wrote a couple for Muddy Waters, and Waters and Sunnyland Slim backed him up on some of his early recordings.

Like another songwriter/vocalist, Percy Mayfield, he is mostly remembered for his songs, especially "Goin' Down Slow," a hit for him on the race records charts in 1941 which went on to become one of the most widely recorded of blues standards. It has been recorded by Chicago blues royalty--Little Walter, Howlin' Wolf, James Cotton, and by acoustic folk blues singers like Mance Lipscomb , Sonny Terry/Brownie McGhee, and Memphis Slim. Ray Charles recorded it twice, once in his early West Coast days and once in the 1960s on a blues album for ABC-Paramount. Jazz versions included Jimmy Witherspoon with Ben Webster. Rhythm and blues stars like Little Junior Parker, Bobby "Blue" Bland and B. B. King recorded. Across the Atlantic, it was picked up by Alexis Korner, the Animals, ex-Animal Alan Price, Procol Harum and others. Movie stars have recorded it (Danny Glover). And new versions are still being recorded, most recently by Dee Dee Bridgewater (jazz) and Peter Frampton (rock).

Also like Percy Mayfield, his career had been spiked by a serious auto accident, in 1957. So this, his first album session, was also his first since recuperating from the accident.

Oden's voice had the rawness we associate with Chicago blues, but it also had a bit of a silken quality--again like Percy Mayfield, but still more Chicago raw than West Coast smooth. And he was used to working with the aggressive, take no prisoners style of the best Chicago bluesmen.

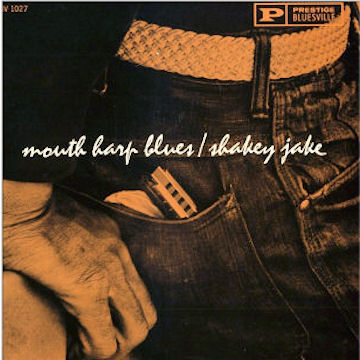

He had one of them on this session--Jimmie Lee Robinson, who had worked the Shakey Jake Harris date for Ozzie Cadena and Prestige just two days earlier. Pianist Robert Banks also comes over from the Shakey Jake session, and plays a much more featured role than he did with Harris. That had been full steam ahead electric guitar and mouth harp blues, this features a more sophisticated

arrangement, built mostly around Banks's piano--similar to the original 1941 version on Bluebird, although Oden's voice has also developed in sophistication over the years.

Listening to Prestige Vol. 2, 1955-56, and Vol. 3, 1957-58 now include, in the Kindle editions, links to all the "Listen to One" selections. All three volumes available from Amazon.

The most interesting book of its kind that I have ever seen. If any of you real jazz lovers want to know about some of the classic records made by some of the legends of jazz, get this book. LOVED IT.

– Terry Gibbs

And Listening to Prestige Vol. 4 is not far off!

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-4618738-1530585718-8243.jpeg.jpg)