your solo traces out each individual chord in the progression. While to improvise horizontally means to think in terms of scales, modes and keys – so your solo isn’t tracing out each individual chord, but rather you are just playing a particular scale over the entire progression. The end result can be very similar. A vertical solo can sound exactly the same as a horizontal solo – it’s just a different way of thinking about improvisation.And so the Sheets of Sound technique is a vertical improvisation technique; that is, it uses arpeggios, patterns, licks and scales that trace out each chord in a progression.

The writer goes on to explain that there are a plethora of scales and arpeggios "that you could plausibly use to improvise over this chord," and lists a number of them, but points out that

The same website quotes Coltrane:If you play all of these scales/arpeggios in their entirety over [your basic chord], you are playing Sheets of Sound. Now, obviously, this is impossible so you just try squeeze in as much as you can.Coltrane tried to squeeze every possible harmonic implication into his solo – play every possible chord and every possible scale for each chord.

He does play melodically on this session, especially on Tadd Dameron's beautiful "Good Bait." Dameron was what might be called a musician's musician -- revered by the jazz community, not well known outside of it, so his compositions were special, not only because of how good they were, but also because jazz owed him a special debt.About this time, I was trying for a sweeping sound. I started experimenting because I was striving for more individual development. I even tried long, rapid lines that Ira Gitler termed “sheets of sound” at that time. But actually, I was beginning to apply the three-on-one chord approach, and at that time the tendency was to play the entire scale of each chord. Therefore, they were usually played fast and sometimes sounded like glisses.I found there were a certain number of chord progressions to play in a given time, and sometimes what I played didn’t work out in eighth notes, 16th notes, or triplets. I had to put the notes in uneven groups like fives and sevens in order to get them all in.I could stack up chords, say on a C7, I sometimes superimposed an Eb7 up to an F#7, down to an F. That way I could play three chords on one. But on the other hand, if I wanted to, I could play melodically…

And he plays out there, especially on an Irving Berlin standard. As Bob Weinstock recalled it,

We were doing a session and we were hung for a tune and I said, "Trane, why don't you think up some old standard?" He said, "OK I got it.["]...and they played "Russian Lullaby" at a real fast tempo. At the end I asked, "Trane, what was the name of that tune?" And he said, "Rushin' Lullaby". I cracked up.The Trio session sat on the shelf for a long time, finally released in 1970 as It's a Blue World. "Crazy Rhythm" rushed the tempo on that, appearing on Garland's 1962 release, Dig It! as well as the later album.

The Coltrane session came out in 1958 as Soultrane, although it does not include the Tadd Dameron composition of the same name that was written for Coltrane. "Good Bait" and "I Want to Talk About You" were released on separate 45s, each divided into Parts 1 and 2.

Listening to Prestige Vol. 2, 1954-1956 is very close to release. Order your advance copy from tad@tadrichards.com

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3070310-1344623623-8595.jpeg.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment