Back to Prestige. We are now in early February of 1957, and this is already the eighth recording session for Prestige. Fridays with Rudy had become a regular thing, and a few Saturdays were being added too. It's a good thing the Van Gelders weren't Orthodox Jews, Muslims or Seventh Day Adventists.

This was a busy schedule. To compare:in the first quarter of 1957, Prestige had scheduled 21 sessions, Blue Note 12, Riverside 5, Fantasy 4, Pacific Jazz 4.

Atlantic had 9 modern jazz sessions, 5 of them for the same album (Chris Connor sings Gershwin).

Only Norman Granz outdid Bob Weinstock, with 13 jazz albums on Verve (many of them covering several sessions, including 5 different sessions on consecutive day for one Billie Holiday album with Ben Webster and Harry "Sweets" Edison, so altogether it added up to a couple of dozen studio sessions). So in terms of actually turning out product, Prestige was way ahead of even Verve, but that seems to be related to Bob Weinstock's no rehearsal, very few takes philosophy.

Which means, for us, from the vantage point of the 21st Century, an incredible record of one of the most fertile and creative periods in jazz history. 1957 was Weinstock's eighth year running a jazz label and producing jazz records, and his enthusiasm hadn't flagged. If anything, he seems to have been more committed than ever to chronicling the music of his time.

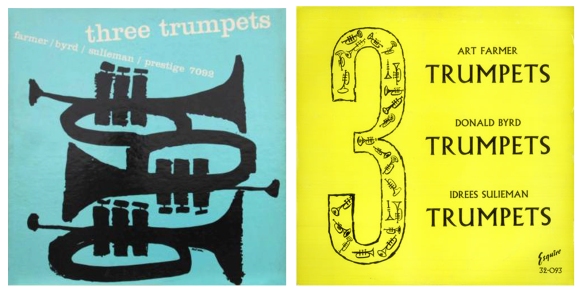

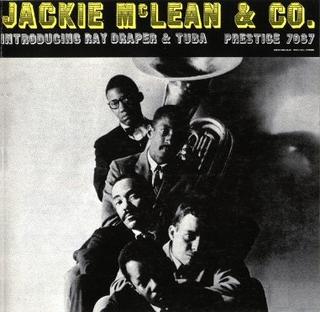

He had his regulars. Gene Ammons, Art Farmer, Donald Byrd -- Kenny Burrell and Jackie McLean were new additions to that list--and the rhythm sections he called on over and over. Legends passed through and went on to other labels. But there was also all that urge to try different things, different combinations, to mix things up. I've quoted before from an interview with Weinstock, talking about working with Miles Davis:

And that is one important part of the greatness of jazz as a genre. The history of any art form is oten the same: folk art, popular art, high art. In jazz it happened so quickly. You didn't have to look to the past for the tradition; it was right there next to you. In 1957 Louis Armstrong was still playing. Kid Ory was still playing. And Benny Goodman and Erskine Hawkins and Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young and Dizzy Gillespie. John Coltrane was just beginning to hit his stride. Ornette Coleman was in LA, playing music that no one could understand, but he would start putting that music on record the following year. Eric Dolphy was getting his first major gigs with Chico Hamilton. Disciples of Lester Young like Red Prysock and Sam "The Man" Taylor were revitalizing the music scene playing rhythm and blues, and turning on teenagers as part of Alan Freed's rock 'n roll stage shows. And they crossed genres: Louis Armstrong played with Dizzy Gillespie, Lionel Hampton with Stan Getz. Hampton was a one-man genre-bending army, a swing era standout whose music became a gateway to both bebop and rhythm and blues.So, our basic idea was just to make records with different people, to record with the best people around. That's what we did until the end, when he had the quintet with John Coltrane, Red Garland, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones. But everything up to that point developed from where we would sit down and talk about it. Miles would mention who was in town, who he would like to record with. I'd say who I'd like to hear him record with. We'd kick ideas around.

And on Fridays (and sometimes Saturdays) in Hackensack, New Jersey, Bob Weinstock was mixing and matching, coming up with different combinations, creating a catalog gives us such a range, such a blend, of the jazz of the 1950s.

