chose a young man whose career had just begun but who already had the promise of stardom--a promise on which he would richly deliver, though mostly not for Prestige.

Grant Green was 25 when this album was made. His earliest musical models were saxophonists -- Charlie Parker, Lester Young -- along with the seminal jazz guitarist Charlie Christian; as a result, he favored a single-string approach to playing. A St. Louis native, he started playing in that city with Jimmy Forrest. Lou Donaldson discovered him there, brought him to New York, and introduced him to Alfred Lion, who immediately set him up to record as a leader with Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones. The album went on the shelf, not to be released until the new millenium, but Green stayed with Blue Note, where he would quickly achieve stardom. He had made his second Blue Note album (guitar, organ, drums) just the week before this Prestige session. It would become Grant's First Stand, his first album released, and he would cut five more before the year was out.

McDuff and Forrest are the central figures for this session, but Green and Ben Dixon contribute too. Dixon had recorded once before for Prestige, on the 1957 Ray Draper album that marked the debut of trumpeter Webster Young. Young and Dixon had moved to New York from South Carolina together, and Young insisted that Dixon be included on the gig. Perhaps much the same thing happened here, since he had played with Green the week before on the Grant's First Session album. He would continue to work with Green throughout the 1960s.

We are starting to hear, more and more, the development of the soul jazz sound, and we're learning a couple of things. First, it really is a new sound. It comes from bebop and hard bop and rhythm and blues, but it's not any of them. And although it would, in time, wear out its welcome and its capacity for originality, that certainly had not happened yet in 1961. And although everyone wanted that organ sound for their soul jazz recordings, that wasn't falling into a rut, either. A lot of very talented musicians were playing soul organ, and each was carving out her or his own stylistic niche.

McDuff also draws his music from some interesting sources. Three of the tunes on the album ("Dink's Blues" (a traditional blues here credited to McDuff), "Blues and Tonic," "Whap!") are McDuff originals. Of the other three:

- Henry Mancini was becoming one of the hottest composers around, having brought jazz to network TV with Peter Gunn. His theme for another TV show featuring a suave crime-solver, Mr. Lucky, never quite achieved the ubiquity of the Peter Gunn theme, but it was Mancini, and it got its share of interpretations, from the Dixieland of Jimmy and Marian McPartland, to the Latin rhythms of Jack Costanzo (mambo) and Laurindo Almeida and Mancini himself (Mr. Lucky Goes Latin), to the hard bop of Donald Byrd and Pepper Adams (with a young Herbie Hancock). It fits nicely into the soul jazz idiom too, though with the typical organ combo lineup of no bass it's hard to exactly duplicate the Mancini walking bass.

- "The Honeydripper" was written and performed by rhythm and blues pioneer Joe Liggins. It was a huge hit for him on the race charts in 1945-46, and it spawned a number of first-rate covers, mostly by blues and rhythm and blues artists. Not so much in the jazz field, although you'd think it would have been a natural for soul jazz artists. But Cab Calloway did record it in 1946, and Oscar Peterson in 1963. On this one, McDuff really does carry the walking bass part on his organ.

- "I Want a Little Girl" was first recorded in 1930 by McKinney's Cotton Pickers. It was written by Murray Mencher and Billy Moll, two gentlemen with whom you really would not associate the authorship of a blues standard. Mencher is best known for "Merrily We Roll Along," the theme music for the Merrie Melodies cartoons, and Moll for "I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream for Ice Cream." The song lay dormant for a decade, had a couple of covers in the 1940s, including one by Jay McShann. In 1955 it was picked up as "I Want a Little Boy" by Kay Starr, a big band singer trying her best to stay relevant in the rock and roll era. That wouldn't seem to be an auspicious comeback for a song with ambitions to be a blues classic, but then in 1956 and 1957 it was recorded by two of Atlantic's greatest blues singers, Joe Turner and Ray Charles, and those gave it thoroughly hip credentials. McDuff's was actually not the first jazz organ version of the tune: rhythm and blues bandleader Doc Bagby had done it in 1955. McDuff, Forrest, Green and Dixon do a great rendition, probably my favorite cut on the album.

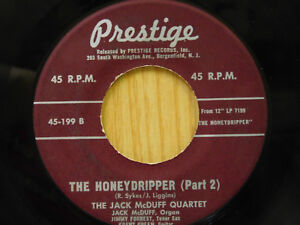

Esmond Edwards produced. The Honeydripper was the title of the album, and given how huge a hit the title song had once been on 78 RPM, it was chosen as a two-sided 45 RPM single.

1 comment:

Sweet....and Rudy's new stdio only about 2 years olde

Post a Comment