LISTEN TO ONE: 'Sokay

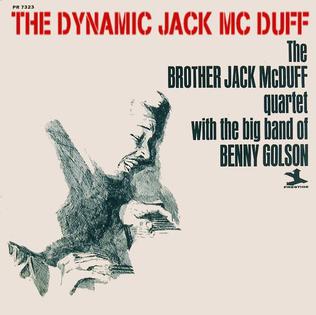

July, 1964. was a busy time in dear old Stockholm. Jack McDuff, now solidly Brother Jack McDuff, was there too, recorded live in Stockholm's Golden Circle with his group, and then in the studio with a Swedish big band. I do wonder if Benny Golson was tempted, after his previous success with McDuff and a big band, to bring the organist and is group into his Stockholm project, but probably not. Golson was looking in a quite different direction. More likely, perhaps, McDuff got the idea of using a Swedish big band from dropping in on his old friend Benny's recording session. More likely yet is the theory that Lew Futterman, McDuff's manager/producer, who had also produced Golson's Stockholm session, was the organizing force behind all of this, and the one who, as before, brought Golson in to arrange the big band session.

LISTEN TO ONE: Au Privave

Soul jazz and the organ combo was still a relatively new sound to Scandinavia--indeed to most of Europe. Jimmy Smith had toured, but European audiences, having graduated from le jazz hot to bebop, were sufficiently skeptical that Futterman had a tough time booking McDuff's tour. As Futterman observes in his liner notes to The Concert McDuff:

Whether or not European jazz audiences, noted for their attraction to the cerebral, would take to McDuff was highly dubious.

But as Futterman goes on to note, at their first stop, the Jazz Festival on the Riviera,

McDuff and his group stole the show. According to Nice Matin, "McDuff a vaincu tout le monde." And in Sweden, the amazed proprietors of Stockholm's famous jazz club, the Golden Circle, saw their audiences dancing in the aisles.

There was enough musical depth in McDuff's music to satisfy the most cerebral of Europeans. And it seemes as though those intellectuals hadn't forgotten how to respond to le jazz hot.

From a historical perspective, it's tempting to focus on the development of young George Benson in McDuff's group, and certainly by the time of this live show at Gyllene Cirkeln (the Golden Circle), he could no longer be considered an apprentice. But while Benson went on to become an international superstar, still regarded to this day as a living legend, and Red Holloway is remembered, if at all, as one of a number of very good tenor saxophonists of the era, it would be a mistake to underestimate Holloway's contribution. His solo on "'Sokay," from the live album, may well be the highlight of that number.

The band that Golson put together for the McDuff/Stockholm studio session is labeled The Big Soul Band, which seems an odd choice for a bunch of Swedes, but it's not out of place. If anyone knew how to arrange a big band to back up Jack McDuff, it was Benny Golson, and the soul is provided by McDuff, Dukes, Benson and Holloway. It's an album very much worth listening to, if you can find it. It doesn't appear to be on Spotify or Amazon Music, and "'Sokay" is the only track I've found on YouTube, which is becoming more and more my source for hard-to-find jazz.

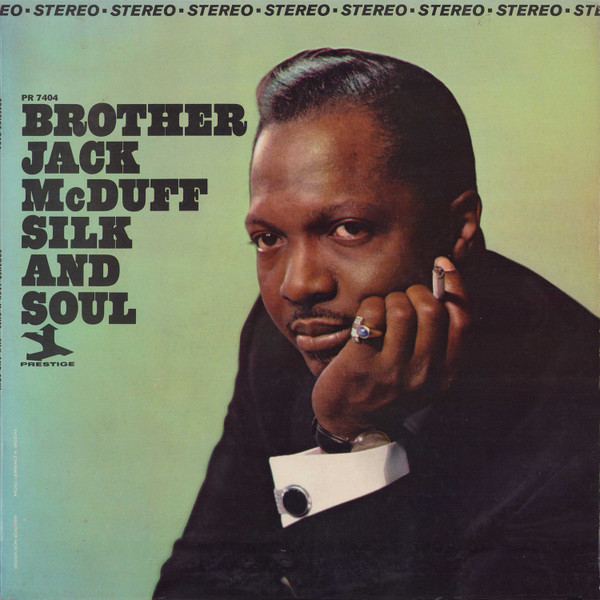

The live album is titled The Brother Jack McDuff Quartet Recorded Live! In Concert Around The World - The Concert McDuff, or more familiarly The Concert McDuff. The Big Soul Band numbers became part of an album called Silk and Soul, which incorporated tunes from two other sessions and was released in 1965. Lew Futterman produced all of the sessions.

July, 1964, was a busy time for Jack McDuff, in and out of Stockholm. During the same month (presumably on his return from Europe, though there are no precise dates for any of these sessions) he was back in New York for a hardworking session during which he recorded nine songs with his basic quartet. all of them in that groove that you can call soul jazz, or funk, or hard bop, or rhythm and blues. Or you can call it by a name that hadn't been invented yet, but which McDuff, Holloway, Benson and Dukes may have pioneered, as several of these cuts would later be collected in an anthology collection called Legends of Acid Jazz.

At the time of their recording, they weren't collected anywhere, exactly. McDuff would make a couple more albums for Prestige before moving over to Atlantic in 1966, so Bob Weinstock's label mixed and matched for a few more releases. "Scufflin'," the first tune off the session, had been added to Silk and Soul. "East of the Sun," "Au Privave" and "Hallelujah Time" made it to Hallelujah Time!, a 1967 album that threw it together with one cut from a 1963 session and a few from a later date. Another bits and pieces album, Midnight Sun, also issued in 1963, contained "Misconstrued," and yet another, 1968's Soul Circle, found room for "Lew's Piece" and Horace Silver's "Opus de Funk." Ray Charles's "I Got a Woman" is the title cut to a 1969 release, and again in 1969, Steppin' Out included "Our Miss Brooks."

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1908660-1556368981-1307.jpeg.jpg)