McKusick's recording career is mostly bounded by the fifties, although he did appear as a sideman on a few sessions in the early sixties. This album for Prestige was his second to last, and perhaps his most atypical. His music is known for theory and advanced arrangement. He worked closely with George Russell when Russell was developing his Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, an important precursor to the modal jazz of Miles Davis and John Coltrane. Probably more typical of his approach to jazz was the album he made the following year for Decca, featuring five, six and seven-piece ensembles and the work of four very different arrangers: Russell, George Handy, Jimmy Giuffre and Ernie Wilkins, each of whom was asked, McKusick said in a later interview, for "their most advanced thinking."

So how did Bob Weinstock's casual, unrehearsed jam session approach fit with McKusick's talents? Very well indeed, and we're lucky to have this album, and this side of McKusick, just as we're lucky to have the Decca Cross Section--Saxes. Everyone likes to just cut loose and blow every now and then, and the bebop improv approach of head-solo-solo-solo-head, with some casual but intricate duets and dialogs thrown in, can yield some wonderful music, especially with musicians like these.

Billy Byers, like McKusick, came out of the swing era, and worked as a section man in bands featuring the best arrangers. He later would become Quincy Jones's assistant at Mercury Records. So he wasn't exactly the typical Prestige guy either--this was his first session for the label, and he would only do one other, in 1963--but like McKusick, he finds that sweet spot, and the stuff they do together is especially rewarding.

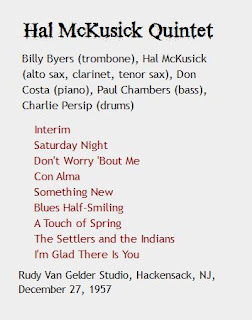

Charlie Persip had done only one previous session for Prestige, but he'd been in the studio on at least one other memorable occasion, as a witness to the strange and thorny afternoon with Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk. He would be back several more times, in the course of a long and distinguished career. Eddie Costa was also making his second appearance on Prestige. The first had been on the vibes, accompanying Bobby Jaspar and Tommy Flanagan. He looked to be at the dawn of a major career. In 1957, he would be named Down Beat's new star on both piano and vibes, the first time a musician had gained that honor on two different instruments. But an auto accident would take his life a few years later.

Paul Chambers was, by this time, one of Prestige's stars, and with good reason. His solos, both plucked and bowed (on "The Settlers and the Indians") are musical gems, and that's not by chance. Chambers, as we know, hit New York as a 19-year-old wunderkind, already a master of his instrument. After all, he had started in the jazz cauldron of Detroit, where musicians matured early. His friend, drummer Hindal Butts, remembers (again from Lars Bjorn and Jim Gallert's indispensable Before Motown: A History of Jazz in Detroit 1920-1960):

Paul was determined to make the bass a solo instrument and he practiced, hour upon hour. I waited on Paul to take a couple of girls out, and he wouldn't stop practicing! He loved to bow and he mastered the bow.Butts was a member of a quartet led by Kenny Burrell and Chambers, called the Four Sharps. And, given that this is the early 50s, that would almost sound like a doo-wop group, wouldn't it?

Well, yeah. This was Detroit, where music was music. The group played modern jazz, and they also sang four-part harmonies. We can't exactly know how good the Four Sharps (who also, at various times, included Tommy Flanagan, Frank Foster, Yusef Lateef and Pepper Adams) were as a vocal group, because no records of their music have survived, but we sort of can. Again, from Hindal Butts:

We recorded "The Nearness of You" ... Kenny sang the lead, we sang the backup and we did the bridge in unison ... Kenny called me one day and said, "Turn the radio on." He was mad ... I turned the radio on and the Four Freshmen were singing [our arrangement of] "The Nearness of You" almost note for note.Butts recalled that the Four Freshmen, when they were playing Detroit, used to stop in at Klein's Show Bar when the Sharps were playing there, and request the number over and over.

McKusick composed three of the tunes for this session. He turned to some top composers for a couple of others: Dizzy Gillespie's much-recorded "Con Alma" and Jimmy Dorsey's "I'm Glad There is You."

And some more surprising choices. "The Settlers and the Indians" was written by Bobby Scott, who was, at just about the same time, climbing the Top Forty charts with a rock 'n roll song called "Chain Gang." He would later write "He Ain't Heavy, He's My Brother" for British rockers The Hollies, and win a Grammy for "A Taste of Honey." Incidentally, I've lauded Wikipedia for their excellent entries on jazz albums, but that doesn't mean you can count on the Internet across the board. There are a whole bunch of sites devoted to lyrics, and I don't know who's ripping off who, but if there's a mistake in one, the same mistake will be in all of them. Take, for instance, the lyrics to "The Settlers and the Indians." Every one of these sites features lyrics to "The Settlers and the Indians," and every one of gives what are actually the lyrics to "Don't Worry 'bout Me." Maybe someone was listening to this album, because McKusick also does "Don't Worry 'bout Me," a song by Rube Bloom and Ted Koehler that's a standard for jazz vocalists, my favorite version being King Pleasure's.

"Something New" is credited to Albert Gamse and Ricardo Lopez Mendes, both of whom were lyricists, but someone must have chipped in a melody. And "Saturday Night" is the really interesting one. It was the title song for a musical with a book by Julius and Philip Epstein, who had co-written the screenplay for Casablanca, and had turned the composer job over to an unknown, who remained unknown, as Saturday Night never made it to Broadway, and lord knows where McKusick found it, especially since the young unknown was being told at that point to stick to lyrics, because his melodies weren't quite good enough. And in fact, while McKusick was recording "Saturday Night," Steven Sondheim's lyrics were making their mark on Broadway to Leonard Bernstein's music for West Side Story.

The album was called Triple Exposure. McKusick's "Interim" and "Don't Worry 'bout Me" didn't make the cut, but were later included in the New Jazz compilation album, Bird Feathers.

McKusick lived a long and productive life, dying in 2012 at the age of 87. He composed music for two plays by his friend Edward Albee, "The Sandbox" and "The Death of Bessie Smith." He taught for a number of years at the exclusive Ross School on Long Island, where he moved in the early 1970s. Of his years on the jazz scene of the 1950s, he said this, in an interview with the AllAboutJazz website. He was talking about Cross Section--Saxes, but he could have been talking about Triple Exposure, or indeed, any album by any of the New York jazz musicians:

The sound was a reflection of our lives in New York--the intensity, the art, the optimism all squeezed together.

Order Listening to Prestige, Vol. 1 here.