An All Star group with three trumpets worked out well, so why not up the ante to four, and make it saxophones this time? That, of course, has been done enough to make it a fairly classic lineup, but usually with tenors. Would four alto saxes be called the Four Kid Brothers?

Phil Woods and Gene Quill would record together a number of times, partly because of a brotherhood of tonality, partly because "Phil and Quill" sounded catchy. Sahib Shihab was one of the important saxophone players of his era, playing important dates with Thelonious Monk, Benny Golson, and fellow Islam convert Art Blakey. Hal Stein did next to no recording under his own name, so he's not as well known, but he was a highly respected side man who played with a host of jazz greats, on tenor and alto.

As with the three trumpets on the earlier All Star session, or for that matter the Four Brothers, it's not necessarily going to be clear who's playing which solo, unless you're a very trained ear (and maybe not even then--the greats didn't always get their identifications right on Leonard Feather's blindfold tests), but you can tell that there are different voices, and that they're engaging in some brilliant colloquia on how to interpret a tune on the alto saxophone.

And let's talk a little about the tunes they're interpreting. Mal Waldron continues to make his mark as a composer, "Pedal Eyes" and "Staggers." A bonus in listening to a Waldron composition is that Waldron is given a little more solo space, which is always a joy, but a particular joy when he's improvising on one of his own tunes. He approaches them with a keen, searching intelligence.

"Staggers" found its way onto a number of different recordings, including one by Teddy Charles, whose fingerprints can be found imprinted on this session. Two of the tunes are his, "Kokochee" and "No More Nights."

Mal Waldron had played on (and contributed a tune to) Charles's groundbreaking tentet album for Atlantic, in which Charles experimented with modal forms even before Miles Davis. Phil Woods had a connection of longer standing : both were from Springfield, Massachusetts, and had known each other even before they hit New York. Both had trained at Juilliard. Gene Quill and Woods actually met at a jam session at Charles's loft (there's no record of whether Ezzzard Charles ever showed up there). Hal Stein also played on the Atlantic tentet album.

Tommy Potter had played on some of the Teddy Charles/Wardell Gray sessions. Potter, one of the consummate bebop jazz bassists, was by this time being eclipsed by more assertive and virtuosic bassists, and by the early 60s he had decided to give up music to stay home and raise his family. But he gives this session a solid bebop grounding, as does Louis Hayes, who was starting to make a new kind of jazz with Horace Silver, but was thoroughly grounded in Detroit bebop.

"Kokochee" and "No More Nights" are on the mainstream bebop end of Charles's compositional sspectrum, and they turned out to be a fine couple of tunes for a bunch of alto players. Hal Stein contributed "Kinda Kanonic," and the final tune is a standard by Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh.

The session notes list this as a Prestige All Stars date, but actually the album cover gives the title as Four Altos, and lists the four.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

Mal Waldron had played on (and contributed a tune to) Charles's groundbreaking tentet album for Atlantic, in which Charles experimented with modal forms even before Miles Davis. Phil Woods had a connection of longer standing : both were from Springfield, Massachusetts, and had known each other even before they hit New York. Both had trained at Juilliard. Gene Quill and Woods actually met at a jam session at Charles's loft (there's no record of whether Ezzzard Charles ever showed up there). Hal Stein also played on the Atlantic tentet album.

Tommy Potter had played on some of the Teddy Charles/Wardell Gray sessions. Potter, one of the consummate bebop jazz bassists, was by this time being eclipsed by more assertive and virtuosic bassists, and by the early 60s he had decided to give up music to stay home and raise his family. But he gives this session a solid bebop grounding, as does Louis Hayes, who was starting to make a new kind of jazz with Horace Silver, but was thoroughly grounded in Detroit bebop.

"Kokochee" and "No More Nights" are on the mainstream bebop end of Charles's compositional sspectrum, and they turned out to be a fine couple of tunes for a bunch of alto players. Hal Stein contributed "Kinda Kanonic," and the final tune is a standard by Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh.

The session notes list this as a Prestige All Stars date, but actually the album cover gives the title as Four Altos, and lists the four.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5508595-1395184432-6707.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2151078-1266777872.jpeg.jpg)